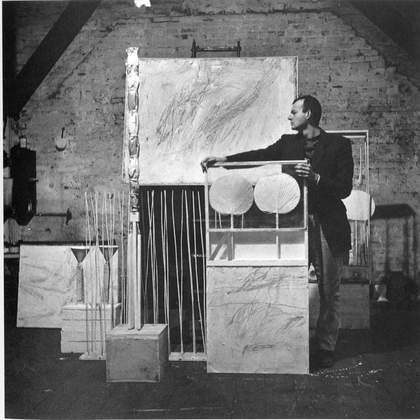

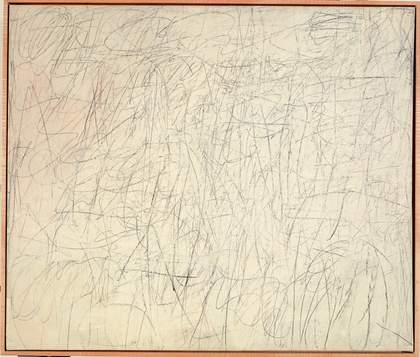

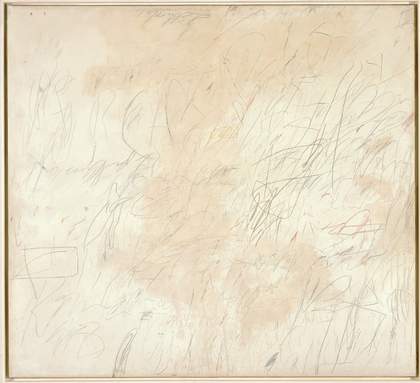

Fig.1

Cy Twombly

The Age of Alexander 1959–60

The Menil Collection, Houston © Cy Twombly

During the 1950s Cy Twombly’s life and career took what appears to be an epic path: from student at Black Mountain to artist with an international audience; from New York’s creative ferment to Rome, capital of la dolce vita; from the sphere of Robert Rauschenberg and Leo Castelli to a family life amidst the Italian aristocracy. At the end of that eventful period, during the New Year holiday of 1959–60, the artist created a painting, the subject and scale of which announced its milestone status. The Age of Alexander (fig.1) is Twombly’s first ‘history painting’, executed in a monumental format, measuring nearly 10 feet by 16 feet,1 and signalling passage and commemoration (‘1959 into 1960’ as the pencilled inscription bleeding off the right side informs us). On the face of it, it is a tour de force, recalling the campaigns of Alexander the Great in impastoed, oil-paint globules and smears, in pencilled and crayoned scratches and graffiti. More carefully read, however, the personal blends into the historical. This painting marks both a beginning – the arrival of Twombly’s infant son, Cyrus Alessandro – and the apex and finale of a decade-long endeavour to establish artistic credentials. It is a mature outpouring that confirms a unique style, forecasts lifelong themes and aesthetic directions, and suggests both personal and cultural content.

However, The Age of Alexander also exhibits the antique references and humanist overlay that have occasioned both delight and derision among critics and viewers. In 1994 the painting was among those exhibited in the retrospective of Twombly’s works at the Museum of Modern Art. On this occasion, Artforum commissioned a pair of articles.

In his contribution, Peter Schjeldahl judged Twombly to be an artist of ‘medium-sized virtue’ whose ‘lingering grace note to the symphony of Abstract Expressionism’ is ‘split off from the spirit of truth-telling, which distinguishes living art from bric-à-brac.’2

In her piece, Rosalind Krauss complained that Twombly himself orchestrated scholarly opinion about his classical humanism. She asked: ‘Do we care: to what degree do we have to respect Twombly’s self-assessment?’3

