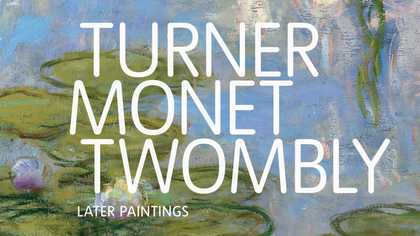

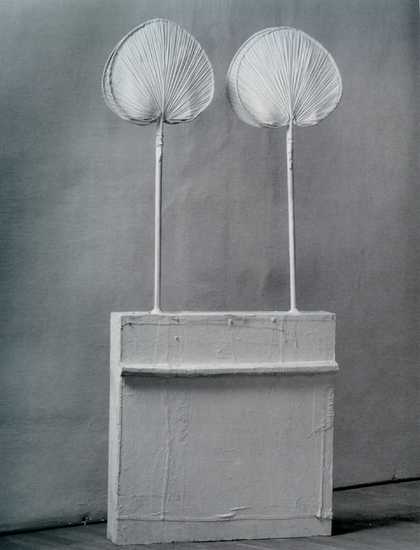

Fig.1

Cy Twombly

Untitled (Funerary Box for a Lime Green Python) 1954

Photo: Cy Twombly © The artist

Cy Twombly’s Untitled (Funerary Box for a Lime Green Python) 1954, stands fifty-five inches tall, roughly torso-height if viewed in person (fig.1).1 It comprises four palm leaves dried and edged to form fans; wire that attaches these fans two at a time to attenuated ‘stems’,2 and a shallow, upended wooden box that one imagines elsewhere useful for horizontal storage. The entire assemblage is coated with white house paint, as if to neutralise the heterogeneous effects of its diverse objects and, by quieting their local colours, to make all the more legible the individual aspects of each found object in relation to one another. Some patched lengths of fine white cloth have been affixed across the front and narrow sides of the box after painting, nuanced by seams and puckers like a tablecloth here rendered vertical, one kind of material whiteness covering another.

For decades Twombly’s sculptures have been found-object constructions, assemblages of studio or other everyday materials overpainted with varied slips or washes of white. From the late 1950s some sculptures have been painted additionally with other pigments, often reds or blues, and some are drawn and written across in graphite, paint, and crayon. Twombly has spoken about the whiteness of his two-dimensional work in terms of the draughtsman’s or writer’s empty page.3 In discussion of his three-dimensional work, however, he has called white paint his ‘marble’.4 White paint for Twombly is always intelligible as the dripping, smearing, tangible stuff that is paint, but it is also available for him, and for us, as writer’s paper and sculptor’s marble. White paint here, among other things, permits an at-once-ness of literal and allusive materiality. So, too, with the other literal materials of Twombly’s sculptures, the boxes and fans and wire: they are always themselves, readable as such, and they are always engaged in opening, if never transcending, their materiality.

Already I have used words like readable, legible, literal, intelligible, though it should be added at the start that, while Twombly’s sculptures are all of those things, they are also difficult, obdurate, not blank yet often silent, even recalcitrant, in their painted whiteness. This difficulty tends to intrigue, or at least to mystify, rather than to stymie. We can see the sculptures for all of their parts, for every touch of material, but the way that these parts and materials make meaning sculpturally remains the nagging question – not necessarily the right question, only the nagging one.

I begin with an object because I hope never to feel too far, in this paper, from the physical object. But my essay’s larger concern is with the relationship between words and objects, as well as with words for objects, in Twombly’s sculptural practice. Still more crucially, Twombly’s sculptures provide us ways to think about words apart from the two-dimensional realm of the page and in relation, instead, to the three-dimensional realm of the object or thing. They require careful, if sometimes uneasy, distinction between the words sculpture, object, and thing. At the same time, they tempt such labels, categorisations, and discourses without satisfying any – or, perhaps, by satisfying too many at once. Sculpture is a contested word in twentieth-century art history, especially after World War II – multiplicitous in meaning, expanded, and sometimes disbanded entirely. Neither are the vagaries of a word as handy yet unspecific as thing any less fruitful for us. Meanwhile, Twombly has had lifelong recourse to literary sources, most often poetic ones, across his numerous modes of visual work, and in much of the critical literature the artist is himself named a ‘poet’ far more often than a ‘sculptor’, or even a ‘painter-sculptor’. The very word poet that derives from the Greek for a ‘maker of things’ – that is, things verbal, sculptural, or otherwise.

