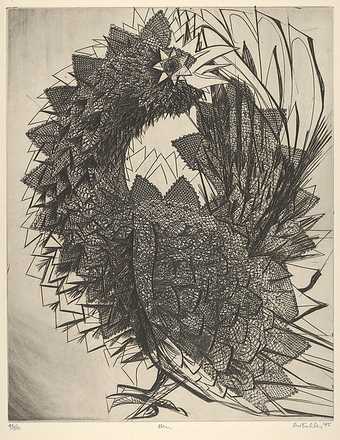

Fig.1

Sue Fuller

Hen 1945

Soft-ground etching and engraving

379 x 297 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Estate of Sue Fuller

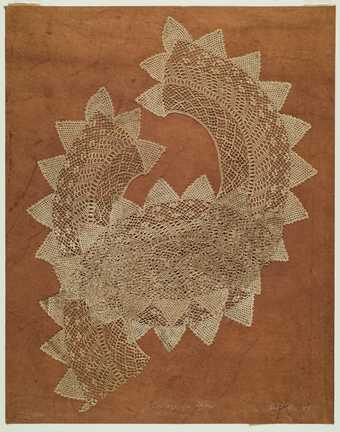

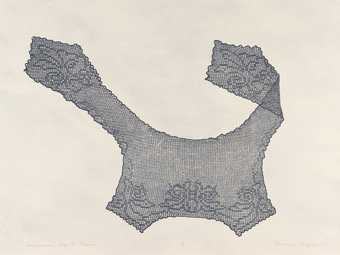

In 1946 Sue Fuller’s engraving and soft ground etching Hen 1945 (fig.1) won first prize in the Graphic Arts Show held at the Village Art Center in Greenwich Village, New York. The award afforded Fuller the opportunity to mount her first solo exhibition just a few months later at the same venue.1 There she showed a group of almost thirty prints, which she had produced since becoming a member of Atelier 17, the avant-garde printmaking studio located in New York between 1940 and 1955. The selection showcased Fuller’s great innovations as a printmaker and, in particular, her radical reimagining of soft ground etching, an intaglio printmaking technique. As can be seen in the preparatory collage for Hen featuring a Victorian lace collar (fig.2), Fuller applied textiles and fibre as a primary pictorial element. Both the print and the collage highlight Fuller’s ability to think innovatively when deploying the centuries-old practices of lace-making and soft ground etching.

Fig.2

Sue Fuller

Collage for Hen 1945

Lace on paper

Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California

Courtesy of Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

© Estate of Sue Fuller

Despite her trailblazing vision, the critical response to her 1947 solo show was, at best, mixed. In his report for Art Digest reviewer Alonzo Lansford described Fuller’s work as derivative of Atelier 17’s founder Stanley William Hayter (1901–1988), a tactic that was, and continues to be, common in attributing the accomplishments of women artists to the influence of a male master. Most other commentary took exception to her application of lace, fabric and textiles in soft ground etching. Lansford complained, ‘she does tricky things with string, netting, etc’.2 And Karl Kup, longtime curator of prints at the New York Public Library, issued a more nuanced critique of Fuller’s approach in his review for Print, a quarterly journal devoted to the graphic arts. He undercut her innovations by claiming her prints showcased ‘the most unacademic application of techniques’ and employed ‘techniques to her own liking’.3

