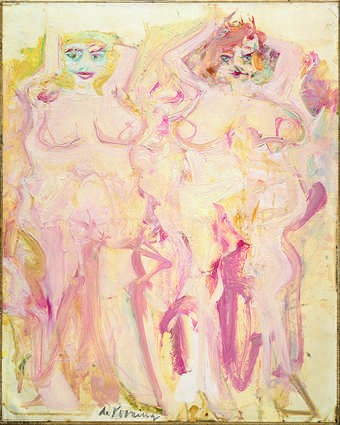

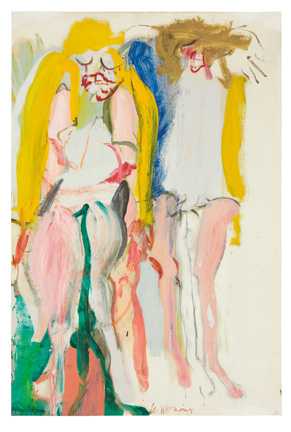

Fig.1

Willem de Kooning

Women Singing II 1966

Oil on paper on canvas

914 x 610 mm

Tate T01178

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The image-making process remains very visible on the surface of Women Singing II 1966 (Tate T01178; fig.1), in the sense that one can imagine how and when Willem de Kooning placed brushstrokes onto the paper. There is, however, a caveat to this visibility. This singular work on paper reveals only part of de Kooning’s creative process. The full development of this work must be tracked over at least seven other paintings and drawings made during the course of 1966, two of which are the closely related Singing Women 1966 (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam) and Women Singing I 1966 (private collection). The interrelations between these and other works of art are numerous and tangled. It is nearly impossible to create a definitive timeline of the order in which the works were completed, as de Kooning would come back to a painting on numerous occasions over a period of time, but one can imagine a probable narrative. De Kooning was notorious for working on a single painting for months, even years, as in the case of Woman I 1950–2 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), a painting that generated countless other drawings and paintings – sometimes on the same canvas – as he worked through particular artistic problems between 1950 and 1952. De Kooning’s approach to his creative process was not entirely different in 1966.

Drawing, tracing and collage

Fig.2

Willem de Kooning

Collage 1950

Collection of Mr and Mrs David M. Solinger

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Although de Kooning’s process changed over the years, with new studios and different materials, he was fairly consistent in using various techniques of drawing and tracing to work through his painting compositions. In the late 1940s and into the 1950s he would often use a collage method to figure out his compositions of interlocking shapes, tracing the forms onto paper and arranging them in various ways across a painting’s surface.1 In Collage 1950 (fig.2), de Kooning did not remove these painted pieces of paper and even kept in the finished composition the steel tacks he had used temporarily to hold the pieces in place. Even if many of the paintings from the 1940s and 1950s do not remain physical collages, their compositions of overlapping shapes and combinations of scale recall the collage process.

Throughout his career de Kooning would often begin a work with drawings. These drawings would litter the floor and be picked up and used again as he worked through a composition, sometimes becoming collage material or acting as jumping off points for new compositions that he would trace onto other pieces of paper or canvas. This tracing would continue into the 1960s when he started using large sheets of vellum – a heavy, translucent paper – to trace whole figures or their parts. De Kooning would sometimes transfer these images to canvases to begin new paintings, or the vellums would become paintings themselves.2 During this period he would also apply newspaper to the wet surface of paintings in progress and then pull the newspaper away, thus creating something like a monoprint on the newspaper, which he could transfer to another canvas or leave as a work in and of itself.

Fig.3

Willem de Kooning

The Visit 1966–7

Oil on canvas

1524 x 1219 mm

Tate T01108

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.4

Willem de Kooning

State photograph of The Visit 1966–7 taken by John McMahon

Courtesy of The Willem de Kooning Foundation

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

It is likely that Women Singing II involved some of these processes at various stages. The evolution of Women Singing II begins with another painting in the Tate collection, The Visit 1966–7 (fig.3). The Visit, by many standards, is a difficult painting. Using thick and thin strokes, de Kooning depicts a female figure with her legs spread almost as if she is squatting, a pose that was not uncommon in his work during the 1960s. She seems inseparable from her background, her body barely contained by its rough contours.3 Her face is not the sweet smiling one that the viewer finds in so many of his canvases from the 1960s but instead is a little frog-eyed, rendered in greenish-brown paint that lends her face a mask-like quality. Another mask-like face seen in profile floats in the upper right corner; their relationship is difficult to discern. Like countless others of de Kooning’s canvases, this one was built up, scraped down and built up again over a period of several months. During its creation John McMahon, de Kooning’s studio assistant at the time, took photographs of the canvas when he arrived in the mornings ‘if the picture looked interesting’.4 Close examination of these photographs would be an essay in and of itself, but as will be shown, one of the first stages of the painting (fig.4) reveals a direct connection to what would become Women Singing II.

