Fig.1

Willem de Kooning

The Visit 1966–7

Oil on canvas

1524 x 1219 mm

Tate T01108

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

After years of cajoling, in 1966 Willem de Kooning agreed to a retrospective of his work. He had resisted for many years, telling one reporter, ‘They treat an artist like a sausage, tie him up at both ends, and stamp on the center “Museum of Modern Art”, as if you’re dead and they own you’.1 De Kooning’s vivid description exposes a fear and anxiety about the canonisation of artists and art world practices. An artist’s work, and his or her own person, is fed through the curatorial apparatus, homogenised, neatly tied up and fixed at either end, and encased in critical and institutional rhetoric, only to then be disposed of and sold. De Kooning’s fears were not completely unfounded. His retrospective, organised by critic Thomas Hess, opened at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1968 with much fanfare, not least because de Kooning returned to his native country for the first time in forty-two years to attend the opening. The show then travelled to the Tate Gallery in London at the end of the year and to New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1969.2 The reviews of the London leg of the exhibition were not all bad but mostly tepid.3 While some critics praised the exhibition and the early work in particular, there were also many accusations of decadence and irrelevance in regard to the new work of the 1960s. Critic Andrew Forge was perhaps the most prescient of the English critics in describing not only the critical reaction but also the underlying nature of de Kooning’s newest offerings. After seeing the retrospective several times, Forge observed, ‘A room full of the most recent figures can induce real genital panic’.4 With the material sensuousness and frank depictions of sexuality of paintings like Women Singing I 1966 (private collection), The Visit 1966–7 (fig.1) and Woman, Sag Harbor 1964 (fig.2) (Women Singing II 1966, Tate T01178, was not included in the retrospective), one senses that Forge neatly summed up the effect of de Kooning’s retrospective on critics who saw these new paintings as self-indulgent and vulgar.

Fig.2

Willem de Kooning

Woman, Sag Harbor 1964

Oil and charcoal on wood

2032 x 914 mm

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

It will be suggested here that, genital panic aside for the moment (although this is important too), the critics were not able to comprehend the recent work because they failed to grasp the full implications of the earlier work, despite their praise of it. De Kooning’s insistence on materiality, on a felt sense of space, on being grounded in the world and history (in a physical sense) informed much of his painting from the 1940s onwards. I would argue that this embodiedness in myriad ways also informed the paintings made by his abstract expressionist colleagues and friends. In fact, the body – variously in its representation, suggestion and absence – is central to abstract expressionism. This bodily aspect of abstract expressionism should have been ripe for consideration in the later 1960s with a newfound criticism shaped by phenomenological theory and scores of artists exploring the body, but the movement had already suffered the effects of sausage-making – had been stamped and sold. Critics and collectors quickly established the narrative of abstract expressionism in ways that excluded this phenomenological approach to its interpretation.5 Paintings such as Women Singing II and de Kooning’s reception in the 1960s offer us a chance to rethink the implications of abstract expressionist painting and its relation to the body.

Fig.3

Willem de Kooning

Excavation 1950

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Most reviewers in England recognised de Kooning’s status as one of the great American painters, along with the deceased Jackson Pollock, and even as an old master, like Titian or Rubens. The general consensus was that his ‘abstract expressionist phase’, meaning the works of the late 1940s and early 1950s like Attic 1949 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and Excavation 1950 (fig.3), was by far the strongest, but by most accounts the more recent work of the 1960s was seen to have floundered. The art critic for the glossy magazine Queen praised the earlier work but wrote,

Around 1960, though, something starts going soft, the dynamism threshes and wobbles. The most recent paintings, up to 1967, are Dionysiac orgies of flesh-painting, but like the whole second half of the exhibition, they seem lush and self-indulgent rather than strong. And they get further and further away from the tautness and precision which most painting of the Sixties has searched for, precisely because Abstract Expressionism had started going too far in the other direction. And de Kooning no longer looks relevant.6

Perhaps the critic had in mind the increasingly spare abstractions of Ben Nicholson or the op art of Bridget Riley, or even the colour field painting of Kenneth Noland. Compared to these ‘cooler’, more precise artists, de Kooning’s paintings like Woman, Sag Harbor, The Visit and even Women Singing II are lush and fleshy. With this criticism, a dichotomy between earlier paintings – strong, dynamic, hard – and newer paintings – wobbly, uncoordinated, soft – sets the stage for the newer paintings’ dismissal.

