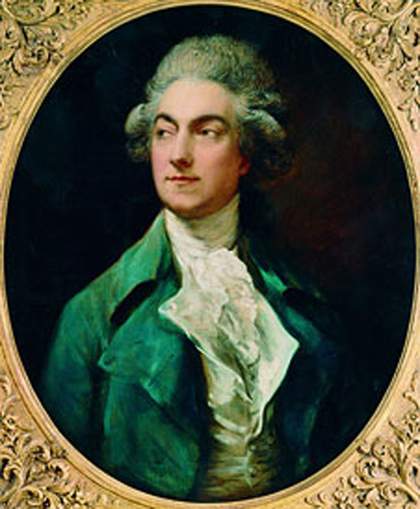

The new displays inaugurated at Tate Britain in the autumn of 2001 saw the introduction of a series of important loans from public institutions and private individuals. It also provided an exciting opportunity to look afresh at works in the permanent collection and consider them in new contexts. One of the principal galleries devoted to the eighteenth century was entitled ‘Britain and Italy’. Here, artistic and cultural cross-currents were explored, not only through the works of British artists in Italy, but through the presence of Italians in Britain: painters, engravers, sculptors, actors, dancers, and musicians. In course of preparing this display it was decided to include a small portrait of the dancer, Marie Jean Augustin (called ‘Auguste’) Vestris, attributed to Thomas Gainsborough’s nephew, Gainsborough Dupont (fig.1). The picture, transferred to the Tate Gallery from the National Gallery in 1955, had only been displayed once before at Tate, in the 1976 exhibition devoted to Gainsborough’s Giovanna Baccelli.1 However, despite its low public profile, it has since proved to be far more visually interesting and historically significant than one might have imagined. Indeed, recent research and conservation have confirmed that the picture, rather than being a portrait by Dupont, is by Gainsborough himself.2 Moreover, it can be dated to about 1781, the year in which Auguste Vestris made his triumphant debut on the London stage. The portrait sheds new light on Gainsborough’s close relations with world of the stage, and on the very nature of his artistic practice. The rehabilitation of this picture also serves as a reminder that ‘lost’ works may not necessarily be missing but simply misattributed.

Thomas Gainsborough, formerly attributed to Gainsborough Dupont

Marie Jean Augustin Vestris (c.1781–2)

Tate

The early history of the painting, before it was exhibited at Royal Academy in 1872 by James Rannie Swinton, is unknown. Swinton presented it to the National Gallery in 1888 as a portrait of ‘Vestris the Dancer’.3 The National Gallery’s Annual Report of that year, recorded the work as a ‘“Portrait of a Young Man”, by Thomas Gainsborough, R.A.’, although unaccountably there was now no mention of Vestris. It continued to be catalogued merely as the portrait of a young man until 1946, when the portrait was discussed at greater length in Martin Davies’s seminal catalogue of the British School. Here, for the first time, the sitter was tentatively identified as ‘Marie-Auguste Vestris’. As Davies pointedly observed, the picture had been presented as a portrait of ‘Vestris the Dancer’, ‘an identification that in the Gallery has never even been discussed’.4 Davies correctly deduced that the sitter in the portrait was probably Auguste, rather than his father, Gaëtan Apolline Balthazar Vestris, whose portrait by Gainsborough had been illustrated in the Burlington Magazine in 1905, and which is illustrated here in colour for the first time (fig.2). Davies also noted the similarities between the two works. He was less convinced by the attribution to Gainsborough, and concluded that it was ‘more probably either a copy of a life-size Gainsborough (missing) or an original by a close imitator’ – a point we shall return to later.5 Seven years later, in 1953, Sir Ellis Waterhouse published a comprehensive checklist of Gainsborough’s portraits in the Walpole Society. Although he included the portrait of Gaëtan Vestris, of the present portrait Waterhouse noted merely that it was ‘formerly wrongly called Vestris’ and ‘probably by Dupont’.6 In his catalogue raisonné of Gainsborough’s oil paintings, published 1958, Waterhouse again included the portrait of Vestris senior, although no mention was made of the present picture. In the meantime, in 1955, the National Gallery gave ownership of the present portrait to the Tate Gallery: one of a series of transfers which followed the Tate and National Gallery Act, which established the Tate Gallery as an independent institution with it own board of Trustees.

