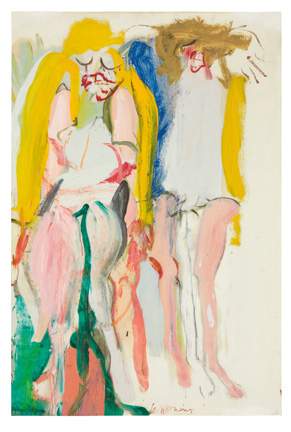

Fig.1

Willem de Kooning

Women Singing II 1966

Oil on paper on canvas

914 x 610 mm

Tate T01178

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The two figures in Willem de Kooning’s Women Singing II 1966 (Tate T01178; fig.1), painted in large, fluid strokes, fill nearly the entire surface of the large piece of paper. Their messy hairstyles reach to the upper edge, the left figure’s brown bouffant appearing to continue off the top of the sheet. Hair and rubber-like arms reach the right and left edges, and the women’s sketchily rendered feet almost touch the bottom perimeter. Some space exists around and between the women, keeping them from entirely melding into one another. Greens and blues mostly fill these intervening spaces, but sometimes the paper remains blank, as can be seen in the top right corner above the right figure’s head and parts of the lower right corner near her feet. The result is a shallow space, without identifying features, and the women seem almost pressed against, or onto, the surface of the paper. As in so many of de Kooning’s paintings, figure and ground are difficult to demarcate and instead appear as if all of one piece.

Fig.2

Willem de Kooning

Singing Women 1966

Oil on paper on masonite

914 x 610 mm

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.3

Willem de Kooning

Women Singing I 1966

Oil on paper on board

914 x 609 mm

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

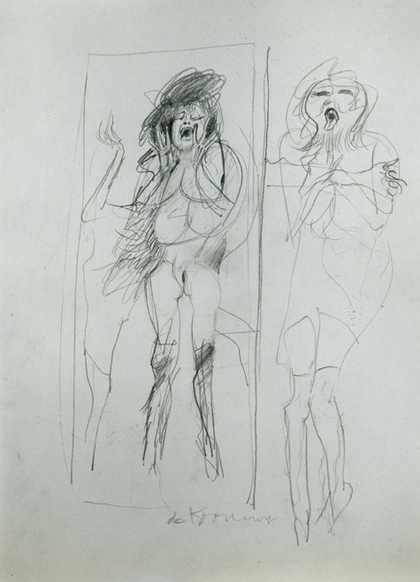

In early 1970 Tate’s Keeper of the Modern Collection, Ronald Alley, wrote to de Kooning’s dealer Xavier Fourcade about ‘the theme’ that de Kooning might have had ‘in mind’ when he created Women Singing II, then newly acquired by Tate, and two other closely related paintings (Singing Women 1966 and Women Singing I 1966; figs.2 and 3).1 Fourcade responded rather generally, writing, ‘I have always been told by Bill de Kooning that this image of singing women is a memory of pop singers he saw on television’.2 De Kooning loved watching popular programming and variety shows on TV, a pastime enjoyed in the evening after a day’s work of painting in his large studio in Springs, East Hampton, on New York’s Long Island.3 De Kooning’s friend and foremost champion, the art critic Thomas Hess, corroborated Fourcade’s statement by describing some of de Kooning’s favoured subjects garnered from evening programming during the mid-1960s: ‘He especially enjoys the young dancers, Go-Go girls, and their gestures are caught in a number of drawings: knees spread, arms pumping, pelvis tilted, all rocking with that wide happy American smile. There are also some drawings of TV singers, hitting the hard note, their hands pushing the sound as it comes out of their mouths’.4 The women in Women Singing II seem to be pushing for that hard note. While this description of the subject matter seems straightforward enough, a related pencil drawing with a very similar composition and a different title (Screaming Girls c.1966–7; fig.4) suggests that the women could just as well be screaming – perhaps teens yelling for the newest pop sensation.5 With these rather generalised descriptions, however, it is difficult to say whether de Kooning was recalling a specific performance on The Ed Sullivan Show or American Bandstand, or conflating several performances across shows. Perhaps de Kooning had in mind a scene from the contemporary musical Cabaret, first shown on Broadway in 1966, which he might have seen or heard about from a friend.6 Given what we know of de Kooning’s artistic process, the imagery of Women Singing II is unlikely to come from any single source but rather several different ones. Suffice it to say, however, that these women are at one with mid-1960s popular culture, infused with a lightness and gaiety.

Fig.4

Willem de Kooning

Screaming Girls c.1966–7

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

‘Intimate proportions’

The woman on the left has her eyes closed, her long eyelashes pointing downward. Her mouth, heavily lipsticked, opens wide to reveal a smaller mouth with teeth inside. Her hair, initially painted as long and blonde and later changed to brown, sits in a bouffant on top of her head. Her arms, rendered by two long strokes of paint without any anatomical indication of hands or bodily attachment, reach up, and the areas of paint that would be her hands frame her face on either side. On close inspection one can see that de Kooning painted the figure’s left arm with a pale peach coloured paint over what was at first a section of the figure’s hair. The paint here is rather thick, even creamy, and this stroke appears to be one of the last placed on the paper.

