William Hogarth’s The March to Finchley 1750–61 (Tate T01802) depicts a drunken and chaotic tumult on Tottenham Court Road in London, a mustering of troops so disorderly that they hardly seem able to make it to the end of the road let alone Finchley where they are expected to defend the capital against an imminent Jacobite rebellion (fig.1). While the disorder represented by Hogarth is not quite in the same league as the uniformed soldiers of Regency France whom the philosopher Michel Foucault described as ‘the army, that vagabond mass’, what the picture captures is the protean British Army in flux, before extreme training and body regimes and before the mass building of barracks, which removed soldiers from the apparent contagion of social discontent and a burgeoning revolutionary sensibility.1 This is an army of ill-disciplined men, with all their faults and ribaldry, before their transformation into the enlightenment model of a modernised clockwork army, a body-machine complex.2

William Hogarth, Luke Sullivan

The March to Finchley (1750–61)

Tate

In contrast to the work of Hogarth and his contemporaries, twenty-first-century artists find it a lot harder to critically represent the armed services, their activities and habitat. Bypassing war-zone reportage and the institutionally sanctioned role of the war artist, this paper focuses on those places in the domestic landscape where war is continuously simulated and prepared for but which remain invisible to the public. It looks beyond romanticised and nostalgic representations of military activity, beyond propaganda and nationalistic forms of art to identify artworks that investigate the spaces and vestiges of modern military activity. In so doing it also points to why art practice is a valid and productive tool for studying military activities and the evolving spaces of militarism.

The lack of artistic engagement with the activities of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) is perhaps principally due to the relative segregation of defence personnel, land and airspace from the civil domain. Unlike Hogarth’s era, when troops were generally billeted among the civil population and trained on common land or private estates (and hence highly visible in the landscape and urban centres), today’s MoD has its own vast training estate with numerous barracks and an enormous stock of housing, all of which are detached from public scrutiny. The public are prevented from accessing many areas of the defence estate for two reasons: the extreme danger of live weapons and hazardous activities (and related issues of potential litigation), and the restrictions on privileged, strategic or commercial information in the interests of national security. The MoD is generally keen to disseminate information to the general public where possible. However, it is typically the most sensitive or dangerous activities and spaces that are the most compelling for researchers. Many of the artists discussed in this essay approach their subject from a position of criticality, using their work as an investigative tool with which to extract privileged and once secret knowledge from the landscape and re-present it as cultural artefact. What becomes clear is the degree to which artistic production in this area not only involves a significant amount of preparatory research – indeed, in many cases the art and research are indivisible – but that it also requires a great deal of ingenuity to gain access to people and places and, occasionally, the application of barely-legal methods of circumventing security protocol.

The artistic research charted in this essay can be said to follow three thematic trajectories. The first critically reflects on the past, ruminates on the ruination of military structures in the landscape and uses artistic methodologies to examine the technologies of militarism and mass destruction. The second reflects on how landscape is interpreted by certain technologies as an extension of the military imagination by visualising this shift in the ‘logistics of perception’.3 And the third and final strand of research employs investigative and relational strategies to create work that directly reveals clandestine information and speculates on the institutional frameworks that restrict the dissemination of knowledge.

When the writer W.G. Sebald visited an isolated shingle spit on the Suffolk coast in August 1992 he was doggedly pursuing, despite his own fatigue and trepidation, the spectre of human annihilation.4 At Orford Ness he encountered the architecture of weapons testing and, most notably, the temple ‘pagodas’ of atomic research which are easily the most distinct features on the spit, projecting from the low dunes like Brutalist follies. From this point Orford Ness became emblematic of a secret Cold War landscape that still shocks or intrigues but has, ironically, become exposed in a way that other parts of the defence estate have not.

During the Cold War many military sites were defined by their acute difference and detachment from civil space: they were highly secure, wilfully secretive and in many cases controlled by a foreign power (principally the USA). The presence of nuclear weapons (or even an association with such weapons) invested many of these spaces with an apocalyptic charge: the triple-fenced perimeters and the ‘sterile’ zones around the hardened bunkers all spoke of difference, exclusion and ultimately the absence of life on earth. Freud’s death drive, in its most sophisticated form, haunted the site, which was presided over by an impenetrable shell of political illogic. These hermetic spaces, with their incumbent national framework of early warning systems, their partial sub-surface invisibility and cult-like detachment, could undoubtedly be considered parallel to civil society and, in fact, parallel to life itself. These are spaces which, to borrow from Sebald, ‘cast the shadow of their own destruction before them’.5 Any serious study of the Cold War military landscape (including those immense underground bunkers that prefigured the spectacle of mass premature burial) would be one not of war but of eschatology.

