Winifred Knights’s work as a Rome Scholar at the British School at Rome (BSR) built on the foundation of success and artistic experimentation that she achieved with The Deluge 1920 (Tate T05532), combining these with the close study of Italian landscape, art history and material culture. In the early 1920s her interest in artists as diverse as Piero della Francesca (c.1415/20–1492) and Paolo Veronese (1528–1588) comingled with her absorption of more recent movements in British art, including the nineteenth-century Pre-Raphaelites and their circle, and indeed with Knights’s own modernist and more conservative contemporaries.1 Her work strongly identified with the methods and aesthetic of London’s Slade School of Art (where she studied in 1915–17 and 1918–20) and its prominent tutor Henry Tonks, specifically decorative painting – broadly defined as the treatment of a grand theme in a monumental way, combining the influences of early Italian Renaissance frescoes with a contemporary style consisting of pure, subdued colours and simplified, formal compositions and poses. Yet Knights’s work also pressed up against these traditions and techniques, pushing new artistic boundaries.

Despite the fact that there is no evidence of her holding strong religious views – the subject of the biblical flood in The Deluge was set by the organisers of the Rome Prize for which Knights created it – all of Knights’s major works following The Deluge were based on Christian themes, and all were connected with western art historical visual culture, uncovering new ground in the increasingly contested and diversifying field of history painting. Moreover, they continued an approach that Knights had begun in The Deluge: in each, the key moment of a well-known story (such as the presence of Noah’s ark, or Jesus’s command that turned water to wine) is deliberately not foregrounded. Instead of emphasising the dramatic moment in which a male biblical protagonist exerts power and leadership in a profound way, Knights focused on those on the margins of the main narrative. In doing so she complicated the meanings of these core Christian stories in ways that allowed the paintings’ viewers to find new forms of engagement with the text through theologically sophisticated modern images.

This essay considers The Deluge in conjunction with several paintings that Knights produced after 1920 – The Marriage at Cana 1923 (Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongawera), La Santissima Trinita 1924–30 (private collection) and Scenes from the Life of St Martin of Tours for the Milner Memorial Chapel at Canterbury Cathedral of 1928–33 – as a means of charting this distinctive approach to history painting and religious subject matter. It then explores the reception of her work in Britain and her connection with decorative painting.

Holiness and history painting: A new approach

Prior to beginning her primary BSR painting, The Marriage at Cana (fig.1), which depicts the story of Christ’s first miracle in which he turned water to wine, Knights visited Arezzo to study Piero della Francesca’s Legend of the True Cross cycle of frescoes at the Basilica di San Francesco.2 The Marriage at Cana can be linked with Piero’s Procession of the Queen of Sheba 1452–66 (fig.2) from the cycle in several ways: the clustering of figures in a setting on the threshold of the landscape; the formal, ordered spaces defined by sparse, geometric architectural features; and the approach to composition that places the action in multiple zones of the picture simultaneously. Furthermore, highlighting Knights’s characteristically provocative blend of old and new art historical references, art historian Rosanna Eckersley has compared the man resting on his back with knees bent in the left of Knights’s The Marriage at Cana with figures in Seurat’s paintings Bathers at Asnières 1884 (National Gallery, London) and his A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte 1884–6 (Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago).3 This connection with Seurat can also be seen in Knights’s recumbent and sitting figures, such as the individual seated with her back against the tree on the left that may be a portrait of the artist. Similarly, the figures occupying the mid-ground in the left of the composition, sitting between the vertical and horizontal stretches of tables covered in neat white cloths, connect the biblical theme of the Marriage at Cana with the modern leisure scenes depicted in the work of nineteenth-century French and British impressionist and post-impressionist painters, the latter including Seurat.

