Joseph Beuys

Felt Suit (1970)

Tate

For over four decades, artists have used organic or fugitive materials in order to instigate and interrogate processes of stasis, action, permanence, and mortality. Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), along with his contemporary, Dieter Roth (1930–1998), pioneered this practice, probing concepts of energy, warmth, and transformation through the intelligent use of organic materials such as fat. But unlike Roth, who consistently advocated the unconstrained decomposition of his work, Beuys’s position on decay, change, and damage varied from statement to statement, and from piece to piece. As one conservator familiar with the artist’s work noted, in order to understand Beuys’s personal philosophy regarding conservation, ‘it would be necessary to read all his interviews and statements … and even after this, one still might be restricted to speculation as to what he … meant in this special case.’1 Unsurprisingly, museums housing Beuys sculptures and installations generally lack consistent counsel from the artist pertaining to preventive conservation, intervention, and restoration of his work.

Together with codified conservation principles, artists’ statements and documentation (ideally, recorded at the time of acquisition, and at vital points in the work’s lifespan) greatly inform conservation decision-making. But when deprived of a reliable stance from the artist, how can museums address Beuys’s objects and installations that depend upon both material and conceptual activity in order to persist as viable works of art? How do museums define the specific constitution of a Beuys piece, its mutable elements, and its lifespan? The Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, and Tate in London, have confronted, or are currently confronting, these questions. As we shall see, their methods of mediating damaged, decaying, and ageing Beuys works demonstrate how collaborative discussions with conservators, curators, and the artist’s estate engender sensitive decision-making. Significantly, they also illustrate how responsively negotiating each object’s or installation’s idiosyncrasies enable Beuys and his work to resonate continuously within their collections and within culture itself.

One such work lies dormant within Tate’s Archive in London. Tate purchased Joseph Beuys’s Felt Suit 1970 (fig.1), part of a multiple of 100, in 1981. The suit measures 188 x 76 cm and is made of felt, a material Beuys often manipulated to invoke a sense of physical, spiritual, and evolutionary warmth.2 As with all Tate acquisitions, the object was meticulously documented and, notably, flagged as an ‘unusually vulnerable’ item.3 Its vulnerability prompted Tate Conservation to implement written procedures for appropriate handling, display and storage of the work, as Beuys himself did not provide Tate with instructions for its care. In fact, when asked how one should care for Felt Suit, he once announced, ‘I don’t give a damn. You can nail it to the wall. You can also hang it on a hanger, ad libitum! But you can also wear it or throw it into a chest.’4

Interventive treatment of Felt Suit occurred only once, in 1983. Tate Conservation contacted the artist, requesting a matching piece of felt from his studio to repair the suit’s trouser waistband.5

But six years later, severe damage threw Felt Suit’s status as a viable work of art into question.

When Tate curatorial staff requested Felt Suit for display in February 1989, conservators uncovered infestation by common clothes moths ‘in all stages of development’ (fig.2).6

Fig.2

Joseph Beuys

Felt Suit 1970 (photographed after moth damage, 1989)

Felt

Edition 27, no. 45

Tate Archive. Purchased by Tate 1981, de-accessioned 1995 © DACS 2005

Reporting the damage to Tate Director Nicholas Serota, Richard Morphet, the former Head of Collections, informed him that the suit (fig.3),

has been eaten away extensively, with two principal results – the shoulders have largely gone, thus exposing the normally invisible white padding on both sides, and the body of the suit as a whole is copiously penetrated by small holes. The latter are readily visible close-to, though from a middle distance the majority of the surface of the suit gives the appearance of being intact, albeit with a strange change in overall texture.7

Fig.3

Joseph Beuys

Felt Suit 1970 (detail of moth damage)

Felt

Edition 27, no. 45

Tate Archive. Purchased by Tate 1981, de-accessioned 1995 © DACS 2005

Tate’s immediate priority for the work was its conservation. Tate’s then Assistant Keeper, Sean Rainbird, contended that it was crucial to have ‘an accurate conservation assessment’ of the work, even at the expense of its condition entering into the public domain.8 As Beuys had died in 1986, conservators no longer had the option of contacting him for guidance. Tate therefore set about determining viable options for treatment with external textile conservators, and researched examples of other museums’ interventive strategies for Beuys’s felt objects. Upon receiving news of a successful result from fumigation,9 Tate conservators treated Felt Suit with methyl bromide gas, removed the moth detritus, and placed it in a storage container fitted with Vapona strips. They then left it untouched in store, but monitored it in the hope that ‘textile conservators might eventually discover a suitable consolidant for such a severely deteriorated fabric.’10

Despite Felt Suit’s widespread damage, Tate did not consider the work defunct at this point. Richard Morphet advised Nicholas Serota that he did not ‘recommend destruction of whatever remains’ and, in fact, asserted, ‘appalling though the loss of our example is, it is extraordinarily eloquent in its present state. Eroded and horizontal, it gives a powerful sense of Beuys’s presence.’11 Derek Pullen, Head of Sculpture Conservation, confirms that Tate never considered disposal, relating, ‘there was no discussion … ever of disposing of it altogether. I think we just talked about retiring it to the archive, so that at some date in the future, if someone wanted to do something, then it was still there, and well looked after up until that point.’12 Rather than pronounce Felt Suit dead, Serota, Rainbird, and Pullen began discussing its possible restoration. However, the unfeasibility of this option quickly became apparent. Tate’s consultation with external textile conservators had already revealed that an appropriate consolidant for seriously deteriorated textiles did not yet exist, and that ‘any consolidant used … would alter the original colour, texture and appearance of the suit’.13 And Beuys’s employment of grey was precise. He declared, ‘With the greyness of felt I produce an anti-image. I evoke a world which is translucent and clear, maybe even transcendental, a very colourful world.’14 By introducing a consolidating adhesive, the artist’s intentions for the material and its colour would have been compromised, and the material’s potential for evocation extinguished.

