Sickert’s painting, Brighton Pierrots, 1915 (fig.1), is a tender, evocative representation of a seaside vaudeville troupe performing their act on a wooden stage erected on the seafront at Brighton. The artist painted two versions of the subject. The first, now at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford was bought by Morton Sands, the brother of Sickert’s great friend and correspondent, Ethel Sands (fig.2). The second, in Tate’s collection, was commissioned by the eminent barrister William Jowitt and his wife after they had seen the first painting in Sickert’s studio in London. The two versions are practically identical apart from small variations in composition and appearance. The short cane held by the foremost pierrot and the streaks of light emanating from one of the overhanging gas lights are absent in Tate’s painting which is also rather brighter and more acidic in colour. In addition, Tate’s painting includes visible traces of a figure standing behind the pink pierrette at the piano which Sickert has partially, but not entirely rubbed out. It is the second version which is generally accepted to be aesthetically rather more effective and is referred to here throughout.

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Brighton Pierrots 1915

Oil on canvas

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Sickert described Brighton Pierrots as ‘a bit of all right’,1 but other viewers were rather more eloquent in their praise. The critic of the Daily Telegraph saw one of the two paintings exhibited at the Carfax Gallery in 1916 and wrote:

Here we have a company of players in more or less Italian comedy (commedia dell’arte ) costumes, performing on a stage set up in the open, with a background of Brighton houses of the more old-fashioned type. The charm of the picture is in the conflict between the luminous air of evening and the artificial lights, under which these poor abraded butterflies of the stage appear half-immaterialised, and with a glamour that is theirs but for this short moment.2

Both as an artist and as a personality Sickert is recognised as a vital conduit of information and ideas between Paris and London in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. His paintings reveal his familiarity with contemporary French art, particularly Degas, but also reflect an awareness of trends prevalent within European culture in general. His work also represents a visual record of popularist English urban entertainment at the turn of the century, an arena not previously explored by any other British artist. This essay discusses the social-historical context of seaside pierrot groups in England and the related European traditions of the Italian commedia dell’arte and French pantomime.

Throughout his life Sickert had been in the habit of spending his summers in France, usually in the coastal holiday resort of Dieppe. In 1915, however, for the first time in over seventeen years, the artist was denied access to his favourite town. The ongoing hostilities of the First World War forced him to seek a new destination for his summer vacation, somewhere which had to combine rest and relaxation with interesting and stimulating subjects to paint. An obvious choice was the Sussex seaside town of Brighton, a place which shared so many characteristics with his beloved Dieppe: fresh air and bathing, elegant lawns and promenades, and a wide variety of entertainments, even for someone used to the extensive diversions of London. An added incentive was the generous hospitality of his friend and patron, Walter Taylor (1860–1943), a wealthy man of leisure and amateur watercolour painter who had lived in Brighton since 1910. Sickert described Taylor as ‘a charming host’,3 providing his guests with congenial company and good food in the ‘friendly atmosphere of his house’.4 Taylor lived at 4 Bedford Square, a Regency town house with a sea view opposite the West Pier. Using Taylor’s house as a base Sickert was able to avail himself of Brighton’s numerous leisure facilities including the Municipal Art Gallery, the Baths and the Aquarium where the artist considered making drawings of the ‘theatrical light & shade of the tanks’.5 His favourite spectacle, however, was the ‘delightful and interesting’ pierrot theatre found performing daily on the seafront which he claimed to have visited every night for five weeks during the summer of 1915.6 The resulting painting, Brighton Pierrots, was completed from sketches taken on the spot.