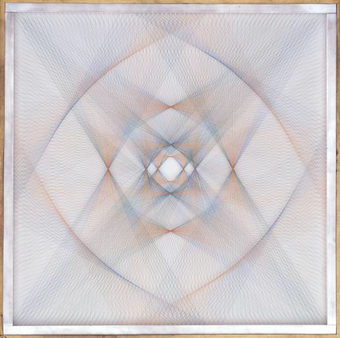

Fig.3

Sue Fuller

String Composition 128 1964

Plastic threads, wood, fabric and metal

914 x 914 x 38 mm

Tate T00757

© reserved

The subtext of these reviews suggests a consistent level of uneasiness with Fuller’s innovative execution of soft ground etching.4 Indeed, her prints were radically different from any other prints being made at this time, either at the Atelier 17 studio or elsewhere in the United States. Up until this point, soft ground etching was normally employed for transferring a drawing or achieving areas of shadow and contrast. Unconventionally, Fuller produced prints by collaging fibre and textiles onto metal printing plates, sometimes without marking lines on the plate with traditional tools like the etching needle or engraver’s burin.5 Her experiments in soft ground etching led directly to the development of her later three-dimensional string-wrapped pieces, of which the Tate’s String Composition 128 1964 (fig.3) is an extraordinary example. While discussing Fuller’s progression from printmaking to these string compositions, this essay will also establish her pioneering theories about soft ground etching as a form of collage, which she argued existed long before the emergence of the cubist collages of the early twentieth century, such as those made by Pablo Picasso or Georges Braque. The innovative prints made by Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) provided the creative spark to Fuller’s imagination, inspiring her extensive experimentation with fibre and textiles in soft ground etching and spurring her to write an important essay about Cassatt’s use of this particular printing technique.6 Fuller believed that soft ground etchings, no matter what their subject matter or stylistic bent, were collages on metal plate. This theory had a wide-reaching influence on other Atelier 17 members and later generations of artists and art historians. In particular, Fuller’s ideas presciently anticipated the concept of feminist collage, also termed ‘femmage’, in the 1970s.

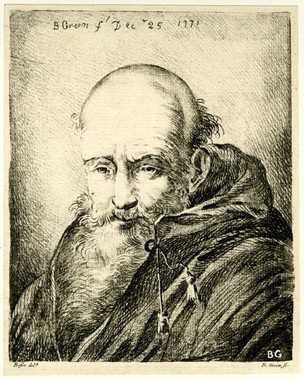

Fig.4

Benjamin Green after Benigno Bossi

Head of a Monk 1771

Soft-ground etching

146 x 117 mm

British Museum, London

A technique for converting freehand drawing to metal printing plates, soft ground etching has roots dating back to the eighteenth century. For more than two hundred years, from the initial discovery of etching in the late fifteenth century, the intaglio process relied on the application of an etching ground – a layer of acid-resistant material, such as varnish, resin, or asphaltum – which hardened over the surface of a metal plate. Using a sharp needle tool, printmakers scratched designs into this hard ground layer, exposing areas of the metal plate beneath, which were then attacked or ‘bitten’ when submersed in an acid bath. In 1771 British printmaker Benjamin Green devised a new method for etching, whereby the ground he applied to the metal plate remained sticky due to the addition of wax or grease (fig.4).7 With a sheet of paper laid over the prepared plate, Green drew an image with a blunt stylus like a crayon or blunt pencil. The pressure he applied to the paper transferred areas of the sticky soft ground from the plate on to the verso of the paper, exposing the metal plate’s surface to acid bite. Using this approach, Green was able to execute freehand drawings more quickly and autographically than was possible with the needle tool used in traditional hard ground etching.

Fig.5

Stanley William Hayter

Combat 1936, published 1941

Engraving and soft-ground etching

400 × 492 mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2018 Stanley William Hayter/ ARS, New York / ADAGP, Paris

Soft ground etching was very popular, mainly in England but also elsewhere, until c.1825, although the practice continued throughout the nineteenth century.8 Belgian artist Félician Rops, for example, began experimenting with soft ground etching in the 1870s and carried the technique one step further by impressing natural objects like plant material into the ground – a practice that has great relevance for Fuller’s work. In the late nineteenth century the technique was further adopted in France and Germany, particularly among artists using impressionist techniques. Knowledge of soft ground etching among French master printers and printmakers may have influenced the initial adoption of the technique by members of Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17 during the workshop’s earliest years in Paris, where it was located from the 1920s until the outbreak of the Second World War. Although engraving was the primary thrust of Hayter’s pedagogy, by the mid-1930s workshop members were experimenting with impressing textures into soft ground etching. Hayter used soft ground to create areas of shadow on his plates, exemplified by the crinkled tissue paper on the left-hand side of his masterful Combat of 1936 (fig.5).9 Leonor Fini, who worked briefly at Atelier 17 in the early 1930s, made soft ground etchings with a slightly different emphasis, cleverly impressing netting to represent the patterned dresses of her cartoonish figures.