Though Schjeldahl and Krauss represent duelling sensibilities, the editor found one important point of agreement, reporting that ‘both critics … go after the standard Twombly apologia as so much humanist drivel.’4 These have been typical responses in the United States, where postmodern scepticism has relegated Twombly’s humanistic tendencies to misguided nostalgia or irrelevance. However, in the America of the 1940s and 50s, during Twombly’s artistic upbringing, humanism was equated with freedom and was a liberal cause. Even during this period, however, humanist philosophies attributing essential, core features to human experience were challenged by ‘anti-humanist’ theoreticians who claimed that humans are constituted by historically specific systems of thought. According to this view, humans are incapable of acting on their environments; hence, history has no subject. The task confronting post-war humanists was to recognise the historicity of the ‘human condition’ and to jettison increasingly implausible universal terms while, at the same time, arguing for the autonomous individual who, situated within society and history, remains capable of creating structures and activating human attributes such as consciousness, agency, and moral value.5

I shall argue that Twombly’s oeuvre is distinguished – to the point of looking out of step with American production as early as the 1960s – by a nuanced, continuously-revised commitment to this discourse of humanism that was central to American left-leaning ideologies at mid-century. In this light, The Age of Alexander becomes a loaded consideration of one of the period’s most pressing issues: the construction of the human agent in the flow of history.

In works made between 1951 and 1953, we discover that the young Twombly emulated Abstract Expressionism in form and content. He was especially alert to the themes of archaism and ‘primitivism’ that informed many Abstract Expressionist representations. In January 1952, he confirmed this interest in a fellowship application to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, requesting travel funds. He wrote:

What I am trying to establish is – that Modern Art isn’t dislocated, but something with roots, tradition and continuity.

For myself the past is the source (for all art is vitally contemporary). I’m drawn to the primitive, the ritual and fetish elements, to the symmetrical plastic order (peculiarly basic to both primitive and classic concepts, so relating the two).6

