Fig.1

Répartition et emplacement des troupes de l’armée française (Troop Distribution and Positions of the French Army), 1905

Detail of Paris

National Archive, Kew TNA (PRO) WO 33/363

So far as numbers go, France has reached the zenith of her power as a military State, both absolutely and relatively; every man who reaches military age is now swept into the net of conscription, and practically all means of recruiting are used up. The Military Resources of France, 19051

In 1905, the year of this War Office Report on French military resources, Marcel Duchamp was drawn into the ‘net’ of military conscription that was intended to incorporate every able-bodied twenty-one year-old Frenchman into the national effort. Duchamp complied somewhat unwillingly but nevertheless managed to reduce his period of service by volunteering early and thus exploiting a law that allowed a reduction of time spent in the army.2 Consequently, Duchamp served only one year out of the possible three that he might have been eligible for, and from 1909 onwards he was occupied with an appeal to terminate his period of duty. It is clear that the authorities were reluctant to release trained soldiers: so Duchamp’s appeal was reviewed in several stages and was not necessarily resolved when the fighting finally ended in 1918. During this period of military uncertainty, military themes began to prevail in Duchamp’s work. Three years after his predicted second tour of duty, and when his appeal was underway, he made a journey to the Jura Mountains in the east of France. He subsequently reported on this journey in a series of four notes that he called the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ (fig.2).3 These were written as if preparing orders for a reconnaissance trip and have thematic echoes with communiqués initiating first moves in an occupation of territory. In this way, his notes can be considered as a military text in the context of a group of works by Duchamp that reflect on military subject matter.

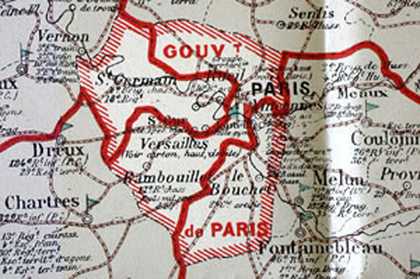

Fig.2

Répartition et emplacement des troupes de l’armée française (Troop Distribution and Positions of the French Army), 1905

The route of the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ has been schematically added in green

National Archive, Kew TNA (PRO) WO 33/363

This is an interpretation that changes the predominant view of Duchamp as disengaged from the events and responsibilities of his day. He becomes, instead, an anxious observer of the French military escalation leading to the war in August 1914. In the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ we begin to detect some of his concerns with the military ethos and infrastructure that followed from his conscription into the 39th Regiment of the Line in 1905. This essay looks at the effects on Duchamp of his military service as well as the conditions that influenced it and the actions that followed. Perhaps this study will help to shed light on the obscure references in the four notes that comprise the ‘Jura-Paris Road’, which, in turn, point to a nexus of concerns that continued to preoccupy him for many years.

Duchamp’s commentators have regularly cited the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ notes and the motor journey that preceded it, as being a catalyst for his imagination, although its importance within his work has, in spite of many insights, remained mysteriously obscure.4 Its appearance in bibliographies dealing with Duchamp’s critical year of 1912 has become a familiar aspect of the literature; and yet the notes continue to resist interpretation. 1912 was, of course, the year that Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase No.2, 1912 was rejected from the Salon des Indépendants. It was also the year of his developing friendship with Francis Picabia with whom he attended Raymond Roussel’s Impressions d’Afrique, a play dealing with themes of scientific improbability and exotic colonial encounter. Following this, Duchamp travelled to Munich, where in isolation he completed his erotic series of ‘Virgin’ and ‘Bride’ paintings and from where, lonely, isolated and sexually supercharged, he revealed his helpless infatuation for Gabrielle Buffet, Francis Picabia’s charismatic wife. Returning to Paris in October, he joined Picabia and the poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire on the automobile journey to the Jura to collect Gabrielle Buffet and return with her to Paris where, in the following weeks, he wrote his series of notes. Scholars have connected the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ notes with themes of eroticism, mechanisation and dimensional speculation and they all play an important part in any decoding of these notes. However, it seems that such connections can be made more compelling by a closer examination of the journey itself, which was inflected with particular discomforts and tensions. Although the title, ‘Jura-Paris Road’, defines the journey, the notes seem to deal with more than the descriptive possibilities and features of a route between the Jura and Paris. They describe a hierarchy of shifting interpersonal relationships in an unsettled environment of dimensional change. Behind these uncertainties lie more specific and topical preoccupations with territorial advantage that are encrypted into the language of deployment, colonial conquest, Christian mythology and hierarchical control. Beyond these are, perhaps, comments about the journey itself although these are by now more difficult to interpret.

Marcel Duchamp

Coffee Mill (1911)

Tate

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2025

The ‘Jura-Paris Road’ notes appear within the body of Duchamp’s work at the point where he had exhausted the practical applications of cubism and, indeed, the patience of its influential practitioners and theorists with whom he had been professionally connected. By the time of the ‘Jura-Paris Road’, his concerns with modulations of gender, epitomised in his Munich paintings, were no longer sustainable within the remit of orthodox cubism. After the journey to the Jura, Duchamp would re-address himself to a theme he had begun, provisionally, in 1911 with his small painting Coffee Mill (Tate T03250), where the ineluctable working of mechanical apparatus was subjectively considered (fig.3). He developed this interest with a series of mass-produced objects that eventually found their place within the automated logic of The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915–23 (fig.4).5 Thus his ‘toy-cannon’, ‘bayonet’ and ‘cuirassier’ as well as the other conscripted members of the ‘cemetery of uniforms’ that form the lower section of the Large Glass, are all conditional on Duchamp’s examination of military relationships. These began to emerge as a defining aspect of his inquiry after the commencement of his appeal in 1909. These ‘military’ works are drawn up for inspection, with the passing light of the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ enhancing their visibility.