Two other factors precluded the work’s restoration. First, the estimated costs for restoring Felt Suit were prohibitively high and, at that time, greater than the cost of replacement. Second, the necessary work would have been so invasive that Sean Rainbird concluded, ‘if we did reconstruct it – because quite a lot of the strapping was still good; it hadn’t been eaten away – it would be effectively reconstructing the work.’15 Therefore, Tate ruled out restoration. Having also excluded disposal as an option, the status of the suit remained in limbo.

In 1994, however, artist Jana Sterbak forced the issue of Felt Suit’s status within the collection. Sterbak proposed to Tate the idea of using the work as part of her installation for the 1996 exhibition Rites of Passage. The Director tentatively agreed, stating that the artist could show the suit in its conservation binding in a vitrine. Senior Curator Frances Morris advised Sterbak of Tate’s conditional approval, but added, ‘in order to make it clear that the suit is damaged and not a work of art, we will formally de-accession the suit so that it will effectively belong to our archive.’16 Significantly, Morris’s statement marks the first recorded instance of de-accessioning entering Tate discourse surrounding Felt Suit. As we have seen, Tate had heretofore demonstrated a reluctance to conceive of destroying the work, for both practical and philosophical reasons. Furthermore, UK law severely limits public collections from disposing of works, unless, for example, ‘their condition has deteriorated to such an extent as to render them “useless”.’17 Whilst the work had suffered serious deterioration both physically and, because of its inability to invoke the notions of warmth and protection intrinsic to Beuys’s use of felt, conceptually, its ‘uselessness’ had yet to be determined. On the contrary, Serota believed that, despite its damage, Felt Suit could make an ‘extraordinary contribution to [Sterbak’s] installation and to the exhibition as a whole.’18

The desire to support Sterbak’s ideas for installation, coupled with the need to preserve Felt Suit’s integrity, led Serota to consult with Heiner Bastian, Joseph Beuys’s former secretary. Bastian viewed photographs of the work and, in a letter to the Director, announced, ‘The Felt Suit by Joseph Beuys is completely destroyed.’ He went on to dismiss any possibility of the work’s future exhibition by declaring, ‘The suit was always meant to be a suit in perfect order without any wear and tear. It is unfortunately a total loss.’19

Tate now began its move towards formal de-accessioning. Serota contacted Eva Beuys, the artist’s widow and executor of his estate, and informed her that the museum had ‘with regret, decided to seek the permission of the Trustees to deaccession the work.’ He explained, ‘We have taken this decision because the damage appears to be irrevocable and we are advised that the work cannot be restored. For these reasons we do not feel we should display Felt Suit as a work of art within the collection.’20 In response, Eva Beuys asserted droit moral over the work, proclaiming:

It is with some difficulty that I state – in the name and from knowledge of Joseph Beuys – that for reasons to do with copyright and individual rights Felt Suit, belonging to the Tate Gallery, must sadly never be shown again in any location, on any occasion and in any context, however constituted, including for the purposes of study

For historical purposes it should continue to be recorded that the Tate Gallery possesses such a ‘Felt Suit’. For that remains an asset of the Tate Gallery.21

Droit moral, the artist’s moral rights, remain non-transferable and in effect throughout copyright. As executor of Beuys’s estate, Eva Beuys controlled the artist’s right to claim paternity over the work, prevent false attribution of authorship, and object to any distortion, mutilation, or other derogatory action in relation to the work that would prejudice the artist’s reputation.22 Ultimately, she maintained authority over the exploitation or display of Beuys’s work. Her statement, coupled with the provision within the 1992 Museums and Galleries Act allowing disposal of significantly deteriorated works, provided Tate with substantial legal support for Felt Suit’s de-accession.

According to conservators who witnessed Beuys’s reaction to damaged works, the artist would have corroborated the decision to de-accession. Christian Scheidemann recounts:

If … damage was unavoidable, he would have accepted it. With the felt suit we have to deal with an edition. The edition would carry a mission – and that was to keep the body temperature of the respective person and to keep him spiritually active. The suit was not about the decay … he was not at all interested in the uncontrolled decay – unless it was unavoidable.23

Hiltrud Schinzel concurs, stating that Beuys upheld standards of appearance for his works as part of his wider effort to raise public respect for art.24 In the end, Tate removed Felt Suit from the collection on 10 February 1995 and placed it in its Archive. Jana Sterbak received the loan of a Felt Suit from another collection for her installation. Tate acquired a second suit from the edition in 1998.