Fig.2

Thomas Gainsborough

Gaëtan Apolline Balthazar Vestris 1781

Oil on canvas

Private collection

On entering the Tate’s collection the portrait of Vestris was attributed to Gainsborough Dupont. In the 1960s the waters were muddied further when an American scholar, Charles Merrill Mount, suggested that the picture was a self-portrait by the American artist, Gilbert Stuart, painted with assistance from Dupont.7 This suggestion was firmly rejected by the Tate, on the grounds that while Stuart had grey eyes, the sitter’s were brown. The attribution to Dupont was, however, retained.8 In the 1976 Tate exhibition marking the acquisition of Gainsborough’s portrait of Giovanna Baccelli, the curator Elizabeth Einberg reaffirmed the identification of the sitter as Auguste Vestris, stating that it was ‘of long standing and quite acceptable’.9

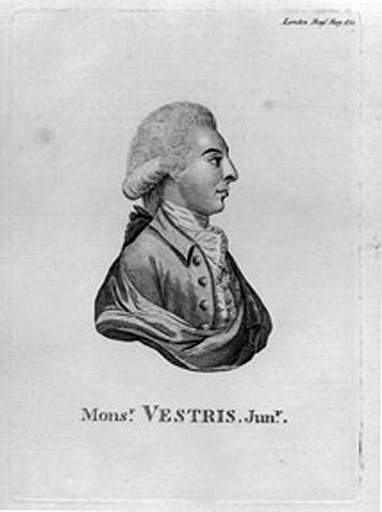

Fig.3

Unknown engraver

‘Mons.r VESTRIS, Jun.r.’

Line engraving

Published in the London Magazine, May 1781

By permission of the Trustees of the National Portrait Gallery

Indeed, it can proved beyond doubt that the portrait is that of Auguste Vestris, by comparing it with other images of the young dancer. These include a head-and-shoulders profile portrait which appeared as an engraving in the London Magazine in May 1781 (fig.3), around the time that Gainsborough painted his portrait. This image exhibits the same distinctive features: the prominent nose, flared nostrils and arched eyebrow. Further confirmation is to be found in a later portrait by the French artist, Adèle Romany (1769–1846). The Romany portrait (fig.4) is undated, but from the costume and the relative ages of sitter and artist, it probably dates from the early to mid 1790s, when Vestris was living and working in Paris.

Fig.4

?Adèle Romany

Auguste Vestris early 1790s

Signed ‘Adele R… ’

Oil on canvas

Whereabouts unknown.

Given the trajectory of Gainsborough’s career, and his close links with the stage, there is every reason to suppose that Gainsborough took a keen interest in Auguste Vestris. Today Gainsborough’s most celebrated depiction of an Italian dancer is his full-length portrait of Giovanna Baccelli (fig.5). Gainsborough exhibited it at the Royal Academy in the spring of 1782. As it has been noted, Baccelli is depicted ‘in character’, in the costume she wore in the popular ballet, Les Amans Surpris, a role she danced with Gaëtan and Auguste Vestris in 1781 at the Italian Opera House (the King’s Theatre) in Haymarket. While Baccelli had already gained a following through her professional life and her notorious liaison with John Frederick Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset, the arrival in London of the Vestrises, father and son, saw her celebrity scale new heights. Gaëtan Vestris had been born in Florence around 1729. Following an itinerant childhood, he arrived in Paris where he established his reputation as a soloist at the Opéra. In 1757 Vestris began an affair with a fifteen-year-old French dancer named Marie Allard. Three years later, on 27 March 1760, she bore him a son, Marie Jean Augustin (called Auguste). In the years to come Gaëtan Vestris became the star of the Paris Opéra, a position which earned him the sobriquet the ‘God of Dance’.10 By the time Vestris senior arrived in England to dance at the King’s Theatre in the 1780–1 season he was the most celebrated dancer in Europe. On 16 December 1780 the younger Vestris also made his debut on the London stage, at the King’s Theatre. Here he performed in a serious ballet, Ricimero, and Les Amans Surpris. The next day Horace Walpole wrote:

The theatre was brimful in expectation of Vestris. At the end of the second act [of Ricimero] he appeared; but with so much grace, agility and strength, that the whole audience fell into convulsions of applause: the men thundered, the ladies forgetting their delicacy and weakness, clapped with such vehemence, that seventeen broke their arms, sixty-nine sprained their wrists, and three cried bravo! bravissimo! so rashly, that they have not been able to utter so much as no since, any more than both Houses of Parliament.11

Thomas Gainsborough

Giovanna Baccelli (exhibited 1782)

Tate

In the weeks and months that followed, the Vestrises took the London stage by storm. On 22 February 1781, on the night of Auguste’s benefit performance, the House of Commons adjourned specially so that the members could be present.12 The doors opened at 6 pm whereupon the theatre was deluged with spectators, who spilled onto the stage. And, after the first act of the performance had been completely lost in the noise and confusion, the ballet ‘gave way to a dance, in which Vestris exhibited himself on purpose to calm the audience’.13 The evening netted Vestris some fourteen hundred pounds. Later that year Bell’s British Theatre published engravings of Auguste Vestris and Giovanna Baccelli in their respective roles in Les Amans Surpris.14 They continued to perform this piece intermittently in London during the 1780s. The Irish playwright John O’Keeffe recalled:

I also saw … in 1781, young Vestris, who owed his celebrity to springing very high, coming down on one toe, and turning round upon it very slowly, while the other leg was stretched horizontally: he was about twenty years of age, and wore light blue, which beame a fashion, and was called Vestris blue.15

Even so, Vestris never quite regained the adulation he had earned during his inaugural season. As the Public Advertiser remarked in 1786, ‘Vestris and Baccelli, tho’ incomparable in some parts of the art, are far inferior as actors to Lepicq and Rossi’.16 Vestris senior returned to Paris in 1781, and did not visit London again until the spring of 1791, nearly three years after Gainsborough’s death. His portrait by Gainsborough must therefore have been painted in 1781. It seems more than likely that that Gainsborough painted the portrait of Vestris junior at this time too.

Gainsborough’s interest in the Vestrises may well have been more than merely professional. Italian artists, composers and performers figured prominently in his immediate social circle, not least during the years following his move to London in 1774. They included the decorative painter, Giovanni Battista Cipriani (‘Dear Cip’), the engraver, Francesco Bartolozzi, and the virtuoso violinist, Felice de’ Giardini. In 1774 both Gainsborough and Cipriani were engaged on producing transparent paintings for the new concert room in Hanover Square, jointly owned by Giovanni Gallini, and Gainsborough’s German friends, Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel. A few years later, in 1778, perhaps at the invitation of Giardini and Gallini (who were both employed there), Gainsborough made for the Opera House two figures representing Music and Dancing, painted in white (possibly trompe l’oeil statues) on the side wings before the curtain, as well as a ‘fine figure’ of Comic Dancing.17 Although these were removed in 1784, and replaced by Corinthian columns, they would have been prominent fixtures in 1781 when the Vestrises first performed there.18 Given the celebrity of the Vestrises, and Gainsborough’s intimacy with the Italian fraternity at Opera House, it is quite likely that he was introduced to them socially as well as in his professional capacity.

The question of Gainsborough’s authorship of the present portrait remains. It was Martin Davies who first raised the possibility that the present picture is a reduced-size copy of a missing prime version, or an original work of art in its own right by an imitator of Gainsborough. It may have been this second suggestion that prompted Waterhouse to introduce the name of Gainsborough Dupont into the equation. The first point to make is that such an attribution has less to do with any resemblance the portrait has to Dupont’s oeuvre than the fact that he has long been a convenient repository for any pictures which do not appear to be characteristic, or fail to meet the high standards, of his master.