Marcel Duchamp

The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915–23, reconstruction by Richard Hamilton 1965–6, lower panel remade 1985)

Tate

© Estate of Richard Hamilton and Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2025

The ‘Jura-Paris Road’, or at least the journey that inspired Duchamp’s narrative, is significant because it consolidated Duchamp’s friendship with Picabia and Gabrielle Buffet who, impatient with the constraining orthodoxies of cubism, and perhaps suspicious of its particular association with forms of nationalism were in the process of defining a creative process that would lead to less affiliated, less officially ‘French’ affinities.6 Picabia’s Spanish origins and his egotistical disposition made him impatient with the national and communitarian aspirations of the Puteaux cubists. Duchamp also felt the constraints of Puteaux sociability and looked elsewhere, probably towards Gabrielle Buffet, for inspiration. Both had developed working affiliations with Germany: Gabrielle Buffet had studied music in Berlin, and Duchamp, probably on her prompting, had spent the summer in Munich from where he had so recently returned. In a delicate distancing process of non-alignment with French painting he had circumvented some of its traditions by resorting to German oil paints, which he had been using for the past two years.

Although Duchamp, Apollinaire and Picabia were professionally connected and formed a common alliance in the world of Parisian art and no doubt had common projects to discuss, the journey would carry them away from the familiarity of these refinements and into an environment of exceptional physical discomfort where the realities of long-distance driving would eclipse their current enthusiasms for the human-machine metaphor. It was all very well for Apollinaire and Duchamp and subsequently Picabia to speculate on these convergences in their work but any notion that these thoughts would prevail in the course of a very cold and wet night-drive in an open car need to be viewed accordingly. Before the end of the journey both the car and its passengers would have lost much of the gleam of their metropolitan veneer. The disparity in outlook that would have been revealed in this testing period might well be exemplified by looking at their military service records. These show a considerable variance in attitudes, which would have made an increasingly obvious counterpoint to the military landscape that they were passing through.

Of the three men, Apollinaire, alone wanted to join up and had trouble in getting into the army at the outbreak of war. The two other men invested considerable time and energy in getting out of it. Apollinaire was registered as an alien and therefore had not been included in the general mobilisation in 1914. In fact, he had his application for the army refused. He was grudgingly conscripted into the artillery, and went into action in 1915, at which point he volunteered for the infantry where he was severely wounded, evacuated from the trenches in 1917, and then returned to Paris as a heroic non-combatant. Picabia, by comparison, stretched his influence to become a driver on the general staff. When this failed, his contacts secured him an overseas mission from where he absconded, spending the remainder of the war in New York, Spain and a Swiss sanatorium. Duchamp, as we have seen, was involved in a military appeal against his conscription, was then allowed to go to New York in 1915 and remained under military scrutiny until 1918. During the long trajectory of the drive between Paris, the Jura and then back to Paris again in October 1912, through the consecrated military landscape that north-eastern France had become, it would be surprising if these conflicting commitments were not exposed. By October 1912 it was clear that France and Germany were on a war footing and the appearance along the 380-mile journey of troop columns returning to barracks from their autumn exercises will have pointed up their distinctions and differences even further. Duchamp’s mood would soon be exemplified in this extract from a letter sent once the war had begun, to his friend Walter Pach, where he wrote:

There is talk of the ‘great spring attack’ supposed to be decisive. There’s a lot of confidence in the air with the first buds of spring. I remember only too well the same confidence in the month of August and it just seems to me that civilians are getting carried away.7

Duchamp then registered his doubts about the situation by secretly arranging his passage to America, despite the danger of submarines in the waters of the North Atlantic.8 In another letter to Walter Pach, six weeks later, he is even more explicit about his reasons for going: ‘I’m not going to New York’, he says, ‘I’m leaving France. That’s quite different.’9

Marcel Duchamp’s military models

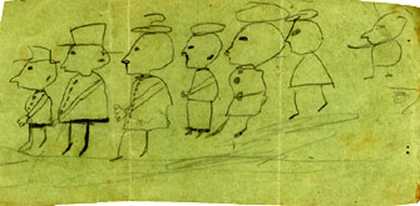

Fig.5

Marcel Duchamp

Parade: Seven People in Profile with Hats 1892

Private collection © Succession Marcel Duchamp 2006, ADAGP/ Paris, DACS, London

Fig.6

Marcel Duchamp

Soldier on a Horse 1894

Private collection © Succession Marcel Duchamp 2006, ADAGP/ Paris, DACS, London

As a boy, Marcel Duchamp made drawings and paintings of French soldiers, which are no doubt similar to the generic productions of other children whose imagination is caught by the appeal of the army and its paraphernalia (figs.5,6). The little paintings show a good eye for detail but one or two of these reveal puzzling anomalies that are perhaps genuine mistakes or perhaps show a more mischievous side. In one of them, the French colours are painted incorrectly so that they resemble an upside-down Dutch flag and another shows a cavalry officer in the absurd position of chasing his runaway horse (figs.7,8). Duchamp does not say if these paintings were motivated by the example of his two older brothers, Raymond and Gaston, who upon reaching twenty had been conscripted into the army while preparing for their artistic careers.10

Fig.7

Marcel Duchamp

French Flag, French Soldier 1894

Private collection © Succession Marcel Duchamp 2006, ADAGP/ Paris, DACS, London

Fig.8

Marcel Duchamp

Cavalry 1895

Private collection © Succession Marcel Duchamp 2006, ADAGP/ Paris, DACS, London

From his brothers, the young Duchamp would have absorbed the mystique enjoyed by the French army in the years before the Dreyfus scandal in 1894. Two years later, in spite of the Dreyfus affair and the consequent decline in the popularity of the army, Duchamp was photographed in a uniform where his martial appearance was augmented by a military képi and a campaign service medal (fig.9). These may have come from the wardrobes of either Gaston in the 21st Infantry, or Raymond who was serving in the 68th Artillery; it could have also come from their father who had been an officer in the war of 1870. Notwithstanding the provenance of the uniform, it is clear that Marcel Duchamp had direct connections with people of pronounced military ideals and opinions. Whether the costume was derived from his school uniform, or from the remnants of the children’s bataillons scolaires, or whether it was merely fancy dress, remain as questions to be answered, but so also does the question regarding Duchamp’s choice in wearing the costume.11 As a little boy Duchamp had been used to being dressed up by grown-ups and so it is possible that the family custom prevailed here,12 although as Jacques Villon’s sketch of his younger brother shows, Duchamp himself was not averse to posing as a soldier in the makeshift materials that came to hand (fig.10). Nevertheless, by being photographed in this way, Duchamp was sustaining a family commitment and endorsing the army at a time when it was coming under increasing public pressure.

