Speaking of the grand long take at the end of Andrei Tarkovsky’s final film Sacrifice (1986), during which the protagonist’s house burns down to the ground, the French filmmaker and multimedia artist Chris Marker has claimed: ‘This scene had to be shot in a single take in which the tracking shot is no longer a matter of ethics, but of metaphysics’.1 Marker intriguingly suggests that the distinctive aura surrounding the Russian film director might not be just the afterglow of his personal charisma or the reverential glow inspired in some by his Delphic pronouncements on religion and world destiny, but also a matter of his cinematic technique. Can it be that Tarkovsky’s cinema intervenes in elements, like vision and time, which have traditionally been the province of metaphysics? And how does this intervention remain relevant in our post-metaphysical age?

Of course, the cinema has always been metaphysical. Its origin as a concept has sometimes been located in Plato’s allegory of the cave, which first identified the attractions and dangers of observing images projected onto a flat surface.2 As images have proliferated in modernity, there has been a growing anxiety that we have been moving gradually but unerringly further away from the direct light of reality, into a sealed chamber of shadows. Largely on the basis of his own writings, particularly the book published in English in 1989 under the title Sculpting in Time (the Russian title means literally ‘Imprinted Time’), Tarkovsky’s project has sometimes been characterised as a rearguard action aimed at retrieving a semblance of the real by ignoring the mediation involved in any representation, pretending that the shadows on the wall still magically capture some divine light, though they be produced mechanically, digitally, etc. I shall argue that, if Tarkovsky sought to discover a new sense of the real, it was only within the medium itself; and if he sought to represent mystery, it was the mystery of mediation. It is as if an inhabitant of Plato’s cave relinquished the need for representative figures and focused instead on the revelation of light, shape and shadow – the fundamental forces that condition and comprise the images that mediate our experience of reality, forces which to an ever-increasing degree manifest themselves only within technological projection. It was this discovery of the real – of the material, the corporeal – within the very medium of representation that makes Tarkovsky of abiding interest for a fair number of contemporary artists.

My investigation into the concepts of medium and mediation, which emerge from Tarkovsky’s creative oeuvre, has four parts. First, I shall examine Tarkovsky’s ontology of the cinematic medium as encapsulated in his concept of ‘imprinted time’ and as exemplified in his films. I shall then cast quick glances laterally at Man Ray and Chris Marker, artists who seem to me to have made similar moves in their work, and then at contemporary artists who have explicitly acknowledged Tarkovsky’s influence or appropriated his images. This allows me, in conclusion, to trace Tarkovsky’s less conspicuous presence in contemporary video installation art, most notably by Mark Wallinger and Douglas Gordon, both of whom are media artists in the sense that they foreground the problem of mediation.

Tarkovsky and the medium

Tarkovsky’s first fully independent feature film Andrei Rublev (1966–9) told the story of Russia’s greatest icon-painter, a fifteenth-century monk who had recently been conscripted to serve in the atheistic but fervently nationalistic Soviet Union as Russia’s first great artist. It might seem that, by photographing the icon, Tarkovsky was seeking to redeem cinema projection by inscribing it into the history of the sacred image.

This would be a noble endeavour, one that has been suggested by no less an authority than the French film director Jean-Luc Godard, who notes that the Russian language has two words for image: ‘one for reality, Clic-Clac-Kodak, and another which is greater, deeper, farther and nearer, like the face of the son of man after it was projected onto the veil of Veronica’.3 Furthermore, critics like Paul Schrader have used the Orthodox icon as a model for the image in Robert Bresson and other ‘poetic’ filmmakers.4 However, it is not necessarily true that reproducing the icon via modern media of projection would restore its spiritual dignity; quite the opposite might be expected to occur. After all, as the icon has become more recognised in the West (and more accepted in post-Soviet Russia), copies have proliferated to the extent that it has become widely parodied and Photoshopped, a development for which Tarkovsky might share in the blame, having been one of the first to feature the icon in modern mass culture. Here the lofty icon becomes a mass projection, distant from any transcendent signified, sharing a common, debased currency with any other example of modern image culture.

This is not the first time that social and technological change has redefined the very status of the image. For our purposes, the history of representation can roughly be divided into three distinct eras or regimes of the image, which emerge especially starkly in an examination of the history of the image in Russia. First, the icon in Russian medieval culture was considered to be an image of the divine, imprinted in matter by the action of divine grace. The iconic image sanctified the material in which it was imprinted and the viewers who venerated it. In the icon the representation restored reality to the world.