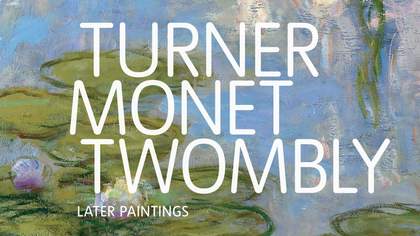

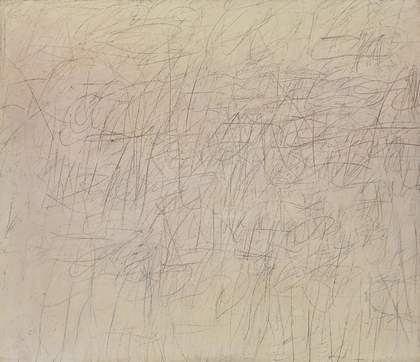

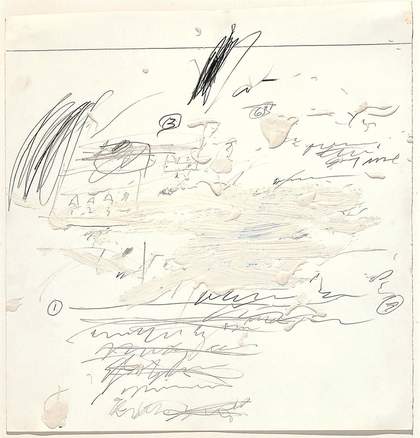

Fig.2

Cy Twombly

MIN-OE 1951

Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Collection © Cy Twombly

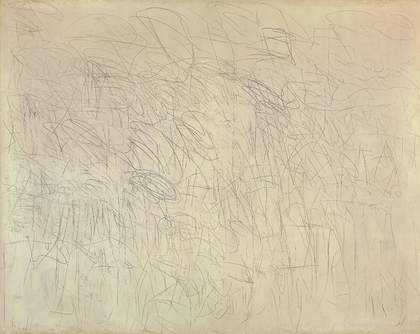

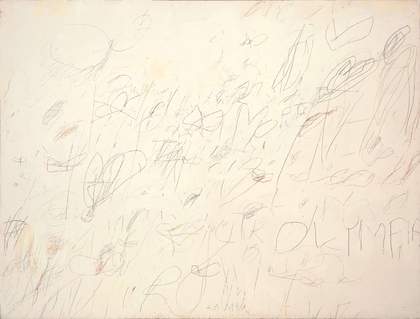

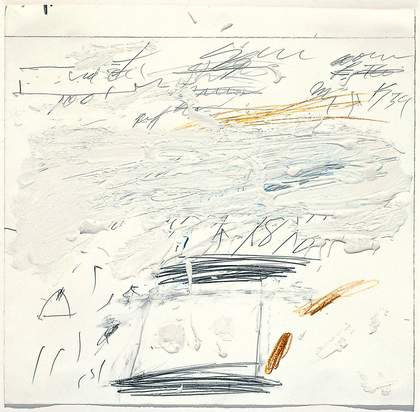

True to his words, Twombly produced paintings and sculpture that conjured the past. MIN-OE, 1951 (fig.2), is one of a group painted at Black Mountain, inspired by the anthropomorphic, often doubled, forms of Luristan bronzes. Tiznit (fig.3) and Quarzazat (fig.4), both of 1953, relate to places and traditional structures that he encountered on his subsequent trip to Morocco.

Fig.3

Cy Twombly

Tiznit 1953

Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York © Cy Twombly

Fig.4

Cy Twombly

Quarzazat 1953

Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York © Cy Twombly

However, judging from these works, Twombly’s research uncovered a dark strain in the continuities between ancient and modern. Symmetrical order surges with elemental emotion or danger. Dualities are evoked in the stark contrasts of palette, the prickly erectile forms, and the worn surfaces, but we are left with uncertain conclusions about the dialectic between good and evil, life and death, the beastly and the human.

The works, along with Twombly’s intention to find ‘roots,’ should be interpreted in relation to a question that nagged at Americans during this era. Why had human beings failed to resist the events and systems that had produced worldwide calamity? A sense of moral bankruptcy, anxiety, and confounding dichotomies penetrated post-war American life despite new material well-being.

Mitigating this anxiety, however, was the hope that a return to humanistic values could somehow redeem human behaviour. The Abstract Expressionists and Twombly, their acolyte, participated in this cultural work, and queried the past for larger, healing truths. The prevailing assumption was that, if one could locate archetypes – the continuities of history and myth – or find the parallels between so-called primitive societies and modern ones, insight would be gained into some set of universal, timeless conditions or some unshakeable moral foundation that might recuperate contemporary life. In 1946 Mark Rothko suggested the desired outcome as he referred to his colleagues as a ‘small band of mythmakers’, charged with ‘creating new counterparts to replace the old mythological hybrids.’7

This search for a unifying essence or source of humanity was complicated by a countervailing turn from collectivity toward the self, a turn notably present in the Abstract Expressionists’ emphasis on subjectivity. A dense body of scholarship has revealed that the Abstract Expressionists’ understanding of subjectivity paralleled that of left-wing intelligentsia of the time.8 Frankfurt School social theorists, Jean-Paul Sartre, C. Wright Mills, and Dwight Macdonald all contributed to the mix of Marxist, Existentialist, and American Pragmatist theory known to the Abstract Expressionists.

In general, these artists and intellectuals, acknowledging the failure of collective bodies (particularly the working class) to avoid totalitarianism, argued that human freedom was threatened by over-determined, instrumentally-rationalised forces embedded within social structures. Their targets included both capitalist and Marxist economic systems, unfettered mass media, and blind trust in the science industry. To oppose collective forces, the left wing placed the responsibility of moral agency on the individual. Ultimately, subjectivity was constructed as the power to wield non-rational, intuitive, and emotional knowledge against tyrannical reason and mass culture, thereby asserting freedom.

According to this formula, artists had a special role. They were conceived both as having more penetrating access to the non-rational forms of knowledge and experience, especially the imagination, and as being alienated from entrenched power structures, hence, less susceptible to mass mentality. In theory, artists had an increased ability to expose the corrupted world order and potentially to conceive alternative ones. Privileging the artist’s subjectivity served to move critique and protest to the aesthetic sphere, away from the socio-political realm.