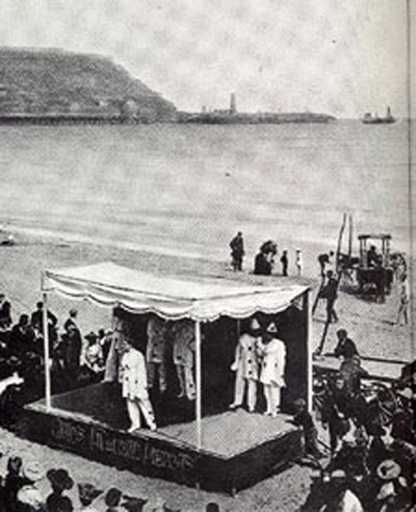

Fig.3

Pierrots on the beach, c.1910

Photograph

Published in Pertwee’s Promenades and Pierrots: One Hundred Years of Seaside Entertainment, Newton Abbot, Devon 1979, p.86

Pierrot groups first appeared in Britain’s coastal resorts during the 1890s after being instituted by a singer and banjoist, Clifford Essex.7 He established the first pierrot group after a visit to France in 1891, having been struck with the appearance of traditional pierrots of French pantomime. They became an established feature of seaside entertainment until the Second World War (fig.3). Each troupe occupied its own pitch and performed on a portable wooden stage, usually erected directly on the beach.8 Members of the audience seated in deck-chairs were asked to pay a nominal fee to watch the act. Although pierrot routines shared some common features with those of the urban music hall such as comic sketches, dancing and popular songs, their material tended to be less risqué, offering instead hearty family entertainment. A contemporary fictional story by Paul Herring, The Pierrots on the Pier, Published in 1914 by ‘Hulton’s 3d novels’ offers a description of a typical pierrot show:

The pierhead at Seathorpe was crowded, all available deck chairs and pier seats were claimed, and groups of people were standing, making an extensive awning of sunshades and straw hats in the blaze of morning sunshine … Three white figures with banjo and mandoline gathered near the piano. The marionettes bowed to the company and Morrice Grey seated himself at the piano. As an overture, the minstrels gave a selection from the Pearl Girl [a popular musical by Howard Talbot, written in 1913]. Then they commenced their original programme. To the tinkle of his own mandoline Dick related a dainty romance of Pierrot in difficulties … Morrice Grey varied the programme by wonderfully clever imitations of music hall celebrities and famous actors … Afterwards there were rag-time songs, selections from the latest musical comedies, a tango medley and a costume recital … and a topical song of pantomime pattern with verses touching on questions of the hour, and a jolly chorus, “Although the Deutsches Kaiser may bluster and despise her, / Brittania’ll take the Germans down a peg.”9

Early troupes wore costumes derived from the pierrot character of French pantomime, typically loose pantaloons and tunics with ruffles around the neck, big black buttons or pom poms and a conical shaped hat. At the beginning of the twentieth century it became common for pierrots to incorporate contemporary clothes into the second half of their act such as evening dress with top hat, or blazers and boaters.10 The troupe in Sickert’s painting exhibit both fashions. Traditional costume is worn by a pierrot in green sitting at the back of the stage and a pierrette in a pink dress seated at the piano. By contrast, the two performers foremost on the stage wear modern red suits and straw boater hats. Visible through the legs of one of these men is another figure carrying what looks like a tray. They are possibly selling refreshments but are more probably the troupe’s ‘bottler’, a member of the act who circulated amongst the standing onlookers encouraging tips with easy banter and jokes.11

Sickert’s interest in the pierrot theatre derived from his love of low-brow popular entertainment which had found full expression in his series of paintings of London music halls. As the art historian Anna Gruetzner Robins has previously shown, Sickert tended to avoid the classier, more respectable mainstream halls of the capital in favour of the seedier venues such as the Bedford and Gatti’s Hungerford Palace of Varieties.12 Similarly in Brighton it was typical of his tastes that he inclined towards the cheaper, more modest or low-key entertainments. Even in wartime the summer season in Brighton offered a bewildering array of pleasures. During the August Bank holiday of 1915, when Sickert was in town, the newspapers reported record numbers of tourists flocking to take advantage of the glorious summer weather. The visitors included some five thousand workers from the Woolwich Arsenal taking their first vacation since the outbreak of war.13 Daily entertainments for which they were encouraged to part with their money included West-End plays and musicals at the Palace Pier, the West Pier and the Theatre Royal, classical concerts by the Municipal Orchestra in the Aquarium Winter Gardens and a variety show at the Hippodrome. There was also a visit by Stella Carol, the ‘Human Lark’, a showing of the film Brave Little Belgium Before and During the War, and a lecture by Hilaire Belloc on ‘The War: The Present Position and the Recent Fighting’ at Hove Town Hall.14