Critic Norbert Lynton, writing for the Guardian, assessed the difference between the ‘classic’ de Kooning and the ‘new’ de Kooning by writing, ‘Now he has to fight his own innate charm. I see the work that follows as a battle between the coonskin ideal that de Kooning set himself and his very sweet aesthetic tooth. And in his work of the 1960s the battle seems to be decided in favour of sweetness’. Lynton continued:

In his latest works he is painting jolly pink girls, with genitals and buttocks now as well as breasts and man-eating faces, and the fury seems to have changed into decorative playfulness. But ‘when I seen a man of my own age with a bright scarf around his neck speeding by in one of those low-slung cars – I want to kill him!’.7

Here Lynton used de Kooning’s own quote from the exhibition catalogue against him to suggest that no one enjoyed seeing a man of de Kooning’s age, now 64, produce what Lynton considered over-the-top pictures. The English critics, while admiring of the earlier work, expressed a deep unease with the new. There was no doubt that the painterliness of these works evoked flesh in a way that the gesturalness of the 1950s did not, and for these critics the colour palette of pinks, peaches and creamy yellows slathered on the canvas seemed not only inappropriate for a man in his mid-60s but out of step with the art of the times. With the rise of minimalist sculpture, hard edge painting, performance art and conceptual art, critics could not place the paintings in contemporary discourse or take them as serious contributions.

The more cynical consensus was that de Kooning had somehow sold out with these newer paintings, and thus they were easier to dismiss. In a radio broadcast discussing the exhibition, critic Edward Lucie-Smith explained that the works of the 1940s and 1950s were the most important ‘but then it all turns, kind of rich people’s – into a kind of boudoir art … the late pictures are almost insulting, you know, that they are too hedonistic, they are too… too much the sort of thing to hang in a pretty New York drawing room’. Later in the discussion the unnamed chair of the broadcast agreed, ‘I think we’ve given a feeling that this man is cashing in on what he knows will sell in some way’.8 For some critics, the paintings were not only vulgar from an aesthetic point of view but also spoke to the vulgarity of the collectors who would hang them in ‘boudoirs’ or flaunt them in their drawing rooms.9

With these assessments – that the paintings were too sweet, too lush, too playful, too driven by the market – came the perception that the works of the 1960s were somehow ‘easier’ than the paintings that came before them. Yet while the colours and forms changed over the decades for various reasons, de Kooning still struggled with image making. In a letter to Edy de Wilde, the director of the Stedelijk Museum, written during the summer of 1966 just after he had agreed to the retrospective, de Kooning admitted, ‘I have always had an anxiousness about the days passing. More even lately so … Also,..I could not yet send you one of my very good paintings so far,….while I am working continuously every day……in spite of… (or because of it for that matter) I am not really satisfied with the work’.10 In another letter from later that year, he wrote to collector and patron Joseph Hirshhorn, ‘Over here, …things are peacefull…ordinaire..and for me exciting…for months now am working on the same painting…it’s exciting..yes….but in another way miserable’.11 De Kooning never specified which painting or paintings he was working on, but he could easily have been referring to The Visit and the numerous works it spawned, including Women Singing II. While he might not work on a canvas for two years, as he did in the early 1950s with Woman I 1950–2 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), de Kooning would spend months with a single canvas, painting an image, scrutinising it, tracing it onto vellum, transferring it onto newspaper, scraping it down and starting on it anew the next day – all as part of an ordinary day’s work, which, as de Kooning describes, was both thrilling and terrible.