Fig.9

Unknown photographer

Marcel Duchamp in uniform 1895

Photograph courtesy Association Marcel Duchamp

Fig.10

Jacques Villon

Marcel in Soldier’s Disguise c.1894–5

Private collection

Photograph courtesy Association Marcel Duchamp

Although the képi in the photograph appears too big for him it does not diminish his air of confidence. He relaxes, one hand casually in his pocket the other resting lightly on the handle of, what looks like a short sword. He conveys the easy command of an eight-year-old, interpreting the manner of older men. Raymond’s artillery sword would have been too awkward for him to wear, and so Marcel’s weapon was in all probability part of Gaston’s infantry equipment.13 The Lebel (1886) rifle supplied to infantry units came with its own épée-baïonette and this menacing, but actually rather impractical weapon was the one used here to bolster his military appearance. Almost twenty years later the standard épée-baïonette would appear in a second arrangement by Marcel Duchamp, when the distinctive blade appears as the locating spline for the revolving ‘Chocolate Grinder’, the central mechanism in the Large Glass (figs.11,12). The truncated blade is shorter than it should be, perhaps it has broken off, and so this rudimentary bricolage owes more to the soldier’s ability in adapting defective military hardware than it did to the memory of the martial aspirations of a play-acting boy at the time of Dreyfus.

Fig.11

Epée-baïonette (Sword-bayonet)

Illustration from Charles Lavauzelle, Manuel d’Infanterie à l’usage des sous-officiers, caporaux, et élèves caporaux (Infantry Manual for non-commissioned officers, corporals and lance corporals), 1912, Paris/Limoges 1915

Photography: K. Lyons

Fig.12

Marcel Duchamp

Chocolate Grinder No.1 1913

Philadelphia Museum of Art © Succession Marcel Duchamp 2006, ADAGP/ Paris, DACS, London

It is clear that by the time of Duchamp’s own conscription in 1905, this enthusiasm for the army had disappeared. The Dreyfus scandal had compromised the army’s reputation so badly that in spite of his upbringing and his early enthusiasm he went to exceptional lengths to avoid military service. Later, he would be celebrated for the detachment that would inform his methodology of indifference, but at seventeen, he brought a committed urgency to the task of evading conscription in the face of family expectation. The gulf that existed between Duchamp and the army is emphasised by the fact that, unlike his brothers, who were often photographed in uniform, no photographs survive of Marcel Duchamp in the infantry; the photographs that do exist show him in civilian clothes only (figs.13,14).14 In light of this distance from the army, it is perhaps unsurprising that a youthful drawing of a soldier with a studiously incorrect French flag should survive whereas photographs of the artist in uniform do not.

Fig.13

Unknown photographer

Jacques Villon in uniform 1906

Photograph courtesy Association Marcel Duchamp

Fig.14

Unknown photographer

Marcel Duchamp (front row) photographed with, from l. to r., Raymond Duchamp-Villon (in uniform), Yvonne Duchamp-Villon, Raymond’s mother-in-law and Gaby Villon, on the steps at Puteaux, Autumn 1914 or Spring 1915

Photograph courtesy J. Matisse Monnier © Musée des Beaux-Arts Rouen

Cubism and military tensions

The Dreyfus affair conditioned the military convictions of the two older brothers, but for Marcel Duchamp, a spell was broken here and a gradual separation occurred between them. This was not only evident in the relation to military service but in artistic matters as well. Their differences were underpinned by a diverging political vision. In the case of the brothers, this was epitomised in their commitment to cubism, which they were helping to promote into the main stream of Parisian culture: cubism had an international reputation, which was exported like many colonial enterprises of the day. Although tolerating foreign artists, the cubists kept the door firmly closed against foreign trends and its practice became an extension of a larger patriotic commitment.15 This caused problems between Duchamp and his brothers, which surfaced in 1912 when they were instrumental in rejecting his painting Nude Descending a Staircase No.2 from the Salon des Indépendants. The exhibition committee, for which the two brothers functioned as ideological enforcers, considered that the descending nude came too close to the contamination of influence from futurism. The references they detected compromised Duchamp’s cubist credentials, although he later protested that the distance between Italy and Paris was too great for tenable influences to occur.16

The law requiring Frenchmen to serve in the army created another sector of tension between them. Military service was generally accepted, particularly in nationalist circles, where it was held that the threat of German intervention made it incumbent on all French citizens to be ready for active service. Owing to the national disgrace over the loss of Alsace and Lorraine, war was inevitable and the election of Raymond Poincaré, a native of Lorraine to the Presidency in 1912, brought this closer. Duchamp’s reluctance to perform his military service and his general lack of enthusiasm for serving with the colours, either as a cubist painter in Paris or in the territorial defence of France has to be seen accordingly.