Does this mean that we can, at last and with certainty, classify Felt Suit as dead? Seemingly, as a work of art, the piece is defunct physically and conceptually. Nevertheless, Tate staff remain disinclined to declare it altogether dead. Serota has re-affirmed the museum’s intention not to destroy the work,25 while Richard Morphet described it as, ‘an accession with a history but no object,’26 an intriguing interpretation that assigns it, and removes it from, narrative simultaneously. Head of Sculpture Conservation Derek Pullen currently regards the work as ‘dormant,’ and counsels, ‘there is still a lot of information in that piece.’27 Even Eva Beuys maintains that Tate’s Felt Suit ‘still exists as an object.’28

It would appear that, although the work is no longer part of Tate’s collection, its remnants are suspended in conceptual and physical limbo. All parties agree that this carcass remains a powerful homage to an iconic artist, and acknowledge that it continues to function, albeit on an ancillary level. Although classified as an ‘archived object,’ it is stored alongside the rest of the collection within an insect controlled environment. It is observed, monitored, and continues to be listed as a ‘Vulnerable Item’ on the collection database. Like a recently unearthed archaeological artefact, it retains an essence of its original raison d’être but no longer functions as intended. Whilst Beuys himself contended that ‘all conservation is a form of self-comforting and self-deception, since all matter is destined to turn into dust,’ he also averred that, ‘what is indestructible is the spiritual substance’ of the work.29 That spiritual substance arguably infuses Tate’s archived Felt Suit.

In a correlative case, Eugen Blume, the Director of the Hamburger Bahnhof, argues that Beuys’s own spirit pervades Block Beuys, a seven-room collection of the artist’s works within the Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt. He declares, ‘The creator of this organisation, which escapes every known order, seems to be present among the objects with his hands and feelings on and in everything, like a tangible form that wanders hazily through the rooms.’30 Blume’s invocation of Beuys’s authority and authorship – his ‘hands and feelings’ – certifies the authenticity of Block Beuys as it stands today. Indeed, the artist repeatedly visited the Darmstadt Block from its establishment in 1970 until his death in 1986, recomposing the installations and objects each time. But the Hessisches Landesmuseum now has grave concerns about the current physical state of Block Beuys’s environment, prompting the museum to consider its renovation, and impelling renewed analysis of the constituent elements of both its authenticity, and its authorship.

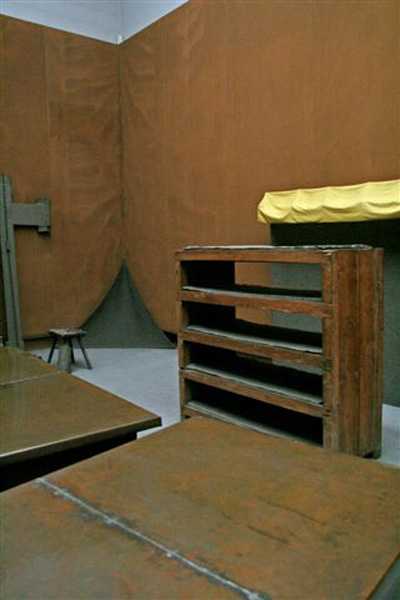

Virtually untouched since the artist’s death, Block Beuys’s objects and installations, greyish blue carpets, and jute walls have aged synchronically (fig.4).

Fig.4

Joseph Beuys

Block Beuys (Raum 1) (Room 1) (photographed 15 November 2005)

Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt

Photo: Wolfgang Fuhrmannek © DACS 2005

Degraded, they endure as visual reminders of Beuys’s original authorship, as well as his own mortality. The carpet has become grubby and worn. The once bisque-coloured jute has developed into a dark, dull copper, and bears noticeable abrasion and tearing. Yet the Hessisches Landesmuseum contends that rather than indicating the authorial imprint of Beuys, the uncurbed ageing of Block Beuys’s environment provokes many of its visitors to infer neglect.31 Moreover, the overall shabbiness and oppressiveness of the rooms seemingly prevents them from engaging with the installations therein, and with Beuys as an artist more broadly.32 As the entire museum is about to undergo renovation, the museum is considering whether to strip the Block’s original carpets and wall-coverings to reveal the floors and painted walls featured throughout the museum’s other galleries, in the belief that it could refresh not only Block Beuys, but also public reception of the artist himself.

Given the Block’s unaltered composition, however, the museum’s plans induce questions concerning the rooms’ implicit authenticity, and the potential ramifications of the proposed renovation. Does Beuys’s presumed authorship of the rooms extend to its carpets and walls? Are we to consider the seven rooms within Block Beuys themselves as installations whose legitimacy depends upon the objects and their environment remaining intact? Do the museum’s renovation plans therefore constitute a serious intervention on the part of its caretakers?

Plans for refurbishment, which include imperative upgrades to the Darmstadt Block’s climate control system, have existed for many years, but received financial backing only recently. Beuys himself left no instructions for the Block’s continued presentation and maintenance, though art journalist David Galloway has asserted, ‘Repeatedly he had expressed his wish that the components be seen together and remain together.’33 One of Beuys’s photographers, Manfred Leve, concurs:

The individual pieces and their arrangement as stipulated by Beuys are interdependent. The Block Beuys is not a depot for objects but rather a composite. It is not a conglomeration but an arrangement. An examination of the individual parts that does not take context into consideration would be wrong or incomplete and inappropriate to the work.34