Our focus here will remain with the 1954 sculpture, and therefore with Twombly’s early years of such production, though this focus is maintained in the interest of gauging the consistencies of Twombly’s sculptural practice to the present day. The piece in question is one of twenty-two published in the Catalogue Raisonné between the first documented construction in 1946 and a seventeen-year sculptural hiatus that commenced in 1959. It is also the only one of Twombly’s sculptures from that initial campaign to have a name.5

This name – Untitled (Funerary Box for a Lime Green Python) – has changed over time, possibly given to the piece later than 1954, although in the 1994 Twombly retrospective held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York the sculpture was returned to a wholly untitled state. Curator Katharina Schmidt explained in her 2000 Basel exhibition catalogue that Twombly had grown unhappy with the title’s parenthetical extension: its python in fact a misnomer, for what Twombly had meant was a cobra, the shape of whose head would be in keeping with the pair of palm leaves that face us here.6 For Tate Modern’s 2008 exhibition, as for the 1997 Catalogue Raisonné, the full title, python and all, has been pleasingly renewed.7

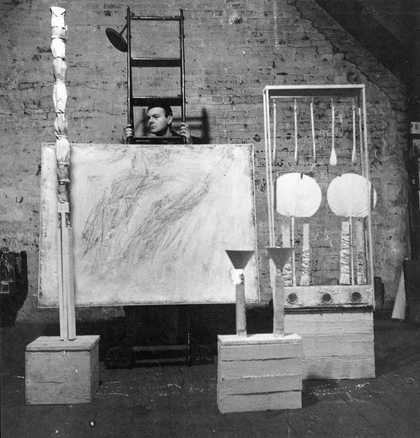

Material changes likewise affected this sculpture in its first years. It and others were photographed in 1954 at Robert Rauschenberg’s studio in Fulton Street, New York, which Twombly briefly shared.

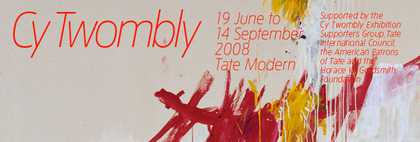

Fig.2

Robert Rauschenberg

Cy Twombly with Artworks at Fulton Street 1954

Rauschenberg Archive © DACS, London/VAGA, New York

In one of these photographs (fig.2) we see a different double-palm sculpture prominently posed, this one no longer extant (the majority of the sculptures in the 1954 photographs have been lost or destroyed). In another (fig.3) we find our double-palm piece, surmounted by an open box frame from the top of which dangle five wooden spoons. Four bundled and twined uprights flank the palm leaves, and three round mirrors are ranged across the top of the box support. The current version of this sculpture, of course, retains only that box support, the palm fans, and a wooden ridge that was once the lower front span of the original overarching frame. This strip of wood now functions as purely formal horizontal emphasis, as if to provide, in parallel with the box’s top edge, a doubled horizon line to counter the doubled vertical of the fans.8

Fig.3

Robert Rauschenberg

Cy Twombly with Artworks at Fulton Street 1954

Rauschenberg Archive © DACS, London/VAGA, New York

Confirmation of the date and reason for these alterations is difficult to secure. Twombly has indicated that the original dangling spoons from the Funerary Box sculpture were removed and redeployed as the rounded vertical sticks (spliced among a flat, frontal bundle of otherwise squared ones) of a fifteen-inch ‘panpipe’ sculpture – though that piece is dated 1953, one year before the Funerary Box piece itself.9 In 2001 Achim Hochdörfer affirmed that the sculpture’s decisive paring down did occur early on, but that the layer of cloth and further coats of paint were added to the piece’s lower half decades later, in preparation for the first, small exhibition devoted to Twombly’s sculptures, held in Naples in 1979; whether by way of repair, reinspiration, or reinvention we do not know.10 Whenever and however the changes were manifested, they were drastic, an eradication of both decorative detail and encompassing frame, and signalling, too, a radical shift in tone from ornamented to spare. On the other hand, these changes served to strip the original structure down to a kind of essential core: our eyes rise from a grounded square form to one horizontal, then two vertical, lines, and finally to the paired, moon-like near-circles. It is like a sentence now devoid of extraneous words, except for the wooden strip, that horizontal remnant which yet productively mediates between box and palm stems, between original and final product.