Twombly would have been well exposed to this discourse. Among artists, Robert Motherwell, who would become one of Twombly’s mentors, actively argued for subjective expression of humanist values and for the artist as author of critique. In 1948, he wrote of modern art becoming a ‘peculiarly modern humanism’ through which ‘humane men [defend] their values … against the property-loving world.’9 In 1950 he declared that art, ‘might be summarised under the general notion of protest,’ ‘a kind of dumb, obstinate rebellion at how the world is presently organised.’10 Motherwell assiduously developed this polemic, in prolific writings and in paint, notably in his long series, stretching from 1948 to 1991, Elegy to the Spanish Republic.

Over and over again during the late 1940s and early 1950s, Twombly would have heard many other voices invoking humanism in the cause of freedom. Dwight Macdonald, a well-known public intellectual, urged Radicals to think in ‘human terms’ in his seminal essay of 1946, ‘The Root is Man’.11 Similarly, Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, working together in the United States, echoed Marx and wrote of the loss of a ‘truly human condition’ in Dialectic of Enlightenment in the mid 1940s. Of particular importance because of its broad dissemination was the strident humanism of Existentialism. Jean-Paul Sartre, virtually a pop-culture icon in America, firmly set the parameters of his theory of freedom, writing Existentialism is a Humanism in 1946.12

Twombly’s early production should be viewed as inscribed within this humanist project oriented toward the assertion of subjectivity and freedom in an increasingly alienating and homogenising world. Twombly’s works are imbued with the anxieties, priorities, and theories of the immediate post-war era. The uncertainty of the period is communicated in the muddied contrasts, the repeated, injured forms, the fevered brushwork, and the crumbling, crude geometries and patterns.

They raise intransigent questions relevant to the time. Does the so-called ‘primitive’ mind have more emotional, intuitive depth and humanity than the reasoned, controlled, modern one? Are enlightenment and myth the same? Is timelessness an illusion of circularity, recurrence, replication? Can the universal be revealed through a subjective and particular vision? Twombly’s early works owe a great deal to the Abstract Expressionist paradigm, explicit as they are in their themes and subjective perspective. However, they also appear less dramatic and situational than the offerings of Pollock or de Kooning whom Twombly admired.

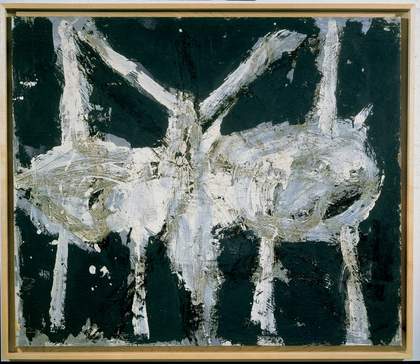

Fig.5

Cy Twombly

The Geeks 1955

Private collection

Courtesy Thomas Ammann Fine Art, Zürich © Cy Twombly

In fact, by 1955, a significant change had occurred. Paintings, such as The Geeks (fig.5), Free-Wheeler, Criticism (fig.6), and Academy (fig.7) are inarticulate and unsettled. Though the surfaces are energised, the movement is frenetic and spasmodic. Between 1951 and 1955 Twombly constantly moved from place to place: up and down the East Coast, to Europe and North Africa. Then, for less than a year, in 1953 and 1954, his freedom was constrained by Army service and his assigned duty as a cryptographer. It was during this time that Twombly made what he considers to be breakthrough drawings, brought to fruition in New York in the 1955 paintings.

Fig.6

Cy Twombly

Criticism 1955

Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York © Cy Twombly

Fig.7

Cy Twombly

Academy 1955

Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York © Cy Twombly

The pinched, compulsive quality of these works may channel the frustration and uncertainty of vaulting from life as an artist to that of disciplined conscript. However, they also describe the stifling times and the paranoiac atmosphere of Cold War America. The fact that protest had been moved to the arts was branded as either quiescence and co-optation or a dissent so coded that it was unintelligible to the masses.

