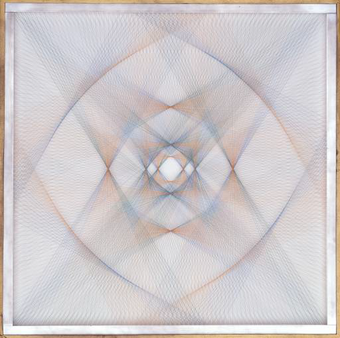

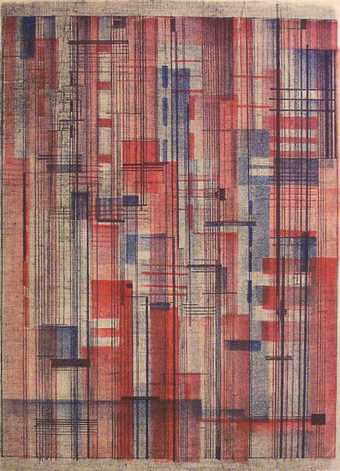

Fig.1

Sue Fuller

String Composition 128 1964

Plastic threads, wood, fabric and metal

914 x 914 x 38 mm

Tate T00757

© reserved

String Composition 128 (fig.1) weaves together multiple synthetic threads to create an intricate abstract pattern of intersecting diagonals. The threads radiate outward towards the edges of the frame, suspended like a flawless spider’s web against a white rayon background. The design achieves a mesmerising sense of depth, especially in the centre of the composition where the density of the intersecting filaments produces a kaleidoscopic effect, despite the shallow depth of its custom box frame. The gentle curves that seem to arc across each of the four corners of the work are an optical illusion produced by the densely overlapping straight lines of the threads that form parabolic sections. Fuller also embraced the chromatic illusions of her technique. As she explained in 1951, ‘where the different strings cross you get “free of charge” extra colors not really there except in the eye of the viewer’.1 As its vaporous trajectories of blue, green and orange overlap and blend, a jewel-like intensity of colour is achieved that belies the slight materiality of the work.

When Tate acquired String Composition 128 in 1965, another work by Fuller was then on display in The Responsive Eye exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, a landmark show that propelled the category of ‘op art’ into popular consciousness. However, as Frances Follin’s contribution to this study contends, Fuller’s work can be seen to lack the trademark impression of motion that characterised op art. Although Fuller’s association with the movement undoubtedly played a significant role in Tate’s acquisition of this work, it is now better understood in relation to her connections with a variety of key émigré painters and printmakers in post-war America, as well as a career-long commitment to the tenets of modernism and constructivism. Fuller’s use of thread can also be understood in relation to her study of craft and applied arts traditions.

Fuller was born in 1914 in Pittsburgh where she enrolled, in 1936, at the Carnegie Institute of Technology. While she was a student Fuller was awarded a prize for a watercolour painting depicting the workshop of an umbrella manufacturer, a subject that provides a suggestive precursor for the combination of systematised geometries and woven materiality in her later work.2 Fuller later recalled the early influence of modern artists whose work she saw at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie International in the 1930s.3 After a trip to Europe in 1937 she moved to New York to undertake a Masters degree at the Columbia University Teachers’ College. Over the next decade Fuller came into contact with many of the major teachers of American modernism. Before she enrolled at Carnegie, Fuller had already encountered Hans Hofmann while studying at the Thurn School of Art in Gloucester, Massachusetts; ‘the first giant I had contact with’, Fuller later recalled.4 In New York, she began attending the workshop of British-born printmaker Stanley William Hayter at the New School for Social Research in 1943, and soon after, enrolled in Josef Albers’s course ‘dealing with color and engineering problems’.5

