Foreword

Fig.1

Looking, talking, interpreting: learning in the gallery

© David Bebber

Since the inception of Tate Modern’s School Programme in May 2000, a range of new education initiatives has recognised the role of the cultural sector in supporting and extending pupils’ experience of the arts in formal education. New collaborations between DCMS and DfES, the Museums and Galleries Education Strategy, and the national Creative Partnerships programme bear witness to this upsurge in interest in this field. While this has been warmly welcomed by education specialists, attention has recently turned to the experience of learners whilst at museums and galleries.

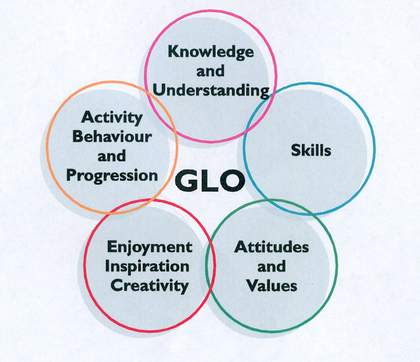

In 2004 the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (MLA) carried out the Learning Impact Research Project, out of which developed the Generic Learning Outcomes (hereafter GLOs) framework which the MLA is keen to see implemented across the sector.1 This autumn the Arts Council of England’s Visual Arts Department, in partnership with engage, the National Association for Gallery Education, will publish a paper which explores learning and teaching in the gallery and will propose a framework for contemporary gallery education.

The research that this paper reports on was initiated by the author to uncover the learning experience of our school visitors in order to better understand and develop the programme. The GLOs make the research particularly pertinent in that it enables a specific response to this framework, one borne out of the particularities of the gallery context at Tate Modern. While the research findings are broad they are necessarily more focused that the GLOs and as such will underpin future development of the Schools Programme as well as informing related debates in the field.

Helen Charman, Curator: Schools Programme, Tate

Discovery, disclosure or revelation is the means by which individuals encounter their creativity and the creativity of others. But most important for those working in arts education is the fact the creative process is nurtured by good educational practice.2

Introduction

This paper presents the findings from practice-based research into the experience of learners during visits to the Schools Programme at Tate Modern. The first section describes the research design. The second section outlines the research process and presents data analysis. The third section proposes a broad learning framework that characterises the learning experience. The fourth section considers the wider implications of learning in museums and galleries in the light of the GLOs put forward by Museums Libraries Archives (MLA).

Evidence gathered from various projects across the country indicate that learning in a museum or gallery enhances thinking skills, communication skills and self-esteem. A key question would be how does looking at contemporary art enhance thinking skills and in what ways do the learners alter their mode of thinking as a result of their experience in front of the artwork? As recently stated in a report by the MLA, ‘Museums are seen by all pupils of all ages as good places to learn in a way different from school, and teachers see museums as places where the enjoyment and inspiration experienced by their pupils acts as a pathway to learning’.3 What are the pathways to learning that a schools visit to Tate Modern might open up in the learner?

The internal context

A number of internal factors provide the context for this practice-based research project. One of these is to obtain the ‘insiders’ view of how the role of the Artist Educator and the practice of gallery education contribute to pupil learning. To date, there is very little literature that has been written from this standpoint. Given the growth and success over the past five years of the Schools Programme at Tate Modern, it seemed timely to reflect upon the type of learning taking place, how learning takes place and to make some of the learning processes more explicit, within the institution and beyond it. In essence, to ‘listen to ourselves talking about what we do’ within the field of gallery education.

The role of the artist educator

As a practising visual artist who has evolved, over a long period, into a professional Artist Educator through working in schools, museums and galleries, the author has a vested interest in analysing the roles and responsibilities that define this relatively new profession. In reflecting on the role of the Artist Educator in the learning process, it is necessary to ask if there are distinctive features inherent in the role. The Artist Educator is typically, but not exclusively, a fine arts practitioner (or a specialist Gallery Educator). She or he therefore embodies a specific form of engagement with art practice. Being a practitioner ‘on the inside of art’, implies a standpoint that comes directly out of some form of art practice and with the expertise of a creator. Whilst the main focus of this research has not been upon the role of the Artist Educator, it nevertheless has a direct bearing upon the nature of the dialogue constructed with the learner. Reflections on the role are interwoven throughout the paper. Further opportunities need to be made for Gallery Educators to analyse and record their practice in the field of gallery education. This seems like an unwritten text, yet to come, one to be written from within the profession as much as from outside it.4 The significance of the agency of the Artist Educator as a facilitator of learning in museums and galleries is overlooked within the MLA paper. It is therefore pertinent to make visible the distinctiveness and specialism of this role within the scope of this paper.