When De Kooning’s good friend Herman Cherry wrote to another old friend, the sculptor Reuben Kadish, towards the end of June 1966, he recounted, ‘I had a long art talk with Bill this morning. He is having a struggle with his paintings lately. It is a personal artist struggle, like an old time artist. He laughs about it, it all seems so silly’.12 There is a recognition or self-awareness here on de Kooning’s part that such personal struggle, explained in terms of existentialism during the 1950s, had become clichéd and seemed misplaced in the 1960s, even if it still seemed to gird the critics’ more serious estimation of de Kooning’s earlier work.13 ‘Silly’ is almost certainly de Kooning’s word and not just Cherry’s gloss, but it is likely that de Kooning would have felt that his struggle in previous decades was also ‘silly’. After all, we are talking only about ‘so many spots of paint or brushstrokes’.14 But this silliness made the struggle no less real. No matter if the painting might look ‘dynamic’ and ‘strong’ or ‘jolly’ and ‘sweet’ according to the critics, the anxiety of image making that plagued de Kooning while he painted Woman I in the early 1950s was still very much with him in the 1960s.

Lynton’s assessment that de Kooning betrayed his ‘coonskin’ ideal with these sweet, fleshy women born from popular culture was a common one, but it also underscores what the critics missed in de Kooning’s work of the 1960s. Lynton misunderstood coonskinism, or at least missed critic Harold Rosenberg’s point in the 1954 essay ‘Parable of American Painting’ in which he defined the term. Coonskinism meant to be unconcerned with style or maintaining consistency; it ‘is the search for the principle that applies, even if it applies only once. For it, each situation has its own exclusive key’.15 The coonskin artist does not turn to previous styles but to current styles outside of art and to specific problems. The paintings of earlier American artists such as Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) and Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917), even as different as they were in their tendencies toward realism and romanticism, participated in the ‘non-look’ of coonskinism. According to Rosenberg, they did not rely on previous examples, and their attempts to grapple with ‘Truth and Beauty’ were ‘the result of a specific encounter’.16 Similarly, de Kooning’s paintings are always about the specificity of an encounter with the world, with his environment, at a particular time. Lynton gets coonskinism precisely wrong: the fact that de Kooning did not continue to paint canvases that looked like Attic or Excavation and turned to what he saw on the local beaches, in magazines and on nightly TV is a testament to his coonskinism. De Kooning always took from his environment, even at his most abstract, and the women of the 1960s make his borrowing even more abundantly clear.

The abstract expressionist sausage

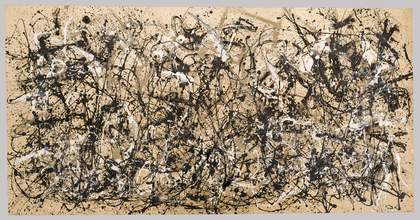

Fig.4

Jackson Pollock

Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) 1950

Enamel on canvas

2667 x 5258 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation, Inc.

Fig.5

Mark Rothko

Untitled c.1950–2

Oil on canvas

1900 x 1011 mm

Tate T04148

© Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko/DACS 2017

Just as the art world had packed and stamped the Willem de Kooning sausage, by the time of de Kooning’s retrospective in 1968 it had also made sausage out of abstract expressionism as a whole. De Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, Clyfford Still, Franz Kline and Adolph Gottlieb were its main practitioners. Already in 1965 when the Los Angeles County Museum of Art presented New York School: The First Generation, 15 Artists, a frustrated Newman felt that ‘the attitude toward the show by those who organised it [was] as if we were all dead’ and that ‘the doctors of art history are not so much doctoring history as they are hoping that the patient will disappear’.17 Abstract expressionist painting was large-scale, abstract, all-over painting, Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) 1950 (fig.4) and Rothko’s Untitled c.1950–2 (fig.5) being emblematic. De Kooning’s women paintings and Pollock’s later, poured black paintings that tended toward figuration were, purportedly, aberrations (see, for instance, Pollock’s Yellow Islands 1952, Tate T00436), or rather many felt that the so-called ‘return’ to the figure was a betrayal of avant-garde practice. In 1962 art critic Clement Greenberg declared that the painterliness of Still, Rothko and Newman’s work was the way forward for contemporary painting, and that the so-called ‘homeless representations’ by de Kooning, Kline and Philip Guston were all but a dead end. In Greenberg’s estimation, ‘homeless representation’ came about in the 1950s because the artists wanted ‘a more coherent illusion of three-dimensional space’ and so turned to a ‘tangible representation of three-dimensional objects’, and de Kooning’s women paintings of the 1950s were regarded as prime examples. Of course, the work of Kline and Guston was not so overtly representational at the time, but their abstractions lent themselves to interpretations of the figure, as was the case with Guston’s The Return 1956–8 (fig.6), with its suggestion of a group of people seen from behind, and Kline’s Meryon 1960–1 (fig.7), evocative of a clocktower. While Greenberg did not completely condemn ‘homeless representation’ outright, he felt that it too easily devolved into a stylistic device readily exploited by artists.18