A particular treat during the middle of August 1915 was an appearance at the West Pier theatre by the Follies, one of the most famous and successful vaudeville groups of the period. The Follies toured the country and, as well as appearing in London, they bore the distinction of having been invited to perform for the Royal Family.15 They offered a full and varied programme of humorous and picturesque songs, dancing in pierrot costumes, music hall burlesque, grand opera and a pageant of historical characters.16 The Brighton Herald reported: ‘If the whole of the audience at the West Pier this week are not rolling in their seats with laughter, the only explanation is that they are packed so tightly there is no room to roll … There are occasions when the audiences laugh so much that the Follies, one imagines, can scarcely hear their own jokes’.17 The standard of performance of a professional troupe like the Follies must be supposed to have been a great deal higher than that offered by some of the local pierrot companies operating on the front at Brighton. However, it was typical of Sickert’s idiosyncratic low-brow tastes that he eschewed the more sophisticated shows in favour of something a little less polished. Richard Shone has suggested that the pierrots depicted by Sickert could have been a company known as the ‘Highwaymen’, a group run by a local entertainer, Jack Sheppard, which had been operating in Brighton since the early 1900s.18 Contemporary photographs shows that the Highwaymen were a troupe of between six and eight male and female artistes (fig.4).19 They were later famous for launching the career of Max Miller who was their bottler from 1919. They had an established alfresco pitch on the beach opposite the Brighton Metropole Hotel, within very easy walking distance from the West Pier and Walter Taylor’s house in Bedford Square.20

Fig.4

Jack Sheppard’s Entertainers, 1920

Photograph

Published in Pertwee’s Promenades and Pierrots: One Hundred Years of Seaside Entertainment, Newton Abbot, Devon 1979, p.40

The progenitor of the seaside pierrot troupe was the European tradition of the commedia dell’arte as performed in Italian fairground sideshows, circuses and theatres since the sixteenth century. The commedia was characterised by improvised performance based around set scenarios and popular characters.21 The routines incorporated singing, dance, music and acrobatics, comedy and drama, performed by itinerant groups on makeshift stages. They were particularly popular for their subversive and discerning insights on society, human foibles and universal themes such as love, jealousy and old age. One of the stock characters to emerge from the commedia tradition was that of Pedrolino, a zanni, or peasant figure, who wore loose fitting white trousers and a smock. Generally hopelessly in love with a beautiful but fickle woman he had a sharp wit and a childlike capacity for laughter and tears, and was often an unwitting victim of the tricks of his fellows.22

