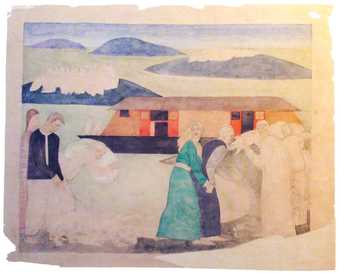

The British artist Winifred Knights painted The Deluge in 1920 (Tate T05532; fig.1). She produced it while studying at the Slade School of Art, London, as a competition entry for the prestigious Rome Prize for Decorative Painting, which was open to young art students in Britain and the Empire. The prize’s scholarship enabled its winners to spend time at the British School at Rome (BSR), to deepen and enhance their painting practice and to learn about Italian classical and Renaissance art, with a particular focus on mural painting. The Deluge depicts the biblical narrative in Genesis in which God punishes the sins of humankind by flooding the earth and saving pairs of animals and a single human family aboard Noah’s ark – a subject that was set by the Rome Prize organisers.

Fig.1

Winifred Knights

The Deluge 1920

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 1529 x 1835 mm

Frame: 1630 x 1930 x 55 mm

Tate T05532

© The estate of Winifred Knights

Photo © Tate

In the left of the painting, water cascades from the broken walls of a low-roofed tower with a single window. Below this two women stand ankle-deep in the rising waters, their hands pleading heavenward. Beyond them, a man looks back over his shoulder and a woman in a red dress – one of the two self-portraits in The Deluge – looks towards the pair of women with raised hands. In the centre of the painting is another woman, modelled on Knights’s mother Mabel, shown holding a young child, modelled on Knights’s baby brother David, who died in 1915. A man on the left in profile is based on Arnold Mason, a fellow artist and close friend to Knights throughout her short life.1 Further figures populate the centre and right of the composition, rushing towards the higher ground offered by a green slope on the right hand side. Among these are two figures who attempt to pull another from the water over to the brief safety of a small boundary wall. Further into the distance, figures cling to a hilltop protruding from the water’s surface, which Knights has rendered as no more than a slender shard. Buildings beyond, more factory-like than domestic, suggest submerged height as the water surges into them through windows and doorways.

In the centre-foreground the most dynamic figure of all – the other Knights self-portrait – outstretches her arms towards the green slope. Like the woman in the red dress, this figure looks back over her shoulder, this time gesturing forward with her two hands, her mouth open in a cry of uncannily reserved shock and her body taut with an ultimately futile strength. Her feet spread wide, one knee bends and the other leg remains straight with toes poised at a diagonal angle, touching the ground. The attitude of her body is entirely different to those beyond her in the right side of the picture, who appear to scramble up the hill desperately without a backward glance.

Perhaps the subtlest effect observable in The Deluge is the visual kinship between the submerged domestic architecture and the floating ark, a stark object which reminded one contemporary reviewer of ‘the concrete architecture we have now’.2 The ark is the painting’s most modern moment as well as its most mute and uncompromising strip of paint. Surrounding it, small green and brown patches register as both hills and islands, striking an anxious chord regarding the unstoppable torrent of water on the left side of the picture. Signs of agricultural order are rendered valueless by the onset of the flood.

Knights’s painting interpreted the biblical scene of Noah’s ark rising on the waters of a monumental and earth-transforming flood in a fresh and dramatic new way. The figures that flee from the waters, who try to help one another and attempt to protect their young children, will not be saved in Knights’s visual account of the Genesis narrative. None of them see the silent ark in the distance, its pale brown and gun-metal grey punctuated by a thin streak of red; more importantly, none appear to seek it. Knights’s figures display no knowledge of the source or the intentions of God’s actions. Their priority, displayed to the viewer with sharp, angular forms and a striking palette of metallic and earth tones, is impossible escape.