The following sections of the paper outline the role of the Artist Educator as researcher, the research questions posed and the methodology used to gather the research data.

The research design

The artist educator as researcher

Given that the researcher of this project is not a social scientist, the research project set out to excavate meaning and collect data using some of the processes more familiar to a fine artist. These included mapping out connections in a non linear fashion, borrowing references liberally from a wide range of different sources and disciplines, problem-solving in a heuristic manner and using open questions (whereas ‘true’ research might be defined by closed questions). Reflecting the experiential and multi-faceted nature of a gallery workshop in the practice-based research was itself a key consideration. If making art is a form of play with a purpose, then the artist consistently works with a very fluid set of rules, within which experimentation and risk taking have a high priority. Art as play has the nature of an open-ended enquiry, an ‘as if’ character, in that it ‘expresses something else through itself’,at times making use of metaphor, tricks, games and illusions.5 That making art also takes place in a realm where intuitive knowledge can be valued as highly as theoretical knowledge, sets up interesting parameters within which the practice-based research can operate.

The Artist Educator’s daily practice in the gallery could itself be compared to an on-going action research process, whereby the methodology of practical activities, games and strategies for learning are used and modified for use with different age groups, under different circumstances, with different artworks. The Artist Educator researches artworks in the collection in order to make learning activities in response to themes and issues, learning objectives and creative interpretations. Each activity devised by the Artist Educator is unique in the way in which it is used by him or her to facilitate learning about the chosen artwork. However, Artist Educators share one another’s activities and reinterpret or re-shape how they function in relation to their own style of working in the gallery. Thereby, a body of resources and expertise that evolves constantly in response to the changing nature of the collection shown at Tate Modern, is being created.

Research questions and methodology

The practice-based research proposed to address the following areas: to consider the impact of learning in the gallery and some of the outcomes; to assess qualitative shifts of perception in the learner; to measure hard and soft learning outcomes; to make a qualitative analysis of the learning framework in relation to modern and contemporary art in the collection at Tate Modern. Qualitative analysis considers the empirical experience (how learners understood their learning), as opposed to the quantitative and factual presentation of outcomes. The qualitative researcher seeks to understand and to relate the subjective understandings and the actions of those being studied. Qualitative researchers do not seek the ‘detached objectivity’ of the quantitative researcher. Rather she/he tries to engage practitioners in her/his research and to report findings in terms that are familiar to the subjects of investigation.

The research project was carried out over fifteen days from April to July 2004. All of the research was carried out within school visits to the permanent collection displays at Tate Modern. The Schools Programme at Tate Modern offers a menu of activities and a range of topics that support and extend classroom practice. Observation and documentation of the sessions taking place enabled a detailed analysis of the learning experience as it unfolds in either a one- or two-hour workshop. The learners sampled were taken from Key Stages 1-4 of the National Curriculum, children aged 5 to 16. Several of the Key Stage groups were observed twice, across different workshops and different themes. The research data was collected mainly through questionnaire, participant observation and discussion with learners (not principally with their teachers). Questionnaires were devised for the learners before they participated in a gallery workshop, in order to determine some of the expectations and attitudes they held toward modern and contemporary art. A proportion of pre-workshop questionnaires were sent to the school and filled out in the classroom.

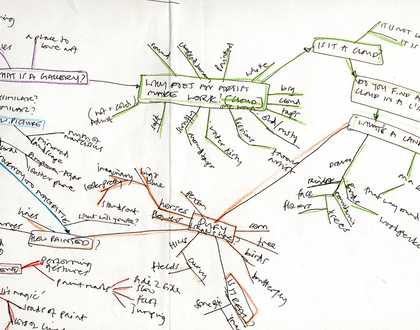

A follow-up questionnaire was presented immediately after the workshop in most cases. (Although the need for school groups to leave the building straight after the workshop affected the quality and the number of post-workshop questionnaires obtained). Short interviews and informal conversation with a sample group of children took place before and after the workshop. The long, slow escalator ride to the various levels of Tate Modern was a useful moment to gauge first responses and anticipation of what was to come, or to gather reflections on what had taken place. In the second phase of the research the technique of ‘mind mapping’ was used, both to record the gallery workshops and for learners to record theirs responses, instead of the questionnaires (fig.2). Mind mapping offers a visual method of recording information within a connected and associative framework.6

The original presentation of the research took a visual form (a PowerPoint display) as an attempt to reflect more closely the interactive characteristic of a gallery education workshop. The research was first presented at the engage international conference ‘Galleries Creating Learning’, in November 2004 held at Tate Modern.