The extent to which this patriotic atmosphere prevailed in Duchamp’s family can be determined by the way that they volunteered for war duties. Later, in 1919 Duchamp’s American friend, Katherine Drier, recognised the fixed views of his father, Émile Duchamp, during the Versailles negotiations.17 He had been captured in 1870 and imprisoned in Stettin until the final capitulation.18 It is clear to see how his political sensibilities would have hardened against a military defaulter, and how patriotic duty and anti-German sentiments were a natural part of the family ethos. Duchamp’s exemption from the army in 1909 was nevertheless mysterious and as puzzling then as it is to today. His military papers contain neither the evidence about his medical condition, nor the terms of his medical exemption. A ‘heart murmur’ or ‘insufficences cardiaque’ is occasionally referred to in the Duchamp literature. Nevertheless, Duchamp’s ready appropriation of the ‘heart’ as a metaphor for larger interconnecting systems suggests that the distress caused by this ‘heart murmur’ was perhaps not physiological.19 The problem lay elsewhere: ‘ given that … ; if I suppose that I am suffering a lot’,20 he reminds himself in one of the notes in his ‘Box of 1914’ and armed, accordingly, with this unexplained ‘supposition’ he set himself against his family’s desires and expectations.

Nevertheless, Duchamp demonstrated in his ‘Jura-Paris Road’, that even if his attitude to public policy was out of sympathy with the national mood, military concerns preoccupied him. Following the 1870 defeat, successive Republican governments had aimed to deflect volatile nationalist attention away from its territorial losses in the east of France by engaging in a vigorous policy of colonial expansionism. The outlandish objects that appeared in Paris museums as trophies of French colonialism were testament to this progress and the seminal position of African figuration within the cubist achievement is now thoroughly understood. Duchamp, in his search to find ways beyond the prohibitive restrictions of cubism, looked towards the procedural effects rather than the material affects of French colonialism. Unlike the cubists who drew formal solutions from plundered artefacts, Duchamp considered foreign interventionism at the level of territorial expansion and military occupation, and these can be seen in the preoccupations that concern him in the ‘Jura-Paris Road’. Increasingly, however, Germany was beginning to contest French pre-eminence overseas, most notably in North Africa, where, at the Algerian port of Agadir in 1911, the two forces came dangerously close to conflict. French colonialism, triggered surely by this developing crisis, appeared among Duchamp’s preoccupations slightly more than one year later in October 1912 when he outlined the problem in the constellation of notes that he wrote after the journey. In one of these he elides themes of colonialism along with its other problematic themes of territorial expansion: ‘the chief of the 5 nudes manages little by little the annexation / of the Jura-Paris road. The chief of the 5 nudes annexes to his estates, a battle / (idea of colony).’21

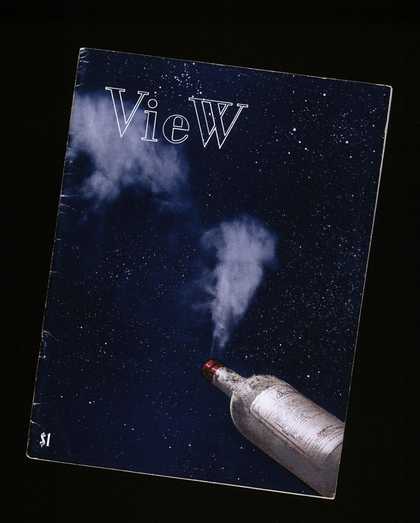

Fig.15

Marcel Duchamp

Cover for ‘View’ Magazine 1945

Tate Library © Succession Marcel Duchamp 2006, ADAGP/ Paris, DACS, London

Military preoccupations

As the evidence of the 1912 ‘Jura-Paris Road’ makes clear, Duchamp’s conscription was by no means the end of his fixation with military culture and this can be seen in a range of works that he produced throughout his life. Several of his published cartoons depict soldiers, and one of them titled Éxpérience, 1909, comments unfavourably on an army regulation affecting the bridal arrangements of officers. The intractable nature of the situation is a premonition of the disappointing transactions between the Bride and her unlucky Bachelors in the Large Glass . Although the dates for the Large Glass are listed as 1915–23, these do not properly account for the preparatory notes and preliminary sketches from 1912 and so the Glass actually sits astride the war years of 1914–18, developing its thematic urgency in the build-up of military tension while gradually losing momentum in its aftermath. The demise of the Glass and its reconstruction provides a further parallel with the military situation in Europe. Military themes appeared again with his design for the title page of View a magazine that devoted its March 1945 issue to Duchamp (fig.15). On the cover he arranged a photomontage of a wine bottle displaying the redundant Certificat de bonne conduit, his military service record of forty years earlier. The evidence from these military papers resurrects his struggle with the conscription boards and show that military interest in Duchamp lasted until 1930.22

Duchamp’s decision to use his army papers emphasises how the military and the personal aspect of the work were elided. The military aspect is emphasised by the horizontal alignment of the wine bottle with a vertical discharge of smoke escaping as if from the muzzle of a cannon. The bottle menaces a backdrop made up of points of light on a blue ground and so the composition invokes familiar themes of technological determination and dimensional uncertainty, previously seen in the toy cannon and Milky Way of his wartime masterwork The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (fig.4).

Fig.16

Marcel Duchamp

Exhibition Poster for Editions de et Sur Marcel Duchamp 1967

© Succession Marcel Duchamp 2006, ADAGP/ Paris, DACS, London

Finally and at the end of his life, Duchamp produced a poster for the Galerie Givaudan (fig.16). The print shows his outstretched palm, pressing against the picture plane with a cigar provocatively inserted between his fingers. An ejaculatory plume of smoke, emanating from this cigar, mushrooms upwards in a voluptuous parody of an atomic cloud (fig.17).23 The image resembles the television footage of France’s third nuclear test, conducted in French North Africa on 27 December 1960.24 Here the contaminated debris drifts upwards with the same insouciant grace as the smoke in Duchamp’s poster. The image in Duchamp is disarmingly sexual but if the salacious intention is forgotten for a moment it will be noted that Duchamp’s creative career, from his juvenile drawings to this final poster, was bracketed at either end by images that reflected on military technology, equipment and power, not to mention, the additional liberties with good taste that his mischievous imagination was capable of developing in relation to the sobering realities of military culture.