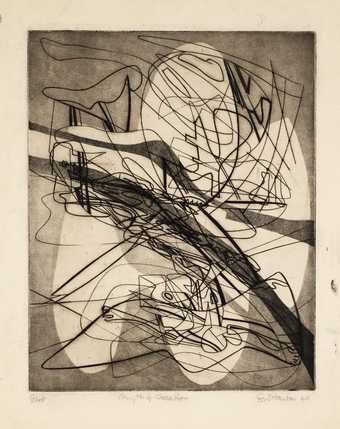

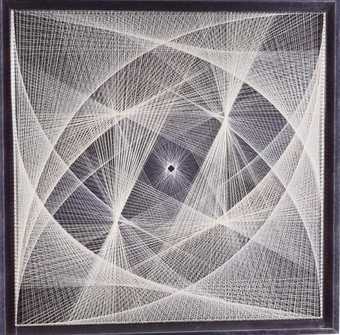

Fig.2

Sue Fuller

Tides of the City 1945

Soft-ground etching and colour stencil print

381 x 298 mm

Philadelphia Museum of Art

© Courtesy the Estate of Sue Fuller and the Susan Teller Gallery, New York

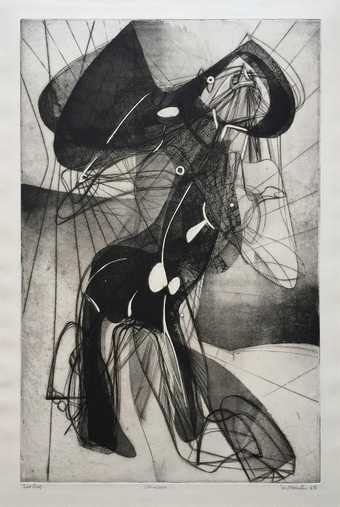

Fig.3

Stanley William Hayter

Myth of Creation 1940

Engraving, aquatint and etching on copper

251 x 200 mm

Tate P07027

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

Of the latter educators, it was Hayter’s influence that was most decisive, marking a period in Fuller’s development that provides the focus of the contribution to this project by Christina Weyl. Fuller had originally gone to Hayter’s Atelier 17 in order to learn jewellery engraving, but it was there that she began to produce the prints that secured her first art world successes.6 In lieu of paying tuition, Fuller served as Hayter’s studio assistant, which provided her with extensive direct experience of printmaking techniques and technologies.7 Her own early prints such as Tides of the City 1945 (fig.2) closely follow the example of Hayter’s works like Myth of Creation 1940 (fig.3), one of many abstractions whose biomorphic traceries suggest the body in motion. Fuller’s early prints were characterised by an enthusiasm for technical and material innovation and a 1947 exhibition lists prints on carved plaster among its works.8 According to another Atelier 17 printmaker, Fuller’s technical experiments extended to materials from the supermarket, experimenting with Karo brand corn syrup as a medium for ‘lift ground’ etching, a technique that she reportedly taught to the French surrealist André Masson.9

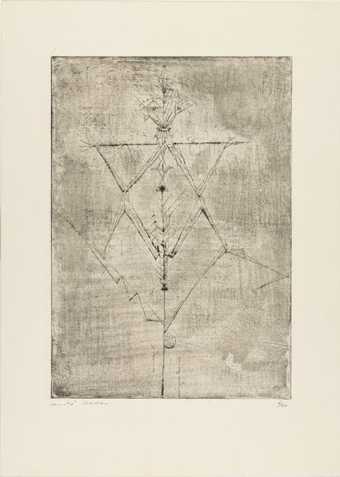

Fig.4

Stanley William Hayter

Amazon 1945–6

Engraving, soft-ground etching and scorper on plaster

625 x 402 mm

Source: https://www.gerrishfineart.com/hayter,-stanley-william-(1901-1988),-‘amazon’,-engraving,-soft-ground-etching-and-scorper,-1945.~2229

Fig.5

André Masson

Little Genius of Wheat 1942

Petit génie du blé

Etching and drypoint

353 x 247 mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Textiles of various sorts played a significant role in the printmaking techniques used at Hayter’s studio. Hayter himself used lace and thread for prints such as Amazon 1945–6 (fig.4), while Masson used burlap to provide the textured ground for Little Genius of Wheat 1942 (fig.5). Like Fuller, Anne Ryan and Louise Nevelson would both use lace in prints that they made at Hayter’s workshop.10 Nevelson’s use of lace and thread is especially pronounced in a print such as Majesty 1952–4 and art historian David Acton has noted the similarity of Nevelson’s technique to Fuller’s work.11 Across such prints, from the single thread and the grid, to the more complex decorative patterns of lace, fabric serves as a kind of readymade drawing, making it possible for linear forms to be simply arranged and combined to provide intricate and often multilayered pictorial effects.

