Fig.1

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum 1991–6

Glass, 50 cardboard boxes, paper, video, slide, light bulbs and other materials

Displayed: 2200 x 10000 x 600 mm

Tate T07438

© Susan Hiller

Photo © Tate

Since Sigmund Freud’s brief but much discussed correspondence with surrealist writer André Breton in 1932–3,1 the relationship between art and psychoanalysis has been plagued by mutual incomprehension and suspicion, with a few notable exceptions.2 Freud feigned the modesty of the amateur in his writings on art and literature, which are among his most criticised but also most widely and passionately debated, especially ‘The “Uncanny”’ (1919).3 Psychoanalytically informed scholarship in art history, theory, and visual and media culture proceeds not on the basis of Freud’s ideas about art but almost despite them, body-swerving them more often than not, in favour of other, thematically unrelated insights and methodologies suggested in Freud’s writings. The work of Susan Hiller – her art practice in installations such as From the Freud Museum 1991–6 (Tate T07438; fig.1) and related projects,4 as well as her teaching and her textual interventions – is in constant dialogue, both critically and sympathetically, with psychoanalysis. Hiller focuses on the cultural manifestations of a collective unconscious and also on the ways in which such manifestations are themselves the target of repression. This essay will discuss the under-explored and possibly censored relationship between psychoanalytic thought and the occult, but before doing so it will focus on an intrinsically psychoanalytic dimension of Hiller’s practice that inflects how audiences relate to works such as From the Freud Museum: that of transference.

Writer and psychoanalyst Jean Laplanche describes transference as the most transferable feature of psychoanalysis outside the clinic.5 It is also less well understood than other aspects of psychoanalytic therapy and yet without transference the specificity of the contribution of psychoanalysis can be misconstrued. The aggressive retrieval of repressed memories and wishes by an expert and dispassionate analyst from a passive analysand’s unconscious may have become a typical representation of Freudian methods (as in the conclusion of Alfred Hitchock’s 1964 film Marnie, for instance), but such narratives only perpetuate damaging misunderstandings. As Freud made clear in Wild Analysis (1910),6 for psychoanalytic treatment to have any chance of success, the analyst and the analysand must take time and make a mutual investment towards forming a relationship. Laplanche and Jean-Bertrand Pontalis describe transference as the ‘process of actualisation of unconscious wishes’ during which the analysand forms an attachment to the analyst that guarantees their commitment to therapy even when the going gets tough; this constitutes ‘the terrain on which all the basic problems of a given analysis play themselves out: the establishment, modalities, interpretation and resolution of the transference are in fact what define the cure’.7 Similarly, the mining of the cultural unconscious which drives Hiller’s practice has to be a collaborative operation if it is to work at all, and a mutual investment of psychic energy from both parties, the artist and her audiences, is necessary. Far more important than bringing the culturally repressed to light is the act of taking the viewer to the site of repression and provoking its recognition as such. The process is not altogether manifest nor primarily intellectual. As the critic Jan Verwoert has stated:

[W]hat Hiller can be seen to enact in her work is a form of criticality in art that comprises yet also goes beyond a critique of representation, by proposing terms for the critical engagement with those forces of transference that partially elude the visible and therefore can only be accessed in terms of a politics of sentience.8

One of the few scholarly works to address the relationship between psychoanalysis and the occult is described by its editor George Devereux as a contribution to psychoanalytic technique and specifically the problem of transference and countertransference (the analyst’s counter-attachment to the analysand). More broadly, it also has the potential to address ‘the sociological problem of human relations in general and of the social “dyad” in particular’.9 In some sense the occult is not external to psychoanalysis but located at its very core, within transference, its most essential feature. It is therefore not surprising that in ‘Psychoanalysis and Telepathy’ (written in 1921 and published in 1941), Freud found some ‘reciprocal sympathy’ between psychoanalysis and the occult and even the promise of an alliance, since they ‘have both experienced the same contemptuous and arrogant treatment by official science’; the two of them stand ‘in opposition to everything that is conventionally restricted, well-established and generally accepted’.10 Furthermore, and most strikingly, psychoanalysis has often lent a helping hand to ‘the common people against the obscurantism of educated opinion’.11 Their shared denigration, courageous knowledge-seeking and populism puts them on the same side. Their collaboration is possible not thanks to common beliefs but because, if psi phenomena such as extrasensory perception (ESP), precognition and psychokinesis were to be taken as facts, they would then fall under the remit of psychoanalysis and the laws of the unconscious would be assumed to apply to them.12 After all, as psychotherapist and writer Nick Totton notes, ‘[p]sychoanalysis has by necessity an extreme tolerance for the unknown’.13