When beginning a new work, de Kooning would often refer to existing images that were easily at hand in his studio. Although his studios changed over the years, de Kooning’s methods were fairly constant. Thomas Hess, the art critic and friend of de Kooning, described the artist’s studio process in 1959:

Drawings remain in the image as shapes painted where drawings had been taped to the canvas, and in edges and transitions, long after they have been discarded. Once they have left the picture they remain in the studio, becoming part of the ‘no-environment’, scattering around the ship-shape floor like crazy lilypads on a hardwood pond. Later they will be neatly stacked away in portfolios, as well-thumbed as favorite books. And as such they may re-enter the paintings again, tacked to the wall behind Woman; torn and cut apart again they suggest new departures, but the departures keep the hereditary intonation of the parent drawings.5

While Hess spoke mostly of drawings, canvases were equally at the ready to provide de Kooning with jumping off points.

Fig.5

Willem de Kooning

Marsh Landscape 1966

Oil on canvas

762 x 635 mm

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.6

Willem de Kooning

Color for Blonde Woman 1966

Oil on canvas

762 x 635 mm

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Researchers at The Willem de Kooning Foundation have determined that parts of the first state of The Visit resemble two other paintings that de Kooning created in 1966. The bottom left contains the image of the top half of Marsh Landscape (fig.5) and the bottom right quadrant contains Color for Blonde Woman (fig.6).6 Even with what we know of de Kooning’s working methods and the current photographic evidence, how de Kooning began the canvas that would become The Visit remains a mystery. Whether the images on the small canvases Marsh Landscape and Color for Blonde Woman intrigued him enough to transfer to the large canvas, or whether he began the images on the larger canvas and wanted to preserve them to develop them later, is unknowable without careful examination of the physical canvases in question. What can be said is that even though de Kooning quickly painted over the image related to Color for Blonde Woman in subsequent states of The Visit, this particular image held de Kooning’s attention and imagination for some time and eventually culminated in Women Singing II.

Color for Blonde Woman and its inheritors

Fig.7

Willem de Kooning

Clamdiggers 1963

Oil on paper on composition board

514 x 368 mm

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.8

Willem de Kooning

Two Standing Women 1963–4

Oil and charcoal on paper mounted on canvas

740 x 591 mm

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

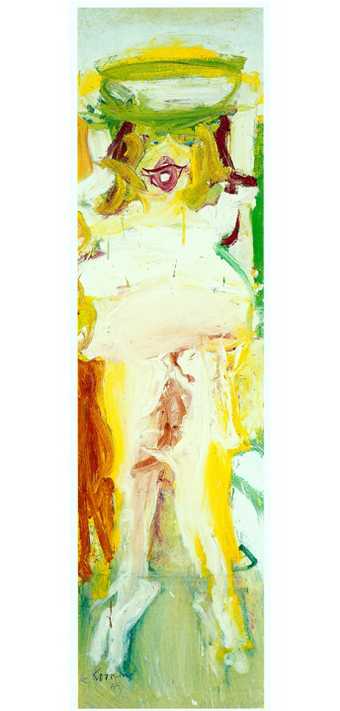

When de Kooning moved permanently from New York City to Springs in East Hampton in 1963, larger-scaled female figures began to occupy more of his paintings than they had in the previous years, when he worked on large abstract landscapes such as Door to the River 1960 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York) and Rosy-Fingered Dawn at Louse Point 1963 (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam).7 Small works on paper such as Clamdiggers 1963 (fig.7) and Two Standing Women 1963–4 (fig.8) depict light, voluptuous nudes in various poses. When he began to work in the new studio that he was building (construction was ongoing for several years), he continued to paint female figures, some on doors that were purchased but not used for the studio, with Woman, Sag Harbor 1964 (Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.), Woman 1965 (fig.9) and Singing Woman 1965 (fig.10) being representative. Placed among these contemporaneous works, Color for Blonde Woman feels different, as if de Kooning was in pursuit of something other than capturing light playing off of flesh or the relationship between figure and ground.

