Tate’s collection includes a number of important paintings by John Constable (1776–1837). Many of these works, which span the artist’s oeuvre, have been cared for at Tate (some previously at the National Gallery, London) for more than ninety-five years. One frequently displayed painting is Sketch for Hadleigh Castle, c.1828–9,1 a full-scale oil on canvas, painted in preparation for the finished ‘six footer’ landscape that was exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1829. One of ten full-size sketches which Constable took the trouble to execute,2 it was perhaps designed to test the effect of a dramatic sky on a large scale.3

Existing conservation documentation, detailing technical findings and treatments, was found to be sparse. The records did, however, note the presence of ‘strips added at left and bottom’, a feature that has been mentioned in the art historical literature on the painting. Interestingly, there has been disagreement over who was behind the additions among leading scholars on Constable’s work. In the late 1970s, with the benefit of X-ray examination, Tate curator and leading Constable specialist Leslie Parris in the late 1970s was of the opinion that the additions of canvas were made and painted on by ‘someone other than Constable’.4 Graham Reynolds disputed this in 1984, saying, ‘I do not agree that the scientific evidence warrants this conclusion’, and adding, ‘if the theory of another hand were to be accepted it would imply that Constable had cut his composition through the middle of the body of the dog following the shepherd and not expressed the left-hand side of the further tower’.5

Technical examination was carried out by the author, focusing in particular on the hand and date of the additions. The painting’s current lining, which incorporates the additions, predates 1936 (the year of the earliest known photography of the work) but there is no known record of the date of the alterations. The painting’s horizontal dimension is 1684 mm (65 7/8 inches), similar to the Stoke by Nayland full-size sketch, somewhat less than six foot (72 inches). The additions to the Hadleigh sketch measure 90–100 mm wide at the left edge and 100–125 mm wide at the bottom. They are made from plain woven linen, rather than the twill weave used for the main canvas, and are lined in with glue paste not sewn. Constable’s use of twill fabric for the main canvas is of interest since he rarely employed this canvas type. It has only otherwise been found as a support for the small, early sketches: Valley Scene, Dedham Vale and A Lane near Dedham, all dated 1802.[fm]Sarah Cove, ‘Constable’s Oil Painting Materials and Techniques’, in Leslie Parris and Ian Fleming-Williams eds., Constable, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1991, p.494. Its use may indicate that Constable resorted to an available length of canvas from his studio, in the absence of his preferred supply, perhaps in a hurry to get started on the sketch.6

Alterations to paintings years after completion are not uncommon but, to complicate the issue, it was also ‘constant practice for Constable to enlarge the canvases on which he was working’, as Reynolds points out, citing Wivenhoe Park, Essex 1817 (NGA Washington) and Weymouth Bay ?1819 (Louvre) as examples. He continues: ‘These additions were either on the same canvas differently grounded or on a different canvas’.7 In each case, the reason for Constable’s modifications seem related to his desire to improve the space and/or viewing perspective of his composition. Other instances of Constable’s additions to his ‘six footers’ are: Sketch for the Lock ?1823 (Philadelphia) and The Leaping Horse 1825 (Royal Academy of Arts, London).

Unframed and well lit in the conservation studio, the additions stand out from the rest of the composition owing partly, to a marked yellow tonality to the paint, particularly in the sky of the left addition (fig.2).

Fig.2

Detail from Sketch for Hadleigh Castle, upper left, showing yellow hue to paint at extreme left edge

Tate Conservation

© Tate 2005

Analysis of paint dispersions found that six out of seven samples from the additions contained a significant amount of yellow in the pigment mixture. Samples from the main canvas showed no such prevalence. Furthermore the painting bears a distinct network of age cracks which one would expect to extend on to the additions if contemporary with the main canvas, but this is not the case (fig.3). Diagonal cracks at upper left indicate the original corner was within the twill canvas rather than skewed to the left where the addition now is.

Fig.3

Detail from Sketch for Hadleigh Castle, upper left, showing variations in paint application and crack pattern between addition at left and main canvas at right

Tate Conservation

© Tate 2005

On the gallery wall, the conspicuousness of the additions is somewhat reduced by the shadow of the frame. The added strips, however, remain clearly visible to the keen observer. This is not to say that the individual who altered the painting’s dimensions did not go to considerable effort to distract the viewer’s eye. The close match of texture, pigments and painting style with the main canvas is successful enough to have convinced connoisseurs that paint on all pieces of the canvas was worked by the same hand. Those who disagreed, however, called the additions ‘crudely painted’,8 and ‘incompetently handled; the left side of the left hand tower is especially feeble, being misrepresented as a flat instead of a curved surface’.9

A cross section illustrates how the left addition consists of primed canvas which had previously been painted, varnished, and allowed to accumulate dirt before being reused. On the lower addition (made up of two sections of canvas), the X-ray reveals part of an underlying composition including a classically painted hand holding a pen or instrument (fig.7). Constable has been known to add eccentric extensions to his supports10 but none involve a cut-up painting.11

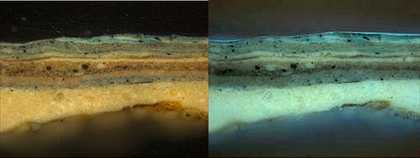

During the second campaign of painting on the additions, three layers of paint were applied (each approximately 50-80µm thick) on top of a fresh ground (fig.5). By contrast, an equivalent cross section from the sky of the main canvas reveals eight, typically 10–30µm thick, paint layers (fig.4).