Considering the extensiveness of the work he left behind Freud did not formally devote much attention to this potential ally. Yet it is not lack of interest that accounts for this relative negligence, but fear of being dismissed and ridiculed himself and of stoking the ‘contemptuous and arrogant treatment’ of psychoanalysis by the psychiatric establishment. In a 1926 letter to his friend and fellow psychoanalyst Ernest Jones, who openly discouraged him from pursuing his interests in the paranormal, Freud responded facetiously but revealingly, clustering together personal issues which are however inherently political: ‘My adherence to telepathy is my private affair, like my Jewishness, my passion for smoking, and other things, and the theme of telepathy – inessential for psychoanalysis.’14 Jones took this statement with more than a pinch of salt and in his biography of Freud cites the latter’s correspondence with psychical researcher Hereward Carrington in which Freud reportedly confessed: ‘If I had my life to live over again I should have devoted myself to psychical research rather than psychoanalysis.’15 Freud subsequently denied ever having made this statement, which Jones interpreted as classic repression: ‘In the eight years that had passed he had blotted out the memory of that very astonishing and unexpected passage.’16 That Jones should find Freud’s statement so ‘very astonishing and unexpected’, despite Freud’s avowed interest and their ongoing disagreement on the value of the occult, itself bears the mark of repression.

Freud’s bravery in his acceptance of psychic phenomena as legitimate objects of systematic investigation did not take him far enough. Here, as in the development of some key psychoanalytic concepts, his revolution remained unfinished, trumped by biologism – the interpretation of human life from a purely biological standpoint – and social and scientific pressures to conform.17 Yet the foundations for some important work had already been laid and such work has not always (nor, perhaps, primarily) been undertaken by psychoanalysts. Elaborating on Freud’s own characterisation of the cultural impact of his work in his lecture ‘A Difficulty in the Path of Psychoanalysis’ (1917),18 Jerome Bruner located the key intervention of psychoanalysis in the elimination of long-established discontinuities, including notably that between the primitive/infantile/archaic and the ‘evolved’/‘civilised’/rational, and that between mental illness and mental health.19 The purposeful transgression of boundaries (between content and context, among the boxes whose contents consist of an accumulation of contexts) is one of the most important effects of From the Freud Museum and Hiller’s work in general, as has been argued elsewhere in this In Focus project.20 Established theories and codes tend to defend the lines that multidisciplinary, scripto-visual conceptualist art finds easier to cross. As Hiller notes, although the distinction between rationalism and irrationalism may have been diversely and successfully challenged in both cultural and scientific practice, we remain ‘linguistically committed’ to it.21

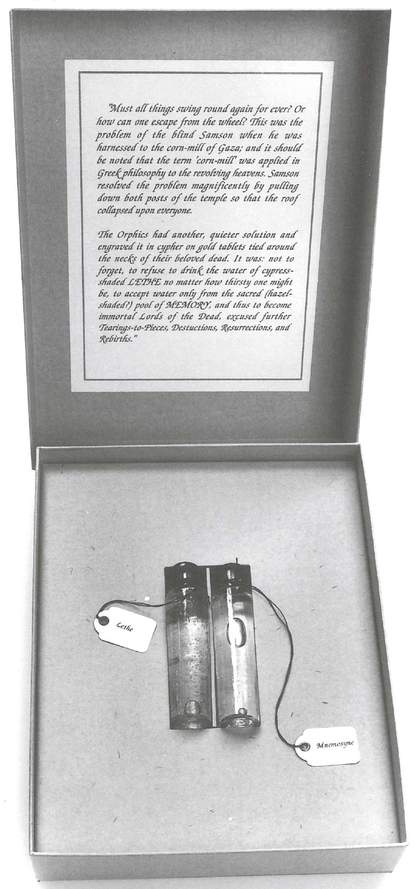

Fig.2

Susan Hiller

Homage to Joseph Beuys 1969– (ongoing)

