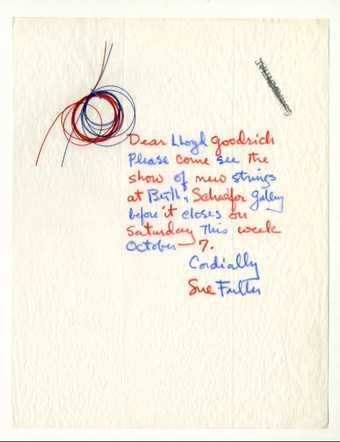

Fig.1

Sue Fuller

Handwritten letter to Lloyd Goodrich, 1961

Frances Mulhall Achilles Library and Archives, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Source: http://dcmny.org/islandora/object/artistscorrespond%3A1393

In 1961 Sue Fuller wrote a letter to Whitney Museum of American Art curator Lloyd Goodrich, inviting him to her exhibition of ‘new strings’.1 The content of her note is unremarkable, but the form it takes is rich with associations. Attached to the top left-hand corner of the letter are loops of blue and red thread (fig.1). Their form and colour are echoed in the looping, blinking cursive of her text below. With its off-centre layout and generous white space, Fuller’s note declares the up-to-date modernism of its maker, absorbing even the most rudimentary of communications into her artistic output. The loops of thread are offset so as to suggest the three-dimensional illusions of stereoscopic imagery – alluding, perhaps, to Fuller’s own ambiguously spatial practice. The attached threads also evoke a lock of hair from a Victorian love letter, updating this sentimentally personal gesture for a new age of synthetic fibres.

As is so clear from this source, string and thread were central to Fuller’s artistic identity. These were materials whose rich cultural associations and histories had taken her, as she put it, ‘from the waterfront up to the Empire State Building – from fisherman to research chemists’.2 But they were also interests that saw her approach reach beyond the conventional modernist preoccupations for newness suggested by her choice of synthetic monofilament, a material more commonly used as fishing line. Fuller’s immaculate studio might have taken on the appearance of a laboratory – according to one visitor, with ‘piles of carefully, stacked, neatly annotated and pasted records of thread and color tests’ – but it was also peppered with ‘samples of her own handmade lace’ and other fibres of a less high-tech variety.3

Fig.2

Sue Fuller

Handwritten poem ‘String Composition #128’, 30 November 1965

Tate Artist Catalogue File XXXX

This essay will recover Fuller’s wide-ranging ‘exploration of the materials and methods’ involving thread, including string figures, knotting and lacemaking, returning to the sources she encountered in order to reflect on the social and cultural resonances of her practice.4 Tate’s archives contain another carefully crafted missive from Fuller that points to specific sources for her interest in one of these material cultures. Asked by the museum to explain String Composition 128, Fuller chose to compose a poem (fig.2). Her handwritten verse concludes with two distinctly unpoetic citations concerning the history of ‘string figures’ such as the children’s game of cat’s cradle. The poem ends as follows: ‘cf Kathleen Haddon Cambridge’ and on the following line, ‘W.W. Rouse Ball Oxford’. Haddon and Rouse Ball were leading scholars of the history of string figures in the early twentieth century and Fuller’s familiarity with their research confirms her engagement with this once ubiquitous form – a tradition that was, until the end of the nineteenth century, probably the most widely played game in the world.5

Connections between Fuller’s art and the cat’s cradle were a persistent trope in accounts of her practice. A photograph for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 1955 shows Fuller manipulating a taut matrix of string between her hands as she plays the game. As the newspaper declared, Fuller was ‘the Pittsburgher who took the “cat’s cradle” game … and, with the magic of talent, pioneered in lifting its old designs to a new expression in modern art’.6 Faced with the challenges of capturing Fuller’s vaporous abstractions, an enterprising photographer perhaps suggested the pose, a shot that would perhaps provide the human-interest angle that her artworks lacked. It was not the first time that a reporter had suggested the connection; as early as 1949 the New York Times noted that ‘the cat’s cradle acquires aesthetic rank’ in Fuller’s art.7 Far from just a publicity tactic, however, Fuller’s serious engagement with the history of the cat’s cradle indicates that the form was a fundamental prototype for her art.