Fig.2

Mind map from observation of a gallery workshop on the theme of landscape

© Michèle Fuirer

Approaches to learning at Tate Modern

The methodology developed by and through the Programme has been described in a paper by Helen Charman and Michaela Ross that provides a detailed study of the ‘Ways of Looking’ approach in practice during a Teachers’ Summer Institute.7 The methodology invites a form of learning that is characterised and underpinned by questioning as an active learning process; depth and breadth in looking at artworks; constructing plural meanings from artworks. Questioning is an active process that involves an exchange between learners. The need to draw on different frameworks of knowledge when looking at artworks inculcates depth and breadth, and brings to bear knowledge from an ‘expanded field’. Generating plural meanings from artworks is a challenging concept that ‘does away with’ the idea of a single truth and thereby creates a richness of experience. ‘The discovery of the true meaning of a text or a work of art is never finished: it is in fact an infinite process.’8

In a gallery workshop Artist Educator and learners move between images, words, gestures, objects and materials in making meanings from artworks. This process sets up a situation in which understanding is arrived at ‘through a continuous movement between whole and parts of a work, where meaning is constantly modified as further relationships are encountered.’9 There is the opportunity to encompass different learning styles and preferences within the framework of a gallery visit. This approach could be termed constructivist,10 in that the learners are constructing knowledge for themselves, both individually and as part of a group and in this way learning is not divorced from personal meaning or life experience. A feature of this model of acquiring knowledge is that, in rejecting didactic teaching, or transmission in a linear fashion from teacher to learner, the learner enjoys a heuristic engagement that takes them into discovery and self-motivation. Meaning becomes an understanding of the whole as well as the parts and the context.

A typical gallery workshop moves from first responses to more analytical enquiry, using a learner-centred and task-based approach. Before looking at samples of learning from a gallery workshop, the overall structure of a workshop is described. The basic components of a workshop might be: orientation – information about the collection and preparing to focus, using a warm-up activity or game; examining a work in focus – the whole group concentrates on one work, examining it in detail together, facilitated by the Artist Educator; small group work - discussion, tasks or activities carried out in small groups; whole group discussion – everyone feeding back on responses and discoveries about the artworks; followed by a plenary – to evaluate and reiterate key points of the learning experience.

A workshop may be structured to set up a proposition to be examined – for example, how do artists represent the idea of landscape, how do artists work with objects from everyday life, how do artists make images of history? It can also offer a theme that supports learning within the national curriculum – for example, the artist and society, picturing people, viewpoints or abstraction. When learners have an overview of the rationale of where they are going, they become more committed and more effective as learners.

Research process and data analysis

The research process recorded learners’ broad comments about their relationship to modern and contemporary art prior to the workshop and some of their expectations around learning in a museum. Secondly, it recorded the dialogic process of learning in a gallery workshop. It then recorded learners’ reflective statements about the learning process and how it had changed or repositioned their views on modern and contemporary art at Tate Modern.

Statements prior to the workshop

Responses to the pre-workshop question ‘Why do you like looking at art’ defined art in its broadest terms, describing it as a mode of ‘expressing yourself’, as a release from the perceived prescriptions or limitations of the written or spoken word. It was suggested that art presents a mode of expression that is both ‘mysterious and fun’, implying some sense of untold purpose and of enjoyment in the mystery. The separation of looking at art from making art is an interesting illustration/evocation of the split between thinking and doing that may occur within the interstices of the school curriculum itself.

‘I don’t like looking at it. I just like making art.’ Year 8 student.

‘Art is a way of expressing myself without words, but which can be mysterious and fun.’ Year 10 student.

‘To me art is a way of expressing yourself. I get to draw the things that I like.’ Year 10 student.

‘I like art. It’s always been a part of me. I used to go to the museum with my Nan and look at different art.’ Year 10 student.

‘I like drawing. If I am bored I draw to help me think’. Year 10 student.’

‘I get ideas from art.’ Year 10 student.

‘Art is expressing feelings, emotions and opinions, also, it can tell a story.’ Year 10 student.

The question ‘What skills do you think you might develop during the workshop?’ was designed to address the learner’s perception of skill in the context of a gallery learning. The perception of art-related skills that reside in technical mastery of ‘sketching’ and ‘detail and shading’ is a reflection of the strong emphasis upon technique in the teaching of art as a subject in schools across all of the key stages. However, there were a variety of responses that include a sense of the learner as a maker of art himself or herself: ‘getting ideas for my own art’.