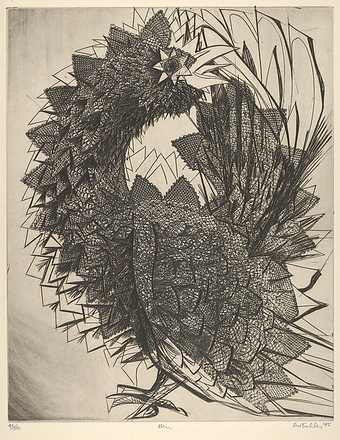

Fig.6

Sue Fuller

Hen 1945

Soft-ground etching and engraving

379 x 297 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Estate of Sue Fuller

In 1944 Fuller was included in the Museum of Modern Art exhibition Hayter and Studio: New Directions in Gravure, an exhibition through which curator James Johnson Sweeney characterised the work of Fuller and her peers as ‘research toward expanding the frontiers of expression’.12 Such scientific tropes, as will be shown, became central to Fuller’s artistic positioning. In 1947 she received the Louis Comfort Tiffany Fellowship and in 1949 a Guggenheim Fellowship. Fuller’s prints were first exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in 1949 as part of a survey of 250 American prints from the museum’s collection, and her widely exhibited print Hen 1945 (fig.6) was included in the print selection for Modern Art in the United States, shown at the Tate Gallery in 1956.13 As Weyl has shown, Fuller was among the key women printmakers who made Atelier 17 an international hub for printmakers, its expansive networks of exhibitions and associations buoyed by the mobility of the print medium itself.14

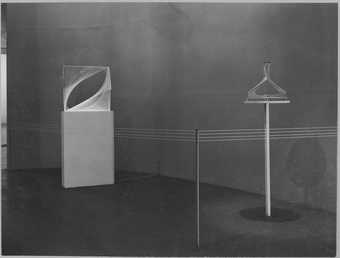

Fig.7

Installation shot of Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art New York, February–April 1948

Source: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3228?#installation-images

Fuller’s incorporation of textiles into her prints eventually led to stand-alone experiments with thread. ‘Their immobility became exasperating; so I pulled or stretched them, reassembled them; then finally reduced their structure down to one thread’, she later explained to critic Rosalind Browne.15 In the late 1940s such string compositions, produced initially for her prints, began to fill her studio, first taped to pieces of paper, later nailed to boards. Eventually Fuller came to understand these compositions as finished works in their own right. ‘They were so transparent!’ she remembered. ‘I’d just seen Gabo and Pevsner in the Museum of Modern Art and the sight of all that string overwhelmed me.’16 Here Fuller confirms the crucial influence of the 1948 joint retrospective of émigré artists Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner at the Museum of Modern Art on the development of her own string abstractions (fig.7).

Fig.8

Sue Fuller profiled in Life magazine, 31 October 1949, p.77

Source: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=KFIEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA77&dq=sue+fuller&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwifrJHrxJrVAhWsJMAKHYnpClsQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

In October 1949 a full-page portrait of the artist and her work in Life magazine further boosted the prominence of her technique (fig.8). Here she was photographed in the shadows of a dramatically lit space with a large string composition – a swooping design strung on a pegged wooden frame. The short text on her work emphasised that Fuller ‘exhibits in art galleries’ and that the artist ‘works hard over her composition and often dismantles a nearly finished job and starts all over’.17 The image furthered the suggestion of changeability by assembling balls of twine (or perhaps yarn) in a row, an ordinary material made extraordinary through the vision of the silhouette of the seated artist, posed in contemplation. As was the case for many American artists, the Life feature provided a powerful boon for Fuller’s profile. By 1951 an early string composition by Fuller was featured among the ‘pure geometric’ works in the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, and the following year, her String Composition 51 1953 was acquired by the Whitney Museum of American Art.18