The modern period, beginning with the reign of Peter the Great, introduced the notion of the image as projection, superimposed onto the world with the intention of its re-making. An attribute of power, the spectacular image became the means by which ideological control was exercised and contended; the result was a virtual interface between individuals and the real in a social imaginary. The twentieth century witnessed both the totalisation of this imaginary and its crisis: in their vast proliferation images comprised an opaque edifice of power, a virtual reality that ceased to serve as ideological currency. In certain respects the Soviet imaginary at its peak coincided with late capitalism which, as the American literary critic Fredric Jameson has described it, ‘can no longer look directly out of its eyes at the real world but must, as in Plato’s cave, trace its mental images of the world on its confining walls’.5 Here, in short, the projected image supplants the material world.

In the ruins of the Soviet imaginary artists like Andrei Tarkovsky sought to critique the rule of the projected image and to recoup its potentiality vis-à-vis the real. This they did, in my view, not by rejecting the fate of the projected and mechanically-reproduced image but by affirming the materiality of its mediation. This constitutes an entirely new concept of the image not as icon or picture but as imprint, in which presence is retrieved through a heightening of absence.

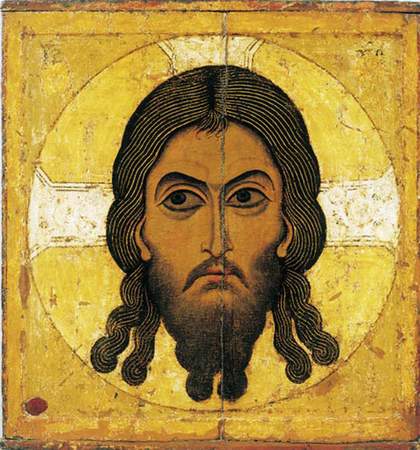

Tarkovsky worked in a new class of image, one that has defined his importance to contemporary artists. Of course, the imprinted image recuperates a characteristic of the original Orthodox icon, known as The Saviour-Not-Made-by-Human Hands (fig.1).

Fig.1

Saviour-Not-Made-By-Human-Hands

Russian icon from Novgorod c.11th century

According to the art historian Bissera Pentcheva, the ‘quintessential Byzantine image ideally should not be thought of as a painting created by brushstrokes but as an imprint – a typos impressed on a material surface. The relief icon most closely conformed to this theoretical model; it defined Byzantium as the culture of the imprint, mold, or seal’.6 The negative space of such imprinted icons forced viewers actively to construct a positive exposure by visually caressing the tactile surface; St John of Damascus speaks of ‘embracing’ the icon ‘with eyes and lips’.7 Especially when bathed in the candlelight of an Orthodox church, relief icons ‘deny the tangibility and even visibility of the sacred image’,8 insisting instead on the material icon as an artefact of mediation. While Godard insists on regarding even this icon – the Orthodox equivalent of Veronica’s veil – as a projection, Tarkovsky is more concerned with the way that, as imprint, it silently represents only the possibility of representation, rendering its own material basis as medium. In its very refusal to mediate it promises the possibility of mediation.

Owing to his metaphysical pronouncements and religious commitments, some critics continue to see Tarkovsky in the line of bombastic Russian artist-prophets who have viewed art forms as containers for sometimes retrograde ideological projects. His friends have sometimes contributed to this aura, perhaps unwittingly. Even Chris Marker, in his film-essay on Tarkovsky, makes prominent mention of the Russian’s alleged belief in occult forces and his participation in spiritualist séances, most notably one in which, through a medium, the late Boris Pasternak allegedly foretold Tarkovsky’s future.

Be that as it may, Tarkovsky consistently proved himself concerned most of all with another kind of medium altogether, that of the cinema. Even in his earliest films There Will Be No Leave Today (1958) and Steamroller and Violin (1961) Tarkovsky investigated how the elements of cinema reveal themselves on screen. Andrei Rublev was a study of both the analogies and the differences between the icon, the projected image and the imprinted image. This study was intensified in Mirror (1974) and Stalker (1979), which in Chris Marker’s words cease to rely on external ‘pretexts and rationales’ beyond cinema and discover the mysterious Zone of the screen-space itself. This lassitude before the medium has sometimes been interpreted – in my view, misinterpreted – as a naïve realism that obliges the viewer to accept a specific metaphysics. For Fredric Jameson the elemental character of Tarkovsky’s cinema implies a lack of sophistication and a naïve belief in the objectivity of the cinematic image: ‘The deepest contradiction in Tarkovsky is […] that offered by a valorization of nature without human technology achieved by the highest technology of the photographic apparatus itself. No reflexivity acknowledges this second hidden presence, thus threatening to transform Tarkovskian nature-mysticism into the sheerest ideology’.9 It is curious that Jameson contrasts Tarkovsky’s alleged mysticism to the cinema of Aleksandr Sokurov, whose verbose films, often with voiceover narration by the director, lend themselves far more readily to ideological reduction.