‘I want to get ideas for making my own art.’ Year 9 student.

‘How to sketch a bit better.’ Year 9 student.

‘To know more about the famous artists here.’ Year 8 student.

‘I think I’ll be better at art like detail and shading.’ Year 8 student.

In the following section, key features of a learner’s experience are explored. It is by no means a comprehensive account of the scope of activity and discussion that take place within the gallery workshop.

The dialogic process

Dialogue in front of the artwork, a direct form of address, is at the centre of making meaning for the individual and the group. Talk opens up a space for the generation of new ideas and creates an active form of engagement with the artwork. Often, reading an artwork creates ambiguity and uncertainty in the viewer and the Artist Educator will acknowledge the instability and uncertainty. An intrinsic aspect of the facilitators’ role is to assert that knowledge may not be fixed or stable and to share with the learners the idea that learning is a process, that striving for meaning is a complex and difficult process. The reliance upon questioning as a means to debate requires subtle handling. Learners appreciate that they are required to think out their own answers, not to provide what the Artist Educator expects to see or hear. This requires considerable mental dexterity on behalf of the Educator. Knowing how to frame questions and how to work with questioning as a part of a dialogic process is a core skill within the Artist Educator’s range of skills. It is a challenge to provide the right amount of guidance, without providing too much direction. Direction is needed to help learners, but too much direction detracts from their sense of ownership of the learning.

Concerns about leaving meanings too open, uncertainty presiding over certainty, are assuaged by structured dialogue in the workshop that concludes and draw together what is being learnt. This, too, can be a collective enterprise with many voices contributing. The role of the Artist Educator is to facilitate the subtle process of arriving at concrete outcomes from a mutable process. From a practitioner’s point of view, this is analogous to the process of making an artwork, which may begin with a supposition, a hunch or a glimmer, but results in a tangible, viable outcome or product.

The dialogue below is taken out of context and should be read as a work (or workshop) in progress. There will have been dialogue and practical activities preceding and following on from each excerpt. The following extracts were drawn from a workshop for children aged 10-11 years, examining the theme of landscape in art, including the idea of landscape as a depiction of an interior world.

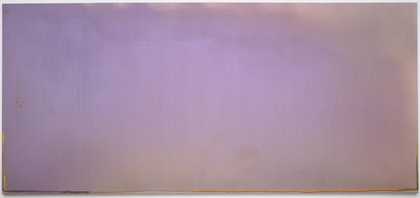

Jules Olitski

Instant Loveland (1968)

Tate

Artist Educator: ‘Why is this called Loveland [fig.3]? How would you show love?’

Pupils: ‘Make it red.’ ‘Hot.’ ‘I’d put big hearts all over.’

Artist Educator: ‘Yes. How would you paint love? Think about someone you love. Does this look like how you feel?’

Pupils: ‘No!’ ‘Yes!’ (a variety of agreement and disagreement)Artist Educator: (Pause) ‘It’s difficult, isn’t it?’Artist Educator: ‘What do you see here [fig.4]?’

Pupils from year 6: ‘Windows.’ ‘A football pitch.’ ‘The equals sign.’ ‘It’s to another world.’

Artist Educator: ‘If you could go through the window, what would it be like on the other side?’

Pupils: ‘Like stepping on a wobbly square.’ ‘Like a sponge.’ ‘I wouldn’t go!’ ‘You can’t go through, it’s blocked.’

Making connections with the artwork can be stimulated through a judicious use of resources. For example, word cues, handling objects or artefacts, quotations or photographic images culled from a wide range of sources. ‘Find a link’ activities have been devised by Artist Educators in order to generate both a connection and a range of polysemic readings through the activity. Oppositional thinking, articulating what something is or is not, enables a process of producing meaning through considering many possibilities. It provides a way to ‘indicate something ineffable by way of comparison to a counter-example’,11 for example, ‘it is rough and smooth’. This approach also fosters divergent thinking skills that may involve imaginative leaps, bold guesses, careful deduction and/or the use of a known fact. These cognitive activities make a constant redress to the visual examination of the artwork in question.

Fig.5

Fabric samples used to ‘find a link’ with Mark Rothko paintings

Artist Educator: ‘Look at your sample of material [fig.5]. Connect it with something you can see in the paintings. Ask yourself – what does it feel like, what does it look like, is it similar or different, in any way, from the paintings?’

