Fig.1

Winifred Knights

The Deluge 1920

Tate T05532

In Winifred Knights’s painting The Deluge 1920 (Tate T05532; fig.1) figures are caught amid rising waters, arrested by Knights’s paintbrushes in mid-flight. They run for their lives despite the strong dramatic irony that they will not and cannot be saved, with the distant ark’s ghostly presence on the rising tide remaining silent as they suffer. These figures participate in a desperate and soundless dance of death as they cling to watery hilltops, haul each other’s bodies across stony barriers and race uphill towards higher ground. Knights’s The Deluge was in part a product of her interest in dance and theatre, as well as her awareness of the artistic potential of new approaches to the body in motion, one that she shared with artists such as Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Percy Wyndham Lewis. This essay considers Knights’s painting in relation to dance, making connections between her artistic practice and contemporary artists’ engagement with the culture of the moving body.

In 1918 the sociologist Max Weber had observed that one of the impoverishing factors in twentieth-century experience was its pervading sense of disenchantment. He wrote, ‘Precisely the ultimate and most sublime values have retreated from public life either into the transcendental realm of mystic life or into the brotherliness of direct and personal human relations. It is not accidental that our greatest art is intimate and not monumental.’1 Art historian David Peters Corbett has argued that the years following the First World War were ‘subject to a struggle of competing definitions [in art], the majority of which were marked by retreat, evasion, and concealment of modernity’s impact.’2 According to art historian Lisa Tickner, at this time a network of artists were labouring to ‘leave aside the salon theme of circling nymphs’, turning instead to dance imagery as a way of ‘staging an encounter between violence and sexuality, refusing absolutely the coy fleshiness of the salon nude in favour of something more imperious.’3 London’s Slade School of Art, the Rome Prize for which The Deluge was painted and the pedagogical structure and overall cultural values of decorative painting that were popular among Knights’s circle were, potentially, resistant to the ‘intimate’ aspect of modernity that Weber identified.

By presenting a story of human tragedy – the biblical narrative of the flood, a subject set by the prize’s organisers – in a way that cites a wider collective grief following the losses of war, and by doing so using the taut dynamics of rhythmic bodily action and drama, Knights’s The Deluge holds two aspects of modern artistic style in tension: the realist values of decorative painting seen in the work of artists like Colin Gill at the Slade, and the turn to a riveting abstract energy exemplified by artists such as David Bomberg. One form of painting referred back to the early Renaissance and the other broke away towards abstraction; yet both approaches heralded a new way forward for modern British art. However, recent research and exhibitions, such as Nash, Nevinson, Spencer, Gertler, Carrington, Bomberg: A Crisis of Brilliance, 1908–1922 at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London (2013), and Alexandra Harris’s book Romantic Moderns (2010), as well as the hints of Paul Cézanne (1893–1906) and surrealism present in new interpretations of the work of Eric Ravilious by Alan Powers, indicate that these apparently opposing forms of modernism in the arts in Britain were not as distinct and distanced from one another as some art historians have suggested them to be.4 As this essay will show, through her representation of the body in motion Knights’s work ranges across this territory, drawing upon both the wellsprings of art historical material and the innovation of her contemporaries.

Dramatic rhythms

In the first decades of the twentieth century Dalcroze Eurhythmics became popular in Britain, as did the Ballets Russes. The founder of Dalcroze Eurhythmics, Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, believed that multi-sensorial awareness could be refined and coherently interlinked through rhythmic movements performed to music. In February 1920 the Musical Times stated that the primary purpose of Dalcroze’s bridging of music and gesture was ‘to exhibit freedom in translating musical elements into rhythmic bodily movement’, and noted that the Dalcroze method was growing rapidly in Britain as an increasingly mainstream tool for musical education, such that Knights was likely aware of its theories and practices.5 Education in rhythm and pattern could, according to Dalcroze, produce effects wherein a better sense of one’s body could contribute to a more sophisticated and integrated connection with the surrounding world, both in nature and in human relationships.