Tarkovsky was an artist at the end of modern art; his work can be interpreted equally as a gesture backward, pointing to former modes of representation and regimes of meaning, and as a gesture forward, pointing to newly emerging modes and regimes. If he sought to recoup the real, it was as a function of the projected image, as it is imprinted within the apparatus.

In a very different sense the concept of the imprint has been applied to photography, most prominently by Roland Barthes (in his notion of the ‘punctum’) and Jacques Rancière, who speaks of it as a ‘hyper-resemblance’ which ‘does not provide the replica of a reality but attests directly to the elsewhere whence it derives’:

Pure form is […] no longer counter-posed to bad image. Opposed to both is the imprint of the body which light registers inadvertently, without referring it either to the calculations of painters or the language games of signification. Faced with the image causa sui of the television idol, the canvas or screen is made into a vernicle on which the image of the god made flesh, or of things at their birth, is impressed. […] Compared with pictorial artifices, [photography] is now perceived as the very emanation of a body.10

Inhabiting a space beyond mimesis or projection, the imprinted image is ‘the legible testimony of a history written on faces or objects and pure blocs of visibility, impervious to any narrativization, any intersection of meaning’.11 Rancière’s explication of the imprinted image helps us to understand the peculiar poignancy of Tarkovsky’s films, which rests neither in their narrative nor in their ideological explication, but in the irreducible materiality of their projection.

Tarkovsky provides many examples of imprinted objects within his cinematic images. Andrei Rublev’s icons must be incinerated before their author accepts them; at the end of the film Boriska’s violent firing and smashing of the cast renews the image of St George by embossing it on a bell (fig.2).

Fig.2

Andrei Tarkovsky

Andrei Rublev 1966

St George embossed on the bell

© The Estate of Andrei Tarkovsky

In a majority of Tarkovsky’s films the imprinted image is dramatised in shots of coins, the study of which disrupts the narrative flow. The visitation of the mysterious guest in Mirror is prefaced by a long take featuring the boy Alyosha and his mother Natalia which situates the supernatural within the everyday. In her haste Natalia drops her handbag, and Alyosha eagerly begins to help pick up the spilled coins from the parquet floor, pressing them into his palm and tracing their design with his finger, as if recovering the material texture of history. When he reaches for another coin he quickly pulls his hand away, explaining that he had received an electric shock; he then smirks and remarks that he is experiencing déjà vu: ‘It’s as if all this has already been once, though I’ve never been here before.’ Natalia answers: ‘Give the money here. Stop imagining things, I implore you.’ Here the imaginary is not opposed to the material; it is precisely Alyosha’s vivid imagination that restores his tactile sense, just as it is Natalia’s distraction that both alienates her from the physical world and renders her insensitive to her son’s revelation. Throughout the shot Eduard Artem’ev’s electronic score builds to a harsh crescendo that prepares the viewer for the irruption of outside forces. However, this discontinuity is embedded within the fluid continuity of Tarkovsky’s signature long takes, which insist on the integrity of the experience. Nothing decisive seems to happen, but the complex confluence of temporalities within the shot bears a tactile charge, analogous to the way the coins conduct multiple dimensions of physical and psychic reality: material forces converge with the less tangible currents of memory, fantasy and vision in a single imprint of currency. When the mysterious guest disappears, we might suppose she had been a mere hallucination, were it not for the imprint of her tea-cup in condensation on the table. What is mysterious here is not the supernatural signified but the very possibility of a material trace.

Coins play an analogous role in Solaris (1972), Stalker (1979) and Sacrifice (1986). In Solaris they are Soviet coins contained in a metal syringe case that Kelvin takes with him to the spaceship and which then re-appears in his dreams of home. In Stalker pre-war Estonian coins feature amidst the submerged detritus of civilisation that the camera surveys in a sweeping dolly-shot over the waterlogged landscape, while the titular character lies asleep on a patch of mud. In Sacrifice Alexander dreams of uncovering a hoard of coins near Maria’s house; the coins are impossible to identify because of the high contrast of the dream sequence, shot in black and white. In all four cases the coins feature in Tarkovsky’s characteristic long takes: except in Sacrifice, the coins disrupt the fluid flow of the narrative fiction with the imprint of a specific historical moment. In all four films the coins also mark the borderline between waking reality and the world of dream, the palpable membrane that conducts the commerce between these distinct orders of reality. Thus, while conveying to the viewer a sense of confidence in the predictable continuity of experience, the coins also raise the potential (or threat) of hidden forces within the visible field.12 It is not the point for us to sort out what here is real and what is fantasy; reality is reclaimed as the friction between orders within the image, that is, as the stuff of time. Time, for its part, becomes palpable as the material basis of the image, as medium (figs.3,4).