Pupils: ‘Mine is fuzzy and a rectangle.’ ‘I can see through mine.’ ‘Mine has got rough edges and it’s smooth in the middle.’ ‘Mine is shiny. There’s a bit of shiny paint in the painting that reflects light toov ‘Er … did he use blood for the red?’

Reading two works together or looking thematically at a room are all part of considering how the framing context of the museum acts as a determinant of meaning. Activities such as re-devising the hang of a display, rewriting the labels for the artworks or finding new themes from works on display, direct the learner toward a critique of the values and cultural politics of the museum (figs 6 & 3).

Artist Educator: ‘Why did the curators put these two together?’

Pupils: ‘The texture is a bit the same.’ ‘Similar colours.’ ‘There’s no horizon in them.’Artist Educator: ‘Is it the same subject? Is it water?’

Pupils; ‘Erm… .’ ‘Yes.’ ‘No.’ ‘Yes.’ ‘No.’ ‘It’s more zoomed in.’ ‘It’s a rainbow reflected on water.’

Post-workshop dialogue

After the workshop, the impact on the learners’ experience was interpreted in terms of the broad definition of art, the acquisition of new skills and new learning, and the perceived use value of the experience to the learner. Learners’ statements about the meaning of art indicate awareness that interpretation is an active process in relation to making meaning: ‘Art is about the mind and what you see’. Perceiving art as a product of mind, of cognition and mental processing is a significant and insightful shift from the idea that art transmits itself to the viewer as an unmediated experience. That art can be in ‘deep detail’ suggests that readings are complex, that there are layers of meanings rather than one single meaning or truth. Accepting that an artist always makes work ‘for a reason’ is a significant step, particularly in relation to certain forms of conceptual or minimal art where the apparent lack of skill may well be equated with lack of content or meaning.

‘I am now questioning what art is. I learnt that there are more things to art than paintings.’

‘Art is about the mind and what you see.’

‘It represents the whole story. It’s in deep detail.’

‘Modern art is painted for a reason – the artist’s view of something or their emotions.’ Year 8 student.

In response to a question about new learning and learning new skills, learners’ comments indicate an expanded view of the role of technique in an artwork. A more complex reading of the relationship between form and content in the artwork seemed to emerge after the workshop, together with an enhanced vocabulary.

‘There is loads of different techniques of how to use a paint brush.’

‘You can represent whole situations or memories with symbolism and colour. Pictures do not have to be literal.’

‘Before, I thought artists did rough copies and then re-painted them on clean canvas.’

There is an acknowledgement that personal interpretation and those generated through a group discussion are part of a dialogical relationship in which many voices contribute to the sense. ‘Comparing’, ‘refining’ and ‘looking at things from another angle’ is a range of skills that infer complex modes of thinking and analysis as a part of deep learning. For example, deep learning is characterised by relating knowledge from different sources, where surface learning would rely upon using information that will relate to one instance only.12 When questioned about the use value of the experience some learners commented that they had got inside the viewpoint of the artist or felt they knew how to ask questions of the art.

‘If you study the art, you can understand what the artist wanted you to see.’ Year 9 student.

‘Discussing the meaning of the art in question and comparing it with your own and refining these ideas.’

‘I know what to look for when I see modern art – it’s helped me look at things from another angle.’

‘Discussing art helps to see other people’s ideas.’ Year 8 student.

Learning frameworks

Analysis and interpretation

Analysing data of this nature is an intricate process, and suggests the need for a longitudinal study to track the shifts in learners’ perceptions over time and applied to the classroom setting. Much of the data collected warrants further study. However, a broad set of characteristics of the learning experience can be suggested:

- looking as a skill

- learning as a social and dialogical process

- the value of experimentation

- interpretation as a creative act

- engaged responses

- engagement with the Artist Educator

Looking as a skill

The adage ‘looking is easy, seeing is not’ is seminal to the work at the heart of gallery education. Or, as delightfully expressed by Artist and Educator Jefford Horrigan, ‘A glance is to make sure there are no tigers in the room – there are different ways of looking.’13 Learning to look to a purpose and with understanding is a skill and can therefore be taught, practised, revised, reviewed and developed over time. Looking as an active process intersects with talking, questioning, listening and making as a part of an interconnected mode of response to the artwork in question. The process of looking is concomitant to making meaning from the artwork, in that close looking encompasses formal analysis. Many Artist Educators will be heard to say that ‘we look and look again’. The perception and identification of the art object – whether painting, video, installation or text, in its specific detail has to form the basis for all subsequent activity around it. Therefore, a constant checking process takes place in the learner between what is materially seen or known, formulating an idea and forming an interpretation.14