Fig.1

Winifred Knights

Marriage at Cana 1923

Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongawera

© The estate of Winifred Knights

Fig.2

Piero della Francesca

Procession of the Queen of Sheba 1452–66

Basilica di San Francesco, Arezzo

In The Marriage at Cana most of the guests in the painting are in modern dress, as in The Deluge. Christ, however, is dressed in a cassock-like tunic reminiscent of those seen in early Renaissance works of art such as the ones Knights studied at the BSR. The difference in dress between Jesus and the wedding guests emphasises his incarnational distinctiveness as holy miracle-worker. This is the moment of transformation from water to wine but, as in Veronese’s treatment of the same subject in his The Wedding at Cana 1563 (fig.3), not everyone is focused intently and devotionally on Jesus. For instance, the seated figure on the left that is likely modelled on the artist is shown sketching. She faces outwards into the wilderness, away from Jesus’s encounter with the wedding guests. This is arguably a meditation on another kind of miraculous creation: that of art itself. The artist in The Marriage at Cana is occupied with her labour and attention to nature such that the presence of Jesus and his miraculous activity is incidental and peripheral. Moreover, the serenity and stillness Knights has achieved through the palette, the delicate gestures, the calm atmosphere and the undramatic unfolding of the narrative regarding the water and wine, which takes place adjacent to the long banqueting tables, suggest an indebtedness more to Piero than to Veronese’s comparatively wild and chaotic party.

Fig.3

Paolo Veronese

The Wedding at Cana 1563

Musée du Louvre, Paris

© Musée du Louvre / Angèle Dequier

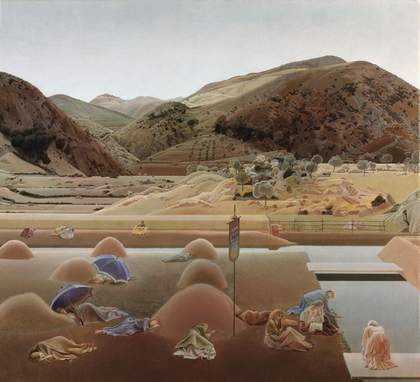

As paintings such as The Marriage at Cana imply, although history painting may have been eclipsed in the first decades of the twentieth century by the forceful adoption of modernism through Roger Fry, Clive Bell and their circle, it certainly did not disappear. Curator and art historian Emma Chambers has explained that ‘History Painting continued to prosper as public art, but distinctions between narrative and decoration became more fluid and its traditional emphasis on moral and intellectual content was often subordinated to aesthetic and visual qualities.’4 In the stillness of her compositions and palette ranges, Knights connected the traditions of history painting with her own unique handling of emotion and the senses. Touch, taste and sight are also keys to interpreting The Marriage at Cana, and many others of Knights’s paintings, which consistently contrast movement with stasis, and rest with labour. La Santissima Trinita, for instance, depicts Italian pilgrims resting in the countryside at Abruzzi on their way to the pilgrimage site of Vallepietra (fig.4).5 Unlike Knights’s other works based on biblical tales or a saint’s life, this is a surreal and dream-like rendering of an Italian religious practice that Knights would have witnessed during her time at the BSR. It is a genre scene that returns Knights to the territory of her earlier work including A Scene in a Village Street with Mill-hands Conversing (UCL Art Museum, London), which she completed in 1919, months before The Deluge. In La Santissima Trinita the religious banner declaring the holy purpose of these figures, its tall form standing guard among the umbrellas shading weary travellers who rest unselfconsciously in a hay field, is the only clue that this strange landscape is driven by a sacred theme.

Fig.4

Winifred Knights

La Santissima Trinita 1924–30

Private collection

© The estate of Winifred Knights

Fig.5

Winifred Knights

Scenes from the Life of St Martin of Tours 1928–33

Milner Memorial Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral, Canterbury

© The estate of Winifred Knights

The search for a new way of expressing holiness through a combination of modern and ancient motifs occupied Knights for over six years, through the making of her altarpiece for the Milner Memorial Chapel at Canterbury Cathedral, Scenes from the Life of St Martin of Tours (fig.5). Here, as with The Deluge, the local and the personal strongly informed a broader art historical horizon. Knights probably read Sulpitius Severus’s hagiography of St Martin (written in the years 394–6), which was the standard hagiography containing elements to which Knights refers in her altarpiece. Her painting is nonetheless unconventional in that it concentrates on St Martin’s monastic life and his miracle-working, literally marginalising the well-known story of his conversion, in which he gives half of his cloak to a poor and vulnerable man, to the far left of the composition. In doing so, Knights continued her earlier strategy, seen in The Marriage at Cana and The Deluge, of turning her artistic attention not to the core dramatic element of a given Christian narrative but to the moments and possibilities surrounding that narrative, in order to bestow new energy upon a familiar theme.

