Described by Hiller as ‘accumulations of contexts’, it is not only the diversity of the materials collected in From the Freud Museum 1991–6 (Tate T07438) that matter but also, importantly, that they stem from different orders, to which they allude only briefly and often casually. This essay considers the significance of the (dis)organising principles of collection and classification in From the Freud Museum by reviewing significant critical writing on the work as well as offering an original analysis. The array of contexts brought together in the installation are not only disparate but fragmentary: as Hiller has stated, ‘I deal with fragments of everyday life, and I’m suggesting that a fragmentary view is all we’ve got’.1

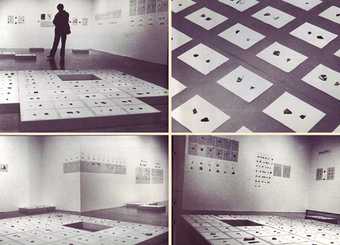

Fig.1

Susan Hiller

Fragments 1976–8

Installation view

© Susan Hiller

As is often the case in Hiller’s work, fragmentation is a potent metaphor that also gets literalised to draw attention to its own coding. Fragments 1976–8 (fig.1), an installation of broken pieces of Native American Pueblo pottery – traditionally painted by women – organises these fragments according to intersecting taxonomic systems that are inspired as much by archaeology and art history as by the creative principles according to which the Pueblo women were known to work. The staged confrontation between disparate and heterogeneous cultural codes and taxonomies underlines the political contingency of distinctions between the familiar and the unfamiliar. As curator David Elliot said of Fragments in 1978: ‘The irregularity and asymmetry of these hand-made and decorated fragments within the organised structure of the piece [suggests] a framework for alternative value-systems and perceptions.’2 The art critic Jan Verwoert considers the ethical dimension and gender politics of Hiller’s work with fragments and fragmentation, work that makes concrete, if not straight-forwardly visible, the usually invisible labour of curating as care-taking. Writing on the documentation of Fragments, Verwoert comments on two found images of women at work, not Pueblo women painting, but others, immersed in the seemingly less creative labour of sorting through and organising ceramic shards on an excavation site:

The female protagonists at work on this site of cultural archaeology take care of the fragments, relics and remainders that past economies of trade and transfer have left behind … Organising them is a material science. Yet this is also a science of the invisible, an endeavour hinting at absences through organised fragments. One could imagine this excavation site to be another portal into the zone where the subliminal forces of transference at play in culture are being witnessed and registered by a different kind of scientist, in this case, two autonomous women, working in a different spirit, as scientists of sentience.3

The gendered, impossible but essential position of the ‘scientist of sentience’ informs the making of From the Freud Museum: it is the position of the artist and also one that the viewer is invited to inhabit temporarily, or at least to consider. In addition to filling in the gaps in Freud’s collection – and Freud’s work – both in its earlier incarnation installed in the Freud Museum in 1994 (entitled At the Freud Museum) and in From the Freud Museum, the work opens up gaps that function as entry points for the viewer. Fragments and gaps inflect the quality of the encounter between the work and the viewer in ways that are more contiguous with the affective currents of psychoanalytic transference, rather than the mediated interactivity of other contemporary practices. Rather than physical interaction, From the Freud Museum performs an almost psychoactive function: it probes and mobilises in the viewer structures of feeling, thinking and being that exceed the perception of the work in the gallery and flow beyond it, in everyday life, at home, in encounters with the assumed familiar. As much as opportunities, the spaces opened up by From the Freud Museum are risky, possibly even dangerous. The artist has described the installation as ‘a film – fifty frames, and in the spaces between the frames, people construct their stories … I always wanted to “catch” people in the gaps, the gaps between discourses and the gaps between frames, in this work quite literally.’4 These openings function as both prospects and traps.