Knights painted The Deluge in a style that emerged from a range of influences, combining a cubist aesthetic with that of early Italian Renaissance frescoes and the emphasis on mural painting that held a special place at the Slade. The painting is distinctive for its limited palette, its attention to emotion, angular figures and solidly matte colour effects, particularly in the green-grey tones sparking off the vibrant passages of red. With its assertive expression of lessons learned from Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) as well as Piero della Francesca (c.1415/20–1492), The Deluge arguably helped to moved painting into a new position in Britain; it certainly set Knights’s relatively short artistic career in motion.3 Her fusion of historical knowledge in figurative and decorative art with a unique perspective on biblical themes characterises the small body of work she produced in the first half of the twentieth century.

This In Focus project argues from art historical and theological perspectives that Knights’s The Deluge is as much a visual explication of inexplicable suffering as it is a meditation on a specific theme given to Knights by the terms set out in the Rome Prize competition. In addition to her bold yet restricted palette of contrasting grey tones with zones of searing deep reds, Knights dressed the figures in the foreground in twentieth-century clothing. Using herself and those close to her as models, Knights also placed the action – the biblical flood narrative – in an ambiguous conjunction of no-place and every-place, of a biblical landscape of rising waters and a credibly modern social territory within which fear is evident on modern faces and pulses through modern bodies. This In Focus will therefore also examine the modernity of Knights’s representation in relation to contemporary themes and practices including global conflict, bodily movement and decorative painting.

Recent research on Knights by Rosanna Eckersley, Sacha Llewellyn and Lyrica Taylor has offered new interpretations of her work in relation to modernism, feminism, religion and British art in the twentieth century.4 This research, which was also extended and deepened in the exhibition Winifred Knights (1899–1947) at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery, curated by Llewellyn in 2016, builds on the scholarly territory regarding British mural paintings, decorative painting and the neo-romanticism of Edwardian and interwar Britain advanced by scholars including Emma Chambers, David Peters Corbett, Alan Powers and Lisa Tickner.5 The present investigation of Knights’s The Deluge adds to this growing corpus of material by offering additional potential sources for Knights’s inspiration for the painting, tying its production and meanings closer to theological perspectives, and charting new possibilities for contextual explication in relation to dance, war and gender.

Education and ambition

Winifred Knights was born in 1899 and grew up in London. She showed artistic skill from an early age, and her perspectives on art and life were strongly shaped by her aunt, Millicent Murby, who was a member of the Fabian Women’s Group and a campaigner for women’s rights.6 Knights won silver and gold medals from the Royal Drawing Society by 1915 and she was accepted as a student at the Slade the following year, when she was seventeen.7 Her first experience at the Slade had been several years earlier, in 1912, when she met Professor Frederick Brown and showed him her work; he encouraged her and suggested book illustration as a potential future.8 Yet by the time she had enrolled at the Slade full-time in 1916 it was evident that Knights had potential as an accomplished painter. That said, women at the Slade were treated variably, and gender politics could be problematic. As art historian Katy Deepwell notes regarding relationships between Slade students:

Sexual attraction was not the only reason for women competing for the attention of male students; association with certain male students might also be a way of gaining attention for one’s work. [Slade] Professor [Henry] Tonks was well known for his withering remarks to women students suggesting they were better suited to feminine pursuits of wool-work or needlework.9

In 1917 Knights experienced a serious trauma: she witnessed the catastrophic Silvertown TNT factory explosion and left London thereafter to stay in Worcestershire until the war ended.10 In October 1918, a year after her departure, she returned to the Slade and won the £16 Figure Composition Prize for that year; she also became a Slade Scholar.11 Yet the Slade to which she returned had changed substantially: many students had been killed, and artists’ lives, if not caught up with the battlefield, were economically precarious. Tonks was anxious about limited resources and as early as 1915 Knights’s contemporaries had been experiencing few buyers for their work, with income slowing to a trickle. That said, the market was to pick up again during the First World War and into the 1920s, along with a renewed sense of artistic creativity in the war’s wake.