During the eighteenth century the genre of the commedia dell’arte moved with its travelling performers through Europe and merged with a new art form, that of silent French pantomime. Many of the characters also made the transition becoming new, but recognisable reincarnations, for example, Arlecchino became the mad trickster Harlequin, identified by his colourful, diamond patterned suit. The foolish Pedrolino, sometimes also called Piero (Little Peter), gradually evolved into the French character of Pierrot, an innocent love-sick dreamer and one of the most important and recognisable figures in alternative theatre.23 The symbolism and aestheticism of the character became so well established that Pierrot made the transition from low theatrical performance to high visual art. Jean Antoine-Watteau (1684–1721), for example, depicted the character in several paintings and helped to crystallise Pierrot’s attributed psychological traits of sadness, foolishness and sensibility.24 In Pierrot, also called Gilles, circa 1718–19 (Louvre), the protagonist, dressed in a baggy white tunic and ruff, stands in a stiff upright stance. His arms are held awkwardly straight at his sides like an immobilised puppet, yet his expression is full of feeling. Sacheverell Sitwell (1897–1988), the poet, critic and commedia enthusiast, described him as a ‘young man presented with difficult situations, who is dumbfounded by them and yet solves them by his kind of natural magic. A strong aura of poetry attaches to him enhanced by his diffidence and awkwardness which are at the same time his acrobatic ease.’25 The creation of the definitive pierrot look is accredited to the Bohemian mime artist Jean-Gaspard Deburau (1796–1846) who performed his silent act in Paris in the early nineteenth century.26 In his white smock and pantaloons with a face whitened with flour and a black skull cap he established Pierrot as a lovesick, silently suffering clown. Essentially a comic character provoking the audience to laughter, Pierrot simultaneously incites sympathy and pity with his hapless antics, lovelorn countenance and melancholic air.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries this dual role of the tragic comedian assumed a new visibility and intellectual resonance in modernist culture. The themes and motifs of the Italian commedia dell’arte, and its French or English ‘Harlequinade’ equivalent, were extremely influential to a number of modernist artists, writers and composers who were drawn to its subversive nature and irreverent spirit.27 Themes and symbols drawn from this vulgar, improvisational world began to taken up and absorbed into high culture, in the poetry of Charles Baudelaire and Jules Laforgue, in Arnold Schoenberg’s opera, Pierrot Lunaire of 1912, and in the work of visual artists such as Gustave Courbet, Gustave Doré, Honoré Daumier and even Henri Rousseau, an artist who usually worked outside of established cultural conventions.28 The commedia most famously inspired the magnificent costumes and quirky characters of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Carnaval, for example, first performed in 1910 was a ballet choreographed by Fokine to music by Robert Schumann which starred Nijinsky in the lead role of Harlequin. In 1911, the Ballets Russes performed Petruschka, a story about a puppet with a human heart, set to music by Stravinsky. Petruschka is a Russian manifestation of Pierrot who falls tragically in love with a ballerina and is eventually killed by a love rival. August Macke’s painting, Russian Ballet I, 1912 (fig.5), is based on one of the Ballets Russes commedia pieces. The viewer is positioned in the audience looking towards the stage to see Harlequin and Colombine flirtatiously dancing together. Beside them is Pierrot with his characteristic baggy costume, excluded from love and doomed to watch on the sidelines as a forlorn observer.

Fig.5

August Macke

Russian Ballet I 1912

Oil on canvas

Kunsthalle, Bremen

For modern artists, the pierrot represented a symbolic hero of sensibility and the figure was adopted as emblematic of the role of the artist in society. The character embodied the ability to employ parody and humour in the face of tragedy and was also identified with the artist’s struggle to both critique and remain complicit with the experience of modern life. Georges Rouault (1871–1958), for example, frequently portrayed himself as a pierrot or clown figure, exposing the tragedy behind the presented mask. James Ensor (1860–1949) and Emil Nolde (1867–1953) both exploited the melancholic aspects of the character. Picasso (1881–1973) particularly identified himself with the mercurial, elusive persona of Harlequin but Pierrot also crops up frequently in his work as an expressive, plaintive, vulnerable element.29 The appearance of the quaint white baggy figure also lent itself to artists as a decorative, aesthetic motif. Aubrey Beardsley, for example, supplied the cover illustration for Pierrot’s Library, a collection of stories by H. de Vere Stacpoole, published by John Lane in 1896.30 His pierrot is feminised and wistful, the elegant black and white lines recalling the graceful, measured movements of French pantomime. For some artists the pierrot became a symbol of contemplative meditation, for example, in Whistler’s etching, Pierrot, circa 1889, which depicts the back of a house reflected in the water of an Amsterdam canal.31 The image includes two figures in contemporary dress. The reference to ‘pierrot’ is not immediately obvious but surely relates to the whimsical day-dreamer leaning against a door post in the shadows. He appears to make direct eye contact with the viewer and his meditative gaze mirrors the viewer’s own act of looking and comprehension. Whistler’s friend and contemporary, Théodore Roussel (1847–1926) also recalled the reflective, introspective nature of the character in his portrait prints of Lady Archibald Campbell as Pierrot. She adopted the role for an outdoor performance of Theodore de Banville’s play, Le Baiser . In the drypoint etching Pierrot, Portrait of the Lady A.C., 1888, the subject wears the conical hat and ruff of the pierrot costume and her expression is one of dreamy contemplation.32