Fig.9

Willem de Kooning

Woman 1965

Oil on wood

2032 x 914 mm

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.10

Willem de Kooning

Singing Woman 1965

Oil on paper mounted on canvas

2235 x 610 mm

John and Kimiko Powers Collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The title indicates a singular – woman – but there appear to be two figures, although I use the word ‘figure’ here reluctantly. These are not the voluptuous, erotic female forms from his recent paintings; in fact, they are barely figures at all, having no facial features, no arms and no legs. Yet the peach colour and the orientation suggests two women with long blonde hair seen in profile, facing each other. It is possible that the brown strokes between them suggest the torso of a singular figure, and if one looks closely at the first state of The Visit (fig.4), the two figures are not as apparent as they are on the smaller canvas. After the transfer to or from The Visit canvas, de Kooning made the delineation between the figures on the smaller canvas more decisive by bringing the yellow paint down to a point between the two peach-coloured swathes and emphasising the edges of the peach colour.

One senses, however, that the figures themselves were of little importance, and that the hair and its colour captivated de Kooning more. He was particular about his painting colours, creating recipes for very specific colours that he came across in his daily life. As Hess explained,

De Kooning’s palette is organized in about eighty porcelain jars of colors he has pre-mixed himself, each with its special recipe, using regular commercial oil paints as ingredients. He started working out this system from a dissatisfaction with the available tube earth-pigments, which dry unevenly and leave a different finish from the mineral paints. With a few hints from the late Landes Lewitin, he decided to make earth colors out of mixtures of mineral ones, and, once he had established several basic hues, began to ‘breed’ them with each other, ending up with an enormous family of hues. Some are strange off-colors (‘This one is just like boiled liver’, he said of an innocent-looking brownish-gray); others are keyed up to the maximum intensity for oil paints.8

It is this yellow hair that de Kooning manipulated and changed for Singing Women, Women Singing I and Women Singing II.

The central motif of Color for Blonde Woman – two blonde waves surrounding two swathes of light peach paint – creates the central figure in Singing Women (fig.11). Given the nature of the surface of Singing Women, it does not appear to be a direct transfer of Color for Blonde Woman; de Kooning likely copied the motif in yellow paint onto the paper free-handed. The two figures from Color for Blonde Woman are now (again, perhaps) a single figure. A large open mouth with teeth and a single half-moon of an eye make a face between the blonde curves. The light peach strokes on either side become indistinct, fleshy arms instead of two separate bodies. From a smear of blue emerge long, slender legs with red, very high heels. To the right of this figure is a second indistinct form, outlined in blue; the face and hair are a swirl of orange paint with only the suggestion of high heels below. Perhaps in an effort not to lose the image of the main figure while working on the second, de Kooning used charcoal to trace the top half of the figure carefully onto a sheet of vellum and the bottom half of both figures onto another sheet (figs.12 and 13).