Sue Fuller already possessed a very robust knowledge of printmaking techniques by the time she came to Atelier 17 in the autumn of 1943, three years after Hayter had relocated the studio to New York. Mastering the soft ground etching process had eluded her during her student days at Teachers College, Columbia University, with the printmaker Arthur R. Young, her favourite teacher. Although Fuller was always quite resourceful and willing to consult printmaking manuals like her ‘bible’, E.S. Lumsden’s The Art of Etching (1925), she had heretofore not been able to identify the right agent to soften the etching ground and produce successful soft ground etchings. Once Hayter gave her access to this trade secret – beeswax was the right ingredient – Fuller began researching soft ground etching, ‘seeking more understanding [of the] use of [textures] than had yet been tried’.10 Her experiments in soft ground techniques fall into two rough categories: first, semi-representational prints created by impressing pre-made lace and fabrics stretched into positions, as is the case with Hen; and second, abstract images made by interweaving strings and other fibres, as can be seen in The Sailor’s Dream 1944, illustrated below (fig.9). This evolution towards working with deconstructed textiles in soft ground etching would directly impact the formulation of her three-dimensional wrapped string compositions.

For her first type of soft ground etchings, Fuller took inspiration from the trove of lace odds and ends that she inherited when her mother died in 1943. Among her mother’s collection of lace, Fuller discovered a partially worked Arabian lace collar, which had been a popular needlework project for American women around the turn of the century. As can be seen in the collage for Hen (fig.2), which she kept as a teaching aid, Fuller cut the collar to form the body and triangular feathers of the chicken and impressed the lace design into a soft ground plate. She further elaborated the hen’s anatomical details by engraving spiky lines for the bird’s beak, feet, tail, as well as additional feathers. Although Fuller’s experiments with lace in Hen have a basis in her mother’s Victorian femininity, her method of working with such textiles broke with these traditions. Cloth and fabric usually have a unifying social purpose, especially at transitional moments in life like birth or death when they are passed through generations.11 Yet Fuller’s radical cutting of the lace into fragmented pieces, both paid homage to and completely undid the hours her mother spent creating the collar. Fuller’s use of these fabrics caused them to accumulate a brown, sticky residue from the soft ground as they were pressed into the plate, ruining them and forever divorcing them from their original decorative purpose as feminine ornamentation.

Fig.6

Mary Cassatt

The Visitor c.1881

Soft-ground, aquatint, etching, drypoint and fabric texture

397 x 308 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Despite the gendered connotations of lace and fibre, Fuller firmly believed that her textile-filled designs for soft ground etching were far from feminine crafts. In 1950, Fuller wrote an article for the Magazine of Art, in which she examined Mary Cassatt’s experimental practice with soft ground etching and argued for the connection between this printmaking process and collage.12 Among other examples, Fuller pointed to several textures within two impressions of The Visitor c.1881 (fig.6), which were housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a collection she visited often to understand printmaking’s historical techniques.13 An early version shows Cassatt impressing what Fuller called ‘nubbly material’ for the dress of the central figure. Cassatt also vigorously shaped the seated figure on the right of the picture with scribbles from the end of a paintbrush and strokes of stopping-out varnish. In other prints, Fuller believed Cassatt executed a drawing over scraps of netting, suggesting it was ‘the kind of fabric any Victorian lady whose dressmaker made her clothes and left cuttings of materials around would have in abundance’.14 Praising this process as ‘so direct, so complete, so simple’, Fuller believed that Cassatt’s soft ground etchings anticipated the ‘discovery’ of collage in the first decades of the twentieth century: ‘In this way, Mary Cassatt used the impression of the texture of materials in a print – a “collage” technique in the metal-plate medium – as early as 1881’.15 In this important statement, Fuller conceptualised soft ground etching in a revolutionary new way, as a forerunner to modernist collage. Even though the final printed sheets do not have any material glued to them, as found in collages as they are traditionally defined (‘collage’ comes from the French verb coller meaning ‘to glue’), a fundamental step in creating the soft ground etching nevertheless involved arranging scraps of paper, fibre, or other found objects onto a metal plate. Fuller knew that her article not only carried revolutionary significance for the print world, but also framed Cassatt’s artistic legacy in a new and more innovative way.16