In his writings Tarkovsky suggested that only cinema was capable of imprinting time in this way; he did not venture to expand his theory to other media. However, he did work in other media, beginning with his productions for radio (Faulkner’s Turnabout in 1965) and in the theatre (Hamlet in 1977). His interest in media other than the feature film was intensified after Stalker, when he also began to make more frequent public appearances, where he discussed his next film projects as distant desiderata: ‘In principle I do not really feel like making films. Of course I will; I can’t avoid it … But right now I don’t want to. Perhaps I’m tired of the cinema.’

Fig.3

Andrei Tarkovsky

Mirror 1975

Ignat picks up the spilt coins

© The Estate of Andrei Tarkovsky

Fig.4

Andrei Tarkovsky

Stalker 1979

Coins amidst the submerged refuse

© The Estate of Andrei Tarkovsky

Tarkovsky’s fatigue was banished by a journey in space which gave rise to a new conception, the film Nostalghia (1983) based on a screenplay Tarkovsky co-authored with Tonino Guerra. The moment of the film’s conception is captured in Tarkovsky’s 16 mm short Time of Travel (1979) which is unique in Tarkovsky’s oeuvre for its jarringly discontinuous montage of image and sound. After inspecting the inlaid floor of one ancient church the camera shows scenery from the window of a car driving in the country; there is a loud screech, as if before an accident, but the image changes to a shot of a smiling, relaxed Tarkovsky, and then to foliage and an empty cage in Guerra’s back garden. As the men share a meal of seafood and pasta with unidentified men in the street the soundtrack shifts from traffic to sounds of eating and the clink of bottles, and then to the steps of a child shown carrying a balloon. At times the sound cuts out completely. Time of Travel is a moment of reflection and conception – a moment of spatial investigation – deprived of any duration in time. It presents the elements out of which a film will emerge, but is completely removed from the narrative and pictorial continuity that will bring them to life. Perhaps that is the point of Tarkovsky’s rather cloying complaints about the pretty tourist sites they have seen so far. Guerra comments that Tarkovsky had to see all of these places in order to know how to shoot his character in generic ‘Italian’ space, that is, in the languid flows of ‘neutral’ Italian time. Indeed, Tarkovsky is heard inquiring of a bell-ringer at Bagno Vignoni whether he cooks his own food. He is seeking a fictional form that will not be merely an imaginary construction, but will withstand exposure to the concrete conditions of its realisation.

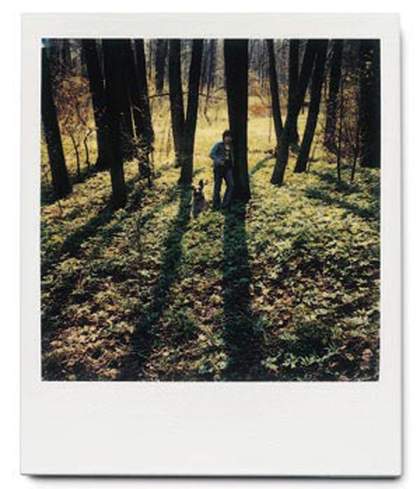

Fig.5

Andrei Tarkovsky

Polaroid photograph

© Andrei Tarkovsky

Tarkovsky’s growing interest in alternative media is evident in his Polaroid photography (fig.5), recently exhibited and collected.13 With its temporal inflexibility, restricted focus and artificial colour, the shortcomings of the Polaroid camera would seem to be antithetical to Tarkovsky’s 35 mm cinema; the same goes for its virtues, notably its portability and spontaneity, which had not been hallmarks of Tarkovsky’s cinematic art. By dint of their uniform size, sterile white borders and inherent instability, Polaroid prints challenge the exalted estimation of the art object in Tarkovsky’s writings; one sees Tarkovsky struggling to adapt to the constraints of the new medium and exulting in the new vision of his familiar world. Tarkovsky’s Polaroids are notably different from the photographs of Chris Marker, for instance, whose emphasis always is on the shared regard between the camera and human (and sometimes animal) faces, which express an irretrievable moment, ‘the moment of certainty’.14 Tarkovsky, by contrast, photographed landscapes and street scenes in which nothing decisive seems to be occurring at all. Human figures are shown in classical poses, which seen through the optics of the Polaroid make them reminiscent of Gerhard Richter’s gauzy rendition of paintings in his Annunciation after Titian or of photographs in or A Girl Reading (fig.6).