Learning as a social and dialogical process

It can be acknowledged that individual learning takes place in a specific social, cultural and historical context. This has to be accounted for in the way in which the Artist Educator works through responses with a diverse group of learners and in the accommodation of their differences. Learners clearly bring prior knowledge to viewing art and with this their own mental knowledge maps that work dialogically with the processes of interpretation. Therefore, the interaction with others’ voices and the making of multiple interpretations is an inherent characteristic of gallery-based learning. The Artist Educator fosters connections between the learner and the art object, and the art object and its wider context in order to preserve a continuum between making meaning at home, school and in the gallery; a continuum between things on the page, screen or gallery wall; between things seen, known and felt. Veronica Sekules states that, ‘as a locus for education which has both formal and informal elements, the museum has the capacity to bridge the cultures of artist and school in a way which takes the spotlight away from the dominance of their differences (…) It can become a territory for educational exchange and experiment where questioning and personal development is the norm.’15 Indeed, current policy development highlights the role of the museum as a social meeting place, ‘as a container for cultural discourse other than cultural artefacts.’16 Informal learning opportunities in the museum, such as short courses, study days, seminars and talks contribute to the opening up of the museum as a public space. Informal learning remains free from the abstraction of imposed standards and criteria or specified learning outcomes. The very texture of informal learning is that of experience and self-development.

The value of experimentation

The value of play and of experimentation is distinctive in gallery-based learning. If art is play to a purpose and the artist a type of trickster, a creator of games and illusions, can learners and viewers also play with meaning, ideas and interpretation? The concept of experimentation and haptic learning is a form of making and re-making knowledge for the learner. The use of tactile and sensory involvement, handling objects and a ‘hands on’ approach enhances the opportunities for the learner to make connections between doing and thinking.17 Indeed, there is little point to activities in which hands on is not connected to ‘brains on’.

In the artist, intuition and implicit knowledge are highly valued as a working skill, and so for the viewer or learner, too, the origination of thought can come from a hidden space. Within this experience, perception and intuition take on the guise of a different type of knowledge. In a gallery workshop, the learner is invited to step inside the framework of play, to take risks and think divergently, using intuition, as well as reflection and reason as part of a learning experience. This definition of play is not separate from, rather it is harnessed to, the process of meaning making and interpretation.

Interpretation as a creative act

Fig.7

Children in small groups sorting and ordering sets of an image-based resource as a constructed form of play in order to generate new thoughts and perceptions about artwork by Tony Cragg

© David Bebber

In arguments for increasing access to museums and galleries enhanced creativity is frequently cited as the chief benefit or outcome of time spent either participating in or viewing art. Less frequently cited is a useful definition of the term creativity as it is applied in the context of learning in a museum.18 Creativity has a workable, ‘no nonsense’ definition in the National Curriculum: ‘imagination and purpose (not totally off the wall, having a purpose in relation to something, being directed toward achieving something), has an outcome; originality (new to the learner), value (evaluate the worth, validity, usefulness of the creative idea).’19 The emphasis upon demonstrable use value and the need for an outcome suggests some anxieties about art for art’s sake. However, defining originality as something ‘new to the learner’ is useful, since it neatly bypasses the trope of the artist as a creative genius pouring forth an endless stream of works of originality. From a skills-based point of view Gavin Jantes has noted that, ‘Creativity is an imaginative form of problem solving … Creativity is a process: the transformation of abstract ideas into material objects via the few skills one has – and the learning of new skills’.20

Creativity re-formulated as ‘creative thinking’ becomes all the more powerful when allied to analytical and critical thinking skills. Creative thinking skills enable learners to generate and extend ideas; to suggest hypotheses; to apply imagination; and to look for innovative outcomes. The combined forces of these two skills would suggest that, in the context of gallery education, to make an interpretation of an artwork is a creative act in and of itself. In addition, engagement with the artwork and the ensuing interpretive experience can be thought of as a form of practical experimenting. Testing knowledge in the here and now of the encounter with the art work suggests that gallery education provides a distinctive form of learning akin to action research whereby the learner may formulate new models of understanding whilst actively engaged in the learning situation.21

Engaged responses

An engaged form of learning is one where the learner embarks upon a circular process of making meaning: posing questions, trying out answers, re-formulating the questions and remodelling the answers. Understanding happens when new information or experiences can be set against the framework of patterns of previous learning. In Kolb’s model of experiential learning the learner moves in a cycle from concrete experience to observation and reflection to forming abstract concepts to involvement in active experimentation – that is, from feeling to watching, thinking and doing.22 This is a type of learning that involves direct encounter with the phenomena being studied, rather than thinking about an encounter or considering the possibility of an encounter. This heuristic form of learning positions the learner as a self-motivated discoverer of her or his own learning.