In current literature on both mid-century and contemporary assemblage sculpture, the freshly resuscitated term of interest seems to be bricolage, employed by anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss in his 1962 The Savage Mind as the kind of tinkering, contingent piece-work particular to the ‘mythical thought’ of non-Western cultures, a way of dealing with, and of making from, the leftovers of human endeavours.11 When pressed in a 1959 interview with Georges Charbonnier on the relationship between practices of bricolage and practices of Western art-making, Lévi-Strauss proved reluctant but did at last tellingly conflate the behaviours of words with those of objects: ‘It is the “sentences” made with objects which have a meaning and not the single object in itself.’12

And what of the sentence fragment that makes up Twombly’s title for this 1954 piece? We are offered a supposed yet convincing function for the assemblage: the box that seems at first simply a base for the two elegant, sculptural uprights of the palm fans is in fact the content of the sculpture itself, for that base is a box and that box is one meant not merely to support but to contain – in this case the coiled carcass of a lime-green python. What we see, however, is the box, named funerary; no trace of a python; and certainly no trace of lime green. That colour exists first in the title and then in imaginary, but paradoxically lively, opposition to the shroud of white paint that coats palms and box alike. While the title offers an imaginary field in which to move or think in relation to this sculpture, it also returns us, by way of naming an absent colour, to the fact of white here, the physical fact of this thickly applied cover of paint as well as the scientific fact of white as the combination of all colours, lime green presumably included.

The at-once-ness of literal and allusive white paint, addressed above, now meets the seemingly contradictory, or at least discrete, quality of in-between-ness, registered in this case as what lies between the sculpture’s literal materials and its allusive title. Even so, here we must recall that the larger part of Twombly’s title functions as a parenthetical, after that initial laconic Untitled. Parentheses are used to bracket an insertion without which a sentence, or a meaning, would yet remain grammatically correct. Or, more loosely, to bracket a digression, an interlude – better still, an interval. This title’s parentheses point to the literal, grammatical fact of the gap as well as to the idea of the gap, the idea of the space-between. They lend the sculpture a specificity of purpose while reminding us of those gaps between categorical specificity and tangible reality: the gap between a so-called funerary box and a flat, upended, simply crafted wooden box veiled by a layer of house paint; the gap between an absent lime-green python and the whitened presences of dried palm leaf fans, wire, wood, and cloth; the triangular gap between a coffin, an assemblage of things, and a sculptural object. This is what happens when words both do and do not fit their things – and it is into these gaps that Twombly’s sculptural things themselves fit.

A word that is often fitted to Twombly’s sculptures of the 1950s is fetish, which stretches back etymologically to the Latin facticius, our ‘factitious’, an artificial or a made thing not so unlike the Greek for poem. The word is used widely in Twombly scholarship, and often without historical or anthropological particularity, instead applied for its material and morphological assonances. It becomes a catch-all term for objects that read as ‘primitive’ (often enough a catch-all, itself, to be sure) – handmade, ‘folk’ or even ‘amateur’, archaic in sensibility, and above all imbued with a potency that belies the stuff of which they are made. The catch-all aspect of the term goes hand in hand with its more technical indeterminacy. There are important examples of fetish as determined – the language of the sexual fetish or the commodity fetish – but Twombly’s engagement remains a formal and affective one, moderated by his travels, his interest in ethnographic and archaeological objects, his penchant for symmetry, and his attraction to ritual and myth as much as to history.