Gainsborough Dupont (1754–97) was the second son of Thomas Gainsborough’s sister, Sarah, and Philip Dupont, a carpenter in Sudbury. He was formally apprenticed to Gainsborough in 1772, and entered the Royal Academy Schools in 1775, the year after Gainsborough’s move to London. Gainsborough evidently took him on as much out of family loyalty as any recognition of innate ability or a pressing need for studio assistance. Dupont’s principal duties in studio appear to have been preparing materials and assisting with draperies. Gainsborough did not rate his abilities as a copyist. In 1784, several years after the present portrait of Vestris was made, he deputed Dupont to make a copy of Thomas Hudson’s portrait of Queen Caroline. ‘I have not’, he told his patron, ‘a word to say in favor of the young Man’s Performance; but hope that if your Lordship should not think it well enough for the intended purpose, that your Lordship’s cook maid will hang it up as her own Portrait in the Kitchen and get some sign-post Gentleman to rub out the Crown & Sceptre, and put her on a blue apron, and say it was painted by G— ’.19 Dupont also occasionally made copies of Gainsborough’s portraits, for example, Constantine Phipps, 2nd Baron Mulgrave.20 These, however, are easily distinguishable from Gainsborough’s originals by their coarse handling and the characteristic strengthening of facial features, notably around the eyebrows – also prominent in his independent commissions of the 1790s. The present portrait is by comparison handled with tremendous skill and sensitivity, as recent conservation by Tate conservator Rica Jones has revealed. Indeed, its sheer virtuosity must preclude the possibility that it was made by a copyist, let alone by Dupont.21

Quite aside from the fact that the present portrait of Vestris was until very recently obscured by decades of accumulated grime, and overlayers of varnish, its relatively small size may also have caused scholars to question its status – not least since the majority of head and shoulders portraits by Gainsborough are painted on standard, ‘three-quarter’ length canvases, measuring 30 by 25 inches (76.2 x 63.5 cm). It should be remembered, however, that although Gainsborough generally painted on the scale of life from the early 1750s, he never completely forsook his roots as a ‘miniaturist’ (for example, his small, early oil self-portrait and small portrait drawings) and in the 1760s he painted small pastels of The Duchesss of Marlborough and The Duke of Montagu.22 Around 1769 he painted, although he did not complete, an exquisite small portrait of Elizabeth Singleton (34.9 x 29.8 cm), also in Tate’s collection. Better known are the fifteen small-scale oval portraits (59 x 44 cm) that Gainsborough painted of the Royal family in autumn of 1782, and which he exhibited the following year at the Royal Academy. Even so, it is worth enquring whether Gainsborough did not simply decide to paint the present portrait of Vestris ‘in miniature’, but that he made it as a replica of a larger, and now lost, picture. A solution may lie in the portrait of Vestris’s father, Gaëtan Apolline.

The portrait of Vestris senior was first recorded in the collection of Sir Robert Peel in 1856. It apparently featured among Peel’s collection of politicians and statesmen, before being ‘weeded out’ when the true identity of the sitter was established.23 It subsequently belonged to the celebrated collector-cum-dealer Asher Wertheimer, who purchased it in 1905.24 The portraits of Vestris, father and son, have much in common, both in handling, composition and their theatrical hauteur. The principal difference of course lies in the relative sizes of the portraits. Intriguingly, in his Walpole Society check list Waterhouse noted that, in addition to the present small-scale portrait of Auguste Vestris, there was an identically sized small-scale version of his father’s portrait, which had surfaced briefly in 1919–20. Waterhouse (although he does not appear to have seen the picture) concluded that it, too, was perhaps by Dupont.25 More plausible is that it was the pendant to the present painting. Indeed, its existence opens up the possibility that there was at some time, and may still exist, a larger version of the portrait of Auguste. Could this, moreover, have been the pendant to the larger version of Gaëtan Apolline Vestris, and was it also the painting upon which the present picture in the Tate’s collection is based?

While the notion that Gainsborough willingly replicated his own portraits is anathema to his reputation for painterly virtuosity, the present instance is not a unique phenomenon. He made, for example, two autograph versions of his portrait of Johann Christian Bach: the first for a gallery of famous musicians in Bologna, and a replica, possibly for Bach himself.26 Given the celebrity of the Vestrises and the close social ties that bound Gainsborough to the theatrical world they inhabited, we can speculate that Gainsborough produced two versions of each portrait: one, possibly, for a patron and another for the sitter himself.