Fig.4

Cross section from Sketch for Hadleigh Castle: sky of main canvas, in normal light at left, UV light at right

Tate Conservation

© Tate 2005

Fig.5

Cross section from Sketch for Hadleigh Castle: sky of left addition, in normal light at left, UV light at right

Tate Conservation

© Tate 2005

As well as this difference in build up, the paint and ground of the left addition have a distinctive blue fluorescence in UV (figs.4–5). It has been suggested that the cause may be wax, added to body the paint to imitate Constable’s multilayered technique on the main canvas.12 Descriptions of Constable’s painting technique often cite his use of a palette knife to achieve textured surfaces, and the sky in the Sketch for Hadleigh Castle is a case in point.13 The author’s recent technical examination found no such tool marks on the main canvas. There is evidence in the sky of the left addition, however, in the form of broad flat strokes and ridges of accumulated paint (fig.3), a further discrepancy in paint application between the main canvas and the additions. Another finding from analysis of the additions include: the tentative identification of synthetic ultramarine. Constable thought this inferior to the natural pigment,14 and it was little used following its invention15 in 1826–8.16 It was therefore unlikely to have been used by Constable for this work or even during his lifetime. Analysis also showed the presence of barium chromate, rarely found in Constable’s paint, and of small particle size suggesting modernity.17 Furthermore, the second ground bears no cracks, a slight indicator of its being more recent than 170 years18 or being part, from the beginning, of a lined painting.19

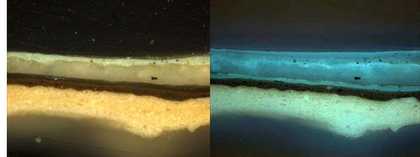

When raking light is passed over the surface of Sketch for Hadleigh Castle, thickly applied brushstrokes, raised cracks and the borders of the additions are all emphasised. Close examination reveals lines of cracking which relate to the bar marks of the original stretcher (fig.6).

Fig.6

Raking light photograph of Sketch for Hadleigh Castle. Red lines help locate original stretcher bar marks

Tate Conservation

© Tate 1997

Those most apparent extend vertically towards the left edge, right edge and centre (there are also cracks to indicate a diagonal brace in the upper right corner). What can be deduced from the cracks is that the left stretcher bar was originally positioned within the main area of the canvas, indicating that the additional left strip was added later. Using a raking light photograph, E.G. Coveny (Tate, 1959) drew a scaled diagram of the support to estimate the original width of Constable’s canvas. Measurements made from cross bar marks to the cut edge of twill canvas are: 767 mm at right and 752 mm at left. Assuming the cross bar is central, we can calculate that a mere 15 mm of Constable’s twill weave canvas is missing on the left side. The original height cannot be estimated in the same way since the stretcher evidently had no horizontal cross bar and consequently no lines of horizontal craquelure were produced. Since the paint layer would need to be aged and brittle enough to develop the bar marks of the original support, it is not possible that Constable added the strips (and replaced the support) within the year, that is, before embarking on the finished version of Hadleigh Castle . For the same reason it is also unlikely he did so during the remaining nine years of his lifetime.

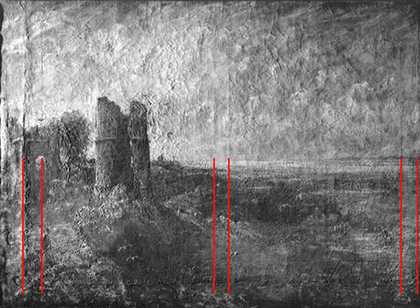

With these findings we should return to Reynolds’s argument that the leftmost ruin and dog would be incomplete without the additions. The X-ray reveals that the main canvas is very damaged at left and bottom edges, with lengths of loss approximately 15–30 mm in width (fig.7).

Fig.7

X-ray mosaic of Sketch for Hadleigh Castle

Tate Conservation

© Tate 2005

The additional strips of canvas were joined to the ragged edges of damaged canvas20 and paint applied on top allowed to encroach onto the main body of canvas to reconstruct the lost composition, including the rear and tail of the dog. Thus, the dog and ruin we now see are partly original, partly reconstructed. Lining up painting and X-radiographs, we can see sufficient space within the damaged area to encompass the whole body of the dog (fig.8) and perhaps a slimmer left side to the ruin, but little more.