Drawing on extensive research on Cold War architecture and technology, the artist Louise K. Wilson undertook a series of performances and artworks, collectively known as A Record of Fear, at Orford Ness in 2005. The decommissioned and decaying Atomic Weapons Research Establishment laboratories provided the subject and the venue for a number of sound works. In Lab 2, a building semi-submerged under a drift of shingle and which once housed an enormous centrifuge used for environmentally testing free-fall nuclear weapon casings, Wilson installed two large infra-bass sub-woofer speakers. She also managed to gain access to AWE Aldermaston in Berkshire and recorded the sound of the same centrifuge used in Lab 2 during tests (which had been relocated to Aldermaston after the closure of Orford Ness). Played back in the cylindrical central room, the throbbing, cycling, cardiac pulse of the weapon as it reaches one hundred revolutions per minute is ‘the sound of a machine simultaneously present and absent; an echo of the past that is incontrovertibly present’.6 The auditory possibilities of this isolated and otherwise uncommunicative military complex were pushed further when Wilson persuaded a chamber choir, the Exmoor Singers, to perform at the site. In the control room adjacent to the ‘pagoda’ laboratories, the singers gathered funereally around the casing of a WE177A free-fall nuclear bomb still on its loading trolley, and sang John Ward’s Elizabethan madrigal of unrequited love Come Sable Night ‘transformed into a lament for an age of pre-nuclear innocence’.7 In another cylindrical centrifuge laboratory, the singers arranged themselves in a coaxial circle and performed John Bennet’s madrigal Weep, O Mine Eyes (fig.2). James Jarvis, the company’s Musical Director later remarked, ‘The sheer volume of sound that could be driven within this resonator by a few voices was overwhelming; the harmonic possibilities of the common chords could be exploited to the nth degree; and the dissonant suspensions had a searing effect’. Although Wilson extracts sounds from the white heat of atomic research and deploys highly emotive music within the sunken chambers of Orford Ness, the effect of these interventions is not combative or antagonistic but generous and conciliatory, perhaps the only response, in the words of Sebald, to ‘being on ground intended for purposes transcending the profane’.8

Fig.2

Louise K. Wilson

Weep, O Mine Eyes 2005

Still from video

© Louise K.Wilson

For their four-screen video installation Gamma 1999 (Tate T07698, fig.3), Jane and Louise Wilson filmed at RAF Greenham Common in Berkshire, a site once infamous for housing ninety-six tactical Ground Launched Cruise Missiles (GLCM) and being the object of a sustained non-violent campaign by the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp.9 Although the title of the work seems like a misspelling of the acronym attributed to the distinctive hardened shelters built to house the missiles – GLCM Alert and Maintenance Area (GAMA) – Gamma refers instead to the type of lethal ionised radiation that emanates from a nuclear detonation.10 It is unlikely that the GAMA compound would have been visible from outside the perimeter of the base, but from the airfield it shares with many Cold War sites in the UK (including those at Orford Ness) a baleful, tumulus-like appearance, resembling a tumour barely concealed under the surface of the land.

Fig.3

Jane and Louise Wilson

Installation view of Gamma 1999

Video on four screens

Purchased with Funds provided by Edwin C. Cohen 2001

Tate

Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York

Invoking the internalised anxieties of the Cold War, the camera in Gamma drifts and lurches around control centres, corridors and offices, from one confined space to the next in this once highly restricted facility, and offers fractured glimpses of female uniformed personnel (the artists themselves) pacing the floors like automatons. While Jane and Louise Wilson rummage inside the belly of the beast, dwelling on the architecture of cruise missile delivery systems and revel in the minutiae of outmoded military technology, the filmmaker Patrick Keiller’s cinematic release Robinson in Ruins (2010), with its unflinching, static gaze, stares GAMA full in the face.11

RAF Greenham Common is in fact one of a number of ‘ruins’ and sites of contested ownership that are invoked by Keiller to illustrate the historical and contemporary enclosure and subtraction of land from common use and, ultimately, the crises of economic and environmental collapse (fig.4). A parallel can easily be drawn between the peace protests at the military base (specifically the linking of hands around its perimeter by 30,000 women in 1982) and another site of protest mentioned later in the film, when 1,000 people walked the circumference of Otmoor, Oxfordshire in 1830, tearing down fences and hedgerows as they went, and ‘possessioning it’ after common grazing and farming rights were revoked by the landowners.