Life magazine had identified the decorative possibilities of Fuller’s works, noting that they could be ‘hung on the wall or stood on the floor for partitions’.19 Throughout the 1950s Fuller’s string compositions came to be repeatedly positioned on the border between art and decoration. They were, as one journalist reported of a 1951 exhibition, ‘ultra-modern in a refreshing and delightful style’ and ‘an imaginative alternative to the ubiquitous mobile as a decoration for modern rooms’.20 The New York Times magazine illustrated Fuller’s work in a spread on modern interior décor in 1953.21 Exhibition contexts also emphasised such decorative possibilities: a 1950 show at the Bertha Schaeffer Gallery in New York saw her string compositions displayed alongside ceramics by British potter Bernard Leach, while a 1956 display at the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, New Hampshire, saw her work shown alongside tapestries by Anni Albers.22 As Fuller absorbed the lessons of techniques ranging from lacemaking and glassmaking to calligraphy, the so-called decorative arts provided valuable sources for her practice, aesthetic and material references assimilated within her resolutely avant-garde commitments.

As Christina Weyl’s essay in this study explores in greater detail, accounts of Fuller’s work have routinely understood it through the prism of her gender, drawing on the feminine associations of the textile medium. Critic Stuart Preston, writing in 1950, thought that Fuller’s string constructions demonstrated that ‘even a purely feminine and ingenious talent can catch a hold in the solemnities of constructivism’.23 Even apart from the light and lively character of works by Gabo and Pevsner, Fuller’s classification as the ‘lighter moment’ of geometrical abstraction relied on the suggestive links to the ‘women’s work’ of weaving, connections that the closely related forms of artists such as Richard Lippold and Kenneth Snelson avoided as much by their gender as by their use of wire rather than string.24 In their 1981 essay ‘Crafty Women and the Hierarchy of the Arts’, art historians Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock explain how an ‘association with the traditions and practices of needlework and domestic art can be dangerous for an artist, especially when that artist is a woman’.25 As feminist artists and critics of the 1970s and 1980s began to unpick the ideological assumptions of such hierarchies, Fuller’s achievements as a woman artist began to attract new attention. Fuller was, however, sceptical about her revival within this milieu, claiming that she was ‘the “token” artist in all the museums they picket’, continuing:

it took work to even be a ‘token’ and they shouldn’t kick about it. I was born liberated before there was Women’s lib … I was way ahead of my time! They can call me token if they like, but there weren’t many others around doing what I did then.26

Fuller evidently kept abreast of developments in feminist art history and her letters to her friend Florence Forst held in the collection of the Archives of American Art make reference to the writing of key feminist art historians such as Linda Nochlin and Cindy Nemser. But Fuller was careful to differentiate her own politics from this field. ‘I guess I’m a drop-out from the usual art politics – hence unknown in these circles’, she explained in one such letter from 1978. In her private correspondence Fuller did not hesitate to distinguish her art from her more overtly political contemporaries, especially those who did not share her commitment to abstraction. ‘I felt even then that Isabel Bishop … was really not part of what I considered the major direction of 20th Cent. Art’ she wrote. ‘Alice Neel is another Philip Evergood whose painting I could never stand and whose politics less. Minna Citron seemed to be a chameleon running hard after whatever she considered the latest trend to be … Rather it is Agnes Martin, Perle Fine … [artists] more involved in Bauhaus fundamentals, I prefer.’27

Fuller equally rejected the philosophical ruminations that characterised the statements of many artists of the post-war decades. ‘No philosophical creeds, no re-writing of the sermon-on-the-mount in his own words’, she demands in one letter.28 Fuller’s modernism was, instead, persistently affirmative:

I have always admired what engineers do – the space age is my meat – and not monsters and glop of science fiction – but the real inquiries which succeed – in expanding the mind of a parochial-inclined humanity. Limitations delimited – that’s what I like. They always said it couldn’t be done – so do it and open up world upon worlds of new knowledge from which to search out better ways and meaning to the human experience. That’s why I like Arthur Clarke as a science fiction writer – He’s reasonable and what he indicates is fantasy may actually one day be realized … My business is to know what I believe, do what I see, and listen to what is really important – those observations (usually scientific) which portend great things for mankind – and to be done with the dust of ages.29