The artist has left it to others to surmise from his words and actions how the Darmstadt Block’s context might be characterised, and whether its individual parts stretch beyond the objects themselves. These conjectures shall be explored more fully below. First, though, it is important to assess what is known about Beuys’s relationship with, and approach towards, Block Beuys. The objects came to the Hessisches Landesmuseum from both Beuys himself and collector Karl Ströher, who in 1967 acquired the majority of Beuys works exhibited at the Städtisches Museum Mönchengladbach, and first refusal of his future output, for DM400,000. Three years later, Ströher lent his collection, including the objects comprising Block Beuys, to the museum, which formally purchased it in 1989, thereby extinguishing the very real possibility of its relocation to another institution. ‘Nurturing this project like a private museum,’35 Beuys oversaw the appearance and arrangement of the Darmstadt Block from its inception in 1970, whereupon he professed a preference for the white walls distinguishing the museum galleries.36 And indeed, Leve’s recently published photographs of Beuys’s 1967 exhibition at the Städtisches Museum Mönchengladbach corroborate his predisposition for unadorned space, presenting multiple images of objects and installations, now housed within Block Beuys, conspicuously set against white walls and bare wooden floors.37 Nevertheless, after discovering that the rooms dedicated to Block Beuys contained greyish blue carpet and jute-covered walls, the artist accepted and even collaborated with the given space.

The nature of that collaboration manifests itself most overtly in Raum 1 (Room 1), where Beuys painted a yellow line between three objects, directly onto the carpet (fig.5) (the artist consciously did not label the exhibits within Block Beuys).

Fig.5

Joseph Beuys

Block Beuys (Raum 1) (Room 1) (detail, photographed 15 November 2005)

Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt

Photo: Wolfgang Fuhrmannek © DACS 2005

Although now faded and depleted by the dilapidated carpet, the hand-painted line gives credence to the view that Beuys explicitly authored all aspects of the Darmstadt Block. It both evinces his physical interaction with the room’s environment, and seemingly testifies to its impact upon his arrangement of the objects. Significantly, it also complicates renovation plans for the room. Replacing the carpet with flooring could be seen to compromise the installation’s appearance and authenticity by eliminating vital evidence of Beuys’s ‘hands and feelings.’ Whilst a replica line could be drawn onto parquet or concrete floors, for example, Beuys’s authorship, and thus his authorisation, would be absent from that particular element of the installation. As Dr Klaus-Dieter Pohl, the Hessisches Landesmuseum’s Curator of 19th- and 20th-century Painting and Sculpture, concedes, ‘I don’t know if Beuys would have made a line on parquet … you see this line on this carpet, but on the parquet it’s really another thing.’38

Additionally, the resulting physical changes to the room could not avoid impacting upon the Darmstadt Block conceptually. Visitors stepping onto the greyish blue carpet confront what Eugen Blume interprets as ‘the inviolable expanse of the sea. Here the ocean serves as a metaphor for the fullness and deep mystery of life into which man as a thinking being is placed.’39 For him, the Block’s seven rooms encompass ‘a cosmological work around a three-dimensional energy field in which everything refers to everything else and every thing speaks to every other thing.’40 Whilst the museum would preserve and archive the carpet, and could even reintroduce it into Raum 1 in future, modifying the walls and carpet would unquestionably disrupt this metaphoric import.

For Blume, Block Beuys’s context clearly extends beyond the objects alone. But were the ideas he propounds ever intrinsic to Beuys’s composition and conceptualisation of the Darmstadt Block? And does the declining physical state of the rooms impede those perceptions, and our experiences, of Block Beuys? Consider the carpets and jute walls today. The greyish blue carpet, perhaps evocative of the sea, has suffered extensive and highly noticeable staining and loss, thereby reducing both its potential for metaphor, and the visual fluency of the installations’ display.

The jute has darkened substantially, torn, and shows visible repairs (fig.6). Unlike the ageing objects within the rooms, whose material changes embody Beuys’s engagement with process, the decayed walls detract and distract from the carefully conceived installations, arguably blunting the artist’s presentation, and viewers’ reception of, the Darmstadt Block.

Fig.6

Joseph Beuys

Block Beuys (Raum 2) (Room 2) (photographed 19 July 2005)

Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt

Photo: Rachel Barker © DACS 2005

Perhaps because of the carpet’s pervasive damage, the Hessisches Landesmuseum does not regard cleaning to be an option. Its renovation plans could, however, result in honouring Beuys’s initial intentions for the rooms’ appearance by renovating or re-introducing the walls and floors present in its other galleries. For despite his acquiescence in Darmstadt – and there is anecdotal evidence that the artist ‘normally … accepted the situation in the exhibition rooms [as] they were’41 – Beuys’s intervention in the mounting of his 1979 Guggenheim retrospective revealed that his predilection for unembellished space persisted:

It is the first time the Guggenheim building is okay for art. I removed all fake walls, all ceilings which [sic] worked as a kind of decoration. I removed the blue pool-fountain and repainted it white … I gave it back a very original, simple, and sober character.’42

It is possible, and even likely that, given the opportunity, Beuys would have acted comparably in the Darmstadt Block. Yet the notion that traces of the artist’s, and the rooms’, history now reside within the carpets and walls convinces some to resist refurbishment plans. Hessisches Landesmuseum conservator Günter Schott, who assisted Beuys throughout each of his visits to the Block, concedes that its current environment may be the most historically authentic, ‘and if it’s new, well, its kind of aura is gone.’43 But conservation theorist Salvador Muños Viñas rightly points out that a work’s ‘successive conditions are all equally authentic, silent testimonies of its actual evolution.’44 He insists: ‘The present condition is necessarily authentic, and furthermore, its present condition is the only actually authentic condition. Any other presumed, preferred or expected condition exists only in the minds of the subjects, in their imagination, or in their memory.’45 He concludes by admonishing, ‘The belief that the preferred condition of an object is its authentic condition, that some change performed upon a real object can actually make it more real, is an important flaw in classical theories of conservation.’46 Muños Viñas’ discussion reveals the fallacy afflicting ascriptions of authenticity (and, correlatively, falsity) to an object, installation, or environment’s state. Following his conclusions, and in the absence of documented counsel from the artist, we would argue that the belief that rejecting change will render Block Beuys more real, and safeguard an assumed legitimacy, equally perpetuates a fiction at the core of classical theories of conservation.