This silencing had been enacted at Black Mountain College in North Carolina where critique literally moved out of the socio-political world and onto a southern-style Parnassus. By the time that Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg attended sessions in 1951 and 1952, Black Mountain had become a refuge for disenfranchised New Deal leftists, like Ben Shahn and Aaron Siskind; an array of Abstract Expressionists, including Motherwell and Franz Kline; and the poet-essayist, Charles Olson, rector of the College, whose political troubles were such that the FBI visited in the summer of 1952. These older leftists fashioned a laboratory for the next avant-garde generation, attracting Rauschenberg and John Cage, who would remain in Twombly’s circle. Olson, more chaos-inducing impresario than dignified tutor, encouraged what could be described fairly as a convention-flouting community of academics, geeks, and free-wheelers whose fate and foibles may well be insinuated in these paintings.

These canvases have been read as an upstart’s response to the authorial dictums and muscular style of Jackson Pollock. Certainly, Twombly does take on the reigning avant-garde. He reduces their confident sweeps of paint to pencilled scribbles and erasures; he subverts their solemn renderings of the tragic or sublime with satiric outbursts of the ‘f’ word.

The paintings are impure and taunting. Expletives, intelligible or not, mark and mar the canvases signalling a start to Twombly’s long disquisition on the paradoxical relationship of word and image and of writing and drawing. And, in doing so, Twombly reveals himself to be an artist rude enough to ignore the etiquette that separates them. He sullies and confuses both the sacral field of paint and the metered, formed domain of words. If the titles were arbitrarily chosen as is claimed, then the results were fortuitous in the extreme. More likely, Twombly treats us to some of his cryptographer’s obfuscation. The word-and-picture-play is laden with possible ironic reference to his own life’s circumstances, and to mentors, allies, and critics. Canny, subversive tactics abound.

The randomness and disrespect that infect Twombly’s 1955 canvases display a shifting sensibility. Apparently, Twombly does not aspire to use his subjectivity for mastery. There is no interest in taming and controlling his media nor in presenting anything like a unified vision. The heroic power, sensuality, and fluidity of the Abstract Expressionists has dissipated into stuttering, indeterminate parries. The existential struggle against contingency is replaced by acceptance, if not an embrace, of chance, ambiguity, and chaos. The unavoidable implication is that the theoretical apparatus of his predecessors requires adjustment.

These works illustrate Twombly’s engagement with many of the ideas and practices circulating at Black Mountain. The College was founded on the educational precepts of the American pragmatist, John Dewey, who rejected foundational knowledge and subject/object dualism in favour of contingent, relative knowledge emerging from humans actively interacting with and adapting to the material facts of the environment. Not averse to science or its methodologies, Dewey’s naturalistic approach emphasised experiment in which knowledge accrues and evolves from the trial-and-error process of inquiry itself.

Under Olson’s tenure, these emphases on interaction with the material world, experimentation, process, and contingency reached a fevered pitch. His personal trajectory, going from loyal Roosevelt bureaucrat to suspected ‘Red’ sympathiser, had turned him rabidly anti-authoritarian and against mass culture. Anger and political impotence motivated his plan for ‘the restoration of the human house.’13

In two controversial essays, ‘Projective Verse’ of 1950,14 and ‘Human Universe’ of 1951,15 he began to plot ‘another humanism.’16 His approach was an unprogrammatic, deeply personal incorporation of Ezra Pound’s poetics, twentieth-century theories of intersubjectivity and phenomenology, and Alfred North Whitehead’s philosophy of process and organism. Olson subverted both collective and subjective identity; proposed immaterial process to be reality; advocated organic, open form; and required participatory interpretation – all positions associated with Twombly’s generation and with post-modernism. Although Olson was probably the first in the United States to refer to ‘postmodern’ society, his project outlines an alternative model of humanism – a most useful one through which to read Twombly’s works of the mid to late 1950s.