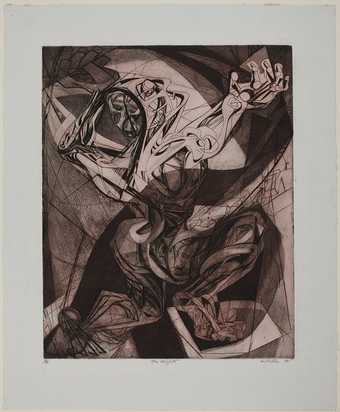

Fig.9

Sue Fuller

The Heights 1945

Engraving and soft-ground etching on white wove paper

375 x 302 mm

Art Institute of Chicago

© Estate of Sue Fuller

Such faith in science and technology stood in stark contrast to the dark atomic-age anxieties through which post-war American painting and sculpture assimilated the influence of surrealism. Fuller ridiculed what she dubbed the ‘Ouija-Board artist’, who entertained ‘mysticism, witchcraft and god-knows-what’.30 It is worth noting, however, that Fuller’s early contact with émigré surrealists at Hayter’s studio did leave its mark on her work of this period, as can be seen in a print such as The Heights 1945 (fig.9).31 But as Fuller came to align her art with the values of clarity and precision, she came to dismiss a taste for the ‘macabre’ as a return to the ‘middle ages’ – an age of ‘darkness and superstition’.32

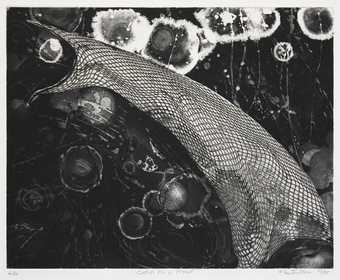

Fig.10

Sue Fuller

Catch Me A Planet 1952

Soft-ground etching and aquatint on white wove paper

295 x 371 mm

Source: https://www.annexgalleries.com/inventory/detail/15358/Sue-Fuller/Catch-Me-a-Planet

Two of Fuller’s prints from the 1950s help make explicit the scientific resonances of her swooping, gridded geometries, so redolent of mathematic graphs and charts. With their explicit reference to the dream of space exploration, Catch Me A Planet 1952 (fig.10) and Ladle for the Moon 1952 both capture Fuller’s persistent wonder at the new perspectives on the world made possible by science.33 ‘The path of a trajectory to the moon or in orbit around Mars is a line drawing’, she later noted, describing how her own ‘linear geometric progressions’ equally engaged with the ‘visual poetry of infinity in the space age’.34 These were values recognised by critics too. In 1951 a writer thought one of works looked like ‘the architectural design for a flying saucer’, while a 1960 exhibition of string compositions prompted one critic to reach for comparisons to ‘rockets, skywriting or jets shooting across the sky’.35

Fig.11

Sue Fuller

New York, New York! 1950

Lithograph

533 x 406 mm

© Courtesy the Estate of Sue Fuller and the Susan Teller Gallery, New York

Source: http://www.susantellergallery.com/cgi/STG_work.pl?artist=fuller&img=26&nam=SUE%20FULLER

Another print from the same group of works titled Fabulous City 1952 also suggests the distinctly urban perception of gridded streets and reflective glass that underlies the intersecting lines of her purely abstract compositions. In 1954 Fuller wrote that she was ‘inspired by the engineering genius of our times and civilization, expressed in transparency, light and balance’.36 These enthusiasms are no less evident in her string compositions than in her prints, making the abstract rhythms of the city their subject, such as New York, New York! 1950 (fig.11). Critic David Shirey thought that they resembled ‘prisms, giant crystals, snowflakes in suspension or the criss-crossing of telephone wires or cables on cantilever bridges’.37 Fuller’s father was a construction engineer and one biographical reading of her work hints that the model suspension bridges he assembled might have spurred her own designs.38