Fig.8

Detail from Sketch for Hadleigh Castle, lower left corner. Area of red striations indicates original paint loss as revealed by the X-ray

Tate Conservation

© Tate 2005

Lengths of paint loss along two adjacent edges of a painting, as opposed to all four, are uncommon, creating uncertainty as to the cause. The damage could have resulted from affixing the additions,21 although this seems unlikely judging by the scale of the losses. A more likely cause is prolonged exposure to moisture, retained in the stretcher bars or frame rebate. Hung slanting away from damp walls and allowing air circulation, the upper edges of paintings frequently suffer less than the lower in poor environmental conditions. However, one would have expected comparable damage to the right side of the canvas. A plausible explanation is rolling and storing the canvas with the right edge protected within the roll and left edge exposed. Another is that the right edge has been trimmed of damage prior to lining. Whatever the cause, the losses of paint are cleaved from sharp edged cracks which could only have formed on an aged paint film. Since the damage occurred prior to the attachment of the strips, this suggests the additions are not contemporary with Constable’s painting.

It is possible that the composition of the Hadleigh sketch never exactly matched the exhibited version. Other ‘six footers’ such as The Opening of Waterloo Bridge, Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, The Hay Wain and The White Horse also have compositional differences between sketch and finished painting at their edges. It should be considered that the additions did not replace damaged parts of the original but actually enlarged Constable’s work. Without the additions similarities are apparent with the rapid pencil sketch from life (1814, Victoria and Albert Museum, London) from which Constable’s design for Hadleigh Castle originated. The drawing accommodates little space between leftmost ruin and the edge of the paper support.

Returning to the current appearance of the Hadleigh sketch, the yellow tone of the additions can be explained by a restorer/artist trying to match his paint to Constable’s, masked by a discoloured varnish (since removed). The same paint with yellow hue has also been applied over the small, T-shaped tear at the centre of the painting, a sign of restoration practice. If the additions are not Constable’s, an explanation for another hand enlarging a preparatory ‘sketch’ could be a collector’s desire to have his work accurately matching a known composition. The additions may have been commissioned when the canvas had become brittle enough to have formed stretcher bar marks and sharp edged losses. Certainly, by the early twentieth century the exuberance of Constable’s later sketches had become highly fashionable and valuable enough to warrant the considerable labour and expense of the extensions. In 1921 Charles Holmes talked of his generation ‘becoming perhaps just a little impatient’ of the finished pictures. He said, ‘the time is not I think far distant, when Constable’s greatness will be seen to rest far more upon his brilliant sketches and studies’.22 By the 1940s Kenneth Clark acknowledged a generation who, with eyes ‘dilated by half a century of impressionism’, generally favoured the full-size sketches over exhibition canvases,23 a spectacular reversal of earlier taste, when at the 1838 artist’s studio sale the finished painting sold for £105 and the sketch for a meagre £3.13s.6d.

The Hadleigh sketch remained in the original purchaser’s family for several generations, eventually being sold, presumably damaged, to the long established Leggatt dealers in 1930. It was then bought by Percy Moore Turner, a dealer and celebrated connoisseur of Impressionist and Post Impressionist painting.24 A theory has been formulated by the author that the additions were commissioned by Moore Turner with reference not to the finished version of the painting, by then in a private collection in the United States, but to David Lucas’s mezzotints. In the early 1830s Lucas made two mezzotints from Constable’s exhibited painting. Interestingly, the leftmost ruin in the smaller mezzotint is most in keeping with the flat reconstruction of that depicted on the sketch’s addition. The author’s theory is given credence through Moore Turner’s professional friendship with Andrew Shirley, the cataloguer of mezzotints after Constable (published in 1930) who could have facilitated access to the prints, part of the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Moore Turner sold the painting to the National Gallery in 1935 but the painting is said to have been ‘talked about with interest before this’ date.25 Charles Holmes, then director, mentions it in his introduction to The Letters of John Constable to C.R. Leslie in 1931.26 Somewhat ironically considering the recent examination, he calls it, ‘a brilliant piece of palette knife work … in a period when brushwork in general was sober, smooth or “pretty”, such vigorous scrapings and slashings and loadings of pigment must indeed have seemed chaotic and revolutionary’. Holmes assumed on acquisition that the painting was the exhibited version of Hadleigh Castle. He stated in 1936: ‘We may be proud and thankful that Trafalgar Sq now possesses this convincing proof [of Constable’s] modernity and power’. Extensions to the composition may have been made on the (correct) assumption that Lucas’s mezzotints were made from the finished version. Not long after, discrepancies in provenance between sketch and exhibited versions were found and the conclusion drawn that the latter work was still missing,27 and not to be found for another twenty-four years in 1960.28

On balance, the recent technical examination suggests that strips of canvas were added to Sketch for Hadleigh Castle by someone other than Constable. As discusssed above, the following findings have been used to draw this conclusion: the location of original stretcher bar marks within the main canvas; differences in materials and techniques between main canvas and additions; and the presence of long established damage prior to alteration. The lack of cracking on the additions, the change from private to commercial ownership, and the increased taste for Constable’s sketches all help suggest a date for the alterations of around 1930.