Fig.17

French Atomic Explosion 1960

Television footage 27 December 1960

Archived at news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday

Military misalignments

To examine the origins of this flair for subversive humour, Duchamp’s cigar must point back sixty years to the infantry barracks where, as an under-age teenager from a privileged background, he became an army conscript. Within the ranks he would encounter the specialised ability of soldiers to develop facetious slang out of official language. Falling just short of actual insubordination, this expression remains the only critical response soldiers can voice without fear of reprisal.25 Although not immediately evident in his work, the development within Duchamp’s later oeuvres of facetious and punning language can be profitably examined from the perspective of this period of conscription. His exposure to the inspired vulgarity of soldiers in 1905–6, might then be traced to a range of his later works that probed into language to find its destabilising and often prurient second meaning. The military references that followed in Duchamp’s career derive from the misappropriation of official language evidenced in military slang. In the course of his practice he would systematically misinterpret themes of military culture with a persistence that is peculiar among the artists of his generation.

Fig.19

Raoul Trémolières

Mitrailleuse de la Manufacture de Saint Étienne (St Étienne Machine Gun) 1915

Courtesy Louis Trémolières

Reproduced at donjondecoucy/tremolieres/Carnets/carnet5/page24.htm

A different example is to be found in Duchamp’s contribution to a project for the decoration of his brother’s kitchen in Puteaux. He chose to paint a coffee grinder, known in French as un moulin à café (fig.3). The painting that he made dismantles the mechanism, displaying it as an exploded diagram; this was a prosaic and severely functional choice for an ornamental kitchen object, but a very different association might explain Duchamp’s selection of it, revealed in the fact that les moulins à café had become the term for the cumbersome, heavy machine-guns that were issued but largely unused by the French infantry (fig.18). An immediate contextual resonance was provided by the fact that these denigrated and ineffective weapons were made in the local arsenal at Puteaux. Thus the title of Duchamp’s sombre little painting reverberates with the low esteem accorded to the infantry machine-guns while disparaging, by association, the place where his brothers lead their creative lives.26 Infantrymen also carried real coffee grinders in their regulation batterie de cuisine, and so, aside from the purely domestic association of le moulin à café, the meaning of Duchamp’s painting incorporates the social tensions of the Puteaux kitchen, the cooking accoutrements that formed part of the infantryman’s burden and finally the frustrations associated with the discredited infantry weapon.

From 1911 onwards, Duchamp moved beyond domestic references towards situations that indicate newer themes of automation, measurement, mapping, and the incremental division of territory that lay beyond the dimensional remit and comfortable enclosures of Puteaux. These works also develop ideas about the occupation of space that turn into a sustained preoccupation with territory and territorial advantage. One overt cause of this was the military escalation along the eastern diagonal of France that was expressed in a series of strongholds that went from the Belgian border in the north, along the limits of the contested provinces of Lorraine and Alsace to the Swiss border in the east. This disquiet is accurately revealed in the 1912 ‘Jura-Paris Road’, Duchamp’s road journey, starting at Étival in the east of France and ending at Neuilly, west of Paris, followed a parallel just below this militarised diagonal and so the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ became the most inclusive, if obliquely stated of Duchamp’s documents that define his preoccupation with this critical, slanting ‘military space’.

The notes

The ‘Jura-Paris Road’ developed in tandem with Duchamp’s more visible works such as the studies and notes for the Chocolate Grinder and the Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries. This cursory and secretive mode of address gives an indication of his disengagement from the laborious formalism of the studio-centred, object-based art of his brothers. Instead, his practice became subordinated to his changing situation whereby the ideas were recorded and accumulated gradually, as they occurred to him on whatever scraps of paper were available. The notes that he wrote to himself with their occasional reference to location are evidence of the fact that for Duchamp the site of work was beginning to change from his fixed studio to an undefined network of incidental cafés and kitchen tables. His four notes provide a deliberation on the theme of mobility as if written metaphorically to exemplify his own restless, wandering position. However, the imperative, driving the narrative in the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ is an aggressive one concerning the occupation of space, which is achieved through practice and coordination in unfamiliar dimensions. The rigour of this method contrasts strangely with the haphazard approach that he developed in writing and storing his notes. Nevertheless, the notes provide the most coherent metaphor for his resistance to the controlling authorities who were there to limit him from compromising the tenets of cubism in the first instance, and beyond these constraining influences were the military protocols that aimed to keep him in the army for longer than he wanted.

Éloignement

In the shadow of war, Marcel Duchamp assembled a number of key ideas, which he reproduced five times into boxes and distributed among friends. The project is now called the ‘Box of 1914’ and one of the notes in it stands out from the others because of its relevance to the international crisis. It is called Éloignement and it defined Duchamp’s preoccupations with the military and political agendas of the time.27 It begins with Duchamp’s announcement of his opposition to compulsory military service and it was probably provoked by the re-instatement of the three-year law extending the period of compulsory military service. This was one of President Poincaré’s early political initiatives and in making this statement Duchamp revealed his opposition to the troisaniste agenda, which viewed with alarm France’s inability to meet on equal terms the much larger German army, now stationed on France’s side of the Rhine in Alsace and Lorraine. The three-year law aimed to bolster the French army with more troops by providing reserve regiments that could be rapidly deployed once the war had begun. Even so, this law did not produce the required numbers and the problem of matching the much larger German force was partially achieved by interspersing the colonial divisions from North Africa among the metropolitan soldiers along the line of France’s Eastern approaches.

Éloignement begins outspokenly with the statement: ‘Against compulsory military service’,28 followed by a range of oblique observations in a list of contentious military subjects. References in this list include the inappropriate uniform in light of fragmentation sustained from injuries in modern warfare and the consequences of this warfare are then described in terms of human dismemberment. Duchamp caustically suggests that dismembered organs might be revitalised ‘téléphoniquement’, via a technology that, so far, the army did not possess.29 Telephonically, the scattered human remains might be reconnected and used again – if only for a limited period. This note, reveals Duchamp’s pessimistic concerns about the lack of provision for an interconnected conception of military space, he demonstrates an interest in remote communication, or ‘communication at a distance’,30 and so the ‘Box of 1914’ and within it, Éloignement, offers a checklist of Duchamp’s preoccupations at the start of the war and before his departure for America in June 1915. The inclusion of Éloignement within this collection testifies to the personal interest he attached to the issue of conscription in advance of his own provisional release from service. More generally, it describes a lack of fit between the army command and its aspirations to sustain a war across battlefronts where new forms of communication would be needed (fig.19).