Here, in a single brushstroke, de Kooning made hair into arm, suggesting the mutability, or interchangeability, of body parts. In a handwritten note from sometime in the early 1950s de Kooning described this interchangeability when explaining the idea of intimate proportions: ‘With intimate proportions I mean the familiarity you have when you look at somebody’s big toe when close to it, or a crease in a hand or a nose – or lips or a ty [thigh]. The drawing those parts make are interchangeable one for the other and become so many spots of paint or brushstrokes’.7 De Kooning’s statement reads a little awkwardly. The word ‘proportions’ does not seem quite right; perhaps another way to formulate the idea would be with the word ‘scale’, as he is talking about looking at something up close. The scale of body parts changes depending on whether one is observing from afar – sketching a live model, for instance – or one is in intimate and familiar contact with another’s body parts, as a lover might be. De Kooning was not interested in the scientific or anatomical study of body parts – shoulders and knees, and how they attached to other body parts, flummoxed him – but rather describes a subjective study of those parts. When looking so closely, so intimately, it is as if the looking becomes detached. What de Kooning described is looking so closely at a thigh or toe that that body part becomes something else: a shape. Once the parts are rendered as drawings (the passive tense here seems appropriate given the way that de Kooning formulated the idea) they become shapes that can be rotated, flipped, reduced and enlarged, fitting together in a myriad of ways. With his statement de Kooning makes it clear that as much as we focus on the image or representation of the two women, they are, in fact, just ‘so many spots of paint or brushstrokes’. The shape of hair and the shape of an arm, both rendered easily by a single stroke of paint, become interchangeable.

The left figure’s torso, rendered in white paint, is not well defined, and a red line painted horizontally across her pelvic region could indicate her sex or, just as easily, the hem of a very short dress that twists around her body. Her legs, too, seem to twist in space, with her right leg seen in profile: the knee on the left and a well-defined calf on the right. The knee is indicated by what appears to be charcoal smudged or scraped over, creating a modelled effect and giving the knee a dimensionality that the other body parts lack. This dimensionality, however, is counterbalanced by the fact that de Kooning created the legs not by painting them but by outlining them. Bare paper, rather than creamy pale peach, makes up the flesh of the legs, initially outlined by the blues and greens of the ground and later by thinly painted brown strokes. The woman wears high heels, indicated by the exaggeratedly pointed nature of her feet. One can see the high heel of her left foot simply indicated using a blue stroke.

Like her companion, the woman on the right also has her mouth open and her arms raised with her would-be hands framing her face. Her hair is long and blonde, and her eyes are open, floating in her mass of yellow hair. She seems to wear a short skirt that exposes her slender, pale legs, although given de Kooning’s penchant for multiple possibilities, what I take to be a dress could also be her buttocks, suggesting a nude figure twisting in space. She wears only one high heel. Her legs, rendered by two downward strokes of pale peach, conjoin near the pelvic area, and her shoeless leg abruptly ends. The paint thins as it reaches the ‘ankles’, suggesting that de Kooning painted each leg with a single stroke from top to bottom. Curiously, de Kooning painted another pair of legs in a similar manner slightly to the right of these ones, trailing off the paper. The interchangeability of hair and arms, the lack of distinction between hem lines and anatomy, and the one-stroke arms and legs all remind the viewer that he or she is, in fact, looking at paint on a surface and not simply an image of women singing or screaming or standing.

Fig.5

Willem de Kooning

Woman I 1950–2

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.6

Willem de Kooning

Woman III 1952–3

Collection of Steven A. Cohen

Photo: Gagosian Gallery

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

De Kooning explored the female figure – and how to paint it – throughout his long career. Women Singing II differs in form, colour and mood from de Kooning’s earlier, more notorious women from the early 1950s. Woman I 1950–2 (fig.5) and her friends caused much outrage in the art world when they were shown at the Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, in 1953 and brought charges of misogyny against de Kooning that persisted for decades.8 Some critics understood one of them, Woman III 1952–3 (fig.6), as proof that de Kooning hated women because he had supposedly depicted three bullet holes across her chest with large red daubs of paint. In response de Kooning quipped, ‘I thought it was rubies’.9 Elaine de Kooning, the artist’s wife, set the record straight when she wrote to her friend, the artist William Brown, detailing the various responses to the 1953 Janis show: ‘The bullet holes, be it known, are very chic rubies which stick to the skin unaided or abetted by pins or chains – a device de Kooning saw in [the magazine] Harper’s Bazaar and never forgot’.10 De Kooning attempted to dismiss the charges of misogyny over the years. In 1964 he told critic George Dickerson:

In a way I feel that the Women of the ’50s were a failure. I see the horror in them now, but I didn’t mean it then. I wanted them to be funny and not look so sad and downtrodden like the women in the paintings in the ’30s so I made them satiric and monstrous, like sibyls.11

The women of the 1950s were born from pin-up girls and Hollywood starlets, from women fighting their way through the bargain bins at department stores and wearing their Sunday best as they strolled down the streets of Manhattan.12 De Kooning also thought the women had something of the ancient idols in them, embodying a power and presence.13 The women of Women Singing II do not have the gravitas or fierceness of the women of the 1950s, but they share the relation to popular culture.