Fig.8

A direct encounter with artwork in the gallery provides an opportunity for drawing to be used as a critical tool to investigate the process of looking

© Rachel Moss

Drawing provides just one example from a range of activities devised to promote engaged learning in the gallery. Drawing charts the very process of looking; you draw in order to see how you look. Drawing also extends an understanding of the relationship between form and meanings, the mark-making language on paper is used to analyse and describe how the form works to communicate ideas about its purpose and its sense of ‘objectness’.

In another guise, drawing can be used as a critical tool to investigate a concept or an idea, for example, mapping thoughts, creating a spider diagram or any other form of visual annotation of the thinking process. Drawing creates a dynamic interplay between word and image and provides evidence of visual thinking. In this type of engaged activity, the learner in a gallery is opened up to a far broader realisation of drawing than the more familiar copyist role usually assigned to it. The importance of learning through art as an immersive experience should not be underestimated. It may be that during this experience we momentarily ‘lose our co-ordinates’23 in order to find a new position from which to view and to understand our relationship to the world.

Engagement with the artist educator

The role of the Artist Educator has been referred to in this paper as that of a specialist, that is neither exactly teacher nor purely an artist. When learners enter the learning framework it is likely that their perception of the person leading their workshop is one of teacher, expert or ‘significant other’, that is, a person who has all the answers to their questions. However, the Artist Educator promotes reflective dialogue and is likely to ask more questions even than the learner. In a learning situation where the dialogic process takes precedence, everyone contributes to meaning making. Contributions are regarded as resources to be used constructively and collaboratively within a shared culture of learning. In her influential writing on engaged pedagogies Bell Hooks suggests that the relationship between learner and teacher ‘does not simply seek to empower students. A classroom … will also be a place where teachers grow and are empowered by the process … That empowerment cannot happen if we refuse to be vulnerable while encouraging our students to take risks’.24 The implication that co-learning takes place and that the learner may shape and inform the learning of the Artist Educator is a critical feature of gallery education. The relationship between Educator and learner can be very close, even to the point of collaboration. As an extension of this collaboration, the Educator embodies the values they wish to see develop in the learner, that of self-evaluation, self-esteem and the building of self-knowledge.

The space of learning within the museum or the gallery then becomes a significantly different space to that of the lecture hall or the classroom. A comparison may be made with the art school (or art classroom) whereby ‘teacher and student are on the same level, both are talking and the visual is predominant. In the studio situation the experimental character of art creation can be explored, mind and hands are actively occupied’.25 The encounter with the Artist Educator presents an opportunity for the learner to model a conversation with an artist. The significance of this modelling process may enable a closer understanding of the artist’s intention ‘what the artist is about’, than a view that purports to tell the learner why the artwork is historically important in the canon of art historical knowledge.

![]() Wider implications

Wider implications

In 2004 the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (MLA) published a generic framework for measuring learning outcomes as the result of a large-scale study of school visits to museums, libraries and archives in England. This section considers learning outcomes at Tate Modern within the context of this report.

The introduction to the report states that the ‘The research provides a baseline for future research’, indicating its centrality to thinking and policy around learning in museums and galleries.26 The report states the objectives of the research were to ‘describe the outcomes and impact of the investment in the new museum educational programme. By focusing on teachers’ and pupils’ view of what the pupils learnt, it shows how museums are achieving government targets through using museums to inspire learning and to increase pupils’ confidence and motivation’. The report heralds an endorsement of the value of learning in a museum or gallery and places this type of learning at the forefront of pedagogical development. It is a document that demonstrates the depth and breadth of many different types of learning in a range of institutions. There are a number of difficulties, however, with making a fit between the generic classification of learning outcomes and the specifics of different cultural contexts. The outcomes of a visit to a museum of science cannot be expected to be the same as a visit to a contemporary art museum. Even though the approach to learning may bear many of the same characteristics (such as learner-centred and hands-on), the learning objectives and targets may diverge considerably. In explaining the need to develop a set of generic learning outcomes the report states:

The conceptual framework used to shape the research is based on the idea of Generic Learning Outcomes. This is a new approach in museums, it is informed by contemporary learning theory, and has been tested and validated by museums, archives and libraries across England.(…) Each individual learns in their own way, using their own preferred learning styles, and according to what they want to know. Each person experiences their own outcomes from learning. But individual learning outcomes can be grouped into generic categories and these can be used to analyse what people say about their learning in museums.27

Grouping individual learning outcomes into generic categories consequently raises the important question of what categories are set and what they infer, since by their existence they establish a level of consensus about what learning outcomes are.