Fig.4

Patrick Keiller

Still from Robinson in Ruins 2010

Film

Courtesy Patrick Keiller

Robinson in Ruins is the third film by Keiller in a trilogy of fictional travelogues, each of which are peppered with military sites. RAF Brize Norton, the Atomic Weapons Establishment at Aldermaston, RAF Greenham Common, Government Pipeline and Storage System (GPSS) sites, to name a few, are all militarised environments and infrastructures that can be read as examples of a sustained military land grab in the twentieth century – another wave of enclosure that amounts to over 371,000 hectares of the British landmass reserved for training and defence.12 While this issue is not the principal focus of Keiller’s films, what can be learnt from his extensively researched body of work is that there is a pronounced military presence in the British landscape: it is there in the militarism of rusty barbed wire fences and padlocked gates, decaying or re-purposed Second World War airfields, jerry-built pill boxes, abandoned rocket facilities and sinister Cold War sites. Occasionally the buildings are brutal and iconic: giant hangers hide enormous transporter aircraft and conspicuous fungoid radomes house spinning radars or secret eavesdropping devices. While structures of this kind do disrupt certain expectations of the British landscape, it is also true that many of these places are being protected as heritage sites and welcomed into the somewhat arbitrary register of historically significant architecture.13 However antiquated, dilapidated or parochial the defence estate may seem in some quarters, Keiller’s films serve as reminders that the British military continues to be connected to a globalised military network animated by conflicting defence policies and dubious arms sales, not to mention contentious warfare.

The complex military infrastructure of the UK, which is so easily overlooked in the landscape (or only studied after elements of it fall into obsolescence), is in fact almost constantly engaged in warfare. In Northern Ireland, for example, the imposition of direct rule from Westminster, beginning in 1972 and continuing sporadically until 2007, resulted in the persistent presence of the British Army in the region. Jonathan Olley’s remarkable series of photographs, Castles of Ulster (1997–2000), show police stations and British Army barracks refortified with corrugated steel (in the event of sporadic attacks by barrack-buster mortars) and bristling with improvised defences, their elevated watchtowers scrutinising communities below with obvious menace (fig.5).14

Fig.5

Jonathan Olley

Golf Five Zero Watchtower. Crossmaglen, South Armagh, Northern Ireland, UK 1998

Photograph

© Jonathan Olley

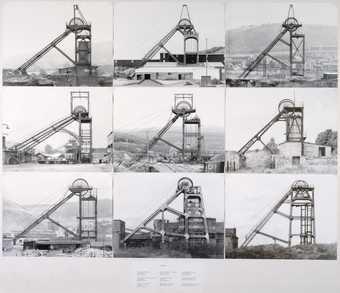

Olley’s photographs offer a typology of deeply sinister utilitarian structures, each one a hastily assembled bricolage of steel mesh, concrete, surveillance cameras and communication antennae. In the context of bitter sectarianism, street fighting and long-nurtured antagonism, these ‘supersangers’, watch towers and barracks inhabited strategic and elevated positions – the motte-and-bailey castles of modern urban occupation. The monochromatic, formal bias of the series also clearly emphasises the way that the architecture of urban conflict morphs rapidly, accelerating the process of evolution ascribed by the photographer Bernd Becher to industrial buildings that are ‘constantly updated and upgraded with pipe systems’ and that ‘goes through stages like an insect’.15 Olley’s work reveals the military to be an adaptive creature-machine that exists for the purpose of social and territorial control.