Fig.7

Janet Lee Kadesky Ruttenberg with Sue Fuller and Donn Steward, after Mary Cassatt

In the Omnibus 1975–7 (state proof)

Soft-ground etching in black, green, brown and red on white wove paper

378 x 270 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.8

Janet Lee Kadesky Ruttenberg with Sue Fuller and Donn Steward, after Mary Cassatt

In the Omnibus 1975–7 (finished print)

Drypoint and soft-ground etching printed in colour

378 x 270 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

So confident was Fuller about her hypothesis that, in the 1970s, she spearheaded a hands-on project to prove that the tonal areas of Cassatt’s famous colour etchings from 1890–1 were made with soft ground etching. Fuller’s basic contention was as follows: because Cassatt had used soft-ground etching regularly from the 1880s she would have been inclined to stick with this familiar, direct process for the colour prints – using newspaper pressed into soft ground to create the grain – instead of switching to aquatint, a far more complex and intensive technique. Fuller initially broached this idea with Adelyn Breeskin, a Cassatt scholar and director of the Baltimore Museum of Art, in the late 1940s. The two corresponded immediately after the publication of Breeskin’s catalogue raisonné of Cassatt’s prints. In this first edition, published in 1948, Breeskin classified the 1890–1 prints as having ‘color areas applied on an aquatint ground’ and noted that the aquatint was of the ‘finest grain’.17 Congratulating Fuller on her recently released article in the Magazine of Art, Breeskin wrote ‘if by any chance the Cassatt catalogue should ever have a re-run, I’ll revise it to include your discoveries’.18 The 1970s became just that moment for Fuller to prove her theory. Breeskin was preparing for the second edition of the catalogue raisonné to be published in 1979. Meanwhile, Perry Miller Adato, a filmmaker working on a documentary film about Cassatt, approached Fuller about her 1950 article.19 Collaborating on this project with artist and friend Janet Ruttenberg and master printer Donn Steward, the group attempted to replicate Cassatt’s La Coiffure and In the Omnibus (figs.7–8) by impressing newspaper stock onto soft ground to obtain a delicate grain for the coloured areas.20 After some trial and error they produced stunning results, and Breeskin updated the technical designation of the 1890–1 colour prints in her revised Cassatt catalogue to include the possibility of the tonal areas being the result of either aquatint or soft ground.21

Even after Breeskin’s revision – grounded in the recreation by Fuller, Steward and Ruttenberg – the colour prints continued to be the subject of much academic debate, stimulated by Fuller’s research. In her 1980 monograph on Cassatt, the art historian Griselda Pollock mentioned the ‘considerable doubt about how Cassatt achieved her remarkable effects’, while simultaneously drawing on Fuller’s 1950 article to support a feminist reading of Cassatt as a pioneering technician.22 A few years later in preparation for a major exhibition and catalogue about Cassatt’s colour prints in 1989, art historians Nancy Mowll Mathews and Barbara Stern Shapiro examined the 1890–1 prints under high-powered microscopes and rolled back both Breeskin’s and Fuller’s revised findings in favour of an exclusively aquatint technique.23 Setting aside these technical arguments and any lingering doubt, it is simply important to register the enormous impression that Cassatt’s prints made on Fuller. Almost single-handedly, they energised Fuller to experiment enthusiastically with collaging patterns and lace onto her Atelier 17 prints and consider the use of fibre beyond printmaking.

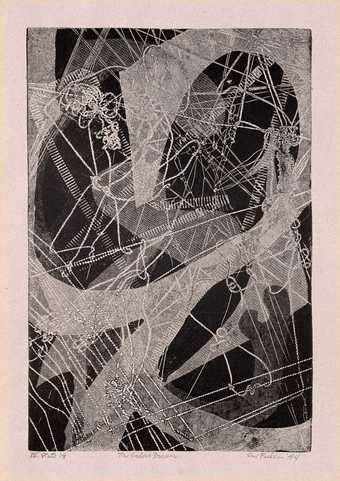

Fig.9

Sue Fuller

The Sailor’s Dream 1944

Soft-ground etching printed in relief

226 x 151 mm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© Estate of Sue Fuller and the Susan Teller Gallery, New York