Well before his 1952–3 trip to Italy and North Africa with Rauschenberg, critics and fellow artists had articulated the presence of fetish-like forms in Twombly’s paintings.13 While traveling overseas, Twombly made sketches of various charms and tombstones, among other objects, which he saw in North Africa and in Rome’s Luigi Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography.14 During the same trip Rauschenberg created and then largely destroyed a series of sculptures called Personal Fetishes.15 And upon his return, Twombly would refer to his own sculptures of the mid 1950s as his ‘African things’.16 Beyond this code of personal naming, discourses of the so-called primitivist fetish had persisted through earlier modernisms to flourish again at mid-century, everywhere from surrealist-inflected painting to poetic convictions about the glyphic figure. Some of Twombly’s self-labelled ‘African things’ are smaller twined or bundled objects; others, including the original version of the 1954 sculpture, are totemic, with animate mirrored and swinging components. They are made from what is to hand, and by their very held-togetherness, otherwise ordinary parts become effective as affective wholes.

My first extended engagement with Twombly’s sculptures came by way of the Rauschenberg photographs, these compelling and somehow ceremonial gatherings of luminously painted, abstract yet defiantly material things. Ceremonial gatherings but also simply a kind of storage-like, in-studio arrangement, exalted as much by our admission to the private workplace as by the act of photographic framing. But the primary available photograph of the 1954 object is no less loaded: the lushly silver-toned picture that represents the piece in the Catalogue Raisonné as well as in most other illustrated texts (fig.1).17 In this image the sculpture’s diverse material make-up remains legible, but so does an idealised, and downright attractive, sculptural autonomy – a still more central theme of modern and modernist sculpture than the fetish-like assemblage, and indicative of its own brand of fetishisation (via aestheticisation).

Once again we see Twombly’s sculpture function within a gap or interstice, for between these two photographs (figs.3 and 1) are posited two kinds of modern sculpture: the in-process studio object, in which found fragments of the literal world are powerfully juxtaposed, and the self-sufficient, self-reflexive artwork whose impact is that of the unique object rather than of the concatenation of mere things. Twombly manages to retain and maintain both positions. Indeed, I see the Funerary Box sculpture, in its final version, as a liminal piece between the terms of the term fetish and the terms of the still Western but more classical term monument, the latter no less freighted a word for the history of twentieth-century sculpture than the former is freighted for art history and the histories of ethnography and colonialism alike. The vexing of that word monument within modern sculptural narratives is more than we can account for in the space allotted here, but it has grown an evermore forbidden term since the beginning of the twentieth century. Its traditional associations with historical commemoration, the prominence of a grounded base, the grandiosity of scale, and the oft-invoked materialities of bronze or marble or stone have long been rejected as too traditional, thus irrelevant. Yet memory, place (whether the site of a base or the location of production, or both), scale, ‘marble’, and, as we shall see below, bronze, are in fact richly relevant to – as well as, in some cases, critically nuanced within – Twombly’s sculptural practice. And though monument reads as the ‘high’ term to the ‘low’ term fetish, in a grant application from 1952 Twombly wrote of his interest not simply in ‘primitive’, ‘ritual and fetish elements’ but in what he found ‘peculiarly basic to both primitive and classic concepts’: the peculiarities of a coincident or doubled plastic language.18 Fetish and monument, ‘primitive’ and classically Western at once – Twombly’s convictions about at-once-ness yet again fostering, however counter-intuitively, a terminological, ideational, and sometimes even material space for in-between-ness.19