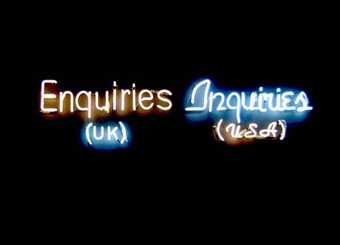

Fig.2

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum 1991–6, box 008 Cowgirl/kou’ gurl (collated, 1992)

Tate T07438

© Susan Hiller

The heterogeneity of Hiller’s collected contexts forms the focus of art historian and critic Denise Robinson’s approach to the work.5 Robinson casts From the Freud Museum in terms of a mimicry of a history museum inflected by Freud’s theories of the unconscious and repression as well as Walter Benjamin’s reflections on history, while also charting some important connections between the items collected in From the Freud Museum and the rest of the artist’s oeuvre, including Measure by Measure 1973 (Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris) and An Entertainment 1990 (Tate T06987). Torn out of its ‘original’ context, each collected artefact becomes a stand-in for that context but also acquires both new meaning and the potential to surprise. As Robinson posits, quoting philosopher Giorgio Agamben, ‘The shock is the jolt of power acquired by things when they lose their transmissibility and their comprehensibility within a given cultural order.’6 For Robinson, Hiller’s fragments, wedged into the gaps of both Freud’s collection and his worldview, do not suture them but create ‘a hyper-consciousness of their new status – a living breach’.7 The artist’s ‘gentle’ mimicry disturbs the logic of ‘Freud’ (of the Freud Museum collections; of psychoanalysis; as the name of the man and as a signifier with multiple and contradictory signifieds) until ‘the category itself becomes the artefact and all sources can become archives: The street; Tabloids; Museums; Toy shops; Magazines; Cinema; Texts; Rubbish skips.’8 From the Freud Museum explodes the archive with the aim of both undermining its will to order and of spreading its ambition all over the place. Hiller’s intervention in this museum and in the museum in general is not anti-historical but merely anti-historicist, resisting the compulsion to produce coherent narratives, to generalise, to assign the role of specimens to relics and remains. Far from being eradicated the museum is uncannily brought to life: in Robinson’s words, ‘The power of the fragment destroys the past in order to re-live it’.9

Fig.3

Susan Hiller

Enquiries/Inquiries 1973/1975

© Susan Hiller

In ‘Spirits and other Stories [Geister und andere Geschichten]’,10 a catalogue essay for Hiller’s 2008 solo exhibition Outlaw Cowgirl and other Works at the BAWAG Foundation, Vienna, curator Christine Kintisch assigned From the Freud Museum a central place in Hiller’s oeuvre, describing it as both a culmination of previous experimentation and a generative space for other works – including that given in the exhibition’s title. Outlaw Cowgirl 2006 (Zabludowicz Collection, London) consists of a small-scale installation comprising a framed print from a photograph of a woman holding a gun identified as ‘the outlaw Jennie Metcalf’ and four ceramic cow-shaped creamers on a shelf, one of which is intentionally broken.11 The nineteenth-century American cowgirl Jennie Metcalf made her first appearance in the earliest version of the installation, At the Freud Museum, as box 008 Cowgirl/kou’ gurl (collated, 1992) (fig.2), which includes a photocopy of the photograph used later in Outlaw Cowgirl and two identical cow-shaped china creamers, facing in opposite directions. The only comment on this box in the artist’s book After the Freud Museum (1995/2000) alludes to an earlier work by Hiller, Enquiries/Inquiries 1973/1975 (fig.3), an installation of two concurrent sequences of eighty slides each, shown on two slide projectors and consisting of entries from British and American encyclopaedias that reveal different orders of knowledge and modes of en-/inquiry across two cultures that share a language (more or less). Hiller, who moved to Britain from the US in her twenties, comments on box 008: ‘I never heard a woman called a cow until I came to England’.12 The box label in From the Freud Museum identifies Metcalf as an ‘American outlaw’, while the creamers allude to English teatime rituals in their playful tweeness. The artist here underlines her position as a resident alien who never ceases to be surprised, and occasionally shocked, by her adoptive culture. Yet Hiller’s persistent foreignness only highlights rather than exhausts her commitment to maintaining an ambiguous and ambivalent attitude towards her cultural settings: being both within and against one’s culture, perpetuating and changing it at once, is the job of the artist.13