Knights’s first major work, A Scene in a Village Street with Mill-hands Conversing (UCL Art Museum, London), occupied much of 1919, and this won the £16 Summer Composition Prize.12 Tonks decided to hang Mill-hands Conversing next to Stanley Spencer’s The Nativity 1912 (UCL Art Museum, London) in the Slade building to demonstrate the art college’s ability to train artists to work with challenging subjects encompassing history painting and contemporary themes.13 Knights’s style also stuck closely to the Slade’s method of linear clarity in drawing, which had been promoted in the late nineteenth century and carried forward by Tonks from 1892, when he first joined the Slade as Assistant Professor.14

In January 1920 Knights’s work was displayed alongside that of sixteen artists in the Grafton Galleries in London. On the basis of this exhibition, which included her Figure from Life 1919 (UCL Art Museum, London), Knights was selected to compete for the Rome Scholarship in Decorative Painting. According to the BSR, the scholarship was seen to be ‘the highest distinction of its kind in the Empire’,15 and Knights would be the first woman to win this prize with her epic painting The Deluge.

Preparation and painting

The BSR was founded in 1901 and the Rome Prize in 1912. One scholarship was awarded each year in several categories including painting, sculpture and architecture. At the time that Knights entered the competition, BSR scholarships lasted three years. The Rome Prize was usually open to British citizens under thirty years of age, but the age limit was raised to thirty-five for 1920 only, to account for the delay to their studies of those candidates who had participated in the First World War. The conditions of the 1920 prize were ‘to produce a painting in oil or tempera and a cartoon, though not necessarily the same size, the cartoon to be executed first and generally though not strictly adhered to in the painting. The size of the painting shall be 5ft x 6ft.’16 Along with Knights, the other finalists for the 1920 Rome Prize in painting were Arthur Outlaw, Leon Underwood and James Wilkie. Each of the four finalists was given studio space for six days per week, a £6 allowance for models and eight weeks to complete the painting. Knights created studies in watercolour and in oil, annotated sketches and drew many figure studies for all aspects of The Deluge.

Fig.2

Winifred Knights

First composition for The Deluge 1920

UCL Art Museum, London

Her preparatory works for The Deluge indicate that Knights initially planned a composition that placed the ark in the middle ground with Noah and God’s chosen few calmly waiting to climb aboard their vessel (fig.2). Sacha Llewellyn has likened the composition and affect of this first version to the serene and delicate style of artists such as Robert Anning Bell (1863–1933) and Walter Crane (1845–1915), whose work Knights would have known, the latter through her earliest work in illustration.17 In this first composition, the central figure in green, potentially modelled on Knights herself, looks behind her at the people and animals waiting to board the ark. The emotional ambiguity and gestural dynamism of this composition, together with the low hills populated with clusters of people, are the two elements that Knights kept in her final version of The Deluge. This first plan was ultimately abandoned by Knights in favour of ideas that were far less conventional, and that set her work apart from the other Rome Prize competitors. Among both the smaller and the more monumental preparatory works Knight undertook for the final painting, Knights’s full-scale cartoon for The Deluge (fig.3) is slightly different from the completed oil, which populates the desolate watery background with more figures, and the foreground with a running dog to emphasise the people’s state of panicky flight.

Fig.3

Winifred Knights

Full-scale cartoon for The Deluge 1920

Wolfsonian, Florida International University, Miami Beach

© The estate of Winifred Knights

Although she evidently read the biblical account of the flood closely in response to the Rome Prize’s brief, there is no evidence to suggest that Knights was religious. Her decision to change tack, to create a bolder and more ambiguous composition that took the subject matter in a modern new direction, portraying the reality of almost all living things being drowned, produced a tense drama rather than one necessarily fuelled by religious fervour. As it is described in the Bible: ‘Everything with the breath of life in its nostrils died’.18 The world’s tallest mountains were submerged, there was no air left to breathe, no food to eat, and the earth was uninhabitable for humanity. Destruction, in this biblical account, was total salvation for Noah’s select group. Vulnerable creatures without God’s special protection were not only condemned to death, but also not told their fate. As the world inexplicably swelled with water from above and below, Knights’s painting suggests, the full range of human emotional experience was painfully unleashed.