Ambiguous spaces and seductive surfaces

Fig.7

Willem de Kooning

Woman, Sag Harbor 1964

Oil and charcoal on wood

2032 x 914 mm

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Born in Rotterdam in 1904, de Kooning came to the United States in 1926 as a stowaway. He told Dickerson:

I used to love to see the old American Western movies in Rotterdam – ones with Hoot Gibson and Tom Mix. Today the Westerns are too influenced by Kafka; everything is psycholog[ical] instead of having good strong men who fight well. But for me, the Westerns made America romantic. And I saw magazines from America with pictures of cars and houses.14

His wife jokingly suspected a slightly different motivation: ‘Two things attracted him here… the cars and the women. But both were spectator sports for him. He saw the American show girl who went to Holland with platinum blond hair, skinny legs, and fantastic builds. It was an admiration for streamlined cars and streamlined legs’.15 De Kooning liked Frank Sinatra, Broadway shows, detective novels and comics even while enjoying the novels of William Faulkner and Fyodor Dostoyevsky and, later, the philosophical writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein.16 Across the decades, his women materialised out of this mélange of popular and intellectual culture.

Most of the women in his paintings from the 1960s, however, were born from the beaches of the east end of Long Island, far from the urban chaos of New York City, although Women Singing II references the popular culture of the city as seen through the singers and dancers on TV. Furthermore, while other paintings and drawings of women of the time depict leisurely beach scenes and individuals lolling in the sun, de Kooning’s concern with the relationship between figure, ground and environment remains constant throughout all of the paintings.

Fig.8

Willem de Kooning

Woman 1965

Oil on wood

2032 x 914 mm

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In the 1950s de Kooning painted his women in ambiguous spaces. It is difficult to know if they are inside or outside, on a porch or near the water. Whether the setting de Kooning depicted in Woman I (fig.5) is a room, as is suggested by the vaguely rectangular shape behind her head and what appears to be a wall or a doorjamb to the right, or is the water in Holland, as his friend and fellow Dutchman Joop Sanders suggested, remains unclear.17 Thomas Hess described this space, this ‘no-environment’, as anonymous and without scale, explaining that ‘the corner of a skyscraper could be a corner inside a stockbroker’s parlor’.18 Because of the anonymity and lack of scale, the spaces were malleable, interchangeable with one another, not unlike the way de Kooning described his handling of body parts. Later Hess argued that once de Kooning moved to the country in the early 1960s his depiction of space changed. The timelessness and commonplaceness of the landscape of Long Island created a natural – not man-made – ‘no-environment’. Hess claimed that de Kooning painted women on door panels shortly after his permanent relocation to Springs in East Hampton in 1963 because ‘he wanted the anatomy to fill the whole surface, because he had no background, or environment to fit in’ (see, for example, Woman, Sag Harbor 1964 and Woman 1965; figs.7 and 8).19 In drawings from the mid-1960s, de Kooning began to become more familiar and comfortable with the new environment and started placing the female figures in rowing boats or on the beach, but in his paintings, including Women Singing II, there is still little or no environment for the women and they reach to the compositions’ edges. One cannot lift the figure from the space de Kooning depicts, no matter where she is.

One can speculate, and many have, about why de Kooning continuously returned to the female figure, and its meaning for the artist. Scholars and critics point to his difficult relationships with his wife and with his mother; his serial womanising; his love of popular culture; and to the perceived plight of women in mid-century America.20 Whatever the personal or cultural reasons, for de Kooning the painted female figure was always a way to explore the process of form-making and paint handling. In grappling with the controversies of de Kooning’s women, art historian Linda Nochlin concludes that: ‘Far from being sexualised icons of feminine seductiveness on offer, like so many of Picasso’s images of Dora Maar … these are fierce and well-defended creatures, even their pneumatic bubble-gum pink breasts suggesting a kind of armor against potential aggression.’ She goes on to observe of de Kooning’s Woman and Bicycle 1952–3 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York) in particular that ‘What is seductive … is the paint surface itself’.21 As much as de Kooning did make a painting of singing/screaming women, he also made a painting about painting by allowing the nature of the paint and the image-making process to remain visible on the surface of the paper.