By consistently re-visiting, re-composing, and thus re-authorising the Darmstadt Block, Joseph Beuys designated each of its successive states ‘authentic.’ He reinterpreted the Block with every visit, thereby emphasising its capacity for flux. ‘My sculpture is not fixed and finished. Processes continue in most of them: chemical reactions, fermentations, color changes, decay, drying up. Everything is in a state of change,’ he once famously announced.47 Notably, Günter Schott confirms that the artist would not have precluded intercession if material changes to an installation or object occluded its formative ideas: ‘It’s always the principal question, whether to preserve the idea or the material. But if Beuys were alive, he would intervene, perhaps, to preserve the idea.’48

For the Hessisches Landesmuseum, the level of deterioration possibly obstructs a significant amount of the concepts or readings that can be realised within Block Beuys. Visitors sometimes complain of neglect, and curator Klaus-Dieter Pohl offers compelling evidence that the decrepitude prevents their engagement with the artist and his work. He relates:

We are remarking that the reception of the Block Beuys … is lessening … especially in the younger generation. I have many guided tours here with students … and, some months ago, I had a tour with some … art students. … At the end, I asked them, ‘Now what do you think?’ And one girl said, ‘It’s only ugly. It’s only ugly.’ That was a big shock for me; I thought it over, because the first point is, they find it ugly, but they don’t make the step to go beyond this ugliness and to reflect, ‘Why is it ugly? What does it mean, ugly?’ … They don’t reflect, but it was a feeling … . And Beuys is not ugly; the forms aren’t ugly, so I thought, perhaps it’s really this whole situation [that] seems more drückend, more depressing.49

As the museum deems Block Beuys’s fundamental components to consist of its objects, vitrines, and installations only (a view it avers the artist shared), it submits that, rather than compromise the integrity of the Block, renovation and reinstallation could refresh, and make relevant again, artist and work alike.50 Schott, perhaps the Hessisches Landesmuseum’s most circumspect Beuys authority to participate in the renovation discussions, agrees. His contention that reinstallation will reinvigorate public engagement with the work provides a potent reminder of that notion’s centrality to Beuys’s practice and philosophy, and so to evaluations of Block Beuys’s continued integrity:

Beuys had installed these objects in his vitrines paying attention to the proportion of the rooms. That’s clear. And we don’t know what he would have done perhaps with white walls. But I think the most important thing is the proportion, not the colour of the walls. We don’t know in the end. But if we make it fresh and white, we are sure that this will be a new reception. A new reception will begin, and perhaps [be] more positive, or negative, that depends. For Beuys, it was worth more to have a negative discussion than no discussion51

It is in this spirit of candid yet informed debate that the museum has undertaken collaborative consultations with Beuys’s curators, colleagues, and estate in order to achieve sensitive and consensual resolution over the condition of Block Beuys. It exhibits an acute awareness of the complex conservation and philosophical issues attending renovation, as well as the potential rewards for Joseph Beuys and Block Beuys’s public reception. The Beuys Estate has confirmed that it was never the artist’s opinion that Block Beuys, in its entirety, was untouchable.52 Moreover, the museum has received backing from eminent Beuys colleagues such as Götz Adriani, the Hessisches Landesmuseum curator during Block Beuys’s installation. The museum recognises that either outcome – preservation or renovation – could estrange a sector of Beuys associates. What each sector must contemplate is whether that outcome will bring current and future audiences any closer to Beuys, his practice, and the Darmstadt Block.

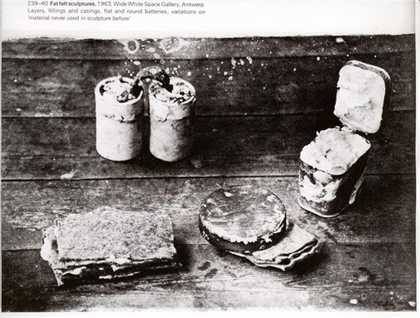

The Hessisches Landesmuseum’s confrontation with the particular philosophical and practical challenges that Beuys’s ageing works provoke are mirrored at Tate, who in 1984 acquired the artist’s 1963 work, Fat Battery (fig.7).

Fig.7

Joseph Beuys

Individual elements from Fat Battery 1963

Photograph taken in 1963, reproduced in Joseph Beuys, exhibition catalogue, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 1979 © DACS 2005

A hugely important work within the development of his examination of the meaning and purpose of sculpture, Fat Battery has undergone significant changes, calling into question its ability to communicate its conceptual, physical and aesthetic function.