The Ballets Russes, based in Paris but performing internationally from 1909 to 1929, created multi-sensory dance-scapes in collaboration with avant-garde artists, musicians and performers. The first Ballets Russes performance in London had been staged in 1911, such that Knights would have essentially grown up with their presence at the cutting edge of the art of European dance. She may have seen numerous Ballets Russes productions in London between 1919 and 1922, when the company performed there more regularly, and we know that Knights invited her sister Eileen to one of its productions at the Alhambra in 1919 – possibly Léonide Massine’s La Boutique Fantasque (The Fantastic Toyshop) – to thank her for sitting for The Deluge.6

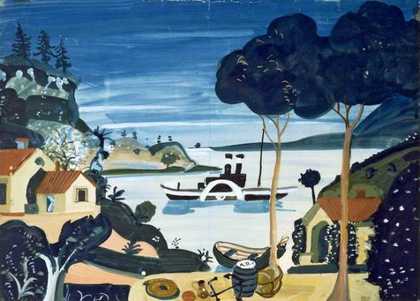

Fig.2

André Derain

La Boutique Fantasque 1919

Stage set design

The stage set for a key scene in La Boutique Fantasque (fig.2), designed by the painter André Derain, included a boat at sea set between the rolling hills of town and hillside, perhaps forming a source of inspiration for the composition Knights would conceive for The Deluge, especially when fronted by the rhythmic bodies of dancing figures on the stage. The swiftness and angularity of the fleeing figures in The Deluge also bear comparison with Igor Stravinsky’s 1923 ballet Les Noces, the choreography for which was closely connected with earlier Ballets Russes productions.7 Furthermore, Knights would have been familiar with magazines like Rhythm and Dancing Times, which were frequently illustrated with images of dancers, poses and designs.

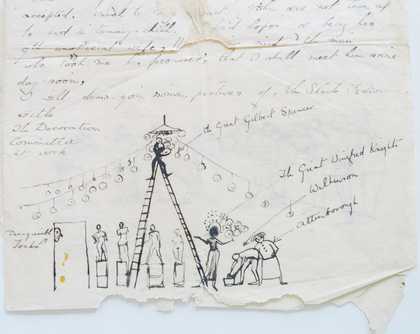

Fig.3

Winifred Knights

Illustrated letter from the artist to her mother Mabel Knights, 1919

Slade Archive, UCL, London

© The estate of Winifred Knights

In addition to her skills as a visual artist, Knights was also a dancer herself. Her early life’s correspondence and her letters from the British School at Rome suggest pleasure and confidence in performance and theatricality. While studying at the Slade, Knights was heavily involved in the art school’s social life. An illustrated letter from Knights to her mother in 1919 includes a cartoon of Slade professor Henry Tonks looking on as ‘the Great Winifred Knights’ hands inflated balloons to ‘the Great Gilbert Spencer’, both members of the decoration committee for a dance at the Slade (fig.3).8

There is evidence that Knights’s dedication to dance, theatre and performance continued during her time studying as a Rome Scholar at the British School at Rome in the early 1920s. In February 1921 she wrote to her mother and her sister Joyce about dances and a masked ball in which she participated enthusiastically.9 She had been to the Ballets Russes in Rome in January 1921, and the relationship between dance, theatre and the tempering stillness of Quattrocento art gave her paintings, particularly The Deluge and The Marriage at Cana 1923 (Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongawera), a peculiar quality of harmonic vibration.

Fig.4

David Bomberg

iv, from the series Russian Ballet c.1914–19

Tate P07011

© Tate

The strongly blocky diagonals and perpendicular arrangement of solids and voids in David Bomberg’s Russian Ballet book of six lithographs, published in 1919, also captured the sensation of the Ballets Russes (fig.4).10 Bomberg’s experience of the ballet performances informed the vibrant colour and energetic diagonal elements of these lithographs, and their dynamism was expressed in the words that faced the six images in the book:

Methodic discord startles …

Insistent snatchings drag fancy from / space,

Fluttering white hands beat – / compel. Reason concedes.