Gerhard Richter

Elizabeth I (1966)

Tate

As Boris Groys has commented, the world in Tarkovsky’s Polaroids ‘is already an image in a kind of historical succession that relates to something that he has seen before, whose construction he already knows about’.15 A notoriously unstable medium, the Polaroid is not a stable image of a fleeting reality but a fleeting, degradable image of a reality that persists, if anything made less transparent, less communicable for having imprinted in this way. Together Time of Travel and the Polaroids provide an approximate sense of how Tarkovsky might have adopted the medium of video. Both bring to the foreground the figure of the artist who makes split-second decisions and then arranges the image into a patently discontinuous sequence, forcing the viewer to participate actively in the construction of a continuous narrative.

That Tarkovsky remained an artist of the cinema is confirmed, if only in the negative, by his production of Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov at the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden in 1983. As in his production of Hamlet, Tarkovsky discovered new pressures in the ephemeral medium of opera performance, where the image is inherently unstable and the pleasure of the viewer derives from elements such as voice and gesture. Chris Marker has confessed that, after watching Tarkovsky’s Boris he stole his opera glasses ‘in the hope that one day they would give me back the images they have seen’.16 Marker seems to share the suspicion that, whatever the medium in which he worked, Tarkovsky remained attached to the cinematic image, a medium where he was, so to speak, in his element – the element of time. In his 35 mm films Tarkovsky was able to orchestrate each shot with an almost obsessive attention to detail, which lent the image an unmistakably minted quality and rendered the screen space a sensate membrane of material forces, eliciting from the viewer not only intellectual participation but also physical presence. In this sense Tarkovsky belongs not only to the genealogy of poetic cinema but also to the experimental cinema typified by Stan Brakhage. For both artists cinema is authentic not because of what it represents, but because of what it enables in the viewer as a project. As poet Robert Kelly has written apropos of Brakhage, such a film ‘silences story so that we can happen’.17 Taking a similarly broad view of Tarkovsky’s cinema aesthetic allows us to posit why it has proven of such relevance for artists in various media who privilege the very problem – the mystery – of mediation.

The lateral view

The position which I am suggesting for Tarkovsky’s films in the history of the cinema is akin to that held by Man Ray’s Rayographs in the history of photography. In Paris in 1921 Man Ray happened upon the simple technique of laying objects on top of photo-sensitive paper beneath an intense light-source: ‘I remembered when I was a boy, placing fern leaves in a printing frame with proof paper, exposing it to sunlight, and obtaining a white negative of the leaves. This was the same idea, but with an added three-dimensional quality and tone graduation.’18 To be sure, Man Ray was far from the first to utilise this technique, which is most firmly associated with William Henry Fox Talbot in 1834–5 but might also have been the earliest form of photography in the late eighteenth century. Nonetheless, as the artist Jan Svenungsson has remarked, ‘it was not until Man Ray started to develop the technique in late 1921, and gave it a name, that this type of picture became a concept’.19 On Tristan Tzara’s advice Man Ray included Rayographs in his experimental short film La Retour à la raison (1923), which would appear to be the first overt recognition of the cinema as imprint.20 André Breton, leader of the surrealist movement, saw Man Ray’s oeuvre as eliding the difference between glamorous fashion portraits, staged compositions and abstract exposures, baring the photographic medium: ‘For those who are expert enough to navigate the ship of photography safely through the bewildering eddies of images, there is the whole of life to recapture, as if one were running a film backwards, as if one were to be confronted suddenly by an ideal camera in front of which to pose Napoleon, after discovering his imprint on certain objects.’21 The reluctance of the artist to interpolate himself between the object and the element of light allows the medium itself to emerge as a condition for the possibility of both object and element. The Rayograph is, in a sense, the purest photograph, because it renders nothing other than the element of light.