The writer Brian Dillon suggests that artists such as Jane and Louise Wilson and Tacita Dean have ‘courted a kind of military-industrial sublime’, a ‘re-animation (or maybe an occult conjuring) of the corpse of Modernism’.16 This tendency may also be true of Louise K. Wilson’s work at Orford Ness and even of Gair Dunlop’s twin-screened short film Atom Town: Life After Technology 2011, set in the Dounreay Atomic Research Establishment site. The film draws on archive footage, original television broadcasts, training and educational films, and interviews with employees – all shown in parallel with Dunlop’s own footage of the site. Atom Town presents a place seemingly abandoned and stripped of human life, but simultaneously recalls an era when nuclear technology was akin to alchemy in the public imagination. As the writer Ken Hollings remarks in the film’s publicity material: ‘Both [Cold War technology and atomic science] represent hermetically controlled operations that subtly and radically transform nature, thereby unleashing occult powers that remain hidden in all but their effect, whether socially, culturally or materially.’17

While there may be a degree of ruin lust in these works, their approach to historical events could be described as a ‘current problem facing our present existence’.18 After all, nuclear weapons are still very much with us, and Dounreay is one of nineteen nuclear energy and research sites in the UK that face decommissioning with a highly problematic legacy of radioactive waste stretching into the distant future.

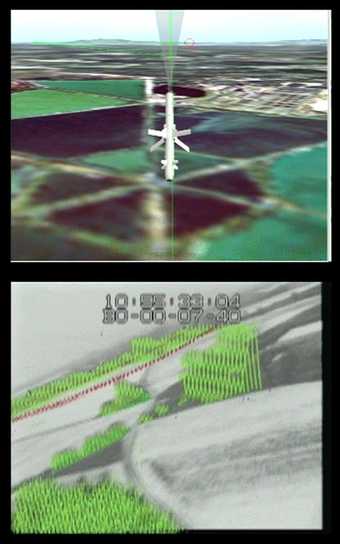

The utilitarian characteristics of military architecture, whether evident in the shingle coastlines of Suffolk, the heath lands of Berkshire or the urban centres of Northern Ireland, follow the logic of defence, science and warfare. That logic, in turn, extends and orders the landscape and environments around it, ‘to support claims to territory, to define places as legitimate places for soldiering, to prioritise particular land uses over others’.19 This claim holds good for the domestic ‘home’ defence estate as it does for wars and combat zones. In her book Military Geographies, the writer Rachel Woodward explains how a military perception of the landscape becomes rationalised as ‘terrain analysis’ and features of the landscape are interpreted in terms of manoeuvres, strategies and tactics, where the ‘reading of the landscape is a rationalistic one, possibly even a masculine one where seeing and knowing are conflated’.20 In this schema the landscape is broken down into symbolic components: objects with discernable values, as threats, potential threats or for their defensive potential. Superfluous content is ignored or denied. Landscapes are also ‘read’ in a similar manner by semi-autonomous weapons systems such as BAE’s Sampson radar which, during recent trials, was able to ‘track and plot a firing solution for every aircraft arriving or leaving from Heathrow, Charles de Gaulle, Schipol and Frankfurt airports’.21 This ‘passive’ targeting mirrors the somewhat more aggressive tactics used by low-flying RAF jets, habitually selecting cars and houses as mock ‘targets’ across the highlands of Scotland.22 Harun Farocki’s chilling Eye-Machine I–III (2001–3) cycle of video installations demonstrates how autonomous vision operates within emerging technologies and weapon systems. Eye-Machine III, for example, is a montage of moving images structured around what Farocki has termed the ‘operational image’, the image as process rather than the portrayal of a process (fig.6). The video illustrates how cruise missiles used a stored image of a real landscape then took an actual image during flight, [and] the software compared the two images:

A comparison between idea and reality, a confrontation between pure war and the impurity of the actual. This confrontation is also a montage and montage is always about similarity and difference. Many operational images show coloured guidance lines, intended to portray the work of recognition. The lines tell us emphatically what is all important in these images, and just as emphatically what is of no importance at all. Superfluous reality is denied – a constant denial provoking opposition.23

Fig.6

Harun Farocki

Two stills from Eye/Machine III 2003

Single-channel video

© Harun Farocki

It is worth mentioning that the Gryphon Ground Launched Cruise Missiles stored at RAF Greenham Common employed the same Terrain Contour Matching (TERCOM) technology, a standard feature of Tomahawk-based systems developed during the 1970s. This connection also draws together the work of Keiller and Farocki, two politically engaged film essayists whose individual approaches to their subjects demand long periods of research.