Fuller found her copy of Kathleen Haddon’s Artists in String: String Figures; Their Regional Distribution and Social Significance of 1930 in a second-hand bookstore. ‘Within its hundred and forty-nine pages was a careful documentation of drawing in string evolved by peoples of all nationalities, cultures and times’, Fuller recalled of the discovery.8 Haddon’s book itself suggests the sheer imaginative leaps that string figures demanded: within just a few pages, for instance, two seemingly similar crisscrossed rectangles are identified as, on the one hand, ‘Four Men Going to Make a Garden’ and on the other hand ‘Little Pigs Followed by Their Mother’.9 Fuller’s 1954 article in Craft Horizons presents her abstractions alongside three traditional cat’s cradles depicting a ‘turtle’, a ‘tepee’ and a ‘man climbing a palm tree’. The sheer distance of these geometric shapes from the subjects they represent confirms the human capacity for what Fuller characterised as ‘abstract symbolic’ image making, imaginative leaps that her own abstractions might themselves produce.10

Fuller was aware of the storytelling traditions associated with string figures. For a 1951 profile piece the artist explained that her method ‘goes back to primitive peoples who wound strings around their fingers in various symbolic forms to illustrate the stories they told’.11 Haddon’s book provided Fuller’s typically modernist adoption of the ‘primitive’ string figure with evocative details concerning the social bonds encoded in its materiality. ‘Pull out a piece of string … the effect is magical … shyness is forgotten: each vies with each in showing new figures’, Haddon explains. ‘There are few memories more delightful than those chance encounters with parties of natives – the squatting beside the track, the exchange of courtesies in string, the mutual delight in recognizing old favourites, the excitement and applause that great new ones … and all without one word being spoken on either side.’12 Besides the cross-cultural misrecognitions that we might now know such transmissions to have entailed, Fuller’s engagement with the cat’s cradle furthered her ambitions for a universal language of abstraction – as she put it elsewhere, an art of ‘interlingual communication’.13

The second scholar of string figures that Fuller names in her poem is William Rouse Ball, an Oxford mathematician and amateur magician. His 1920 book An Introduction to String Figures developed from a lecture he gave on the subject at the Royal Institution in London. Given his interest in magic tricks, Rouse Ball’s book was especially attentive to the performative aspects of the string figure and the extent to which speed and dexterity added to its effect. This was especially important for ‘string paradoxes’, as Rouse Ball terms them, in which the ‘final result appears suddenly, almost dramatically’.14 He describes how other designs unfold more gradually to accompany the narrative of a storyteller. One British form, for instance, enacts ‘the misadventures of a thief who stole some tallow candles’, while an indigenous Australian pattern serves to animate ‘a man climbing a tree’.15

Such possibilities caught Fuller’s attention. In her 1954 article she distinguishes between string figures that represent ‘static pictures’ from those ‘whose first symbol dissolved into another, with the movement of a finger or two’.16 Following Rouse Ball, Fuller also noted that the string figure tradition included ‘trick pictures whose sudden transformation on the fingers of an artist-storyteller could only end with his audience dissolved in laughter’.17 Haddon went so far as to nominate the string figure as ‘the first embodiment of the cinema – the original moving picture’.18 Such effects acquire particular relevance as Fuller’s art was absorbed into the field of optical art, but the emphasis on the hands of the artist is also noteworthy. Haddon describes, for instance, how string figures involve a ‘muscular memory that is partly unconscious’.19 Rouse Ball’s text emphasises the ‘digital skill’ of making string figures, to similar ends.20 In these terms, Fuller’s compositions register the manual dexterity involved in their creation. Like an origami construction whose form embodies the complex actions of its folding, Fuller’s string compositions appear as records of their making, their shifting perceptual effects providing traces of the skilled handiwork of their production.