The standard view of the relationship between the body and abstract expressionism focuses on the performative aspect of the artist’s painting process – as evidenced by the countless references to Hans Namuth’s photographs of Pollock painting taken in 1950 – and neglects important ideas about the body expressed by the artists themselves and by contemporary intellectuals. With representation banished, abstract expressionism’s all-over, abstract surfaces became, in the critics’ and art historians’ estimations, not only the epitome of abstract expressionist style but also the foil for Robert Rauschenberg’s combines, Jasper Johns’ flags and targets, and the pop art that embraced popular culture (see, for instance, Rauschenberg’s Rebus 1955 and Johns’s Map 1961, both Museum of Modern Art, New York). Younger artists, critics, curators and collectors ‘knew’ what abstract expressionism was. With the canon in place, and with the fixed narrative of the artists’ origins and commitments, it was now easy to dismiss them as irrelevant in the mid-1960s. Minimalist sculptor Donald Judd’s 1964 assessment was a common refrain. Judd wrote, ‘There is a vague, pervasive assumption … that Abstract Expressionism is dead, that nothing new is to be expected from its original practitioners and that nothing new will be developed from it, nothing that would be identifiable as deriving from it and that would also be new. It sure looks dead’.19 Judd did suggest that one could imagine de Kooning painting great pictures again, but that his 1966 paintings were not these.20

Greenberg’s suspicion of representation had to do with narrative and its unwelcome place in painting; narrative belonged to literature, not painting. But Greenberg’s insistence on optical experience – that is, an objective, distanced, disembodied viewing – forced the viewer to imagine him- or herself from a distance and not necessarily as a body, looking.21 Thus, by diminishing representation and the figure in abstract expressionism and abstracting the viewing experience, critics and historians have overlooked the importance of the body – its representation, its suggestion, its absence – in abstract expressionist painting. Even when bodies are not represented on the surface of the painting, as they are in so many of de Kooning’s paintings, the bodies of the artist and the viewer are central to an understanding of abstract expressionist painting.

The phenomenological turn

Even with the serious and important revisions historians have made to the story of abstract expressionism, such discussions have neglected the body and allowed the calcified, canonised representation of abstract expressionism to guide interpretations of what happened to art in the 1960s. There has been the tendency to overlook the ways in which abstract expressionism presaged what art historian Alex Potts has termed ‘the phenomenological turn’ of the 1960s.22 Citing the numerous translations of the writings of French philosopher and phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty that were available beginning in 1960, the year before his death, and examining how the philosopher was taken up by critics such as Rosalind Krauss and Michael Fried in their early writings on sculpture in the 1960s, Potts uses this turn to discuss the state of sculpture in the 1960s as practiced by Judd, Carl Andre, Robert Morris and others. But Merleau-Ponty and other phenomenologically oriented philosophers such as Martin Heidegger were known among the abstract expressionists’ interlocutors, including Harold Rosenberg, the art historian Meyer Schapiro and the philosopher William Barrett. Just as Potts uses Merleau-Ponty’s ideas to reconsider sculpture in the wake of an anti-formalism that privileged language over vision, considering de Kooning and abstract expressionism in terms of phenomenological effects resuscitates a movement at a time when it was thought dead.

As Potts describes, Merleau-Ponty ‘offered a new way of thinking within the physical environment’.23 While Greenberg may have advocated for a disembodied eye, the abstract expressionist painters held no such illusion that a disembodied eye could exist, as can be seen in their careful attention to the way in which they hung their paintings. When Rothko installed his canvases at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York in 1956, he placed them close to the floor and sometimes even abutting the doorjambs. There was little chance of viewing the paintings from a distance, and the viewer could not help but have a bodily interaction with them. By arranging the paintings in this manner, Rothko brought to the fore the physicality of looking. The viewer is made aware of his or her bodily presence in experiencing – in looking at – Rothko’s paintings.