Sickert must have been well aware of the commedia dell’arte tradition and its recent renaissance in contemporary culture. As a young man he had initially pursued a career on the stage and his love of the theatre remained with him throughout his life. In 1911 the Ballets Russes appeared in London to widespread critical acclaim and, although there is no evidence that Sickert attended the performances, he was friendly with a number of Diaghilev’s London supporters such as the Sitwells and Lady Ottoline Morrell. He would certainly have known the prints of Beardsley, Whistler and Roussel, and as an assiduous gallery-goer was probably familiar with the work of his European contemporaries too. However, he is most likely to have come across the characters of the commedia during his sojourns in Venice where Pierrot, Harlequin and others made regular appearances in the city’s masquerades and the annual costumed extravaganza, carnavale. In around 1903 he painted a small panel entitled Venetian Stage Scene (private collection) for which Tate’s drawing, Pierrot and Woman Embracing is a preliminary study (fig.6). It has always previously been assumed that this drawing shows performers on a stage. Tate curator Robert Upstone has recently identified the precise location of the elaborate architectural doorway and columns in the background proving that it is in fact an observed glimpse of a romantic episode in a corner of Venice during carnavale. Pierrot in this instance is a romantic figure although the urgency with which he embraces his female companion and the passivity with which she receives his attentions hints at a tragic back-story to this liaison.

Walter Richard Sickert

Pierrot and Woman Embracing (c.1901)

Tate

Although the cheery bonhomie and popularist appeal of the seaside entertainers in Brighton Pierrots appears far removed from the dramatic masculine pierrot of Sickert’s Venetian painting, or Diaghilev’s ultra-modern aestheticism, Sickert is nevertheless engaging with both the traditional, and contemporary, power and pathos associated with the figure of the pierrot. In Brighton Pierrots he has deliberately created a complex and highly charged scene in which the pervasive mood is one of tension and melancholy. The artist has employed an oblique angle and a cropped composition derived from Degas with which to explore the disorientating, ambiguous effects of costume, artificial stage lighting and the contrived atmosphere of theatrical performance.33 Sickert’s arrangement of the figures on the stage undermines the perceived joviality of their performance, particularly the disjointed body of the man behind the central pole, a compositional component reminiscent of the post truncating Degas’s painting, Jockeys before the Start, 1878–9 (Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham). The man’s stance suggests that he is engaged in a slapstick comedy routine, kicking the backside of the hapless fellow in front. However, the disruptive line of the column in front makes his body appear disjointed and his kicking legs are seen as if bizarrely amputated from his body. This dislocation, combined with the acidic colouring and dramatic shaped shadows contribute to a disquieting sense of all not being well. Despite their comic, brightly coloured costumes the pierrots seem desultory and lack-lustre and the foremost performer, standing stiffly at the front of the stage, gazes out onto a depleted audience.

The context for the mood of the painting is explicit in the date, 1915. Both England and France were experiencing their second year of war and evidence of the ongoing conflict was an unavoidable presence in Brighton, perhaps more so than in many other English towns. The Brighton Gazette gamely reported an upbeat mood in the town but also printed the weekly casualty lists recording heavy losses from the Front. The use of the Brighton Pavilion as a hospital for wounded Indian soldiers afforded the locals the ‘strange spectacle of Red Cross vans occupied by parties of wounded Indians in loose blue robes and white turbans, and here and there a badly wounded soldier from the East being wheeled along the promenades in a hospital chair by a British orderly.’34 Lights were shaded early across the South coast for fear of nightly bombing raids and evening performances on the piers were suspended or commenced earlier than usual. On clear nights it was said that it was even possible to hear the sound of the guns in Flanders across the Channel. A possible reference to the war is made by the depleted numbers in the audience. Comparison of Brighton Pierrots with a preliminary sketch (fig.7) shows that Sickert has exaggerated the lack of numbers in the crowd in his finished scene. In the drawing there are considerably more people in attendance, standing along the back.