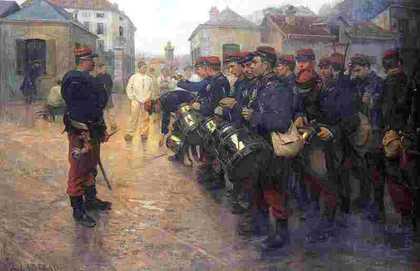

Fig.19

Planche 2. Infanterie de ligne (Plate 2: Infantry of the Line)

Illustration from Jean Augé, L'Armée française d'Août 1914, Paris 1935

Photography: K. Lyons

The ‘Jura-Paris Road’

The four notes that make up the ‘Jura-Paris Road’, although more ambiguously stated are in fact an anxious expression of similar preoccupations. They contain allusions to dimensional space and to ‘communication at a distance’ similar to those found in Éloignement . However, more prosaic information about the route, the weather, the duration of the journey, and Duchamp’s travelling companions, are all missing from the notes. The impression given in the existing literature is that, as a catalyst for Duchamp’s ideas on language and art, the journey generated a positive atmosphere of bonhomie and this motor excursion permitted an exhilarating insight into the links between eroticism, electro-mechanical engineering and dimensional speculation.31 This research suggests that, rather than the convivial outing that history and past scholarship describes, tensions existed, both social and political, that were evoked by the density of military installations along the road they were travelling on and that these induced, in Duchamp, a sense of pessimistic foreboding that was only partially resolved in his flight to America. The military installations that they passed en route provided the backdrop for their conflicting attitudes to patriotism, nationalism and ultimately conscription. The journey was broken at Avallon32 and this fixes it at its mid-point, which then restricts the more elastic possibilities of the itinerary to the garrison towns along Route Nationale Six. Their journey would have taken them through: Lons-le-Saunier, Chalons-sur-Saone, Autun, Auxerre, Joigny, Sens, Fontainebleau, Melun, Vincennes and finally the regimental showcase of Paris itself (fig.1).33 These were towns with predominantly infantry barracks, but the route included the regimental headquarters of other regiments: Chasseurs, Dragons, Zouaves, Genies, Train . Once they had got to Vincennes, the increasing prevalence of artillerie with their new canons de 75 would have been evident.

Duchamp’s description of an aggressive occupation of linear terrain by a co-ordinated detachment of individuals, suggests that they were participants in an extended manoeuvre that can be interpreted as a military operation between points along this road. The objective, according to the title authorises an advance from the Swiss border towards Paris. Military exercises such as this had recently taken place across a broad sweep of north-east France as part of the annual military Manoeuvres d’Automne . Large sections of the army were involved in these combined operations that were intended to test equipment and tactics and to give the previous year’s recruits an idea of combat experience. Troops would still have been on the roads, doggedly marching back to their regional barracks.

The military road

Where the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ leaves behind any resemblance to the operations of the French army of October 1912 lay in Duchamp’s emphasis on a process that synthesised human potential and mechanical systems into one networking whole. Duchamp’s strategies would succeed by absorbing the terrain, the road, the vehicle and the human affiliates into one timeless, flowing, combinatory system. In contrast to this, the French army in 1912, recognised as a supremely effective marching army with remarkable powers of endurance, could be expected to complete the same operation along the road between Étival (Jura) and Neuilly (Paris) in approximately twenty-one days.34 Being ignorant of Duchamp’s notional conception of a mobile and evolving force, the army relied instead on the endurance of its boots and the feet inside them to overcome the terrain. Although Duchamp proposed a timeless synthesis of men and machines in a balance of vital organs and reciprocating parts, in actuality this brought his travellers to their Paris destination in one sustained, if rain-soaked and probably disorientated, twelve-hour period.35

Fanciful as this may seem, Duchamp was making a point about the army’s resistance to strategies that proposed an alternative to the élan of the infantry assault at the heart of French military thinking. It had developed a theory of war that diminished the importance of defensive equipment so that, for instance, the under-regarded machine guns, considered as defensive weapons, were left undeveloped. However, unstoppable momentum depended on both the head and the heart of the army operating as one and this is where Duchamp’s point is made. The army lacked a communications system that could function across the fluctuating terrain of total warfare. Duchamp’s phenomenal descriptions in the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ and in Éloignement both described communication systems where the dispersed units (methodically dispersed in the case of the ‘5 nudes’ of the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ and catastrophically dispersed in the case of the limbs and hearts of Éloignement ) operate in a communicating synthesis. The ‘Jura-Paris Road’ advances towards its objective through an agency called the ‘machine of 5 hearts’. Whereas this is done in a sequence of complex spatial manoeuvres, switching between amplitude and the simple reduction of a straight line, there is no such progress in Éloignement. In contrast Duchamp imagines there the exhausted aftermath of an operation and the cynical manipulation of terminally injured soldiers. Whereas the 1912 ‘Jura-Paris Road’ projected a metaphysical speculation, first invoked in the technological and visionary language of de l’Isle-Adam and Alfred Jarry, the bleak positivism of Éloignement, by comparison, is conveyed in the language of perverse army guignol and anticipates the gallows humour of 1914.36

L’Enfant phare

Duchamp’s ‘Jura-Paris Road’ also focused on institutional aspects of military behaviour, and specifically on the army’s connection with the Catholic Church. This connection provided the moral justification for foreign adventurism as well as a binding identity that linked it to a nationalist/monarchist constituency at home. Prior to 1912, Catholic military identity focused on the Society of the Sacred Heart and found its actual form in the basilica of the Sacré Coeur, approaching completion above Montmartre.37 This was situated towards the end of Duchamp’s 1912 journey. The mysterious ‘machine with 5 hearts’ of these notes, was epitomised also in the living organism of the basilica, already a place of vigil and prayer, where the artist Luc Olivier Merson installed a ceiling mosaic illustrating, beneath the images of the Trinity and the saints of France, a frieze that included two French generals who, in 1870, went into action at the Battle of Loigny with the Sacred Heart emblazoned on their Regimental Colours (fig.20). On the opposite side this frieze shows the gratitude of the colonised races, euphemistically referred to in the guidebooks as the ‘homage of the continents’. Associated themes also register within the sweep of Duchamp’s ‘Jura-Paris Road’.