The confluent motifs of ‘monument’, more modest ‘marker’, and occasionally inscribed ‘epitaph’, persist in Twombly’s sculpture to the present day, though some of the specificity of the ritual or fetish form falls away by the end of the 1950s. What Twombly removed from the 1954 sculpture in order to arrive at its finished state were its more literal fetish-type elements, after all – those flashing mirrors and both the swinging and the upright appendages. Still, the collision between fetish- and monument-types persists in Twombly’s sculptural objects across the decades largely as a matter of scalar register and scalar resonance. The 1954 piece, as with all of Twombly’s three-dimensional work, remains object-like in scale, not at all monumental in its measurements. As a supposed funerary box we could even understand it as literally scaled: this is the size of the very box that marks the python’s funereal site, however unusually portable that site. But the sculpture additionally achieves the aspect of a model for a monument, a sort of scalar promise, never attaining the scale of the typical monument-as-such but operating as an object whose scale seems simultaneously appropriate and unfixed, and whose impact is ‘larger’ than size might seem to prompt. (If scale, unlike size, is to do with proportion, remember this unfixedness of scale is in part in relation to our own bodies, in part in relation to the expectations raised by the sculpture’s affective appeal.) Model itself remains a usefully unfixable term: a copy, a mock-up, a paragon, and an object that has been compacted in its scale in relation to some real or imagined ‘original’. This is a sculpture that does not allow names to stick, that does not stay stuck within the art-historical categories on offer but prefers to be suspended between names or categories, without seeking in turn to suspend the categories themselves. It is this latter point – suspension between without suspension of – that allows for my own theoretical languages of at-once-ness and in-between-ness to work in concert rather than in contradiction.

In turn, we could discuss the frontality of this 1954 sculpture: it and the other larger totem-type pieces command a vertical and direct address. We are face to face with these objects, as if in physical as well as conceptual dialogue. At the same time, such frontality could read as decidedly high-modernist, uninterested in the anthropomorphic bodily address but rather in the potential pictoriality of modernist sculpture that was its advantage for prominent critics like Clement Greenberg at mid-century. Sculpture, for Greenberg, must avoid the state of the everyday thing, but the fact of its concreteness, the fact that it could never fundamentally avoid being a literal object in three-dimensional space, allowed it the leeway to approach the realm of the two-dimensional, of the flat, optical, and pictorial.20 Or, to invoke another important high modernist critic, Michael Fried, the internal relationships of this sculpture – not its way of relating to us as viewers but its internal grammar, the way each of its parts is in dialogue with the next – would be what renders it a compelling modernist work.21 Yet we already know that syntax is ascribable to both modernist sculpture and fetish object, if we recall Lévi-Strauss’s understanding of bricolage as word-like objects that together make a meaningful sentence.

Neither Greenberg nor Fried wrote about Twombly’s sculpture,22 nor was the artist included in William Seitz’s 1961 The Art of Assemblage exhibition at MoMA, in which so many of his peers, Rauschenberg among them, did appear. While elaborating an art history based in the analysis of exclusions (what did not happen, what is not there) is itself suspect, it is my suspicion that Twombly was excluded on these counts not only because he was then living overseas and taking a substantial break from sculpture but also because his three-dimensional works are best read between the assembled, bricolaged, fetish-thing and the modernist sculptural isolate. In fact, the fetish object can itself remain useful as an indeterminate term: for scholar Tomoko Masuzawa the fetish is ‘at once an idea and an object’.23 I would even prefer the word thing here to Masuzawa’s object, because it is yet another term, not unlike fetish, that oscillates radically, a word that owns its ambiguities. It is the word for that which is not, need not, or cannot be named, whether a concrete, physical, tangible thing; an ephemeral, conceptual, notional thing; or an anything, a something, a nothing.

The understanding of a fetish as at once idea and thing calls to mind the decidedly unspiritual or aspiritual 1926 edict of poet William Carlos Williams: ‘no ideas but in things.’24 It, too, is a surprising knot of a phrase, not half so straightforward as it is streamlined. Simple reference to it here, however, can remind us once again of the imbrications of idea and thing, word and thing, and word or poem as thing that inform the history of modernist poetics as much as they seem to inform Twombly’s practice. Much work needs to be done on the relationship between Twombly’s sculpture and modernist poetics – not just in light of poets Charles Olson and Frank O’Hara, who wrote about Twombly, but in light of a shared preoccupation with the potential mutuality of verbal constructions and object constructions, verbal constructions as object constructions and vice versa.25

For now I will instead offer up a counter to the mid-century intimacy between word and thing, since we have learned that Twombly’s sculptures function as though suspended between two points rather than subscribing to either. One feature of the obdurate materiality of these sculpture-things is, anomalously, their open-endedness, their slipperiness, their allusions that are identifiable enough but then refuse the satisfaction of closure. Although I have no little conviction about words as things, words are also absences, virtual placeholders for the physical thing that is there in name only. Twombly is not unaware of this marking of absence, even while his processes of mark-making necessarily manifest a new material presence in the world. For instance, we can point to erasures, crossings-out, and whitings-out in his work across media. The sculptures, in particular, are almost always whited-out, a practice that does not render them ghostly so much as it veils one kind of obdurate material with the open field of another kind of obdurate material. But in an untitled sculpture of 1985 (fig.4), Twombly has actually inscribed a title onto a surface, only then to paint it over, to white it out.