As described elsewhere in this In Focus, de Kooning’s pictorial space was not merely illusionistic but involved a felt sense of his own body inhabiting a particular space.24 Potts’s gloss on Merleau-Ponty is helpful here. As Potts explains, ‘The body image Merleau-Ponty talks about … is the internalised sense we have of our own body as we apprehend things in the world around us’.25 In describing the Renaissance artist, de Kooning explained to his colleagues that perspective was not just a neat trick and that the goal of the artist was to be ‘on the inside of his picture’. De Kooning emphasised that measuring space was more about subjective feeling than mathematics.26

Fig.8

Willem de Kooning

Attic 1949

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

One can consider Attic from 1949 (fig.8) in light of de Kooning’s talk. De Kooning provides himself and the viewer with a bit of wood-planked floor on which to stand amid the cloth-draped furniture and forgotten things. The canvas itself is only about 1.5 metres tall and 2 metres wide – not so big as to overwhelm the viewer or the artist. One imagines de Kooning pushing and arranging the shapes around the canvas – shapes that never quite coalesce into recognisable objects but which still feel weighty and hefty.

As Potts explains, already by the end of the 1960s phenomenology had fallen out of favour, as ‘any privileging of a visual, or even physical dimension to responses of art works’ was deemed suspicious. He continues, ‘Insomuch as modernist formalism was updated, it was not by giving it a phenomenological grounding in the bodily dimensions of viewing, as Fried and early on Krauss sought to do, but by thinking of formal structures as echoing certain underlying patterns of articulation that governed linguistic sign systems’.27 Even if phenomenology informed critics’ discussions of sculpture, they did not employ it in their discussions of painting.28 That is, at a moment when critics and art historians were better equipped to recognise the phenomenological turn that the abstract expressionists had accomplished, they had moved on.

Fig.9

Willem de Kooning

Women Singing II 1966

Oil on paper on canvas

914 x 610 mm

Tate T01178

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Not everyone moved on though. In a curious and rarely noticed moment in 1964, the young critic Susan Sontag used part of de Kooning’s 1960 interview with David Sylvester as one of the epigraphs to her important essay ‘Against Interpretation’, in which she called for an erotics of art.29 She never addressed de Kooning or his art specifically in the essay, but his statement, ‘Content is a glimpse of something, an encounter like a flash. It’s very tiny – very tiny, content’, is the first thing one reads at the beginning of her essay.30 For Sontag, our inclination to interpret art – that is, to assign meaning – has led us astray in that we no longer experience art. We have overemphasised content to our – and art’s – detriment. She wrote, ‘By reducing the work of art to its content and then interpreting that one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable, conformable’.31 De Kooning’s insistence that content is tiny, that there’s not much there to hold on to, to analyse or interpret, supports Sontag’s argument well in that it gives the sense that content is practically negligible, thereby forcing the viewer to focus on the art itself – that is, its physical nature. In his 1950 talk ‘The Renaissance and Order’, de Kooning had described the state of painting during the Renaissance, writing, ‘[T]here was no “subject matter”. What we call subject matter was the painting itself. Subject matter came later on when parts of those works were taken out arbitrarily, when a man for no reason is sitting, standing, or lying down’.32 For de Kooning, the subject matter of painting is the painting, which is the subjective space measured by the artist’s own body. Of course, de Kooning does not do away with content and in fact is able to accomplish much with it, however ‘tiny’. Art critic John Perreault, like Andrew Forge, was one of the few critics at the time who understood what de Kooning was doing in his paintings of the 1960s. Perreault was pleasantly surprised when he saw de Kooning’s new paintings at Knoedler’s in New York in 1967, an exhibition that included Women Singing II (fig.9). In speaking generally of artists who used the figure as a compositional device, Perreault observed that ‘In de Kooning’s case it is the female figure as “felt” and experienced subjectively rather than seen point blank’.33 One can go back to de Kooning’s ideas of intimate proportions or his own bodily space to understand that de Kooning put sensing, and not interpreting, at the forefront of his work.