Impressions crowding collide / with movement round us –

– the curtain falls – the / created illusion escapes.

The mind clamped fast / captures only a fragment, for / new illusion.

Bomberg’s series was timed to be produced when the ballet came to London, with sets designed by Pablo Picasso and Mikhail Larionov, and were part of a wider phenomenon in which the Ballets Russes gripped London’s art scene and created new forms of interaction between dance and visual culture. Knights would certainly have been aware of the performance and very likely would have known this series by Bomberg, whose work was a stimulating presence in the British art scene during Knights’s formative years.

In addition to new phenomena in dance culture, Knights would have been aware of creative arenas of resistance to war. As art historian Grace Brockington has shown, pacifism and resistance to the political and social tragedies of war had its own aesthetic and was strongly connected to dance and drama.11 Knights’s representation of the flood in Genesis features figures in early twentieth-century dress whose stylised bodies produce a rhythm of turns, multiplications, replications and parallels across a canvas fragmented by syncopated diagonal and perpendicular blocks of matte colour. Additionally, patterns formed through repetition, doubling and visual rhythm and rhyme developed by Knights for The Deluge are also present in her later works, especially in the patterns of colour and arrangement of objects in The Marriage at Cana and La Santissima Trinita 1924–30 (private collection).

Anxious dances, vital gestures

Fig.5

Percy Wyndham Lewis

Kermesse 1912

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

© Wyndham Lewis and the estate of Mrs G.A. Wyndham Lewis

The dances of life and of death were often found to be surprisingly close together in the London cultural scene in the first decades of the twentieth century. At the famed cabaret club The Cave of the Golden Calf, Percy Wyndham Lewis’s painting Kermesse 1919 – with its startlingly bold blend of pleasure and violence, play and seriousness – took up some two-and-a-half metres of an interior wall. One of his studies for Kermesse, explored in depth by Lisa Tickner, brings conflict and rhythm into a dizzyingly close arrangement that vibrates with forceful energy (fig.5). Tickner describes its imagery of ‘sexual abandon’ as ‘menacing’. ‘There is no “background”’, observes Tickner of the work’s composition. Indeed, there are ‘only intersecting planes where – in contrast with Cubism proper – the manner of intersection is rendered violent’.12 In Lewis’s view, life was a constant struggle and combative dance was a pure artistic expression of this inherent truth.13 Knights’s view, expressed in visual art, could arguably have been less about an identification between life and violence, and more about an elision of vitality and serenity, even if that sense of Apollonian peace remained out of reach.

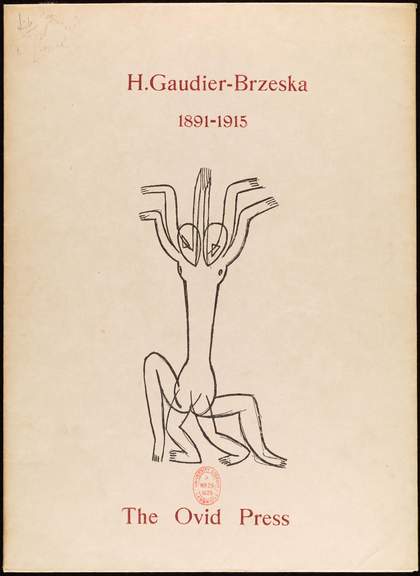

Fig.6

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Cover of 20 Drawings from the Note-books of H. Gaudier-Brzeska, London 1919