To make the final work, Knights prepared her canvas with an off-white ground, upon which she traced her underdrawing in pencil. Knights then painted the composition in thin layers of viscous oil paint, producing an effect that is opaquely matte but gives way to passages of translucency. Some areas were scraped back and revised during painting, which has caused minor cracking. Tate conservation reports indicate that there are small pinholes in the support that correlate to some of the painting’s architectural features.19 What can be gleaned from Knights’s working methods – the large numbers of figure studies that she made, particularly of heads, hands and feet, and the rate of production of her later paintings – suggests a meticulousness and hesitancy borne of perfectionism.

Visual influences

Fig.4

Hamo Thornycroft

Lot’s Wife 1878

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The gestures and patterns of the figures in The Deluge may be related to several art historical sources. The position of the central female figure’s hands, stretching outwards as she looks back, can be seen as a synthesis of the classic twisting motion of Lot’s wife in Genesis, glancing back before being turned into a pillar of salt, with one of the outstretched gestures painted frequently by Renaissance artists when depicting the Virgin Mary’s reaction to the Annunciation. For instance, Knights is likely to have seen Hamo Thornycroft’s 1878 sculpture Lot’s Wife (fig.4), and the dramatic diagonal pose, arms bent and hands raised, of Knights’s central female figure is the tragic gestural inverse of Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli’s image of the Virgin in his Cestello Annunciation 1489–90 (fig.5), which Knights would have known well.

Fig.5

Sandro Botticelli

Cestello Annunciation 1489–90

Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Since the aesthetic movement’s turn towards classicism in British art in the 1860s, an interest in Botticelli had emerged through painters including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Evelyn de Morgan and Walter Crane, and this attraction to Renaissance art and to the distinctive modelling and palette of Botticelli in particular continued to permeate the culture of young artists in the early twentieth century at the Slade, such as Knights. In Botticelli’s Cestello Annunciation, the Virgin’s and the angel’s hands suggest the future fulfilment of God’s salvation through the Incarnation of Christ, and in The Deluge Knights takes this well-known Renaissance image and invokes it by disordering it, opposing the direction of the hands and of the head. Botticelli’s interpretation of the Virgin’s acceptance of her role as the Mother of God becomes Knights’s representation of a young woman haplessly fleeing waters that will destroy all of humanity save a select few.

Fig.6

Nicolas Poussin

Winter (The Deluge) 1660–4

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Sacha Llewellyn has connected Knights’s treatment of the subject of the flood in The Deluge with additional sources in western art including Nicolas Poussin’s Winter (The Deluge) 1660–4 (fig.6) and Vittore Carpaccio’s St Jerome and the Lion 1509 (Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice).20 She does so largely at the level of gesture and atmosphere: Poussin’s dramatic contrasts of deep greys and bright moments of colour in the figures’ clothing, and the effort of lifting and receiving a vulnerable figure on the right; and Carpaccio’s powerful depiction of those fleeing in fear, especially in the pose of the monk immediately to the right of St Jerome.21 Llewellyn also argues that Knights drew on the Massacre of the Innocents 1451–2 (Museo di San Marco, Florence) by Fra Angelico when working on the figure of the mother and child in the foreground of The Deluge.22 As Llewellyn points out, Knights had also seen Andrea del Verocchio’s bronze sculpture Putto with Fish c.1470 (Palazzo Vecchio, Florence) and drew it in her preparatory sketchbook for The Deluge.23 As the artist wrote to her mother in 1921:

I love Florence it is much more alive and beautiful than Rome, and the mass of pictures!!! And lovely frescoes in the churches!!! … That beautiful little Babe with the Dolphin, the one I drew to send in for the Prix de Rome is here in the Courtyard of the Palazzo Signoria, it is a delicate and beautiful thing just like a butterfly.24