The firmly social resonances that Fuller established for her abstractions were commitments that she first articulated in a January 1943 article exploring the value of the art teacher in a time of war.39 Here Fuller addresses the mounting perception of art as an unnecessary luxury, and even admits her own patriotic desire for ‘an identification badge and a riveting machine’.40 But she also goes on to argue for the value of art to the war effort, suggesting that students might learn about perspective by drawing ‘tanks and planes and ships’, make objects from scrap and other ‘non-priorities materials’, study ‘camouflage theory’, or ‘uniforms and insignia’, or the ‘intricacies of interlingual communication’ through the bulletins from the Office of War Information.41 Alongside such practical concerns Fuller further emphasises art’s more profound contribution to the identity of war-time America and its place in the world:

At a time when tensions in the world and at home are adding their burden to the characteristic emotional problems of the adolescent, is it wise to deny the child his one chance to salvation … To leave the next generation without experience in the constructive elements of art which are ever a work over and above the barriers of nationality, language and politics, is to leave them without understanding of the harmony of living … At a time when resignation, futility, and despair threaten to engulf the individual, should we deny the Freedom of Expression.42

Fuller’s sensitivity to such issues was undoubtedly sharpened by her visit to the infamous Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich in 1937, where she encountered the broadest gamut of European cubism, expressionism, dada, surrealism and constructivism, presented within a propagandist framework that must have left an indelible impression on the young artist’s understanding of the political stakes of modern art.43

Some decades later, Fuller was unexpectedly entangled in Cold War politics during the visit of Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov to the United States. After attending meetings at the United Nations in June 1955, Molotov was taken to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a tour of its collection. The press tailed Molotov and his delegation, attentive to matters that might speak to the cultural divide between the United States and the Soviet Union and the Cold War cultural conflicts this gulf epitomised. The tour, which lasted for one hour and ten minutes, ranged across the museum’s collection from the fifteenth century onwards, ending in the museum’s American galleries. Curator Robert Hale presented works by Loren McIver, Morris Graves, Edwin Dickinson, Georgia O’Keefe, Stuart Davis, Bradley Walker Tomlin and others to the Soviet diplomat, but it was a string construction by Fuller that most dramatically prompted Molotov’s ‘dumbfoundness at contemporary American abstractions’:

The work that seemed to baffle Mr Molotov most was Sue Fuller’s ‘String Composition 50’, a somewhat geometric work vaguely resembling the lines on a barograph. ‘What does it mean?’ asked Mr Molotov in a puzzled voice. ‘It is the artist’s abstract conception’, replied Mr Rousseau. Mr Molotov pondered the answer for a moment. Then he went up for a closer look. ‘How is it made?’ he asked. When told it was made from strings, he looked a moment longer then moved away, lightly shaking his head.44

This was front-page news and in the following days the New York Times followed up with an illustrated comparison between Fuller’s String Composition 50 and a portrait of Elizabeth Farren by the British Regency painter Thomas Lawrence, which Molotov had particularly admired.45 For the most part Fuller avoided political alignments, but one suspects she would have approved of the dramatisation between realism and abstraction that the comparison suggested, casting her art as the adversary of Soviet cultural conservatism. Perhaps it was the knowledge of this confrontational comparison that encouraged the United States Information Service to include Fuller in their 1961 exhibit Plastics USA, for which American commercial and creative innovations in plastic were toured to Kiev, Moscow and Tbilisi, attracting more than 375,000 visitors.46

Fig.12

Dame Barbara Hepworth

Stringed Figure (Curlew), Version II 1956, edition 1959

Brass and string on wood base

514 x 768 x 432 mm

Tate T03137

© Bowness

As her early string compositions from the mid-1940s began to warp and sag, Fuller came to favour synthetic materials for their promised permanency. An archival photograph of one early composition notes that its string had ‘deteriorated’, and that this work was ‘the first in a succession of filaments tried before she [Fuller] settled on nylon filament’.47 The stability of her work was of prime concern. ‘If your work is going to be found in a museum’, she told critic Rosalind Browne, ‘then the museum should have the guarantee that you’ve done your best to make it permanent’.48 For Fuller, such responsibilities were closely connected to the obligation of the artist to ‘record your time’, such that material innovation might provide a persistent record of the new. This was expertise that Fuller occasionally applied to other artworks. In the 1970s, for instance, collector Lew Wasserman enlisted her help to repair the degraded string in a Barbara Hepworth sculpture Stringed Figure (Curlew) 1956 (fig.12), a project for which she liaised with the Barbara Hepworth Museum to source the correct twine for the work.49