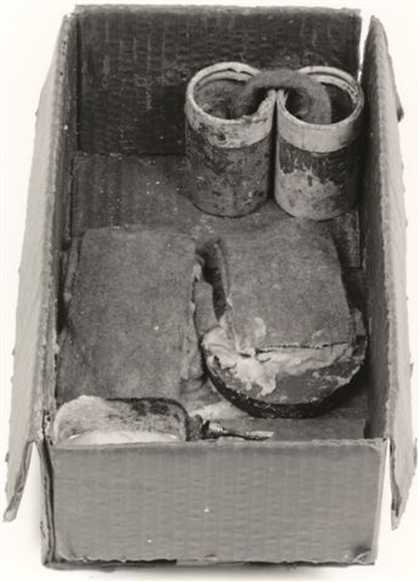

Fat Battery comprises a cardboard box supported by an underlying, hidden Formica tray (fig.8).

Joseph Beuys

Fat Battery (1963)

Tate

Fig.9

Joseph Beuys

Fat Battery 1963 (photographed in 1968 prior to acquisition by Tate)

Felt, fat, tin, wood and board

Tate. Presented by E.J. Power through the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1984 © DACS 2005

Inside the box, on the right, is an opened corned beef tin resting on its upturned lid, which Beuys himself repositioned after it had snapped off. The tin contains fat, specifically coconut oil margarine,53 now bleached white by ageing, and which, notably, has spilt over the edges of its container, saturating the surrounding cardboard (fig.9). Several sheets of felt interlaid with fat and placed on a round piece of metal lie in the middle of the box, whilst the left-hand side displays two metal casings that show marked corrosion on the outside. Each casing contains fat, and is linked with a strip of felt. All of the units within the cardboard box work in harmony to imply both a battery’s ability to harbour an electrical charge, and the generation of energy.

Beuys often engaged with electricity in his work, either using actual electricity, or suggesting its presence by wielding electrolytic or electrostatic processes, thus generating energy through the meeting of certain materials. He believed that the production of coldness and warmth, or polarities of energy, related to the human intellect, claiming, ‘you always have to think in terms of polarities, or forces, which are nothing other than awareness, presence of mind.’54 Furthermore, concepts of coldness and warmth were central to his Theory of Sculpture, which explicates changes of physical matter from a chaotic to an ordered state. For Beuys, material in its raw state is ‘chaotic’ and warm, whereas raw material that has undergone processing is ‘ordered’ and cold.55 Fat Battery’s fat content embodies Beuys’s theory through its ability to exist in both chaotic (when warm) and ordered (when cold) states.

Beuys’s reasons for utilising all of the materials in this sculpture are well documented. Fat, felt, and metal are materials now considered to be synonymous with Beuys’s sculpture. Each of these materials can insulate, produce or conduct energy, essential factors for an object representing a battery. Each sculptural unit – the felt and fat unit; the metal casings, fat and felt unit; and the tin and fat unit – individually and collectively denote the charge, discharge and recharge of energy.

However, a comparison between photographs of the object soon after completion, and its current appearance, discloses obvious and remarkable changes to Fat Battery, warranting an inquiry as to whether the sculpture continues to function as the artist intended. Whilst all of the materials used for this sculpture exhibit marked alterations, the most striking occur in the fat, felt, and cardboard box. The fat has liquefied and infiltrated the surrounding absorbent materials – the felt and cardboard box container – causing them to change colour and texture. The cardboard box is now quite soggy, and presents the threat of collapse. That threat has impelled Tate to review strategies for retaining the work’s conceptual and physical integrity.

Ironically, Joseph Beuys’s manipulation of organic and time-based materials both intrigued and alienated Tate in the 1970s, when it first contemplated acquiring Fat Battery. The history of its acquisition uncovers the museum’s awareness of the conservation and curatorial issues it has come to rouse. Fat Battery derived from a series of small units of work relating to Fluxus-type experiments that Beuys united in 1963, forming the sculpture as a whole. He retained it until 1967, when the Wide White Space Gallery in Antwerp obtained it.56 Over the following years, Beuys’s international reputation grew, and most major European galleries boasted significant holdings of his work. Whilst Tate had begun collecting work by Beuys, by the early 1970s this amounted only to a bronze object entitled Bed 1950. In order to represent his work more comprehensively, Tate curators and Beuys scholars believed that it was necessary to acquire works incorporating his signature materials of fat, felt and wax. This led Ronald Alley, the then-Keeper of the Modern Collection, to inquire of Beuys’s Düsseldorf gallery, ‘What chances are there of obtaining one or more of his works made up or [sic] unusual materials like felt and wax?’57 He reiterated this desire upon Tate’s purchase of Bed in 1972, stating:

We should like, when the opportunity arises, to buy further works of a different period and type, especially ones incorporating unusual materials like felt and wax. I realise that it is not easy to obtain works by Beuys of this type, but we should be grateful if you would let us know when you get some.58

Two years passed before the prospect of such a purchase materialised. In an April 1974 letter to Anny De Decker of the Wide White Space Gallery, then-Assistant Keeper Anne Seymour noted that Fat Battery (together with Das Erdtelephon, 1968) had been offered for sale six months earlier, and asked, ‘Are they still by any chance available? (Perhaps it is too much to hope for). We have at last come to the point where we are reconsidering our Beuys representation in earnest and would like to express our firm interest.’59 De Decker responded affirmatively and, presaging Beuys’s eventual placement of the work within a vitrine, proposed, ‘perhaps you could arrange yourself a case for the museum with different objects.’60