Olson’s central position was that, in Western culture, the priority of two intellectual forces, abstraction and self-reflection, had led humans to become estranged from their own bodies and nature. Olson hoped to return unity and balance by placing humans among other objects in the roiling, curving, contingent reality described by modern physics and non-Euclidean geometry. Humans would exist fully contextualised, as sentient objects situated in the same space and time as the objects of their perception.17

Olson became an enthusiastic advocate for Twombly, no doubt detecting a corresponding attitude. In 1951, Olson wrote: ‘what I like about Twombly is this sense one gets that his apprehension … is buried to the hips, to the neck, if you like’.18 This apprehension aligned with his vision of the artist whose ‘inner’ life and ‘outer’ life were enmeshed, whose body acted as a porous membrane, in which energy flowed in and out, part of an overall field of energy. In this field, all entities co-exist and ‘decide’ whether or not to take energy emanating from another entity. In this schema, everything is always in a process of self-formation, including the human subject who emerges from the facts and particularities of reality. More importantly, rationalised power structures are overthrown. Human balance and proportion are restored through a system of causal interrelationships, one object acting on another.19

In this kinetic, interdependent universe, humans did, however, retain agency. They alone could move from a state of pre-cognitive apprehension of universal energy, to a coalescing of knowledge gleaned from immersion in that energy, to the construction of forms that are derived organically from and in balance with what is known. In a poem of 1950, ‘ABC’s (2)’, Olson described a course from the pre-cognitive state of apprehension, to a coalescing of knowledge, to acts of human agency that include making art:

of rhythm is image

of image is knowing

of knowing there is

a construct20

Fig.8

Cy Twombly

Olympia 1957

Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York © Cy Twombly

For Olson, the activity – the process – of forming was a uniquely human mode of intelligence and the source of agency. According to Olson, ‘an idea means to see … Action is to move toward form. To act, then, is to go from to see to to do (to finish is to do, & so to make a poem, or anything’21 – presumably ‘anything’ like Twombly’s Blue Room or Olympia (fig.8) of 1957. These paintings figure instances of apprehension – cascades of spontaneous, incomplete perceptions – sharing a field with more fully developed images moving toward form. Olson used the body as a measure. He regarded each utterance to be an evocation of a moment’s energy, a physical exhalation of sorts, discharged without pausing to find the mot juste or, in Twombly’s case, the elegant line. Everything is put into motion, relationships occur, energies are transferred, and forms emerge naturally from content.22 Twombly’s haphazard, half-written words and poorly-determined strokes create a form uniquely his own, a hybrid of painting and poetry emanating from bodily surges of expression. Moreover, growing out of the context of Italy, the energy of these paintings seems euphoric and free-spirited compared to the taut productions made in America. For example, Arcadia (fig.9), of 1958, vibrates with ‘kinetic’ events and with Twombly’s ‘choices’ to merge his energy with ephemeral whiteness and Poussin’s legacy.

Fig.9

Cy Twombly

Arcadia 1958

Courtesy Daros Collection, Switzerland © Cy Twombly

The series, Poems to the Sea (figs.10, 11), of 1959, makes manifest Olson’s demand that humans must find their proper relation to nature and look to it for the principles of formation that ceaselessly advance from it. In 1957 Twombly described a ‘synthesis of feeling, intellect etc. occurring without separation in the impulse of action.’23 As Olson would have liked, each image is a site of activity – of sensate energies transformed to intellection, then action. As a group, we see serial experimentation and a succession of phenomenological states. An open architecture of knowledge emerges – instinctual, emotional, abstract, logical – all formed from nature organically, if not always coherently or smoothly.