Fig.20

Luc Olivier Merson

Ceiling Mosaic 1912

Basilique du Sacré Coeur, Paris

Reproduced at www.panoramas.dk/fullscreen/fullscreen24.html

Photography: Laurent Thion

In what appears to be an early version of the same note, Duchamp began to develop his conception of its chief protagonist, the ‘headlight-child’, and although not yet fully developed, he described him simply as: ‘this headlight being the child-God, rather like the Jesus of the primitives’38 This unexpected citation of the central figure in Christian mythology, references again the Church and its role in giving a moral justification that eased the conscience of French colonial expansion. This close relationship between the Catholic Church and the officer cadres, who in their turn disguised and then masked and then denied their racism, resulting in the anti-Semitic persecution of Dreyfus, divided France politically and provoked the decline of the army between 1894 and 1912.39 This period of divisive military unpopularity coincided with Duchamp’s formative years, when although photographed as a young military cadet in 1895, his own developing éloignement from the aspirations and obligation towards the military ambitions of his country were beginning to emerge.

![Planche 7: Chasseurs à pied (la fanfare) (Plate 7: Light Infantry) [composition of the regimental fanfare] Illustration from Jean Augé, L'Armée française d'Août 1914, Paris 1935](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/light_infantry_0.width-420.jpg)

Fig.21

Planche 7: Chasseurs à pied (la fanfare) (Plate 7: Light Infantry) [composition of the regimental fanfare]

Illustration from Jean Augé, L'Armée française d'Août 1914, Paris 1935

Photography: K. Lyons

Drawing on his language experiences as a conscript, Duchamp developed his conceptions of the enfant-phare, an illuminated child, which in the original French is also phonically caught in a military-mystical aura. The rhythms and regular repetitions of the phrase ‘enfant-phare’ in the ‘Jura-Paris Road’ echoes the military term le fanfare that alludes to the position and the function of the infantry band (fig.21).40 Marching infantry columns were headed by formations of buglers or fanfaristes who, when attached to regimental drummers, formed a unit known as la clique going ahead of the main marching columns, their music fanning out ahead of them like the tail of a reversing comet:

This headlight child could graphically, / be a comet, which would have its / tail in front, this tail being an / appendage of the headlight child.41

The phonic slippage between ‘enfant-phare’ and the French ‘fanfare’ does not easily work in an English translation but nevertheless, suggests a reference to the mystical aura that arises from the combinatory form of the two nouns ‘enfant’ and ‘phare’. ‘Enfant-phare’ has been mechanistically translated into English as the ‘headlight-child’, taking its lead from the automotive experience of the journey from where the term arose. This technical reading seems to deny a more illusive implication that invests the term with an ethereal glow that goes closer to the idea of ‘phare’ in its original meaning of a glowing object or beacon – perhaps transmitted from a lighthouse as André Breton suggests in the title of his seminal essay in 1934 on Duchamp’s Large Glass and then published in View in 1945 before the English translation had established the term as a ‘headlight’.42

The material road

The Jura to Paris excursion did not necessarily begin as a theoretical speculation into military culture and terminology. It began, prosaically enough, when Marcel Duchamp in the company of the poet Guillaume Apollinaire travelled with Francis Picabia in his car to the Jura. Their reasons for travelling may simply have been sociable. If so, they had time to regret their decision on the long journey. The seasonally short days meant that much of the journey passed by in darkness and by the time they reached their destination in the early hours of the morning they had travelled slightly more than four hundred and eighty kilometres and rain followed them throughout. Gabrielle Buffet, who was waiting for them, recalled her husband’s arrival with his two friends in the small hours of the morning, in conditions that she described in terms of ‘une pluie diluvienne’ (torrential rain).43

This research into the motoring conditions of the period allows no more than an informed guess at the conditions on the stages of the journey as they travelled past the military installations en route. They would be tired and the supply of fuel and acetylene for the headlights would be depleted. They would have had difficulty in seeing through the driving rain and the muddy spray thrown up by the wheels of the car. In a detail of Duchamp’s note that says more about the motoring rather than the military aspects of the journey, he uses the term ‘powdered silex’. Silex is of course flint and contemporary travel guides produced by manufacturers such as Michelin and Continental advertised various solutions that were designed to withstand laceration from silex road surfaces. In wet conditions when the Jura mountain roads turned into torrents of water, the flinty substrate had a tendency of working through to the surface, which brought the sharp stones into troublesome contact with the tyres of the car. When driving after dark – an activity that the guide books cautioned drivers against44 – road-side repairs, necessitated by the effects of silex on tyres, would have to be carried out under the emergency lighting from the vehicle’s own acetylene head-lights.45

Over the course of a night ride, two years later, in August 1914, on the eve of enlisting into the army, Apollinaire described an episode where three punctures unexpectedly prolonged the duration of the 200-kilometre journey back to Paris. This was on a hot summer’s night, which unavoidably lengthened into the early hours of the following morning. On this occasion, the acetylene supply for the headlights ran out as they were doing their repairs and the journey eventually finished off in sunshine just as the general mobilisation notices were being posted up. Apollinaire remembered the night journey with satisfaction and the roadside repairs provided a sense of purpose, which he described in awed terms as if it had been a preliminary rite of passage to the ultimate military test of going to war.