De Decker sent Fat Battery and Das Erdtelephon to Tate in June 1974 for the Board of Trustees to consider for purchase. Upon their receipt, Seymour declared, ‘they are both fine pieces and we are especially thrilled with the Fettbatterie.’61 But prior to the Board’s meeting to discuss Fat Battery, Tate Director Norman Reid warned the Trustees’ Chairman:

This piece has already changed considerably since it was made. My staff assure me that the artist says the changes do not matter or are even intrinsic to the work. I do not recommend spending £4,500 on a work which is almost impossible to conserve.62

In response, Beuys scholar Caroline Tisdall countered, ‘The idea of looking for ‘non-perishable’ works sounds sensible on the face of it, but in the case of Beuys it is rather complicated. As you know he has been using fat, felt, batteries etc, since the beginning of the Sixties, and these are the works that are in the European museums.’63 Nevertheless, the Board rejected Fat Battery, Das Erdtelephon, and another work, Eurasia 1966, on the basis of their impermanent materials. Richard Morphet advised De Decker that the Trustees ‘decided, instead, to seek to acquire works by Beuys, including drawings, which are less perishable than they considered these … works to be.’64 However, recognising the profound representational and referential importance of Fat Battery to Beuys’s 1962–4 Fluxus activity, the then-Chairman of Trustees, Ted Power, purchased the work himself, and offered it to Tate as a long-term loan.65

Within the next ten years, Tate’s holdings of Beuys’s work grew appreciably. In 1980, Sir Alan Bowness succeeded Sir Norman Reid, who had opposed Fat Battery’s purchase, as Director. Bowness was committed to developing Tate’s collection of Beuys’s works. Consequently, Tate acquired two vitrines in early 1984, in order to represent the artist’s most current work. Earlier in the same year, Beuys met with Bowness in Stuttgart, and suggested placing Tate’s collection of his work together in a display vitrine.66 His initial proposal to enclose Fat Battery, Felt Suit, Bed, and Tate’s collection of Beuys Blackboards from a 1972 lecture proved unworkable, so the artist agreed to come to London and install a vitrine using appropriate Tate pieces and recently made works from his own studio. In July 1984, Beuys placed Bed 1950, Fat Battery, and two new works – Bathtub for a Heroine 1950, recast in 1984, and Animal Woman 1949, recast in 1984 – in the third vitrine. He generously gifted these two works to Tate, spurring Ted Powers to emulate Beuys’s generosity and bequest Fat Battery to Tate as well. He declared, ‘The piece has been with the Tate since I bought it and I don’t want to break the “heart” of a vitrine by removing its “pacer battery,” so I have decided to offer it to the Tate now.’67 Displayed as an independent object from 1974 to 1984, it has since been shown only as part of a vitrine, and re-titled Untitled 1984. Tate believes that Beuys’s placement of the object within the vitrine rendered it permanently reinterpreted, and they wish to preserve it as such.

When Beuys visited Tate in 1984 and witnessed the effects of twenty years of ageing upon Fat Battery, he was pleased to note the small changes that had taken place. The fat had changed form, appeared to be more liquid, had bleached in colour, and had flowed from its original position within the metal container, saturating the cardboard outer container. It was also odorous, cracked, and had absorbed dirt from the environment. Despite these changes, Beuys exclaimed, ‘The fat should last as long as the Pharaohs,’ and remarked approvingly that Fat Battery now smelt exactly like an old battery.68

In order to assess whether the sculpture continues to function and behave as Beuys wished, it is useful to examine its materials, the degree of change, and whether Tate Conservation can accommodate those changes so that the intrinsic concept for this work is maintained. The most powerful alteration to the work occurs in the fat. Beuys first manipulated fat as a sculpting material in July 1963 for an action at the Rudolf Zwirner Gallery, Cologne, the same year he created Fat Battery. He explained, ‘My initial intention in using fat was to stimulate discussion. The flexibility of the material appealed to me particularly in its reaction to temperature changes. This flexibility is psychologically effective – people instinctively feel it relates to inner processes and feelings.’69 In addition to its material and representational properties, fat carried biographical significance for Beuys: his parents had wanted him to take a steady job at the local margarine factory in his hometown of Cleves.70 The reasons why Beuys chose coconut margarine for Fat Battery, other than for its physical and visual properties, are speculative. He stated only, ‘There’s nothing more banal than margarine; that shocks people.’71

The margarine so prevalent within the sculpture is primarily 80% fat and 20% aqueous materials, such as water or skimmed milk, within which are suspended additives such as colorants and preservatives. The fat element or glycerides in coconut margarine are mainly medium chain length saturated fatty acids such as lauric (50%), capric (6–7%) and myristic acids.

During manufacture, part of the fat element crystallises. The fat crystals form a 3D structure that houses the liquid oil, the aqueous material and additives. The amount of crystallised fat influences how paste-like the margarine is. Coconut margarine maintains a fairly solid and paste-like consistency as long as it is kept below 20 degrees centigrade. Agents causing deterioration of fat include heat, damp, bacteria and contact with some metals. The fat will harden and become odorous.

As Beuys’s visit to Tate in 1984 disclosed, the artist fully sanctioned the changes occurring within the fat. Even in its altered state, it manages to convey the ability to be both chaotic and static in nature, and its capacity for insulating and storing energy. Thus, the fat still resonates with Beuys’s original concept.

The artist apparently intended the fat’s infiltration into the surrounding materials, such as the felt and cardboard box. For him, this process was crucial to the ‘performance’ of the work. The infiltration further supported the chaotic potential of energy within the fat, and its ability to insulate the saturated material. To counter the chaos, the cardboard box ultimately controls, or brings order to, the action.