Fig.7

Giovanni Bellini

The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr c.1507

National Gallery, London

In addition to these sources, Knights would have also been able to study Giovanni Bellini’s The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr c.1507 (fig.7) at the National Gallery in London, which had come into the collection in 1870.25 In the latter work, the multiple levels of narrative and strong horizontality emphasise the scene’s violent intensity. St Peter Martyr was a Dominican monk ambushed on his way to Milan by heretics, who stabbed him to death. As told by Jacobus de Voragine in his collection of hagiographies the Golden Legend (c.1260), St Peter’s companion escaped to raise the alarm. In Bellini’s painting, woodsmen chop down trees, which bleed in sympathy for the dying saint, whose final act is to write ‘credo’ in the dust with his own blood. The figure that nearly does not escape from the murderous clutches of the knife-wielding soldier witnesses the death of his monastic brother as he flees, much like the women who look back in Knights’s The Deluge, bearing witness to destruction on a global scale.

The prize and its aftermath

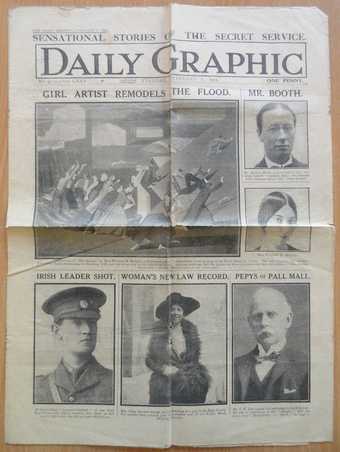

On 21 September 1920 Knights was informed that she had prevailed over fellow Rome Prize finalists Arthur Outlaw, Leon Underwood and James Wilkie, and was offered the prestigious scholarship to study and work at the BSR.26 Shortly after, on 6 October, the Sketch published a photograph of Knights to mark her Rome Prize win, reporting that her ‘appearance accords in every particular with the decorative canons laid down by the most up-to-date art circles’.27 The article erroneously referred to the artist as ‘Gertrude Knights’ twice, and gave no details about the painting. The Daily Graphic, which would later observe that Knights’s rendition of the ark was suggestive of modern concrete buildings, noted how this startling contemporary element was paired with the figures of ‘present-day men and women’, a feature that was regarded as one of its strengths.28

In a letter sent to her aunt upon winning the prize Knights wrote, ‘People seem sorry for men who didn’t win – why? They had just the same chances as I, and more.’29 At the Slade, although women artists outnumbered the men, few women rose to the top of their profession, and at the BSR Knights encountered outright opposition to her work and presence because she was a woman. J. Benson, another Rome Scholar, was hostile and Knights observed in a letter to her mother that he ‘does not respect women’.30 This was not everyone’s view, however, and Knights was also something of a guest of honour ‘because I am the first woman painter to gain the scholarship and the school is very proud of me’.31 Despite this there were very few women who went on to hold fellowships at the BSR in the first decades of the programme.32

The BSR’s Faculty of Painting comprised ten artists, many of whom were key mentors and sources of influence for Knights throughout her time there. They included Philip Wilson Steer, John Singer Sargent, George Clausen, D.Y. Cameron and W.B. Richmond. Knights had met Richmond the year before the Rome Prize competition through fellow Slade student Arnold Mason, who had been taught by Richmond. The latter was an important contributor to the decorative painting movement that characterised the Slade in the first years of the twentieth century. ‘Decorative’ as an art category had its roots in Edwardian public art commissions – decorative painting was effectively the treatment of a grand theme in a monumental way, drawing on the influences of early Italian Renaissance frescoes even if the modern result was radically different from the Italian models in composition and tone, and Knights’s The Deluge and subsequent BSR work has often been characterised according to this style.33

Fig.8

‘Girl Artist Remodels the Flood’, Daily Graphic, vol.125, no.97, 8 February 1921, p.1