Fig.11

Willem de Kooning

Singing Women 1966

Oil on paper on masonite

914 x 610 mm

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

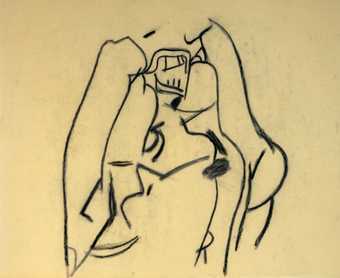

Fig.12

Willem de Kooning

Untitled c.1966–7

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

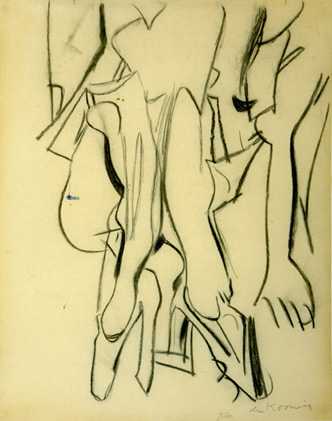

Fig.13

Willem de Kooning

Untitled c.1966–7

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

As already described, de Kooning would often use these tracings to start other canvases, sometimes tracing over the lines seen through the vellum onto a canvas or a piece of paper, creating a reversed image. Alternatively, he would trace the image seen through the back of the vellum and then trace that reversed image onto the canvas, recreating the figure in its original orientation. There is little evidence that de Kooning used the two tracings on vellum in either of these ways to create Women Singing I (fig.14) (although it is possible that he used them for another work). The mouth of the left figure in Women Singing I appears to be the reversed image of the mouth traced on the vellum, but it is looser, perhaps not strictly traced; neither do there appear to be any obvious passages of charcoal in Women Singing I that suggest that a transfer occurred. Not content to work linearly from one painting to the next, de Kooning went back to the form of Color for Blonde Woman for that of Women Singing I. The hook-shaped element on the left of the former reappears on the left of the figure in Women Singing I. Now the two swathes of yellow are joined at the top with more yellow, connecting the two long locks of hair. The yellow creates an ‘M’ shape within the figure, as it does in Color for Blonde Woman, which is then echoed across the composition with the addition of another stroke of yellow to the right of the second figure.

Fig.14

Willem de Kooning

Women Singing I 1966

Oil on paper on board

914 x 609 mm

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In Women Singing I the second, right-hand figure is more developed than in Singing Women. Her torso remains unpainted, but her legs are slender and pink, although shoeless. She too has a toothy, open mouth, but she sports a mess of brown hair on top of her head instead of long, blonde hair. In this composition the women have more space around them as compared to Women Singing II. They also seem more naked. In both Singing Women and Women Singing I one has the sense that de Kooning did not finish the compositions as one might typically, or traditionally, expect. Areas of the paper remain blank and each of the figures on the right is not as developed as her neighbour. De Kooning would often stop work on a composition because he thought it was interesting and liked it as it was, or because he had decided to continue and rework it on another surface. He told David Sylvester, ‘I always have a miserable time over that [finishing]. But it’s getting better now. I just stop.’9 For de Kooning, stopping did not have positive or negative connotations, and it was not as freighted as the word ‘finishing’. These two works, Women Singing I and Singing Women, did leave the studio signed not long after their completion, so their final states were not unfinished in the traditional sense, but rather were ‘stopped’ in de Kooning’s sense.10

When compared to Singing Women and Women Singing I, Women Singing II seems fuller, weightier, more twisted. The only indication that Women Singing II might have started with a transfer process is the left figure’s original mouth. It, too, seems to be the reverse of the mouth on the vellum, but again there is no visible hint of charcoal on the surface of the paper. De Kooning likely drew it freehand along with the rest of the composition. Although the left figure’s feet closely resemble the vellum showing the lower part of the composition, especially the figure’s left pointed shoe, de Kooning took liberties with most of the forms. The transfer process he developed and used throughout his career allowed him to keep and rework images that interested him, but he was never beholden to the image, changing it as he saw fit. As such, over six different surfaces, including paper, vellum and canvas, de Kooning worked and reworked these women – their anatomies, their colours, their relationships to each other and the background – as well as the way in which he handled the paint.

Memory transformed and embodied

De Kooning’s dealer Xavier Fourcade explained Women Singing II as ‘a memory of pop singers he saw on television’.11 De Kooning’s process, his openness and willingness to change, speaks to the very process of remembering, of creating a memory. When we talk about a memory we usually describe it rather simply: ‘I remember seeing pop singers on TV’. In his phenomenological study of remembering, philosopher Edward Casey reminds us that:

remembering transforms one kind of experience into another: in being remembered, an experience becomes a different kind of experience. It becomes ‘a memory’, with all that this entails, not merely of the consistent, the enduring, the reliable, but also the fragile, the errant, the confabulated. Each memory is unique; none is simple repetition or revival. The way that the past is relived in memory assures that it will be transfigured in subtle and significant ways.12

In many cases, we assume our memories are stable and accurate, but as Casey points out they are, in fact, ‘fragile … errant … [and] confabulated’. Memories can be complex and mutable, even one as innocuous as women singing on the television.

While Fourcade suggested that de Kooning remembered an image from TV, from what we know of de Kooning’s practice it is more likely a synthesis of remembered images, some of which were seen on TV, some perhaps seen in magazine advertisements or in Broadway performances. It was common for de Kooning to end the day in front of the television.13 In describing de Kooning’s drawings, Hess explained that sometimes de Kooning drew with his eyes closed and sometimes while looking at the television set, maybe drawing what he saw or just as easily something else entirely.14 In beginning the singing women paintings, perhaps he was remembering one performance or even one drawing he had already created; regardless, we see him changing the memory, moving between one and two figures and between blonde and brown hair. Even a single memory can be shifting and mutable.