Cambridge University Library, Cambridge

Before he was killed in the First World War in 1915, the sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska repeatedly explored the blurred boundary between dance and battle.14 As the art historian Sarah Victoria Turner has observed, the interest in fighting and bodily movement also connected key modernists in British art including William Roberts and Duncan Grant.15 This wealth of activity focusing on the body in tense and combative motion took place in the years leading up to the First World War, when Knights was active as a young artist but not yet old enough or experienced enough to participate in the phenomenon. There is no doubt, however, that she was well aware of the work of artists such as Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill, Gaudier-Brzeska and their wider circle. Gaudier-Brzeska’s work was also illuminated afresh in 1919, only months before Knights made The Deluge, in an edition of twenty drawings published by Ovid Press, which included an arresting image of a female dancer modelled on the artist and writer Nina Hamnett, her figure lithe and taut, pulsing with economical curvilinear forms (fig.6). Similarly, the paradoxical tension between energetic movement and hard-edged solidity that Knights captured in The Deluge was, in part, a product of the fusion between two types of art. As the curator and art historian Emma Chambers writes about Knights’s painting, ‘Despite the dramatically decorative effect of its composition, the viewer’s interaction with this painting comes full circle back to the early ideals of History Painting in its clear narrative, easily read interaction of figures, and restricted use of colour and background.’16

In parallel with the work of American dancer Isadora Duncan, who offered new and radical approaches to the body as a means of expression in the first two decades of the twentieth century,17 dance, politics and visual culture came together in vigorous union in Vernon Lee and Maxwell Armfield’s 1915 book The Ballet of the Nations: A Present-Day Morality by Vernon Lee with a Pictorial Commentary by Maxwell Armfield. Knights’s work, Armfield’s ideas and Duncan’s dances can be seen as a constellation of intersecting points that account for some of the gestural motifs in The Deluge. As Grace Brockington points out, Armfield’s classicist illustrations, which initiate strong and sometimes contradictory dialogue with Lee’s text, have received limited academic attention, and the reception of The Ballet of the Nations included criticism of what Brockington has referred to as Armfield’s ‘exaggerated avoidance of the brutal’.18 Yet what is implied by such scenes is clear, just as it is in The Deluge: Brockington notes how allegorical characters surge through political discourse surrounding the horror and chaos of war. Characters are both amplified and paradoxically removed from the harsh reality of violence in the stylised classical figuration that combines Greek design with artistic lessons from its inheritors, especially Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) and Charles Ricketts (1866–1931). The ballet took up the trope of violence in war – a theme so central to the work of Lewis and Christopher R.W. Nevinson, and the official war artists more widely – and created a specifically classical framework for a strongly contemporary subject.

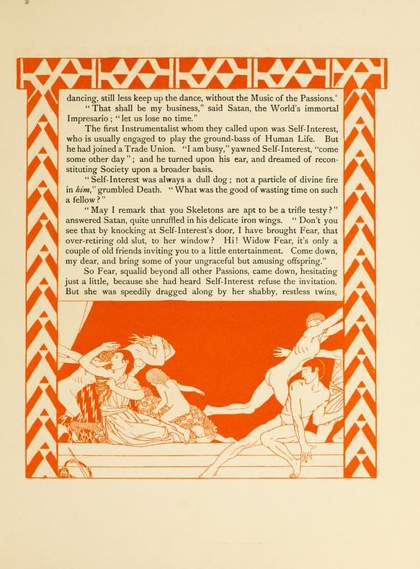

Fig.7

Maxwell Armfield

‘Fear, Suspicion and Panic’, from The Ballet of the Nations: A Present-Day Morality by Vernon Lee with a Pictorial Commentary by Maxwell Armfield, London 1915, p.2

Fig.8

Maxwell Armfield

‘The Meteor Curve of a Shell’, from The Ballet of the Nations: A Present-Day Morality by Vernon Lee with a Pictorial Commentary by Maxwell Armfield, London 1915, p.13