In February 1921 the BSR held a Rome Scholars exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Knights’s The Deluge was displayed alongside the work of the other three finalists.34 The Daily Graphic commemorated this by publishing an image of Knights’s painting on its front page on 8 February 1921 alongside the headline ‘Girl Artist Remodels the Flood’ (fig.8).35 In 1925 The Deluge was displayed in the BSR’s section of the Paris International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Art; it was awarded a silver medal, and Knights was the only one of the BSR’s entrants to win a prize.36

Depth and temporality

As a meditation on the relationship between surface and depth, both compositionally and socially, The Deluge is complex. David Peters Corbett has argued that Edward Burne-Jones’s Laus Veneris 1873–5 (Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle) is a painting that glories in its ‘surface-ness’, suggesting that it is ‘all surface’, as sumptuous textures and glowing colours press up against the threshold between the canvas and the viewer.37 Knights’s painting, conversely, is all depth. What was on the surface, surrounded only by air and once habitable, is now in the process of increasing submergence below what can be seen and what is survivable. The liveable environment disappears as the world fills up with a substance that both gives life to humanity and takes it away. The water itself is suggestive of multiple depths and sensations, in places appearing fixed hard as steel and in others apparently as mutable and fluid as the thin yet viscous paint that Knights used to render it. Passages of the painting offer differing registers of time as the running bodies, frozen in motion, hair surging around a turned face like metallic, decorative waves, are poised between a threatening present and an imminently destructive future.

As mentioned, Knights’s treatment of temporality and mutability was not necessarily forged in relation to a deep personal theology. In this sense her work has a kinship with religious artwork by Burne-Jones and many in his circle, in which spiritual ideas were profoundly inspiring and considered with artistic intensity and care, although the personal sensibility of the artist was not necessarily in keeping with the theological themes of the work.38 The deluge was a set subject at the Slade, and although they mainly depicted religious subjects, Knights’s subsequent works, such as The Marriage at Cana 1923 (Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongawera) and Scenes from the Life of St Martin of Tours 1928–33 (Canterbury Cathedral, Canterbury), did not spring from an articulate and expressive Christian identity as they did in the case of her contemporaries David Jones and Stanley Spencer. Rather, these works, The Deluge principally among them, were opportunities to explore cultural history, to engage with commissions as well as the artistic imagination in a new way, and to probe both the conventions of history painting and the practices of decorative painting in and around her Slade circle.39 Knights’s work was paradoxically both at the very heart of the Slade method – as her multiple awards and strong relationships with Slade tutors bear out – and also pushed at its boundaries.

Rosanna Eckersley suggests that The Deluge is specifically connected to a return to, or at least a deep reflection upon, Knights’s traumatic experiences of the First World War, and that the painting is a metaphor for the war more generally.40 Perhaps, here, we encounter another critique regarding human experience and confusion regarding how and why suffering takes place. At the end of Genesis 8, when the flood has receded and Noah and the ark’s contents have decamped onto dry land, God makes a solemn promise: ‘I will never again curse the ground because of humankind, for the inclination of the human heart is evil from youth; nor will I ever again destroy every living creature as I have done.’41 Those who witnessed and commented on the scale of destruction in the First World War in theological and poetic writing, as the theologian Maggi Dawn outlines in her essay in this In Focus, were wrestling with the sheer scale of human tragedy and loss.42 Many may have wondered if God had indeed kept his promise. By focusing on those left behind, Knights refused a classic iconographical engagement with the biblical story of the flood without deviating from the scriptural account. Instead of the triumph of God’s union with Noah and subsequent pact with humanity – instead of the hope of salvation – Knights concentrated her artistic energy on the often untold plight of those left behind, dismissed in scripture as ‘corrupt in God’s sight, and filled with violence’.43 Knights does not show these people as corrupt, but as ordinary, credible, pitiable, and indeed shows them as herself, her family and her friends navigating the dangers and shifts in terrain that characterised modern Britain as light broke in through the thick clouds brought by the First World War.

Corrections were made to this essay in January 2018.