When speaking to critic David Sylvester in March 1960 about why he painted the Woman series in the early 1950s, de Kooning famously explained, ‘Content is a glimpse of something, an encounter like a flash. It’s very tiny – very tiny, content’. He continued, ‘I still have it now from some fleeting thing – like when one passes something and it makes an impression’.15 Just a few months earlier, he explained the same idea in more mundane terms, ‘I see things I like. I don’t fight them. Maybe four or five months later they come back to me. I work by these associations … Even your shoe could hit me that way and I could make a painting. What you encounter is the most fantastic thing’.16 De Kooning’s paintings are born of mundane memories, memories of flashes and glimpses that one has when going about daily life. When one tries to go back to it in the studio, it changes; one can never quite get a hold of it, because it was just a glimpse, a flash. He explained to Sylvester:

Then I could sustain this thing all the time because it could change all the time … Because this content could take care of almost anything that could happen … I feel now if I think of it, it will come out in the painting. In other words, if I want to make the whole painting look like a puddle, like a lot of puddles, for instance – maybe the end of the day, when everything is very light, but not in sunlight necessarily – and so if I have this image of this puddle and if I really think about it, it will come out in the painting. That doesn’t mean that people notice a puddle, but I know when I succeed in it – then the painting would have this. They can interpret it their ways.17

De Kooning was not trying to represent his memories or paint a literal scene from television, but they informed his composition of Women Singing II from the beginning.

Casey argues that our understanding of memory has become externalised because of the technological analogies we use to describe it, ‘projected outside the rememberer himself or herself and into non-human machines’.18 One need only think of the references to computers, cameras and disk space when we discuss memory. Memory, however, was not external for de Kooning. De Kooning’s memory of the woman is not a snapshot; it is not a still frame of film. De Kooning physically created the memory in and with his body. Lisa de Kooning, the artist’s daughter, told his biographers that her father, when at the beach, would ask her, ‘“You see that?” and point to the miraculous and constantly shifting effects of light and color. And then, still staring at the water, he would raise his painting hand and, with his thumb and one finger, draw the line across the horizon, releasing his breath in a gentle “Sssssss…”’.19 This physical and audible gesture captured the moment that struck him – light hitting and gliding along the water. That gesture could then be remembered in the studio, paintbrush gliding along the canvas or paper. De Kooning’s memory of pop singers on TV is perhaps not as poetic as remembering the interplay of light, water and horizon, but it was an equally strongly felt memory for de Kooning. One can picture trying to mimic the bodily stance of the singers or stretching in such a way as to imagine what it feels like to hit the high note.

De Kooning’s memory was embodied memory. In a talk he prepared for a symposium at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1951, de Kooning wrote, ‘If I stretch my arms next to the rest of myself and wonder where my fingers are – that is all the space I need as a painter’.20 The space de Kooning projected onto the canvas was his personal space, the space he could remember and imagine his body occupying, rather than deep vistas of perspectival space. A year earlier de Kooning had explained to an audience of fellow artists at Studio 35 in New York how Renaissance painters developed perspectival space:

Perspective, then, to a competent painter, did not mean an illusionary trick. It wasn’t as if he were standing in front of his canvas and needed to imagine how deep the world could be. The world was already deep. As a matter of fact, it was depth which made it possible for the world to be there altogether. He wasn’t so abstract as to take the hypotenuse of a two-dimensional world … It was more intriguing to imagine himself busy on that floor of his – to be, so to speak on the inside of his picture. He took it for granted that he could only measure things subjectively … He shifted, pushed, and arranged things in accordance with the way he felt about them.21

At this point de Kooning was likely beginning, or about to begin, Excavation 1950 (Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago) and six months later he began work on Woman I, but this felt sense of space remained with de Kooning throughout his painting career. Even at his most abstract, de Kooning’s paintings were grounded in the world – his world, his glimpses of it and the memories he created. Women Singing II could very well be a memory of a scene on TV or the way an image was rendered on the TV screen, but it could also be a memory of mimicking the singers trying to hit the high note, a memory of Color for Blonde Woman and The Visit.