© Susan Hiller

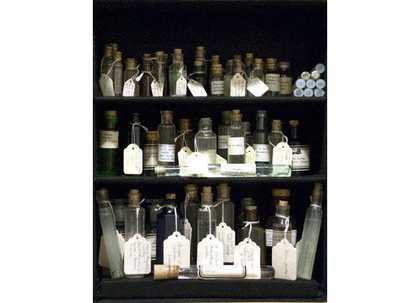

Fig.3

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum, box 011 Eaux-de-vie/spirits (annotated, 1993)

© Susan Hiller

On a studio visit some years ago, I observed Susan Hiller meticulously cleaning dozens of antique bottles of various shapes and sizes, for possible use in Homage to Joseph Beuys (collection of the artist; fig.2), an ongoing work begun in 1969 that consists of a growing collection of labelled bottles filled with water sourced from holy wells and displayed in a felt-lined recycled cabinet alongside felt squares. I thoughtlessly joked that I would be tempted to fill the bottles from the tap, were I in the artist’s shoes, but was immediately assured that adequate deposits of the holy waters were available and would be used for the work. According to gallerist Andreas Leventis, Homage to Joseph Beuys ‘simultaneously honour[s] and scrutinise[s] the ways in which [Beuys] attributed symbolic use to matter-of-fact materials, sacramentalised everyday activities and claimed to store up energy in ordinary objects.’22 Yet this difficult balancing of honouring and scrutiny does not necessitate or justify the trouble of sourcing and storing the water samples. The bottle labels are not merely signifiers but also accurate and honest descriptions of each bottle’s contents across the different works in which such bottles have been used, including From the Freud Museum. Nor is their symbolic value limited to Beuys or the paradigm of the artist-shaman, but shared, to different degrees and intensities, among wide communities beyond the art world. There are numerous photographs of the artist collecting water from the holy wells herself: among them from the spring of Lethe in Greece in 1990 and from Doon Well in Ireland the following year.23 Correspondence in 2000 between the artist and Linda Kaye, the Tate conservator of From the Freud Museum, confirms the authenticity of the waters’ sources. Two years after Tate’s purchase of the work lichen started to appear in the corked and wax-sealed bottles of some of the boxes, including 011 Eaux-de-vie/spirits (annotated, 1993) (fig.3) and 033 Vision/viz’hun (clarified, 1994), which needed to be cleaned as they had to remain enticing, like the ‘Drink Me’ bottles from Alice in Wonderland.24 The artist offered to undertake the water replacement herself, this time with sterilised samples from her personal supplies.

Another issue that cropped up in the conservation report of 2000 related to the devotional light bulbs with filaments in the shape of religious symbols in 043 Illumination/enlightenment (situated, 1995), which darkened due to accelerated carbon build-up in the high temperature of the vitrine interior. Tate ended up purchasing Hiller’s personal stock as the light bulbs were increasingly difficult to come by. A side-effect of the conservation work in this case is to chart the changing material supports of religious rituals and observance, as well as consumer culture more broadly: when Hiller included these devotional light bulbs in the work in the mid-1990s, incandescent bulbs were still the norm and devotional versions with shaped filaments were not hard to source on the high street, particularly in an urban capital as diverse as London.

Fig.4

Susan Hiller

Psi Girls 1999

Tate T12447

© Susan Hiller

Photo © Tate

The artist’s insistence not only on naming the holy wells on the bottles’ labels, but ensuring the authenticity of each water sample, deserves exploration. Is Hiller a believer? Could she or anyone believe in the powers of all of these diverse holy wells, which criss-cross and override different established religions and realms of spirituality? These, it turns out, are not the most apposite questions to ask. Hiller’s respect for spirituality and its manifestations is indicative of her artistic interest in the culturally repressed and intellectually maligned and should be understood in profoundly political terms. For instance, in Psi Girls 1999 (Tate T12447; fig.4), a video installation of five screens showing scenes from feature films in which girls display telekinetic powers, Hiller creates an immersive and ambiguous spectacle, suggestive of the widespread cultural fear of young womanhood and its disruptive potential. The soundtrack from each scene has been removed and replaced with a recording of the Gospel Choir of Canon’s Cathedral, Charlotte, North Carolina, consisting of handclaps and non-verbal singing. The added soundtrack simultaneously enhances the eerie quality of the sourced and manipulated scenes and seems to be cheering the girls on, in feminist celebration of their powers and the still unmined potential of their talents. Hiller’s Draw Together 1972, a mail art project inspired by experiments into ESP, referenced the telepathic investigations of Upton and Mary Craig Sinclair, whose sustained interest in direct mind-to-mind communication was entirely concurrent with their commitment to socialism.25