Fig.10

Cy Twombly

Poems to the Sea 1959

Dia Art Foundation © Cy Twombly

Fig.11

Cy Twombly

Poems to the Sea 1959

Dia Art Foundation © Cy Twombly

To further harmonise man with nature, Olson advocated a return to ‘mythic consciousness’, the state before logos and the human urge to dominate became the rule. To locate it, Olson envisioned a new archaeology in which past, present and future history penetrate one another, in paratactic arrangement, to reveal and create metaphors and narratives useful to modern life.24 The Maximus Poems, a sprawling epic work begun in 1950 and unfinished at Olson’s death in 1970, fashions an anti-hero, Maximus of Gloucester, Massachusetts, who intersects with Maximus of Tyre to tell the story of his town and its relationship to the sea. Taking the mythmaker-historian, Herodotus, as his guide, Olson understood the verb istorin – to mean the action of ‘finding out for oneself.’25 As far as Olson was concerned, history, ‘WOT ’APPENED?’, was in one’s own hands:

Two alternatives: make your own story – fiction, or history: when you are up against it, to equal what went on. One can know what one oneself makes, but to know what happened, even to oneself? … It isn’t a question of fiction versus knowing. ‘Lies’ are necessary in both – that is the HIMagination. At no point outside a fiction can one be sure. What did happen? Two alternatives: make it up; or try to find out. Both are necessary.26

Twombly uses a similar approach in The Age of Alexander. He vacillates between heroic and personal history, grabbing and layering bits and pieces of time and space. Events of the past, Alexander’s campaigns, exist on the same plane of reality as Twombly’s present and the infant Allessandro’s future. Twombly’s journey into the moment is felt in intimate, immediate terms and in global proportion. It is fragmentary and incidental, residing on the canvas and across continents.

Twombly’s marks, themselves, resonate with primal signage and utterance. They range from the liminal, pre-linguistic, and proto-symbolic to tumbling geometry, and disjunct verbiage. They are akin to the ideograms and glyphs that Olson believed were less mediated than modern language, thus, retaining the power of experience.27 Olson had already found this materiality and directness in Twombly’s productions of 1951, when he declared: ‘the dug up stone figures, the thrown down glyphs, the old sorrels in sheep dirt in caves, the flaking iron – these are his paintings.’28

The goal of humanism, generally, has been to find eternal truths about the human’s status in creation. However, in Olson’s ‘human universe’, truth, like the human object, does not exist independently and is constantly unfolding. The only means to form human truth was through a commitment to the action of perception,29 ‘the scrupulous assertion of one’s self on the only reality which counts … that which is bearing on us at this instant.’30 And the highest degree of perception in the here and now necessitated being fully open to the past, present, and future. Perception and truth were no less than the intersection of the individual and particular with the absolute and universal. ‘No event,’ Olson claimed, ‘is not penetrated, in intersection or collision with, an eternal event. The poetics of such a situation are yet to be found out.’31

Twombly located the poetics. As the calendar turned from one decade to the next, Twombly was moved to engage in the phenomenal reality that enveloped him in that particular place and time in Rome. The Age of Alexander has the aura of something deeply felt and private. At the same time, it communicates realities common to all human beings. In league with Alexander and Allessandro, Twombly brought forth the conditions we all recognise in human passage – birth and death, triumph and calamity, hubris and humility, the memorable and the forgotten, the epic myth and the cautionary history.

In Twombly’s hands the lessons of the new humanism were twofold. First, history and myth are chronicles of human action and making. If there are any absolutes or universals that form a core of human commonality, it is the sheer process, the compelling action, which moves us toward some meaningful end. Second, it is the finding of the meaning that is singular, particular, and transcendent. In this endeavour, we have Twombly ‘making’ history, formed not as a succession of events, but as sets of interpenetrating, active, indeterminate relationships.

As the 1960s arrived, Twombly would step into the rich traditions of Italy and add new layers and critiques to his consideration of humanism. However, his commitment to humanistic study grew out of his own penetration of American culture at mid-century.