Fuller had first encountered synthetic thread at a hardware store where she recalled seeing a window screen made from the new material in the mid-1950s.50 Her move from hand-painted and textured fabric backings and twine to the slicker finish of aluminium frames and synthetic thread conforms with widespread artistic tastes for industrial aesthetics in the 1960s. This extended to an optimistic perspective on the possibilities of artistic patronage from industry. ‘Industry has been backing artists and letting them do their own thing. It’s one of the solutions for art today’, she told an interviewer in 1972.51 In line with such views, Fuller repeatedly listed the brand names of her materials, such as Teflon and Lucite, favouring such proprietary designations over more generic material names. Of String Composition 128, Fuller informed Tate that it was glazed with Rohm and Haas Plexiglas, and advised that its polypropylene thread had been ‘tested by [the] Mellon Institute, Pittsburgh [with] 500 hours in the fadeometer’.52

Corporate clientele constituted an important market for Fuller’s string compositions from the outset. Her String Composition 1 1946 was purchased by the Celanese Corporation of America and her 1951 exhibition at the Corcoran Museum of Art included a total of five early string compositions listed in this same corporate collection.53 Not only did Celanese manufacture synthetic yarns such as the Fortisan brand, but their corporate advertising often made reference to modern art and it seems possible that Fuller’s works served some promotional function for the company and the materials it manufactured. Prominent private collectors such as Larry Aldrich, Stanley Marcus and Philip Johnson all purchased works by Fuller at the Bertha Schaeffer Gallery exhibition in 1965. String Composition 336, bought by Johnson, was subsequently donated to the Museum of Modern Art.54

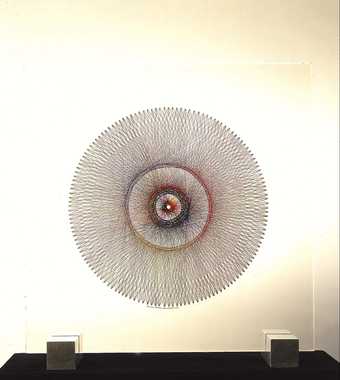

Fig.13

Sue Fuller

String Composition T-220 1965

Nylon and Teflon tubing

1067 x 1067 mm

McNay Art Museum, San Antonio

© Estate of Sue Fuller

The collector Emerson Crocker, who owned several of Fuller’s works, provided the funds for Tate’s acquisition of String Composition 128. Crocker also donated the dense and more complicated monochrome String Composition T-220 1965 (fig.13) to the McNay Art Institute, San Antonio, in 1965, where it was included in Fuller’s major solo exhibition there the following year. Many of the works in the McNay exhibition could be viewed from both sides, including the freestanding String Composition 530 1965.55 Tate director Norman Reid had also ‘admired the plastic embedments, but after taking into consideration the condition of the walls at Millbank, elected to select a non-see-through medium as his choice’.56