Tarkovsky may not have run his camera backwards, but he did run it notoriously slowly and carefully, becoming the first to turn long-take cinema into a concept. The suspension of forward movement through the halting narrative and meditative shots forces the viewer to confront the medium as the very matter of representation. One sees a similar tendency in Chris Marker, most notably in the friction between continuous sound and discontinuous image in La Jetée (1962). For Marker this residue potential of the image is exemplified in the Zone, the indeterminate location of the action in Tarkovsky’s film Stalker, which relinquishes all ‘pretexts and rationales’ and becomes localised as the screen where a debased world regains its material texture. In Sans Soleil (1983) Marker features the Japanese artist Hayao Yamaneko who digitalised photographs on a computer program he called the Zone. According to Marker’s commentary, Hayao ‘claims that electronic texture is the only one that can deal with sentiment, memory and imagination’.22 It would be a mistake to fetishise any particular technology; after all Hayao was working in the Pacman era of computer graphics and Marker’s own media experiment Immemory (1998) now requires an out of date operating system to be viewed. Like Tarkovsky’s Polaroids, these images are inscribed with their obsolescence at their very moment of production. The point is the peculiar suspension of the image that occurs in its re-mediation, which destroys its semiotic referentiality, leaving only an irreducible materiality at the basis of the disintegrated image. Marker comments:

Memories must make do with their delirium, with their drift. A moment stopped would burn like a flame of film blocked before the furnace of the projector. Madness protects, as fever does. I envy Hayao and his Zone. He plays with the signs of his memory. He pins them down and decorates them like insects that would have flown beyond Time and which he could contemplate from a point outside of Time – the only eternity we have left.23

In recent installations Marker himself has digitally manipulated stills from video ‘in order to extract meaningful images from the inordinate flow of video and television’.24 This life-long effort culminated in Marker’s CD-ROM Immemory, which is divided into Tarkovskian ‘zones’ navigated by the computer operator ‘without pretexts or rationales’.25 In Timothy Murray’s words, the ‘interactive deterritorialisation of narrative form and readerly confidence’ forces the spectator actively to compose the image.26 For Murray Immemory marks the passage of cinema from debased projection onto the electrifying membrane of the digital screen’.27

As if following Marker’s suggestion, artists in new media seem to have identified vividly with Tarkovsky’s image of the lone explorer in a zone of indeterminate visual and sonic experiences. The Web Stalker (aka I/O/D4, 1997) was an alternative browser invented by a collective of British artists as an immanent critique of the internet.28 S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl is also the name of a series of video games originating in Russia but with worldwide appeal. However Tarkovsky’s influence is most palpable not in the appropriation of new media per se, but in artists who, on the continually growing and changing imagescape of contemporary life, continue the interrogation of media as the locus of a new materiality – the materiality of mediation.

Tarkovsky in contemporary art

The recent works in which I see Tarkovsky’s presence must be carefully distinguished from the adulatory homages with which Tarkovsky has been amply rewarded. In film one can name the work of Donatella Baglivo or Sokurov’s Moscow Elegy (1987). In music Tarkovsky has been a particular favourite of the ECM stable of artists, including Jan Garbarek and Francois Couturier. As has been widely remarked, and as James Quandt has documented in detail, there is an unfortunate tendency for European filmmakers to imitate Tarkovsky’s style.29 The most egregious case are the derivative films of Andrei Zviagintsev, but even such major artists as Béla Tarr prove susceptible to accusations of turning Tarkovsky’s long-take aesthetic into a cliché.

Quite different is the appropriation of Tarkovsky in Psi-Girls (1999), where Susan Hiller includes an excerpt from Stalker in a simultaneous display of five episodes from contemporary film featuring young girls with telepathic powers.

Fig.7

Susan Hiller

Psi-Girls 1999

Commissioned by Delfina Gallery/Millwall Productions, London

Tate © Susan Hiller; Courtesy Timothy Taylor Gallery, London

Of more interest here are works which, instead of replicating Tarkovsky’s art, release its hitherto dormant potentialities. Such an oblique homage is David Bate’s Zone (2001), a series of colour photographs taken in Estonia, where Stalker was shot. Bate’s Gathering Crowd captures the way that the surface of Tarkovsky’s screen uses subtle variations in texture and colour to puzzle our vision and elicit from us a more assertive posture of viewing. The image bears more than a passing resemblance to the abstractions of Gerhard Richter, in which studied hyper-realism yields to an intense, attentive study of the depths of painted surfaces (figs.8, 9).

Fig.8

David Bate

Gathering Crowd from ZONE series, 2001–5

C-Type photograph 80 x 120 cm

© David Bate

Another intensification of Tarkovsky’s cinematic Zone is Jeremy Millar’s film Ajapeegel (2008), shot on the very location of Stalker, a disused hydroelectric power plant outside Tallinn in Estonia (fig.10).