Fig.10

Sue Fuller

Collage for The Sailor’s Dream 1944

Ribbon and string on paper

270 x 190 mm

Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum, Boston

© Estate of Sue Fuller

After her initial forays into the use of pre-fabricated lace for prints like Hen, Fuller further expanded the potential of collaging fibre on metal plates with her second type of soft ground etchings, which led directly to the creation of wrapped string compositions. While at Atelier 17, she quickly became frustrated with the limitations of stretching prefabricated materials to her desired specifications, lamenting ‘their immobility became exasperating’.24 Fuller reasoned, ‘if someone else could make up a material … then what was stopping me from reducing material to its least common denominator – a string and making my own material’.25 Ultimately, she pulled apart textiles and recombined their component parts – strings – into her own modernist compositions. Fuller’s second type of soft ground etchings, which she called ‘string doodles’, gave her a creative boost and signal a major shift in her aesthetic. Unlike the prints made from manufactured or vintage fabrics, which typically represented animals and human figures, the ‘scribbles in thread’ propelled Fuller toward abstraction. The Sailor’s Dream perfectly conveys Fuller’s mission to use threads to weave her own abstract textiles (fig.9). Strings criss-cross the print, often looping around one another or forming knots. The collage Fuller developed for this print reveals the variety of different types of thread ranging from cotton cording to thin sewing thread and even a red giftwrap ribbon that Fuller noted produced a ‘marvelous … thread-look’ (fig.10).26

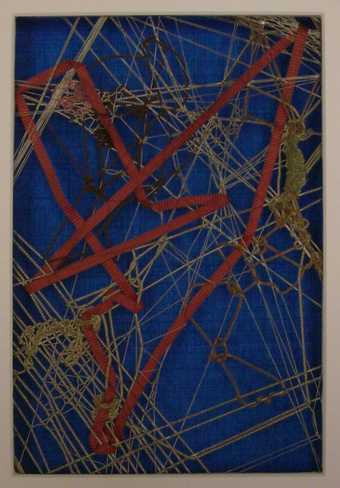

Fig.11

Sue Fuller

String Composition 63 1955

Polypropylene thread construction

851 x 1143 mm

Carnegie Museum of Art

© Estate of Sue Fuller

The Sailor’s Dream collage anticipates Fuller’s move away from printmaking to the string compositions that would engage her for the rest of her career. The fact that Fuller kept the collage for The Sailor’s Dream is not unusual; she kept many other preparatory collages to display next to the finished prints as teaching tools, as was also the case with Hen. But the way she preserved the collage for The Sailor’s Dream by mounting it on a bright blue background is significant for her development. In 1946 Fuller began making standalone pieces for which she wrapped silk, hemp, cotton sewing threads, upholsterer’s cord, fisherman’s seine, twine, and metallic threads around open frames with pegs placed at regular intervals. The compositions varied in colour from monochromatic white or muted tan tones to those with an array of bright colours. The process evolved over the more than thirty years that Fuller made three-dimensional string compositions, from wooden and metal frames to encased plastic blocks. In the first ten years of producing string compositions, however, Fuller struggled to define the works as either paintings or sculptures, a binary perpetuated by post-war museums. She eventually affixed coloured backing to them and hung them as paintings, an example of which is String Composition 63 (fig.11), acquired by her alma mater at the Carnegie Museum of Art. The relationship between the coloured backing of the preserved collage for The Sailor’s Dream and works like String Composition 63 is unmistakable. In fact, in Fuller’s application for a second Guggenheim Foundation grant in 1963 (she had previously been a recipient in 1948) she categorised The Sailor’s Dream as an, ‘early string composition’.27

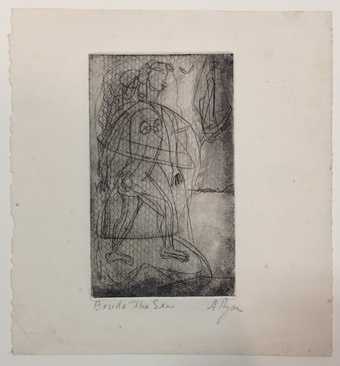

Fig.12

Anne Ryan

Beside the Sea c.1944

Etching and soft-ground etching

126 x 75 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig.13

Anne Ryan

Number 319 1949

Cut and torn papers, fabrics, gold foil and bast fibre on paper, mounted on black paper