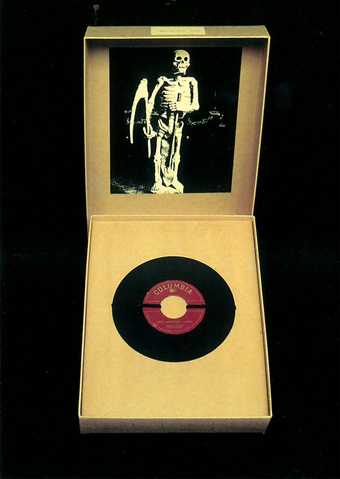

Fig.4

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum, box 020 Heimlich/homely (referenced, 1994)

© Susan Hiller

Kintisch is interested in a different kind of strangeness: the uncanny, an overdetermined concept not originating in psychoanalysis but more or less appropriated by Freud and, since then, by theories of post-structuralism and deconstruction. Drawing on writer and academic Nicholas Royle’s exhaustive study of the uncanny as well as a range of contemporary art theory and practice, from philosophers Slavoj Žižek and Giorgio Agamben to filmmaker David Lynch, Kintisch observes that most of Freud’s examples of uncanniness are associated with seeing, even though other senses are sometimes involved.14 Mining the cultural unconscious, as Hiller aims to do in her work, is bound to veer into uncanny territory and to produce uncanny effects. One of the boxes that explicitly references Freud’s writings, 020 Heimlich/homely (referenced, 1994) (fig.4), brings together a 45 rpm record of Johnny Ray singing ‘Look Homeward, Angel’ with a photocopied illustration of a Breton angel of death, to both evoke and overcome the affinity of the uncanny with vision. Sound, specifically the recorded human voice, presents as many if not more opportunities for uncanniness in Hiller’s work.15 In this one box, visual and material culture (the photocopied photograph of the statue of the Breton angel) are combined with music (the record) and literature (Look Homeward, Angel is also the title of ‘a novel by the once hugely-popular southern American lyrical novelist, Thomas Wolfe’, published in 1929).16 The angel in the novel is a graveyard statue while the home towards which he gazes is the soil of interment. As Freud himself observed in his writings, including Beyond the Pleasure Principle and ‘The Theme of the Three Caskets’,17 romantic love becomes interchangeable with death, as it does in Johnny Ray’s song. Pairs of apparent opposites, heimlich-unheimlich/love-death, contaminate each other through an ambiguity marked by ambivalence.

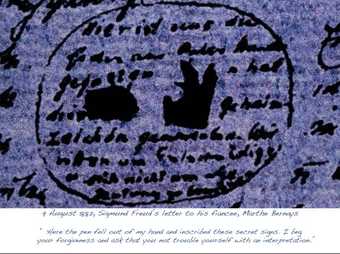

Fig.5

Susan Hiller

The Curiosities of Sigmund Freud 2005, detail

© Susan Hiller

Kintisch’s attentiveness to the uncanny is also sustained through another work by Hiller, The Curiosities of Sigmund Freud 2005 (various collections), shown in the exhibition Outlaw Cowgirl and other Works. This work comprises a set of nine Iris giclée prints on handmade Japanese paper, based on eight uncatalogued glass slides from the Freud Museum in London and a letter written by Sigmund Freud. With their enhanced graininess and added shadows, Freud’s family portraits resemble ‘fuzzy memory fragments’ or ‘afterimages, only blurred’.18 Having recently seen Hiller’s series of ‘spectral works’ (such as Vapours, Brown 2012, collection of the artist), described on the artist’s website as ‘several series of small photographic works in which the camera substitutes for the specialized vision of psychics’,19 I would suggest that The Curiosities of Sigmund Freud are also reminiscent of spectral photography, haunted and haunting in their opacity. One print consists of a detail in a letter from Freud to his then fiancée, Martha Bernays (fig.5); it is an aside, which Freud encircled as if in an attempt to contain it, that states ‘Here the pen fell from out of my hand and inscribed these secret signs. I beg your forgiveness and ask that you do not trouble yourself with an interpretation.’ The ‘secret signs’ in question stain the correspondence sheet as well as the precious handmade paper of Hiller’s prints and call to mind Jacques Lacan’s quasi-concept of the stain (or spot), namely that which is out of place in the picture and therefore draws attention to the screen – the unnoticed but essential support of the gaze as it differentiates itself from looking.20 What major function of the psychic apparatus do these stains make visible? Freud’s request to his other half not to trouble herself with their interpretation is tantamount to an invitation. To Hiller the stains conjure up one of the most intimate others of psychoanalysis: the occult.21