We realised my comrade and I

That the little car had driven us to a new epoch

And although we were full-grown men already

We’d just been born.46

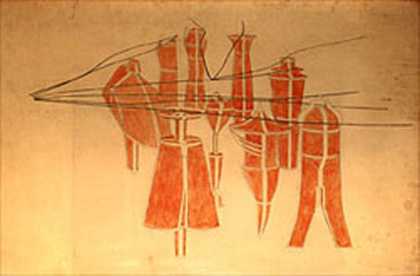

Fig.22

Marcel Duchamp

Cemetery of Uniforms and Livries No.2 1914

Yale University Art Gallery © Succession Marcel Duchamp 2006, ADAGP/ Paris, DACS, London

During the course of Duchamp’s journey from the Jura to Paris in October 1912, the car tyres will have suffered comparably except the journey was more than twice the length and the roads in the mountains more unpredictable and so the punctures would have multiplied into the wet night. Duchamp’s ‘Jura-Paris Road’ allows none of the awed satisfaction of Apollinaire’s summer journey. Duchamp’s description is preoccupied with encountering change through discipline and training and behind these requirements we can detect his presentiments about military preparations, colonialism and the problematic religious underpinning of the French army. Whereas Apollinaire approached the conflict in his writing with patriotic enthusiasm, Duchamp exhibits something close to morbid fatalism in the face of the overwhelming military escalation that would abruptly turn peace into war in 1914 (fig.22). In this series of tensely coded notes that have come down to us as the ‘Jura-Paris Road’, Marcel Duchamp momentarily illuminated his concerns and premonitions of the gathering military situation in France (fig.23).

Fig.23

Albert Larteau

Tambours et clairons (Drums and Bugles) 1905

Nancy, Musée des Beaux-Arts

Appendix 1

Marcel Duchamp, Green Box, 1934 from M. Sanouillet and E. Peterson eds., Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (Marchand du sel), New York 1973, reprinted as The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, New York 1989, pp.26-7.

The machine with 5 hearts, the pure / child of nickel and platinum must / dominate the Jura-Paris road. On the one hand, the chief of the 5 nudes will be / ahead of the 4 other nudes towards this Jura-Paris road. On the other hand, the headlight / child will be the instrument conquering this Jura-Paris road

This headlight child could graphically, / be a comet, which would have its / tail in front, this tail being an / appendage of the headlight child / appendage which absorbs by / crushing (gold dust, graphically) / this Jura-Paris road.

The Jura-Paris road, having / to be infinite only humanly, / will lose none of its character of infinity / in finding a termination at one end / in the chief of the 5 nudes, at the other / in the headlight child. The term “indefinite, seems to me (more) accurate / than infinite. The road will begin / in the chief of the 5 nudes. and will not / end in the headlight child.

Graphically, this road /will tend towards the pure geometrical line / without thickness (the meeting of 2 planes / seems to me the only pictorial means to achieve / purity) But in the beginning (in / the chief of the 5 nudes) it will be very finite in / width, thickness (etc), in order little by little, / to become without topographical form in coming close to this ideal straight line which / finds its opening towards the infinite in the headlight / child.

The pictorial matter of this Jura-Paris road / will be wood which seems to me like /the affective translation of powdered silex. Perhaps see if it is necessary to / choose an essence of wood. (the fir tree, / or then polished mahogany)

Appendix 2

Paul Matisse ed., Marcel Duchamp, Notes, trans. Matisse, Boston 1983, unpaginated.

- Pictorial Translation – / The 5 nudes, one the chief, will have to lose, / in the picture, the character of multiplicity. / They must be a machine of 5 / hearts, an immobile machine of 5 hearts / The chief, in this machine, could / be indicated in the centre and at the top, without appearing to be anything other than a / more important gear train (graphically).

The machine of 5 hearts will have to / give birth to the headlight. / This headlight will be the child-God, rather / like the primitives’ Jesus. / He will be the divine blossoming of / this machine mother.

In graphic form, I see / him as pure machine compared to the / more human machine-mother. He will have to be radiant with glory. And the graphic means / to obtain this machine child, / will find their expression in the use / of an endless screw. / (accessories of this endless screw, serving to unite / this headlight child God, to his machine-mother. 5 nudes- The chief of the 5 nudes manages little by little the annexation / of the Jura-Paris road.

The chief of the 5 nudes annexes to his estates, / a battle / (idea of colony)- Title. / The chief of 5 nudes extends little by little his / power over the Jura-Paris road.

There is little ambivalence: after having conquered / the 5 nudes, this chief seems to enlarge / his possessions, which gives a false / meaning to the title. (He and the 5 nudes form a tribe / for the conquest by speed of / this Jura-Paris road)

The chief of the 5 nudes increases little by little / his power over the Jura-Paris road.

The Jura-Paris road, on one side, the 5 nudes one / the chief, on another side, are the two / terms of the collision. This collision / is the raison d’être of the picture. To paint / 5 nudes statically seems to me without / interest, no more for that matter than to paint / the Jura-Paris road even by raising / the pictorial interpretation of this entity / to a state entirely devoid of impressionism. / Thus the interest in the picture / results from the collision of these 2 / extremes, the 5 nudes one the chief and the / Jura-Paris road. The result of this battle / will be the victory obtained little by little by the 5 nudes / over the Jura-Paris road.

Appendix 3

Marcel Duchamp, ‘Box of 1914’: Éloignement (Dispersal), trans. Kieran Lyons, 2005.

‘Against compulsory military service: a “dispersal” of limbs, of hearts and other anatomical parts; each soldier is unable to get back into uniform, the heart will provide a telephonic supply to dispersed limbs etc.

Then no further supply; each “dispersed” limb is isolated. Finally a regulation of regrets from one “detachment” to another.’