197 x 171 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fuller’s theory of soft ground etching as avant-garde collage had a wide-reaching impact on other members of Atelier 17. Anne Ryan was a colleague whose time at Atelier 17 overlapped directly with Fuller in 1943. As correspondence between Fuller and Ryan demonstrates, the two women were on friendly terms.28 Ryan’s best-known work, the collages that she produced from 1948 until her death in 1954, owe a great debt to her contact with Fuller and training in soft ground etching. Although viewing an exhibition of Kurt Schwitters’s collages at the Pinacotheca Gallery in 1948 is almost uniformly cited as the inspiration for Ryan’s collages, the parallels between soft ground etching and collage, as Fuller advocated, primed Ryan’s later work.29 Ryan admired Fuller’s lace-filled soft ground etchings – she owned an impression of Fuller’s print Emperor’s Jewels from 1944 – and her experiments with fabric textures in printmaking have a similar basis in collage. Ryan saw the creative possibilities of collaging overlapping or adjacent fabric textures into soft ground, as can be seen in prints like Beside the Sea c.1944 (fig.12), which was among the first intaglio prints she made at Atelier 17. In this surrealist image where a woman walks down a beach, a layer of fine mesh from a silk stocking sits underneath a more open hexagonal pattern from fishnet stockings. Scraps of fishnet stockings would later appear in Ryan’s collages such as Number 319 from 1949 (fig.13). Because the textures of the fabric were transferred indirectly onto the paper via soft ground, acid bite and ink, Ryan’s prints show only an indexical trace of these fibres and it is easy to forget they have a similar basis in real materials. Just as Fuller advocated for Mary Cassatt’s soft ground etchings as collage, Anne Ryan’s etchings are full collages on metal plate and have multiple, complex component layers.

Beyond the walls of Atelier 17, Fuller’s theorisation of soft ground etching as a form of collage with textiles anticipated the articulation of similar views and the coining of the term ‘femmage’ by artists Miriam Schapiro and Melissa Meyer more than twenty-five years later. In 1978 Schapiro and Meyer collaborated on an influential article for the feminist journal Heresies that called attention to the politicisation of collage in art historical writing on modern art.30 Although mainstream art historians admitted the collage aesthetic had roots dating back prior to Picasso’s and Braque’s decisive ‘discovery’ in 1912, they nevertheless discounted the efforts of artists working in collage who they pejoratively called housewives and schoolgirls. To counter this masculinist and exclusionary narrative, Schapiro and Meyer synthesised a definition for ‘femmage’ to encompass the historical and pioneering efforts of female makers in developing collage. Aspects of femmage resonate directly with Fuller’s approach to soft ground etching, particularly her collecting and reuse of special family heirlooms in prints like Hen and Emperor’s Jewels. In addition to being a retroactive example of a femmage artist, Fuller was at the forefront of identifying and conceptualising the gendered history of the practice.

Fig.14

Miriam Schapiro

Anonymous Was A Woman IV 1977

Soft-ground etching in blue on white wove paper

460 x 603 mm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

© Estate of Miriam Schapiro/DACS 2018

Although Fuller tended to be a loner and was not actively involved in the feminist movement, there was nonetheless awareness of her practice in feminist circles.31 In what had to be a nod to Fuller, Miriam Schapiro made two sets of lace-filled soft ground etchings, both of which were called Anonymous Was a Woman: eight prints were issued in 1977 as a collaboration with students at the University of Oregon and eight published with Matrix Press in 1999.32 The lace collar featured in one print from the earlier series (fig.14) provides a feminist counterpoint to Fuller’s Hen. The collar stands on its own in Schapiro’s print, not twisted and reshaped to form an animal, but as a symbol of the historic inequality and under-recognition of women’s crafts. Fuller’s soft ground etchings and wrapped string compositions were clearly not as politically strident as her feminist sister of a generation later. But in their own way, they allowed Fuller to contribute important observations about women’s work in collage, to make technical breakthroughs and elevate her art to new aesthetic levels, and to inspire others to rethink the origins of collage.