In The Ballet of the Nations, for instance, characters with names such as Self-Interest and Widow Fear interact in a raging landscape of topical themes. Armfield’s plate ‘Fear, Suspicion and Panic’ (fig.7) shares formal elements with Knights’s The Deluge: its nude bodies flee, consumed by anxiety, creating a strong diagonal thrust across the composition. In Armfield’s ‘The Meteor Curve of a Shell’ (fig.8), the crouching figure in the left of the diagonal grouping, with its body thrust forward, elbows bent, hands raised, head turned back and mouth open, is a possible model for the pose of the central figure in The Deluge. Armfield’s image is itself an allegory of the effect of an explosion in which, as Lee’s commentary states, ‘Backwards and forwards moved the dancers in that changing play of light and darkness and undergoing uncertain and fearful changes of aspect.’19 Armfield also worked with biblical imagery, and the wild gestures of praise and supplication in Miriam of 1919, depicting the Old Testament prophetess, have a visual affinity with Knights’s approach to figures in The Deluge as they run, lifting their arms to heaven.20

Fig.9

Duncan Grant

Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound 1914

Gouache and watercolour on paper on canvas

Tate T01744

© The estate of Duncan Grant

Photo © Tate

Developments in modern abstraction – specifically cubism and the work of Paul Cézanne – may have assisted in striving for this effect, together with the repose favoured by British School at Rome and Slade artists who drank deeply from the well of the Quattrocento. Picasso’s set and costume designs for the Ballets Russes, and his work on the two-act ballet The Tricorn Hat in London in 1919 in particular, may well also have been familiar to Knights. In addition, Knights may have been influenced by the abstract art produced by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant in 1914–15 that experimented with diagonal volumes and set them hard-edged together (see, for instance, Duncan Grant, Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound 1914, Tate T01744; fig.9). This, in addition to many of the textile designs produced by Bell, Grant and Roger Fry at the Omega Workshops – connected as they were with the political grit of pacifism as well as the pleasure of collaborative art-making – bears comparison with Knights’s handling of volumetric elements in The Deluge. These contribute to the sense of rhythmic movement in her figures, as well to the set-like theatricality of layers of grey, built up between cloud, water and earth. It is this tension between repose and tireless energy that delivers the ancient yet modern message of turmoil and helplessness in The Deluge; furthermore, one of the most powerful means by which Knights produced work that hovered in this way between the avant-garde and convention was through her attention to the contemporary world of European dance.

Fig.10

John Nash

‘Over The Top’. 1st Artists’ Rifles at Marcoing, 30th December 1917 1918

Imperial War Museum, London

© IWM (Art.IWM ART 1656)

In Knights’s The Deluge, violence is tempered with a sense of equanimity that plays out largely through the gestural harmony of the bodies themselves as well as the limited palette. Even this is on edge, however: while the central figure, modelled on Knights herself, is dynamically and energetically balanced in a pivot at the pelvis, her face registers stylised horror rather than peace. This is akin to Brockington’s observation that John Nash’s treatment of the soldiers in ‘Over The Top’. 1st Artists’ Rifles at Marcoing, 30th December 1917 1918 (fig.10), whose bodies push across a snowy trench in a scene of determination amid death, ‘recalls the men’s vulnerability and hopeless courage as they walk’, with Nash’s painting creating a ‘visual affinity between man and nature that is simultaneously elegiac and degrading’.21 Knights’s image is not war art per se, just as it does not directly inhabit the immediate context of avant-garde dance. Suspended between the pressures of topical violence on a world scale and the distinctive character of emergent art forms, Knights’ painting captures the experience of many women caught up in the First World War, experiencing it deeply and directly, and yet inhabiting social spaces on the periphery of the brunt of the conflict.

By mixing modern dress and the tense angularity of Ballets Russes moves with the Hellenic languidity of Renaissance painting and the repetitive patterns of Dalcroze Eurhythmics, Knights’s The Deluge achieves a visual amalgamation of the bodily phenomena circulating in and around London in the years between 1910 and 1920, with the punishing horror of war in between. Not strictly classicist, nor vorticist, and not relying on the aesthetic of the Bloomsbury artists such as Bell, Grant and their circle, Knights’s work offers a distinctive vision of biblical destruction. The way in which this is presented is ultimately pessimistic: the dancers will die, since vital rhythm is not enough to abate or quell God’s destructive forces.