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Stringed Figure 1938, cast 1960

Bronze and elastic string

273 x 343 x 197 mm

Tate T00386

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Fabre de Langrange

Surface string model of conoid in contact with a hyperbolic paraboloid 1872

Brass, cotton, lead and wood

Science Museum, London

© The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

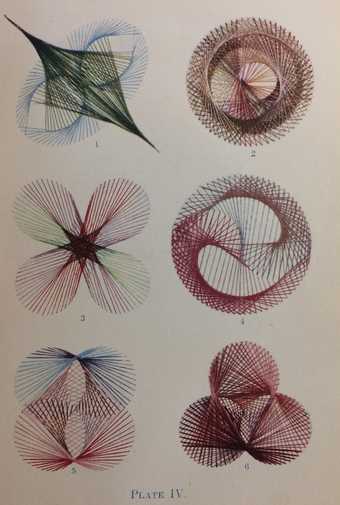

Fig.5

Illustrations from Edith Somerville, A Rhythmic Approach to Mathematics, London 1906

Despite Rouse Ball’s own mathematical interests, Fuller’s interest in his work differs from more typical interests in geometrical forms in thread. The stringed figures of Henry Moore, such as his Stringed Figure 1938 (fig.3), are known to have been informed by the mathematical models of Fabre de Lagrange (fig.4), which the artist saw at London’s Natural History Museum.21 Later forms of ‘string art’ frequently cite the influence of the ‘curve stitching’ of nineteenth-century mathematician Mary Everest Boole, whose techniques embroidered coloured thread through ‘sewing cards’ to form curves, spirals and other geometric forms.22 Boole’s technique was further popularised in Edith Somerville’s 1906 publication A Rhythmic Approach to Mathematics, which was illustrated with complex string compositions designed to help teach mathematical equations (fig.5). Somerville’s example is also cited by art historians Martin Hammer and Christina Lodder in relation to the work of Naum Gabo and Barbara Hepworth, and while Fuller’s use of string was certainly influenced by the techniques of these artists, it is significant that her own interests tended towards more commonplace uses of thread and string.23

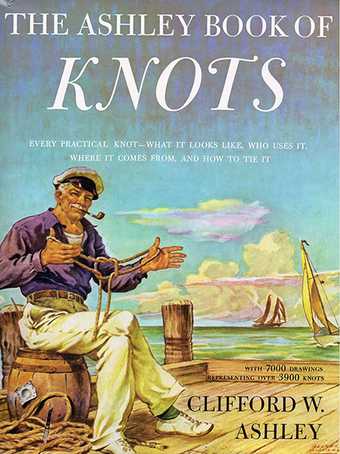

Fig.6

Cover of Clifford W. Ashley, The Ashley Book of Knots, New York 1944

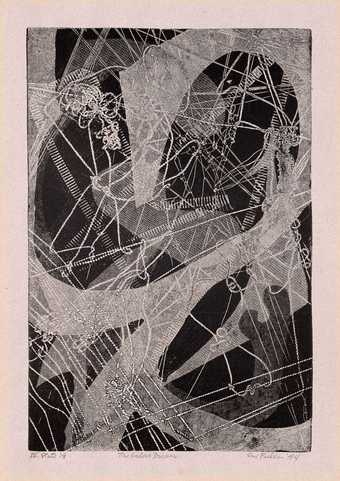

Fig.7

Sue Fuller

The Sailor’s Dream 1944

Soft-ground etching printed in relief

226 x 151 mm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© Estate of Sue Fuller and the Susan Teller Gallery, New York