Fig.10

Jeremy Millar

Ajapeegel 2005

© Courtesy Jeremy Millar

In an oblique voiceover reminiscent of Marker, the narrator tells of how the original conception of shooting the stag parties of British men in Tallinn became the study of surfaces that conditioned Tarkovsky’s gaze and retain the memory of his investigation into the place. It is this moment of extreme suspension that Millar captures. Like the artists Tacita Dean and Hannah Collins, Millar thematises the long duration dolly-shot as a vital technology of vision that is capable of capturing not only event but also temporal ‘atmosphere’ (as Millar’s narrator calls it).30 As in some of Bill Viola’s works, these films are shot on 35 mm (or, more rarely, 16 mm) for the higher image resolution, and transferred to digital video for museum projection. The attachment of these artists to the medium of film – elegised in Tacita Dean’s 16 mm film Kodak (2006) – renders it as the central ruin of post-modernity, a lost utopia where once a future was possible. The effect is akin to the way that Tarkovsky used cinematic anamorphism to explore alternative temporalities, what might be termed anachrony. It is in watching these films that one comes closest to a kind of pensive contemplation. This is not a dream of escaping to a real world outside of the apparatus but a recognition that the closest thing to immediacy is when mediation itself becomes the object of representation.

Tarkovsky and video installation art

Such more or less overt appropriations of Tarkovsky call attention to less conspicuous parallels between Tarkovsky and the aesthetics of contemporary video art, most notably the long take. The long take has been at the centre of the shift from film to video, a shift that has taken place as a gradual progression from Warhol’s Sleep to Fischli and WeissDavid Weiss’s Der Lauf der Dinge and Bill Viola’s work. In part this is tied to the specific technologies. As Helmut Friedel has noted, in video the ‘visual documentation of long periods of time became possible, not as a collage of edited film footage, but as a genuine record of the passage of time’.31 Moreover, the change from projection to installation has, if anything only increased the attention paid to the time-form. It has also been a result of narrative experimentation. As the curator Susanne Gaensheimer writes, if ‘the readability of the film’s narrative is eliminated, making an interpretation in the traditional sense impossible, then its semiotic structure is altered to new, different meaning constructs’.32 Directors who have made the transition to video art, from Chantal Akerman to Atom Egoyan, have proved themselves adept at shifting the locus of meaning-production from the screen to the viewer who encounters his or her own anxieties in the struggle to make sense of the projection. In the dialectical tension that marked the classical regime of representation, video art marks the final victory of suspension over suspense. In the words of the cinema historian Dominique Païni, ‘From images that only exist because they are made of light [arise] therefore images that are made of time’.33 Indeed, Bill Viola himself has identified time as the ‘essence’ of video art, which can show ‘gradual permutation in the continuous, inexorable progression toward or away from’ an event.34

There is, however, no reason to limit the analogy between Tarkovsky and contemporary searchings to the element of time and the technique of the long take. Applying to Tarkovsky what Jacques Rancière has asserted regarding Godard, one can say that his films present ‘the aesthetic dream: the dream of “free” presence stripped of the links of discourse, narration, resemblance; stripped, indeed, of any relation to anything else except the pure sensory power that calls it to presence’.35 Rancière identifies this phenomenon in cinema as a new symbolist aesthetic, one that is currently blossoming in video installation art which experiments with new forms of projection in order to modulate the physical relationship between work and spectator: ‘the installation allows one to conjugate in visible space, by manifest processes, the circularities and fragmentations that books and films must treat within the logic of a space that is more or less subject to the linearity of time’.36 Many of the artists mentioned hitherto, from Marker to Millar, have situated video work in carefully configured spaces of experience. The rediscovery of Tarkovsky as artist simply opens up a parallel line of ancestry for the aesthetics of video art, leading back through poetic cinema to Russian symbolism.37

There are distinct parallels between Tarkovsky’s films and Mark Wallinger’s Via Dolorosa (2002), a video projection of excerpts from Franco Zeffirelli’s film Jesus of Nazareth (1977) with a large central portion of the screen blacked out (fig.11).