Fig.6

Susan Hiller

Witness 2000

Installation view

© Susan Hiller

Collection of the artist

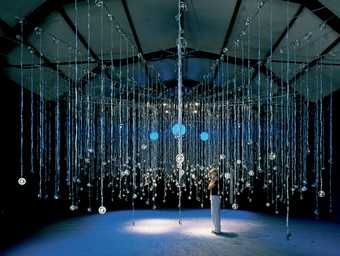

In addition to exemplifying Hiller’s approach to art practice as a distinct form of knowledge, From the Freud Museum functions as a virtual index of Hiller’s interests, principles and ways of working. There are allusions to important works by the artist in numerous boxes, including 040 Mar alta/rough sea (navigated, 1995), which references Dedicated to the Unknown Artists 1972–6 (Tate T13531). Consisting of 305 hand-tinted postcards of rough seas mounted on fourteen panels, alongside charts, maps, one book and one dossier, this profoundly conceptual work subjected its materials to methodical and methodological approaches and yet also exhibited what writer Brian Dillon has called ‘objects of such ravishing (and also kitsch) visual texture [which] is surely exactly what made the work, at the time, such a scandal for adherents of an austerely linguistic Conceptualism’.22 Other works made since the completion of From the Freud Museum are foreshadowed by it. For instance, box 048 Mantis/prophet (manifested, 1996), containing a photocopied excerpt from a House of Lords debate on UFOs and a praying mantis in a miniature glass coffin, prefigures Witness 2000 (fig.6), a sound installation of approximately four hundred speakers hanging from the ceiling on different wire lengths, forming an upside-down forest of dangling silver saucers through which recorded reports of UFO sightings can be heard in a great range of languages.

Fig.7

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum, 004 Slapstick/slaep’ stik (realised, 1991)

© Susan Hiller

The descriptive participles in each box’s label (‘curated’, ‘presented’, ‘filed’, ‘realised’) are unique, thus underlining the fragmentary and heterogeneous contents and contexts of the boxes, and resisting the identification of the work as an archive.23 Some participle choices have an air of whimsy about them: 019 Sophia/wisdom (sampled, 1993) includes waters from four sacred sites, which pilgrims ritually sample and from which the artist may or may not have drunk herself. 004 Slapstick/slaep’ stik (realised, 1991) (fig.7), contains a wooden slapstick, a photocopied photograph of a seaside performance of Punch and Judy and a stamp of Mr Punch under a magnifying lens, which causes monstrous distortions of his already grotesque face; this theme had indeed been ‘realised’ the previous year as An Entertainment 1990 (Tate T06987; fig.8).24 A video and sound installation commissioned by Matt’s Gallery, London, and purchased by Tate in 1995, An Entertainment is composed of four synchronised recordings of scenes from traditional Punch and Judy puppet shows. As with the cow(girl)s, Hiller brings to both box 004 Slapstick/slaep’ stik and An Entertainment the interested, analytical, mildly amused and genuinely horrified perspective of a foreign-born UK resident, restoring to this children’s spectacle the suppressed terror of domestic violence and infanticide that it so casually represents. 012 Fatlad/fat lad (addressed, 1993), discussed in more detail below, is ‘addressed’ because its title consists of the acronym of the six counties of Northern Ireland used by the UK post office, among other British institutions.

Fig.8

Susan Hiller

An Entertainment 1990

Installation view

Tate T06987

© Susan Hiller

Photo © Tate

In other cases the participles convey a specific action pertaining to the making process: 009 Führer/guide (bound, 1992) contains a discarded and partly burned copy of the book Jüdischer Geschichte und Literatur in vergleichenden Zeittafeln (Jewish History and Literature in Comparative Tables) by Julius Höxter (Frankfurt 1935), which Hiller rescued from a London skip and had rebound. Its conservation and preservation became as intrinsic to the object as the poor state in which it was found, in addition to the significance of the original form and content of the book. When opened the book unfolds into detailed charts, in which chronologically arranged historical and literary landmarks are contextualised by other events during the same period ‘thus showing the position of Jewish history within world history’; its author hopes the book will function as a ‘good guide’ in the education and later life of its intended Jewish readership.25 Considering the time of its original publication, Hiller surmises that the word Führer (guide) is used in the introduction to the book to deliberately evoke the other Führer, Adolf Hitler.26 The boundaries between content (text and objects contained in the boxes) and that which is seemingly presented as contextualising data (their labels) are repeatedly, insistently and meaningfully transgressed.