Knotting was one such quotidian tradition upon which Fuller drew. Here she turned to the work of Clifford W. Ashley, whose monumental The Ashley Book of Knot was first published in 1944.24 Illustrated with an estimated 7,000 drawings of knots by Ashley, an artist and sailor, as well as a writer, the book became the standard reference text for the subject of knot tying. The cover of the first edition of Ashley’s text (fig.6) usefully suggests the material knowledge shared between the art of knots and the hobby of cat’s cradles, an association that complicates the presumed femininity of Fuller’s practice. In 1951 Fuller described this book as ‘a great treasure’.25 Ashley refers to both Haddon and Rouse Ball in his short bibliography of ‘practices allied to knotting’, and it may indeed have been these citations that prompted Fuller’s further investigations into their work.26 Fuller’s tumultuous print The Sailor’s Dream 1944 (fig.7) suggests an especially direct reference to Ashley’s landmark text, and the work is illustrated in the article in which she recounts her discovery of the book.

Just as historians of string figures sought to preserve forms they assumed to be ‘disappearing’ by recording them, so too was Ashley’s book concerned with the preservation of knots. The aesthetic and material pleasures of the form prompt some of Ashley’s most evocative prose:

the simple act of tying a knot is an adventure in unlimited space. A bit of string affords a dimensional latitude that is unique among the entities. For an uncomplicated strand is a palpable object that, for all practical purposes, possesses one dimension only. If we move a single strand in a place, interlacing it at will, actual objects of beauty and utility can result in what is practically two dimensions; and if we choose to direct our strand out of this one place, another dimension is added which provides opportunity for an excursion that is limited only by the scope of our own imagery and the length of the ropemaker’s coil. What can be more wonderful than that?27

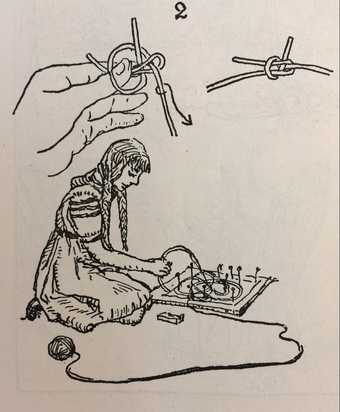

Fig.8

Illustration from Clifford W. Ashley, The Ashley Book of Knots, New York 1944

The page facing this passage features an illustration of a girl sitting on the floor arranging a ball of yarn or thread onto a pinned backboard, perhaps using a technique related to macramé, but equally suggesting the processes that would become central to Fuller’s art (fig.8).28 Elsewhere in the book Ashley describes armatures with pins and pegs including braiding spools and complex patterns of netting and rigging that equally require fixed armatures.29 Such sources offer possible prototypes for Fuller’s own technique of threaded frames. But even apart from the value of Ashley’s text as a practical source for techniques, his vivid account of the visual and sensory gratifications of rope resonated for Fuller as she explored the possibilities of an art made from string.

Fig.9

Sue Fuller

Cacophony 1944

Etching and aquatint

302 x 223 mm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

© Estate of Sue Fuller

Fuller’s interest in lacemaking was equally attentive to the technical development of this medium. ‘In the nineties there was a vogue for making Arabian lace’, Fuller explained. ‘A printed pattern was supplied and a manufactured edging was available to outline the major divisions of the design. All the needlework of wheels and ladder fancywork in the subdivisions was to be worked by hand.’30 Finding one such piece of lace among her mother’s belongings, Fuller incorporated the needlework into her printmaking technique, before seeking other textiles to use to make prints, and eventually making her own ‘compositions in thread’.31 While many of her prints made use of textiles, the printed pattern of lace fragments is especially visible in her luridly coloured Woman with Bird 1947. In other instances, Fuller experimented with everyday examples of string: Cacophany 1944 (fig.9) was made, according to Mary Maloney-Rose, from an old woven bag for garlic.32