Political radicalism and spiritualism have historically been closer collaborators than psychoanalysis and the occult. As Hiller observes: ‘The spiritualist movement in particular made visible unacknowledged issues of gender and class relations, and, in fact, most of these otherwise varied groupings enabled women to take leadership roles and develop very public profiles.’26 When invited by an art magazine to write about what she had been reading, one of the books Hiller chose was Independent Spirits: Spiritualism and English Plebeians, 1850–1910 by Logie Barrow,27 which charts the history and debates of ‘working class empiricism’ and working-class attitudes towards science, religion, education and politics that, in Hiller’s words, ‘combined to create a complex, radical, visionary version of socialism’.28 Among the reasons why spiritualism survived the secularism of left-wing movements, Barrow cites the ‘plebeian concern to assert or retain control over one’s life’ and the right to self-education,29 especially in a country where social inequalities are so obviously sustained and reinforced through controlling access to educational institutions.

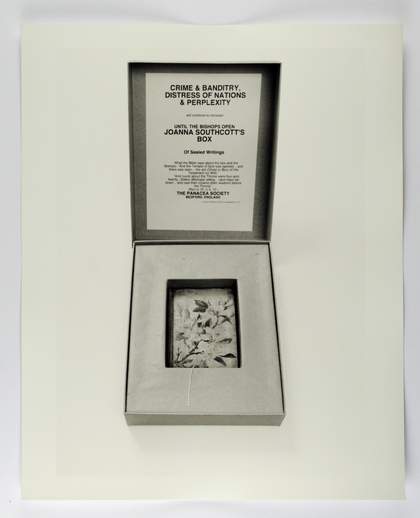

Fig.5

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum, box 003 Panacea/cure (filed, 1991)

© Susan Hiller

In From the Freud Museum, box 003 Panacea/cure (filed, 1991) (fig.5) focuses on the eighteenth-century mystic Joanna Southcott, a farmer’s daughter who acquired a large following thanks to her prophecies and her alleged pregnancy with the new Messiah at the age of sixty-four. In 1919 some of her followers formed the Panacea Society, according to whom Southcott had left a sealed box of writings to be ritually opened by a public convocation of all twenty-four bishops of England and Wales. The box is believed to contain a panacea, a universal cure that would revoke the sin of Eve and whose opening would usher in a new order. The bishops refused to gather together and open the box, despite repeated invocations by the Panacea Society, who took out annual newspaper advertisements urging them to do so up until the 1990s. Hiller’s box includes a copy of one such advertisement on the inside of its lid, alongside a biography of Southcott annotated and ‘extended’ by the artist, who added to it a bunch of dried flowers which she picked at Southcott’s grave in London. Hiller originally ‘collected’ the fragments of Southcott’s story when she was researching paranormal pregnancy for 10 Months 1977–9 (Moderna Museet, Stockholm), a series of ten composite photographs and texts exploring the implications of human reproduction for female subjectivity. Like Southcott’s pregnancy, the promise of her boxed prophecies never came to fruition: according to Hiller, ‘The moment of opening the box, of disclosing its revelation and (perhaps) bringing a new world into being, remains in abeyance, maybe forever.’30 Yet the legend of the farmer’s daughter-prophetess lives on in one of Hiller’s boxes, to be (re)discovered by each viewer.

The unanswered call of Joanna Southcott and her followers, commemorated in and perpetually disseminated through From the Freud Museum, captures something essential in this work and Hiller’s practice in all its manifestations: ‘an extreme tolerance for the unknown’31 and the unknowable; an unflinching commitment to unsettling the known; and a defiantly ‘reciprocal sympathy’ with all those who dare question ‘the obscurantism of educated opinion’.32 From the Freud Museum releases Freud’s contested legacies from the clinic, the museum and the gallery into sites of cultural and social possibility, where the unconscious activates a visionary politics.