Fig.14

Sue Fuller

String Composition W-253 1984

Mahogany, brass and cord

3658 x 4267 x 4267 mm

McNay Art Museum, San Antonio

© Estate of Sue Fuller

Fig.15

Sue Fuller

String Composition 534 1965

String embedded in Lucite, mounted on two metal bases

553 x 534 x 254 mm

Smithsonian American Art Museum

© Estate of Sue Fuller

An inventory of Fuller’s work from the 1970s indicates that the numbering of her works was not simply chronological, but also served to categorise their mode of fabrication. Compositions titled 1 to 199 are ‘string compositions on pegged frames with cloth tacking present’ and an ‘aluminum frame set in brass frame’. Series 200 works are strung on both sides with transparent Plexiglas glazing, designed to be – as Fuller explained elsewhere – ‘hung from ceiling out from wall’.57 String Composition W-253 1984 (fig.14), a later and more three-dimensional example from this number range, is held in the McNay Art Institute. Series 300 works are the string compositions embedded within Lucite plastic objects. Series 400 works are string composition cubes – with 400–449 indicating works with a flat shape, while 450–499 designating more three-dimensional shapes. String Composition 534 1965 (fig.15), in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, for example, is a circular-shaped composition embedded in Lucite. Such designations continue until series 900 works, used by the artist to indicate special commissions. Fuller’s means of categorising work overlaid the conventional numbering of artistic series with a more classificatory, even corporatised system – more like unique identifiers in a product catalogue than a simple chronological series.58

Fuller’s titling convention also suggests her cross-media reference to music as a model for abstraction. As one critic described in 1967, ‘there is music in her work … a pulsating, vibrant tempo that a viewer almost can feel in his bones’. Such qualities provide further resonance with Fuller’s choice of the term ‘string composition’. Fuller’s compositions were, according to the same critic, ‘musical in their execution – the orderliness and intricate detail are as balanced as a baroque fugue and as complete as a Mozart symphony’.59 Emphasising the ‘rhythmic stress and strain’ of Fuller’s string compositions, Emerson Crocker praised their ‘visual harmonies’.60 Fuller occasionally encouraged such metaphors for her works, once describing them as deploying ‘contrapuntal’ patterns or exploring ‘variations on a theme’.61 The frames of her compositions were, from this viewpoint, ‘the instruments’, while the overlapping threads produced a ‘symphony of visual harmonies’.62

Fig.16

John D. Schiff

Installation view of First Papers of Surrealism exhibition, showing Marcel Duchamp’s His Twine 1942

Gelatin silver print

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Fig.17

Installation shot of Airways to Peace exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art New York, July–October 1943

Source: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3138?locale=en#installation-images

Fuller’s experimentation with transparency further prompted some viewers to contemplate the capacity for her art to dissolve the borders between the art object and the viewer. ‘Normally visitors in a gallery do not expect to literally bump into the art itself. A display made up entirely of Miss Fuller’s transparent compositions would resemble a labyrinth of strings’, imagined one critic in 1961.63 If such a description alludes to Fuller’s relation to the webs of Marcel Duchamp’s chaotic stringed installation for the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition in Manhattan in 1942 (fig.16) or Herbert Bayer’s ‘tension lines’ of string that intersected the Airways to Peace exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1943 (fig.17), they can equally be understood to preempt the sculptural installations of fibre artists such as Lenore Tawney, Kazuko Miyamoto and Kay Sekimachi. While the use of thread in 1960s and 1970s art tended towards natural textures and informal off-loom techniques, Fuller’s more controlled approach was also exhibited alongside the process-oriented work of artists such as Robert Morris, Eva Hesse and Alan Sarat in the Sidney Janis Gallery’s 1969 String and Rope exhibition.64

For all of Fuller’s interest in artistic practices outside the limits of fine art, her objects also transgressed more entrenched divisions for the modern artist. Early in her career it was reported that Fuller struggled to gain admission into art shows ‘because they have no classification for her work’.65 As the critic Dorothy Adlow described in 1961, Fuller’s practice combined the ‘features of a drawing, a textile and a construction’.66 Fuller was aware that her art occupied a liminal position, linear in orientation, but hung on a wall and almost as tactile as it is visual in its sensory effects. A string, Fuller explained, can ‘draw on itself’, without the need for a support, and further, ‘its intersections become three dimensional’.67 Relying as they do on the three-dimensional surface of the intaglio matrix, Fuller’s progression from printmaking to string composition realises the shallow relief inherent to such processes in the final form of her works. It is little wonder that the majority of research on Fuller has come from scholars of printmaking. While building on such approaches, this project uses String Composition 128 to stage the first extended investigation of Fuller’s mature practice, examining the varied artistic and cultural resonances of her ambitious reliefs.