Because privileged information relating to military geographies and activities in the UK is restricted, investigatory research by artists and others is generally limited to information already in the public domain or sanctioned as a request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The American artist and geographer Trevor Paglen, who takes photographs of military activities, remarks that:

While there is this vast architecture, this vast secret state, there is basically no statutory basis for secrecy in the United States … What that means is that [secrecy laws] just apply to the executive branch. That doesn’t apply to people who aren’t part of it. It is very different in a lot of other countries. In the UK, if you did this kind of work you could be prosecuted as a civilian for releasing some of this information.24

The Official Secrets Act applies to all citizens of the UK whether they have ‘signed’ it in an official capacity or not. The Act is usually deployed in cases of suspected espionage, and there is no public-interest defence. If Paglen were to make work in the UK, his practice of ‘Limit Telephotography’ might also cause to be invoked the Terrorism Act 2006 and the Counter Terrorism Act 2008, which both come down heavily on an individual or institution who publishes or communicates ‘a photograph of a constable, a member of the armed forces, or a member of the security services, which is of a kind likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism’.25 Among many investigative techniques, Paglen uses cameras with extreme telephoto lenses (with focal length ranges between 1300 mm and 7000 mm) at distances of up to forty miles to capture images of active weapons testing sites and workers boarding unmarked jets to secret bases.26 Photographs such as Chemical and Biological Weapons Proving Ground, Dugway, UT/Distance ~ 22 miles/11:17 am 2006 or Control Tower/Cactus Flat, NV/11:55 am/Distance ~ 20 miles 2005 reveal the technical impossibility of adequately recording images of such sites through miles of atmospheric pollutants and heat haze, even with the most sophisticated optical apparatus. In doing so, however, they also pose a paradox about vision and the limits of knowledge: in attempting to expose dubious military practices and bring clarity to the landscapes of secrecy, Paglen produces tantalising abstractions, horizontal smears of desert gold or shimmering mirages (fig.7). The images hint at the possibility that the subjects themselves may well only be distortions of the light, and that viewers, thirsty for disclosure and accountability, are actually in danger of creating their own myths.

Fig.7

Trevor Paglen

Chemical and Biological Weapons Proving Ground/Dugway, UT/Distance ~22 miles/11:17 am 2006

Photograph

© Trevor Paglen

Compared to the vast and isolated militarised landscapes of the USA, restricted sites in the British countryside are a lot more difficult to hide. The MoD’s weapons testing and evaluation centre at Shoeburyness on Foulness island, for example, is only six miles from the nearest large town, Southend-on-Sea, and twenty miles from outer London.27 Similarly, the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) at Porton Down, and the nearby Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear events (CBRN) Centre at Winterbourne Gunner are responsible for undertaking some of the most sensitive and secretive activities commissioned by the British Government and are both close to numerous Wiltshire villages and towns. It is possible, in fact, to drive up to the front gates of many such places, which is exactly what the London-based Office of Experiments (OOE) does for part of its Overt Research Projects.28 Sharing similar tactics and modes of practice with the Centre for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI) based in the USA, the OOE gathers and disseminates information about marginal and secret geographies, contentious issues of land use and illegal government activities, and organises guided bus tours to active and decommissioned military sites around the UK. The OOE has developed a strategy of enquiry akin to an archaeology of secret and privileged knowledge, inhabiting a highly productive grey area between artistic production and information archiving that involves compiling databases, commissioning artworks, organising exhibitions and collaborating with other organisations and individuals (including the CLUI).29 In fact, the founder of the OOE, Neal White has stated that because of the unequal power relations between artists and government, scientific and military institutions, it was necessary to construct ‘counter-institutions’ to redress the balance of power.30 In this respect, the OOE is as much a critique of the instruments of powers and the ways in which they may function as it is a gatherer of information and a producer of art.31 White states that one of the aims of the OOE is to bring artistic researchers and political activists in from the cold and legitimise their activities within a counter-institutional framework. When an OOE tour bus filled with researchers stops outside Porton Down defence laboratories, its purpose may be part-performative spectacle and part-legitimate research, but it also serves to illustrate how strategies of art and activism are mutating and finding new ways to push at the borders of secrecy and power.

What many of the artworks in this paper describe is the military unconcealed in the landscape, prised open, exposed, deconsecrated. With either an intoxicated fascination for the dark imminence of destructive potential in the British landscape, or as a way of strategically presenting alternative platforms for research, activism and protest, these works push against invisible forces and boundaries, and employ original techniques to visualise or represent things that have been necessarily and deliberately hidden.