Recovering the senses

Sontag concluded her essay by writing that ‘Interpretation takes the sensory experience of the work of art for granted, and proceeds from there’. She continued, ‘What is important now is to recover our sense. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more … Our task is to cut content back so that we can see the thing at all … In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art’.34 De Kooning did not do away with content or make it unimportant as much as he asserted that something small or mundane is worthy of being content. But to Sontag’s main point, de Kooning did strive to see and feel more, which is why he always emphasised the materiality of the surface of the painting. It is not just that de Kooning was painting sexually explicit, erotic images of women, but also that the surfaces of his paintings ‘feel’ a certain way. The application of paint makes one consider the painting itself. The surface of Women Singing II is slick and creamy. One can feel the twisting of the figures because of the slickness of the paint and the way they feel in their shallow space.

Forge was the first to capture the implications of Sontag’s call for an erotics of art and its relation to de Kooning. In describing the chaotic, though structured, surfaces of de Kooning’s canvases, Forge wrote,

This mess – it is a way of describing both the facture and the structure, for they can hardly be separated – this mess is body like. It is sensate, nervous, alive … Of course, it could be said that whatever we look at contemplatively, whether in the real world or in art, we absorb into ourself, assimilate to our bodies. Even the most distant view or the most rebarbative form becomes a metaphor for something or some state within us once we work on it esthetically … With [de Kooning], looking seems a total physical commitment. The dialectic of looking is put to work on the deep tablet of a canvas that is itself a surrogate for the body; and there through the painting experience, there are reconciled extremes of fragmentation and wholeness, violence and repose.35

It is not just that the painting becomes a surrogate for the body in Forge’s interpretation. It is that looking is a ‘physical commitment’. In the misreading of Harold Rosenberg’s idea of action painting, we assume a frenzied, physical making, but by many accounts de Kooning probably spent more time looking at his paintings than putting marks on the canvas. Again, Potts’s description of Merleau-Ponty is helpful. In the philosopher’s estimation, ‘A drawing or painting is no longer simply envisaged at this point as a frozen trace that functions to make the artist’s process of perceiving immediately manifest to the eye of the viewer. It is rather something which draws the viewer into an intensified awareness of how he or she sees things’.36

Fig.10

Willem de Kooning

Woman on a Sign I 1967

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Women Singing II might not be de Kooning’s most erotic painting – it is not the splayed-legged women of The Visit or Woman on a Sign I 1967 (figs.1 and 10) – but curator Lynne Cooke has written eloquently of what the erotic meant in the 1960s for Sontag and other thinkers such as Herbert Marcuse and Norman O. Brown and its relation to de Kooning’s paintings from the time: ‘The erotic is manifest in the absorption and dissolution of one body into another, and, with this surrender of the ego, into pure sensation. This invitation to loss of self in an undifferentiated sensual matrix is in turn extended by submerging the figure into its context and by blurring its boundaries with the ambience’.37 Women Singing II can be a metaphor for this absorption in that the figures begin to meld with the background, but also, taking a step back from its content, its subject matter in the traditional sense of the term, it asks us to consider how we see this physical painting – how we take it into ourselves, as Forge suggested.

De Kooning, however, was not one to lose himself in such absorption. Going back to ‘The Renaissance and Order’, de Kooning explained that Renaissance artists ‘never became the thing himself, as is usually said since Freud. If he wanted to, he could become one or two sometimes, but he was the one that made the decision. As long as he kept the original idea in mind, he could both invent the phenomena and inspect them critically at the same time’.38 De Kooning’s pragmatism kept him grounded in the world in the present, not floating in the ‘undifferentiated sensual matrix’. The artist and the viewer remain critical, aware of their body in relation to the body of the painting. Sontag’s call for a return to the senses and Merleau-Ponty’s embodied vision facilitate a new reading of abstract expressionism that calls us to consider a painting as a three-dimensional object hanging on the wall in front of our own body, in our own space. And de Kooning’s canvases remind us that looking is physical, is felt: that we as physical beings are part of the depth of the world.