Fig.9

The Five Generic Learning Outcomes described by MLA

© Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (MLA) 2005

Some of the specific learning outcomes described in this paper seem to be weakened and diminished through the creation of Generic Learning Outcomes. Many of the specific skills and complex types of learning are overlooked, though creativity is championed above all else. The three learning outcomes that are looked at in more detail below – Enjoyment, Inspiration and Creativity; Increase in Skills; Increase in Knowledge and Understanding – indicate some of the issues inherent in defining learning by generic outcomes.

Enjoyment, inspiration and creativity

When teachers were asked to rank the GLOs in order of importance to them as the outcome of a museum or gallery visit ‘Enjoyment, Inspiration and Creativity’ rated most highly. While it is essential for most teachers that museum visits are linked to the curriculum, it is clear that this on its own is not enough. Creativity, as defined by the report, is a mix of ‘having fun; being surprised’ and ‘innovative thoughts, actions or things … exploration, experimentation and making; being inspired.’ The report uses example statements from teachers to illustrate creativity in a learning experience: ‘The children enjoyed making pots and looking at the skeleton at the dig. They also enjoyed the jewellery making.’ ‘Being inspired’ is illustrated as ‘the children had not realised that the people of Taunton were Victorians.’ The cause of the disparity between concept and example is that ‘creativity’ and ‘inspiration’ necessarily mean different things when applied to different cultural contexts. The specifics of the context need to be analysed, as much as the content of the learning.

Increase in skills

Although the report states that ‘the museum visit has the power to jolt latent learning capacity into action; it works as a catalyst to spark curiosity; and the experience is so powerful that it can be recalled and reused for a long time afterwards,’28 in the process of ranking outcomes, ‘Increase in Skills’ is ranked last place. Soft outcomes (attitudes, values and emotions) and hard outcomes (knowledge and understanding, making sense) are blended together in a manner which has a tendency to level out the significance they may hold in the learning experience overall. Physical skills such as ‘dancing, manipulation and making’ are cited under ‘Skills’, whereas ‘drawing and painting’ are cited under ‘Enjoyment, Inspiration and Creativity’. Soft skills such as communication and social skills are rated as a ‘very likely outcome’, as are thinking skills, but no particular distinction is made between them. The skills analysed in this paper, such as looking, interpretation and meaning making are not identified by their key role as such. If there is no specific demarcation of the higher order thinking skills developed through learning in a museum, then some of the notion of putting a value on learning is lost.

Knowledge and understanding

‘Learning about a subject’ and ‘subject specific facts’ were regarded as the most likely knowledge-related outcome by teachers, as a result of the museum visit. By defining ‘knowledge and understanding’ through ‘subject specific facts’ much of the value of process based learning is overlooked. Is ‘subject specific knowledge’ the most appropriate way to define knowledge in relation to looking at modern and contemporary art? If gallery learning is an immersive experience of the kind described in this paper, then subject specific facts are not one of the high priority outcomes. Which is not to argue that facts are considered unwelcome, rather that the way in which facts are garnered is more likely to be a product of the whole learning experience, than a single target of it. As has been discussed in this paper, the gallery education learning framework uses the learners’ prior knowledge to make connections and relationships to new learning. It therefore deepens knowledge in a holistic and sophisticated manner.

The establishment of Generic Learning Outcomes is one element toward identifying the ‘latent learning capacity’ potential variety of learning outcomes across museums and galleries. Future research will necessarily complicate and enrich our understanding of how and why people learn from collections of modern and contemporary in particular. This paper has addressed learning within the defined community of school-age learners. The principles and concepts of the learning methodology, however, are also deployed with adults and a wide spectrum of learners. Each of these bodies or communities of learners maintains a highly individual learning profile and each is driven by varied sets of needs, motives and desires. Therefore, fine distinctions need to be made about types of learning and learners in relation to different types of cultural institution. There is no case to be made for a ‘one size fits all’ approach in this highly complex and individuated field of learning.