Decorative painting and the reception of The Deluge

A common trend in critics’ responses to Knights’s The Deluge – and one that could apply to the work she produced in the two decades following her BSR fellowship – was its resistance to easy categorisation. As the Daily Graphic observed of The Deluge when it went on display at London’s Royal Academy in 1921: ‘The picture might be Cubist or Futurist, but the critics will not have it that it is either. Some describe it as an example of anarchy in art, original, tragic, and inspiring [and] as something distinctly new and compelling in its treatment of a great theme.’6 The Daily Sketch called it ‘Futurist art’; the Morning Post praised its ‘cubistic principles’; and the Jewish Guardian described its ‘jerky cubist composition’.7 Art historians also picked up on this quality in Knights’s work. In 1924 C. Lewis Hind described The Deluge as ‘an ingenious and surprising adaptation of Cubism’.8 This was important in the context of the Slade: Professor Henry Tonks referred to post-impressionism as ‘The Deluge’, and his own practice, rooted in Italian Renaissance techniques and aesthetics, was set firmly against the tide of abstraction. For Tonks, post-impressionism and its successors constituted an ‘evil thing that had seduced the most gifted’ within the Slade.9

Despite the alluring inability to categorise The Deluge, Knights’s work throughout her career was associated with decorative painting due to her training at the Slade and her network of creative family and friends, especially her husband, muralist Thomas Monnington. Although she painted no murals herself, her circle comprised the loose but distinctive movement in early twentieth-century British art connected to interwar mural painting and its afterlife. Art historian Alan Powers notes that murals and decorative painting had an important part to play in this generation because they ‘were part of the transition between the ideals of the Victorians and the visual languages of Modernism’,10 while in 1914 the poet and critic Margaret Steele Anderson wrote that ‘the decorative, combined with the idyllic, is a leading and definite purpose in the English art of today’.11 Perhaps the most satisfying definition of decorative painting, at least in relation to Knights’s work, was published by artist Walter Crane in 1905: ‘a certain flatness of treatment with a choice of simple planes, and pure and low-toned colours, together with a certain ornamental dignity or architectural feeling’.12 Writing in the late 1920s, the artist Walter Bayes provided an even vaguer but no less true assessment of decorative painting in which he suggested that it was a case of looking to the Renaissance and being committed to advancing the cause of history painting.13

Decorative painting, history painting and the mural tradition were central to the painting programmes at the Slade and the BSR, and in the work of artists connected to these schools such as Knights, Monnington, Arnold Mason and Colin Gill, the serenity, expression of repose, muted fresco tones and geometrical rigour of the Quattrocento would be blended together with subjects ranging from genre scenes of agriculture and children at play to representations of epic historical events and religious narratives. From near-contemporaries like Paul Nash and Stanley Spencer to her immediate circle, Knights was surrounded by a (primarily male) group of Slade and BSR artists that were all striving for new forms of painting conscientiously responsive to the history of history painting itself.

Indeed, there are commonalities between the colour and composition of The Deluge and war works by Nash and Spencer from the months prior to Knights’s work on her painting.14 Knights particularly admired Spencer, stating that he was ‘the most wonderful painter in England, not even excepting [Augustus] John’.15 Art historian Sacha Llewellyn has pointed out that the palette of Spencer’s Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916 1919 (Imperial War Museum, London) is similar to the deep red and grey tones of Knights’s The Deluge, painted the following year.16 In a lecture given early in his career, Spencer discussed the relationship between narrative, painting and allegory in terms that share much in common with the invitation Knights’s The Deluge makes towards the viewer. Spencer said that there was the same kind of ‘absorption’ of attention in reading and in looking at art, and that this was ‘a legitimate and proper thing for a painter to aim at … and expect the spectator to enter into … I wish people would “read” my pictures’.17

Knights’s particular contribution to the reassessment of history painting in The Deluge and the key works that came after it is the way in which she was able to take the core of a theme – be it a biblical flood or contemporary Italian peasants on a pilgrimage – and work with it to reconfigure a conventional idea into a bright spark of new and often emotionally uneasy visual experience. Yet the destructive forces characterising The Deluge were never to reappear in Knights’s work in the same way again. The burnished metal-grey tone of the canvas punctuated by deep reds created a surface within which the modes of modernity in art could be in fruitful dialogue, as Knights created a practice as hospitable to cubism as to realist iterations of suffering, such as those seen in the work of war artists like John Singer Sargent. That said, elements of The Deluge’s distinctive artistic criticality and vision remained in Knights’s later work: figural painting in an inherited and innovatively redeployed modern style as pointed cultural critique; religious painting as a source of innovative meditation on gender and temporality; meticulousness and precision in production; and the act of working with the inheritance of western art history alongside the influence of her contemporaries.