Fat Battery’s container box is composed of cardboard, a paper product that will become increasingly acidic, dark, and brittle, eventually losing its strength and collapsing. However, somewhat fortuitously, the cardboard box in this sculpture is being preserved by the infiltration of the margarine, sealing the structure of the card, and protecting it from harmful environmental forces of degradation.

Within the box lies one of its key sculptural units: two metal casings filled with fat and linked by a piece of felt. In a clean controlled environment, most metals will develop only a superficial tarnish but the acid components of some natural oils are corrosive. Fat Battery’s metal components have corroded noticeably since 1963, when photographs taken of the work revealed a much less tarnished surface. Their contact with the coconut margarine may, in part, have contributed to their corrosion. The green residue visible on the surface also suggests exposure to atmospheric pollutants. However, as metal is recognised as a good conductor of electricity, the casings continue to act as an appropriate vehicle for the expression of energy.

Felt features within a number of Fat Battery’s sculptural units. Felt is a fabric made of matted fibres, most usually wool, hair or fur, bonded together through the action of heat, moisture, chemicals and pressure. As Tate’s experience with Felt Suit proved, it is prone to insect infestation, particularly clothes and webbing moths, and easily traps dirt particles within its matted structure. Early photographs reveal that the felt in Fat Battery once boasted a fresh, aerated texture. Now, it is flattened and compressed due to the infiltration of fat, although this action appears to be complete, and the felt fully saturated. Importantly, the infiltration of fat was not unexpected, and may even have been necessary to the ‘performance’ of this work.

Fat Battery forms a collection of sculptural units connected and interrelated through their implicit ability to harbour energy. The conceptual interdependency of each sculptural unit depends upon their aesthetic and physical qualities remaining intact. Does the completion of an action such as saturation, or perhaps the conceptual or physical demise of one unit, thus have ramifications for the conceptual well-being of the whole? If so, the notion of replacing exhausted sculptural units of the Battery may be appropriate. Beuys was familiar with the issues of longevity in his work, as he illustrated with Capri Battery, 1985, a lemon attached to an electrical charger. He provided the sculpture with a set of instructions that advised, ‘Change battery every 1000 hours,’ thereby wittily signalling his awareness that organic materials are ultimately a limited resource. Similarly, Block Beuys conservator Günter Schott recalls that Beuys, referring to Site 1967, a felt and copper installation housed in Raum 2, advised him that, if necessary, ‘You can renovate the felt to keep the idea.’72

Significantly, however, Beuys was also known to display extreme protectiveness over the physical state of his works, insisting that change might be inappropriate. He famously sprayed the blackboard elements of works such as Eurasia 1966 with fixative in order to fix the surfaces and prevent damage and change.73 Given Beuys’s inconsistent stance regarding preventive treatment, Tate has reviewed Fat Battery. Its conservators and curators conclude that it still functions satisfactorily on a conceptual and physical level. However, the museum is aware that there will ultimately come a time when replacement of parts or the whole of this sculpture will need to be addressed. The imperative to discuss notions of replacement, reproduction, and renovation of Beuys’s work is crucial for its future care.

Tate is conscious of the need to ensure the appropriate preservation of this work in relation to how it interprets Beuys’s wishes, noting the outcry that ensued when institutions have taken the initiative to replicate, or reconstitute, parts of Beuys’s works when they ceased to function as intended. In 1977, for example, Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum authorised the ‘reconstitution’ of one of their Beuys works, Fettecke in Kartonschachtel 1963, after the gallery lighting melted the fat. The ‘fat’ was replaced with a less perishable concoction of 80% stearin, 17% linseed oil and 3% beeswax. Beuys was not consulted concerning this action, and the museum has received criticism from, amongst others, one of its present conservators: ‘In my opinion, what was done in 1977 was both too drastic and unnecessary. Looking at the records of the restoration and the pre-restoration photographs, I much prefer the damaged Corner of Fat to the present situation.’74

A similar approach to Fat Battery is unlikely. Tate values the original materials within this work, which it believes authenticate it despite, or even – given the primacy of energy to Beuys’s conception of this work – because of, its physical deterioration. The museum is committed to slowing down deterioration without physical intervention, and keeps the work in ambient museum conditions. Conservators regularly inspect the sculpture both on and off display, and restrict its movement, loaning it out only under exceptional circumstances. Much care is taken to maintain a clean environment within the display vitrine.

Through heedful and consensual curatorial and conservation practices, Tate and the Hessisches Landesmuseum are striving to demonstrate how Beuys’s work of the past forty years remains pertinent and dynamic today. Fluxus-related objects like Fat Battery interrogate the nature of art, oppose the idea of the uselessness of the art object, and reject the notion that art is a medium for an artist’s ego. These aims motivated Beuys throughout his career, and inspire much of contemporary art production today. To conserve those ideas, the form of Beuys’s works must survive physically and conceptually. Without the material form, we lose the idea. For Beuys, the two were indivisible. As Caroline Tisdall lamented, ‘It is a tragedy of Beuys’s work that the form gets divorced from the ideas. One bit gets left behind since no one can own the ideas. As they are transitory they risk being forgotten.’75 The cultural significance and contemporaneity of Beuys’s ideas prolong his legacy; it is our responsibility to ensure that the material objects support that legacy.