![Cy Twombly Untitled [Bassano in Teverina] 1985](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/cy_twombly_untitled_bassano_0.width-420.jpg)

Fig.4

Cy Twombly

Untitled [Bassano in Teverina] 1985

Cy Twombly Gallery, The Menil Collection, Houston, Gift of the artist © Cy Twombly

The sculpture was made alongside a series of paintings, rare for Twombly who tends to separate his genres, and those five 1985 canvases are called Analysis of the Rose as Sentimental Despair. They include lines from Rainer Maria Rilke, Giacomo Leopardi, and Rumi, though the title is Twombly’s own humid fragment. The sculpture was granted no title, nor is it a frontal box, as the python piece of thirty years prior. Instead, it is a box that is exhibited as an almost-horizontal, to be looked down upon if also to be seen and read around (viewing in person, one must crouch to the ground in order to take in the box’s sides at eye level). One of its side faces bears the partially readable traces of Twombly’s titular phrase in red, smudged out again in white (fig.5). The title of one set of paintings is named in their absence as we look instead at a sculpture; then that name itself is made mostly absent.

![Cy Twombly Untitled [Bassano in Teverina]1985 (detail)](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/cy_twombly_untitled_bassano_detail_0.width-420.jpg)

Fig.5

Cy Twombly

Untitled [Bassano in Teverina]1985 (detail)

Cy Twombly Gallery, The Menil Collection, Houston, Gift of the artist © Cy Twombly

Photograph: Katharina Schmidt

I invoke this later sculpture at my conclusion as in as many ways distinct from the Funerary Box as it is consistent with it. There is no effect of the totemic, for example, in the later work, though it has been likened to an altar.26 But I will conclude more formally still with a work from 2002 (fig.6), version one of two bronze pieces cast in Rome from the 1954 Untitled (Funerary Box for a Lime Green Python), which has so long been in the artist’s possession. Twombly has occasionally cast both older and more recent sculptures in small bronze editions since 1979. In this instance the revisitation and recycling of a nearly fifty-year-old work serve further to align within the object itself the oddly unframeable thingness of the fetish with the unitary permanence of the (traditionally bronze) monument.27 This leap, as well as link, between 1954 and 2002 reminds us that Twombly’s sculptures, even when most readily assigned to a category like monument or marker, are always already opened out onto alternative modes of objecthood or thinghood: sculptural object, felicitous aggregation, monumental model, lyrical thing – all of these at once, courting the discomforts of in-between-ness and simultaneity rather than the ease of exclusivity.

Fig.6

Cy Twombly

Untitled (Funerary Box for a Lime Green Python) 2002

© Cy Twombly

It is the significance of the categorical, or the attempt at the categorical, the practice of naming or trying for a name, however fleeting or conflicted, that I hold onto here. This is where Twombly’s decades of sculptural production are most apposite and instructive today. There has been a much-discussed resurgence in assemblage-type sculpture, a widely apparent contemporary concern with heterogeneous materialities rather than with the sculptural object whole or proper, but Twombly has consistently managed to situate himself between these two categories without voiding or invalidating either one. The ethics of this in-between-ness are not studied or deliberate although neither are they of merely casual import, not least because they prompt us to investigate the ethics of the art historian’s task, our search for functional gaps of our own: that interstice between the descriptive and the ekphrastic, for example, or that veritable chasm between the categorical and the expansive, our task being one that must ever assign words to things. Thus, Twombly’s things are simultaneously challenging and sympathetic invitations to just such continued activity.