Fig.9

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum, box 012 Fatlad/fat lad (addressed, 1993)

© Susan Hiller

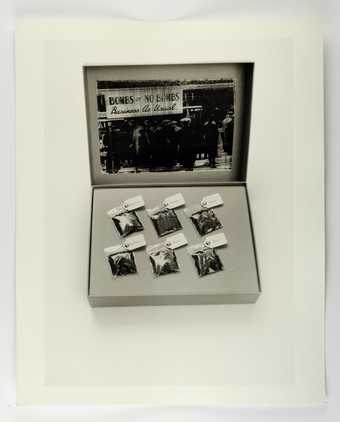

The resistance to classification that the descriptive participles in the titles of the boxes suggest does not mean that viewers do not or cannot arrive at their own groupings as they familiarise themselves with the work. I have long thought of boxes 012 and 039 as the ‘Irish Boxes’. 012 Fatlad/fat lad (addressed, 1993) (fig.9) pairs the acronym of its title for the six counties of Northern Ireland (Fermanagh, Antrim, Tyrone, Londonderry/Derry, Armagh, Down), which are ‘at present … part of the United Kingdom and its postal system’,27 with earth samples from each of the counties. The abstractness of the acronym, an easy-to-remember homonym for ‘fat lad’, is contrasted with the physicality and intense sense of place of the soil samples. The bagged samples look simultaneously clinical and fetishistic, recalling nationalist associations of ethnic identity with blood and soil; the label makes it clear that they were collected by the artist herself, suggesting that her personal presence in each of the counties was important to the constitution of the work. As always, the personal is profoundly political: a photocopied photograph of an everyday street scene in Belfast shows a group of men under the sign ‘BOMBS or NO BOMBS / Business as Usual’. In her commentary on the box, Hiller reminds us that ‘[t]he modern history of Ireland is about struggles over land and differing versions of business as usual’.28

Fig.10

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum, box 039 Deora de/God’s tears (analysed, 1995)

© Susan Hiller

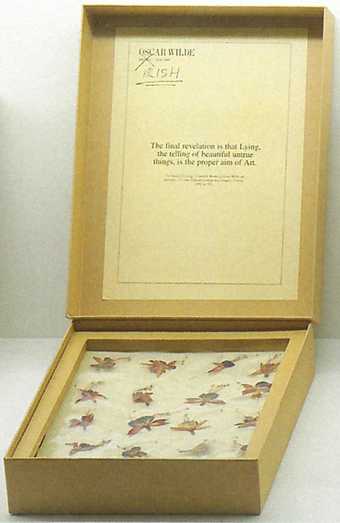

039 Deora de/God’s tears (analysed, 1995) (fig.10) includes a photocopy of an anonymously altered book page with an Oscar Wilde quotation. The alteration consists of the crossing out of the national identifier ‘British’ under Wilde’s name and its replacement with ‘IRISH’, in capitals, twice underlined. The quotation, ‘The final revelation is that Lying, the telling of beautiful untrue things, is the proper aim of Art’, comes from Wilde’s pseudo-Platonic dialogue ‘The Decay of Lying’ of 1889, set in ‘the library of a country house in Nottinghamshire’.29 Under the polish of Wilde’s biting satire that turns Plato’s scepticism of art on its head is a poetics in which artifice is valued both aesthetically and in terms of sexual politics. From a contemporary perspective, ‘the telling of beautiful untrue things’ may reference the need of Wilde’s homosexual community to keep a crucial part of their lives secret, but could also be cast as a form of world-making, a vital aspect of queer and decolonial cultural politics in action. Accused by the father of his male lover (whom he unsuccessfully countersued for libel), Wilde stood trial in 1895 and was found guilty of violating English Law, specifically Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act. He was sentenced to two years in Reading prison, which had a disastrous impact on his physical and mental health. In box 039 Deora de/God’s tears, dried fuschias from Donegal are presented in a slide holder. The box is titled after the flower’s name in Irish Gaelic, ‘deora de’ (God’s tears): its most common colours when fresh, hot pink and purple, have long been associated with both LGBT+ persecution and, by appropriation, activism for gender and sexual equality. The provenance of the fuschias arguably resonates with the traditional Irish folk song ‘Dear Old Donegal’, in which a returning emigrant is welcomed back from New York, where he has made his fortune, and reintroduced to his community by his mother: ‘you’re as welcome as the flowers of Spring in Dear Old Donegal’.30