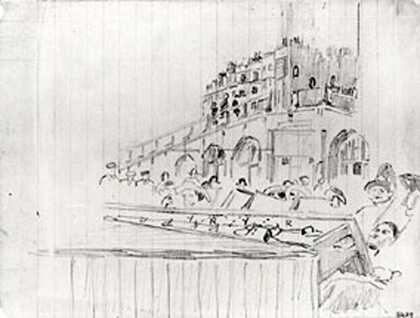

Fig.7

Walter Richard Sickert

Sketch for ‘Brighton Pierrots’ 1915

Pencil on paper

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Despite the war, however, it was business as usual for entertainers in Brighton and the pierrot troupe represents a poignantly brave, if perhaps pathetic, effort to inspire laughter and recall happier, more carefree days, at a time when the general populous was experiencing fear and loss on an unprecedented scale. Within such a context the figure of the pierrot becomes both a symbol of hope and sacrifice. Sickert may have derived the unusual side view from the compositional precedent of biblical ‘Ecce Homo’ subjects. Artists over the centuries have repeatedly shown Christ in profile being presented to the crowd by Pontius Pilate, mocked and rejected by the world (fig.8). In Brighton Pierrots, the foremost figure stands rigidly at the front of the stage, pictorially isolated from both the audience and the other performers, vulnerable to the scorn of the crowd, the tragic display of a potential self-sacrifice.35 The painting reflects both the shared widespread anxiety of wartime England and Sickert’s own dejected spirits at this time. At the age of fifty-five he was too old to enlist and expressed frustration at not being able to play an active role. In particular he was concerned for the fate of Dieppe, besieged since 1914. He felt personally oppressed and stifled by the war, writing, ‘What a stupid year 1915 will have been. One goes on in a kind of constipated dream’, and in another letter: ‘This war constipates my heart & pen’.36 However, the effect of the conflict on his painting ‘seems to have condensed my talent like pressure of air or water does at atmosphere.’ Brighton Pierrots can be seen as a creative release of wartime tensions.

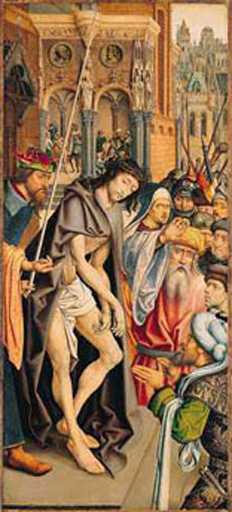

Fig.8

Master of the Bruges Passion Series

Christ Presented to the People c.1510

Oil on oak panel

National Gallery, London

Fig.9

Walter Richard Sickert

Sketch for ‘Brighton Pierrots' 1915

Pencil on paper

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Whilst the performers in contemporary dress recall the tradition of the pierrot as a symbol for comedy in the face of tragedy, the figures in traditional dress recollect the ability of the pierrot, and by association the artist, to remain cognisant of the gap between what is real and what is imagined. The arena of popular entertainment is employed as a space through which the truths of reality can be parodied and questioned. The imagined sounds of stage jollity are an ironic recreation of lost pleasures and well-being. Despite the prominent position of the red-suited duo, the principal focus for the viewer is actually the pierrette playing the piano. She is the pivotal figure placed at the vanishing point of the painting’s perspective. The vibrant pink of her traditional costume arrests the eye and she turns to stare at the viewer as if complicit in the artist’s exposure of the theatrical and artistic deception. She is also the one figure whom Sickert seems to have taken most pains to get right. There are two known extant compositional sketches related to the painting and one is devoted solely to her (fig.9). Her direct and knowing gaze becomes a visualisation of free will and conscious understanding, with the ability to see the tragedy behind the brittle mask of comedy.

In immortalising the subdued, transient pleasures of the ‘poor abraded butterflies’ of the Brighton Pierrots Sickert is seeking to engage with, and rise to the challenge of, a number of European dialogues: the stage paintings of nineteenth-century French artists such as Degas; the traditions of the commedia dell’arte and French pantomime; and the manipulation of those traditions with modernist culture at the beginning of the twentieth century. Sickert’s painting recalls the multiple associations of the traditional pierrot and reinvents that role within a contemporary British setting.