Fig.11

Mark Wallinger

Via Dolorosa 2002

Courtesy Anthony Reynolds Gallery © Mark Wallinger

Unlike the Black Square of the Russian constructivist painter Malevich, overtly referenced by Wallinger, Via Dolorosa retains the promise of representation even as it denies the viewer easy visual gratification, thereby dramatising the role of narrative (whether inherent or external to the work) in filling in the empty spaces in the representation. Continuity is promised even as it is withheld; indeed, the withholding of visual pleasure promises continuity above and beyond the merely visible. Wallinger thus allows for a re-examination of Godard’s and Rancière’s equation of cinema projection and Veronica’s veil. The direct imprint of reality is not only given at several degrees of removal; to retrieve it requires negating the very projection that makes it visible in lieu of – in hope of – a purer visibility.

The helpfulness of including Tarkovsky in the history of this new art is underscored by the work of Douglas Gordon. Gordon first became widely known for his installation 24 Hour Psycho (1993), in which Hitchcock’s film is projected on a 3 x 4 metre screen hung at about head height diagonally across a room. The spectator is invited to walk around the image, viewing it both from the front and back, encountering it as a material barrier. Crucially, the video with the film is drastically slowed, stretching the 110 minutes of the original film to the length of an entire day, with the image changing approximately every two seconds. According to new-media theorist Mark Hansen, the suspension of Hitchcock’s narrative ‘strips the work of representational “content” […] such that whatever it is that can be said to constitute the content of the work can be generated only in and through the viewer’s corporeal, affective experience, as a quasi-autonomous creation’.38 Hansen argues that, by withholding representation and rendering the spectator’s body as the compositional centre, recent video art redefines the image, which ‘now demarcates the very process through which the body […] gives form or in-forms information’.39 Gordon’s interrogation of the screen is the culmination of the old symbolist dream of dismantling the ramp that divides the audience from the stage and relegates the spectator to a purely passive role.

While Hansen insists that this interactivity is a distinct quality of the new digital media, Tarkovsky’s and Marker’s films demonstrate its importance also in older media where the suspension of narrative flow makes the spectator (or reader) the centre of composition, the locus where the elements are re-constituted in their materiality. To my mind, the key distinction between Tarkovsky and Gordon is not so much the medium itself (that is, film versus digital video) but in the form of projection. Gordon’s screen is qualitatively different from that of Tarkovsky or Marker, making the viewer’s engagement with Gordon’s work both more corporeal and more ephemeral. However the underlying relationship between suspense and suspension in the two artists (and, more broadly, in poetic cinema and contemporary video art) differs only in degree, not in kind. Critics have disagreed whether Gordon’s work completely dismantles the aesthetic regime of representation; in part the question hinges on how reliant Gordon’s work remains on the viewer’s knowledge of Hitchcock’s original.40 It is probably part of Gordon’s intention to dramatise the tenuous relationship between our experience of images and our vast image-memory, as when Marker, in Immemory (2002), warns the viewer that it is hopeless to continue into one of its zones unless one knows Hitchcock’s Vertigo by heart. In each case both the screen and the narrative are at once conditions of projection and barriers to understanding. The work suspends its own forward motion, making time physically palpable along with the image that we confront. Albeit in a more dramatic, even theatrical manner, Gordon’s video installations continue the task of cinema as formulated by the philosopher Gilles Deleuze: ‘The cinema must film, not the world, but belief in this world, our only link’.41

Another illustration of the foregoing is Gordon’s 30 seconds text (1998), a quite simple installation consisting of a room of four black walls, one of which bears a text in white print, lit by a single naked light bulb for about thirty seconds at a time. During the brief time of illumination the viewer reads through an account of a doctor who tested the lingering consciousness of a man’s head after it was severed from his body by a guillotine. The doctor concludes that the man retained some awareness for twenty-five or thirty seconds, which – a short postscript informs the viewer – is the approximate amount of time it should have taken us to read the text. The story attracts the viewer’s interest and participation, but the postscript immediately undercuts the viewer’s detached gaze. The time we have been reading is coterminous with the time of a death we have just witnessed. Moreover, the onset of darkness as we complete the text subjects the viewer to an almost inevitable flash of anxiety and vulnerability, as we realise that we are both interrogators of the dead head and potential victims of decapitation. One can develop out of this installation various ideological messages, including opposition to capital punishment and a commentary on the voyeurism of museums. However, most intensely, it manifests the materiality of the image tenuously joining body to mind in a single consciousness.

Douglas Gordon’s installation Plato’s Cave (2006) consists of a dark room with a lit fireplace that projected on a blank wall the shadows of its viewers. The spectator of this projection is no longer a spectator; the location no longer a mere location; the work is not object; rather the world is a manifold of pure visibility. In its elegant and elemental simplicity, this installation retrospectively illumines the significance of Tarkovsky’s metaphysical cinema as an event in the global history of the image.