Fig.11

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum, box 014 Moror/bitter (labelled, 1993)

© Susan Hiller

Fig.12

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum, box 015 Αδης/Hades (surveyed, 1993)

© Susan Hiller

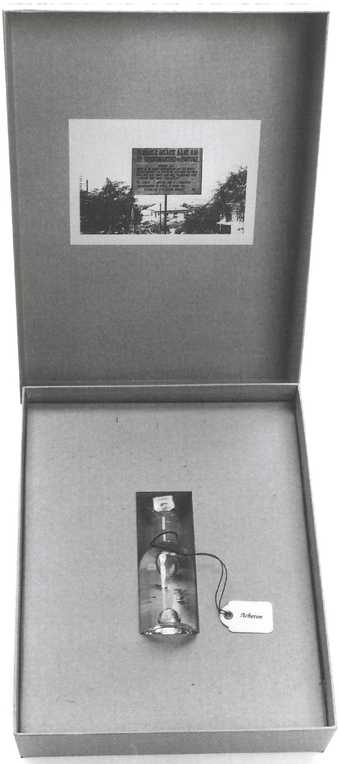

With From the Freud Museum Hiller complicates Freud’s Judeo-Hellenic worldview not only by looking elsewhere, at ‘home’ and abroad (Britain, Ireland, Latin America), but by revisiting the geographical and historical sites of this worldview, which was the norm for Freud and most of his educated contemporaries. 014 Moror/bitter (labelled, 1993) (fig.11) turns to the Jewry of North Africa, bringing together two books that Hiller acquired on a trip there and had since kept in her studio – ‘not on a bookshelf at home’.31 Their storage location highlights their status as objects rather than (only) text, or at least as artist’s materials. In their content both books discuss the long-established bonds between Arabs and Sephardic Jews in North Africa and the Middle East, bonds that have since turned sour (or ‘bitter’). An illustration showing an ‘Israelite Family (Famille israélite)’ in traditional dress is reproduced in the box lid and another is enlarged for inclusion in the artist’s book After the Freud Museum. The latter reproduces a fragment of a Haggadah, a Jewish text that explains the order of the Passover Seder, which includes moror (bitter herbs). The next box in the sequence, 015 Αδης/Hades (surveyed, 1993) (fig.12) contains a labelled sample of water collected by the artist from the river Acheron, the passage to the underworld according to Greek mythology, and a photocopied photograph of a sign in four languages (Greek, English, German and Italian) found ‘near the Necromanteion of Ephyra, ancient oracle of the dead and sanctuary of Persephone and Hades’.32 The Necromanteion had been replaced by an Orthodox church by the time of Hiller’s visit, complicating the religious affiliations of the site, which held spiritual significance as far back as the Mycenaean times.33 As Hiller described her experience there:

It was a hot day but it was cold in the shadows. Trying to scoop up some Acheron water from the deep ravine was difficult; the banks were slippery. I wondered nervously what I had wanted to find by coming here.34

It is not easy to remain unmoved in the face of such concentration of belief in one small piece of land and water. The sign in the photograph advertising a book on the Necromanteion in the four likely languages of visitors to the location both has a sobering effect and acts as a reminder of the site’s dark associations. Now a tourist destination and with a Christian church built on its foundation, the oracle makes its comeback as a revenant; it persists as a ghost.

In From the Freud Museum, Hiller operates as a trespasser: disciplinary boundaries are violated with impunity, reality and myth are melded into one as are memory and politics, and even geographic and historical distance is eliminated to joyful and disturbing effects. The low provenance of the materials used in the work and their aberrant classifications not only outline a particular artistic perspective on culture and its margins, but claim an important cultural and political role for art practice as a disruptive force.