Fuller is known to have engaged with lace expert Marian Powys Grey who had run a lace store in New York and who went on to advise the Metropolitan Museum of Art on their lace collection.33 Powys Grey was the author of Lace and Lacemaking, published in 1953, and was close enough to Fuller to present her with a volume from her personal collection of samples documenting the history of lace.34 Powys Grey’s hope for a modern revival of lacemaking offers particular relevance to Fuller’s practice. ‘If the art of lace is to hold its high place it must submit to the process of evolution and express in new and original forms the spirit of our own age.’35 In arguing for the aesthetic merits of lace with ‘clean lines’ and a ‘fine sense of fitness and economy’, Powys Grey warned against literary content, arguing that such features overshadow ‘the intrinsic beauty of lace as a work of art’.36 Ignoring modernist aversions to decoration, Powys Grey imagined the possibilities for lacemaking techniques to be adapted to contemporary architecture and design:

Lace, an ornamental openwork wrought of fine threads, is very much in the spirit of our own age … Lace has that transparent quality that glass and aluminum give to new buildings. The modern interior designer’s emphasis on lightness and transparency and his frequent use of sheer hangings as partitions indicates he would be happy to seize on the medium of lace-makers and manufacturers would modernize their patterns making them to harmonize with the spirit of our own age. Designs for lace in the modern world must be in the modern mood.37

Powys Grey does not mention Fuller, and it is not known if they were in contact when this was written, but her imagining of a new modernist lacemaking tradition is redolent of Fuller’s emerging practice:

That lace has a strong affinity for modern art and design may be seen in the work of some of our best modern artists. In looking at the pictures in the new galleries the lace-maker is tempted again and again to translate the painting into thread. The lines of the drawing removed from the flat surface would become alive and flexible and achieve a body capable of making a shadow … If the artists would work with the lace-people there would be a great revival, and a new life, a new outlook, would come to the lace industries.38

Across all of the material cultures with which Fuller engaged, the desire to preserve pre-industrial traditions is a persistent thread. Fuller is known to have communicated with Margaret Brooke, the author of Lace In the Making, published in 1925.39 She was also in contact with Elisha Dyer from the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration (now the Cooper Hewitt, the Smithsonian’s design museum).40 Fuller’s evident interest in the techniques of antique lace absorbed, I think, the desire of lace collectors and scholars to preserve and protect the history of this medium.

Fuller’s approach to colour also looked towards textiles as a model. ‘We have all marveled at the beauty of a color woven in a Scottish plaid’, she writes, and its ability to effect ‘many shades and hues’ by ‘the juxtaposition of a few constant color skeins’.41 In observing that tartans achieved their striking ‘mixture of color … in the eye of the beholder’, Fuller connected the chromatic effects of such textiles to modernist interests in the perceptual effects of colour – a history that must have been reinforced by her studies with Josef Albers.42 Fuller notes, for instance, that it was Anni Albers who introduced her to ‘the achievements of the Coptic and Peruvian weavers’.43 Albers’s interest in the capacity for woven textiles to produce ‘slight optical vibration of intersecting raised and lowered threads – shiny and dull, lighter and darker … quiet yet alive, responsive to lighting’, provides formal terms that vividly describe the effects that Fuller achieves.44 Like Anni Albers, Fuller’s approach to abstraction manages to cross the borders between art and craft that modernism more often sought to regulate.

Fuller’s valuation of such material cultures as ‘arts worthy of study’ preempts the reorientation of post-war fibre art towards the quotidian, a shift that art historian and curator Elissa Auther has described elsewhere.45 The significance of resuscitating a neglected medium was of explicit interest to Fuller. ‘By laying aside a good many misconceptions about what constituted art, my thought expanded to include appreciation for not only mediums I had heretofore overlooked’, she explained. ‘To me the most important part of this whole development’, Fuller writes, ‘lies in the realization that art has always belonged to all peoples of all times and includes all mediums’.46 String was, for Fuller, that common thread. As she wrote, her focus on this material alone ‘opened my eyes to see and appreciate that which mankind has already accomplished in related fields’.47 In validating diverse material cultures from a range of periods and places, Fuller’s string compositions declared a modernism that openly admitted the value of craft and the handmade in its constitution, one that, for all of its unequivocal abstraction, remained engaged in traditions of the past and of the everyday.