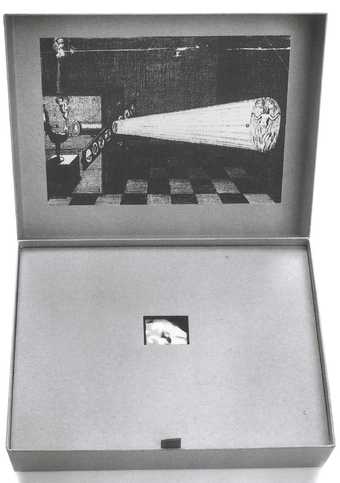

Fig.1

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum 1991–6

Glass, 50 cardboard boxes, paper, video, slide, light bulbs and other materials

Displayed: 2200 x 10000 x 600 mm

Tate T07438

© Susan Hiller

Photo © Tate

From the Freud Museum 1991–6 (Tate T07438; fig.1) is an installation of fifty labelled cardboard archive boxes, each measuring 330 x 255 x 65 mm, that contain found objects, photocopies and other materials, accompanied by an external projection of a video shown on a television monitor inside one of the boxes. Originally commissioned by Book Works for the Freud Museum in London in 1994 and shown there as At the Freud Museum that same year, the work mined the artist’s existing collections of ephemera and continued to grow until its completion in 1996. It is generally exhibited as a single vitrine in which the boxes are displayed on two shelves with their lids open, alternating between portrait and landscape orientation, revealing a broad range of small artefacts. Each box is numbered and labelled in subversive imitation of ethnographic and museological conventions of description and display, commenting on rather than describing their contents, complicating their meaning and often trumping expectations.1 Many of the items included in Hiller’s installation are ephemeral, such as dried flowers and confectionery; everyday articles, including 45 rpm records, crockery and toys; personal memorabilia, such as photographs and soil samples; and objects of historical and anthropological significance, including reproductions of aboriginal Australian cave paintings and modern copies of ancient artefacts. Many of the boxes juxtapose objects, texts and images of contemporary relevance or in current usage with those holding historical significance.2

From the Freud Museum brings together some of the most important and influential aspects of Susan Hiller’s art practice and has acted as both repository of and incubator for other works by the artist prior to and since its completion. Acquired by Tate in 1998, the work simultaneously deploys and challenges methodologies and forms of systematic taxonomy borrowed from disciplines such as anthropology and archaeology. It specifically engages with the overdetermined space of the museum, delving into its gaps and margins, to recast it as, in the words of curator Kynaston McShine, ‘a construct of the artist’s imagination’.3 Even though Hiller was granted access to the collections of the Freud Museum and was given permission to appropriate some of its uncategorised (and, arguably, least prized) holdings, most of the displayed objects came from the artist’s personal collections and were seamlessly slotted into what Hiller called ‘the gaps of the things left out’.4 Gaps open up in between Sigmund Freud, the London museum devoted to his life and career that occupies the last place where he lived until his death in 1939, and the diverse historical and contemporary reinterpretations of his work (the multiple ‘Freuds’ of psychotherapy, of critical theory and scholarship ‘outside the clinic’, of his champions and detractors). The blurring of the already fine line between archive and cabinet of curiosities is intensified by other challenges to culturally invested divisions: of property (the artist mixes her possessions with those of the Freud family), classification (each box brings together entities of different orders, each suggesting their own, absent archive) and appropriateness (the low status and possibly disturbing nature of the collected materials has often been remarked upon).5 As critic Guy Brett observes, ‘[t]he originality of [Hiller’s] practice is to work between these supposed oppositions and reconcile them in ways which seem of great importance for our future.’6

From the Freud Museum marks an intersection of two important currents in contemporary art practice, each explored in the various sections of this In Focus: firstly, a reflection on and intervention into museum spaces, collections and archives, and the resulting foregrounding of their inevitable lacunae; and secondly, an always ambiguous as well as ambivalent dialogue with psychoanalysis, its breakthroughs and silences. Freud haunts Hiller’s From the Freud Museum. This formally presented and curious collection reveals an artist perpetually shadowed by psychoanalysis both inside and outside the studio: in Freud’s last home, in Hiller’s own, in her research, on the trips abroad on which she collected many of the items, and in her various encounters with the familiar and the unfamiliar, with history, stories, politics and popular culture. As Hiller stated in 2005, ‘I think we all live inside the Freud museum, metaphorically’.7 From the Freud Museum presents an artistic intervention in a museum, a commentary on archives and collections in material form, as much as a perspective on culture and society that has been decisively shaped by Freud’s thought, not in agreement but rather in an often insolent dialogue with it. Delving into the Freudian Judeo-Hellenic world view and its material supports leads Susan Hiller and (some of) her audiences to consider what has been edited out, and the intellectual, cultural and political rationales for such exclusions. As Hiller stated in her artist’s book After the Freud Museum:

Freud’s impressive collection of art and artefacts can be seen as an archive of the version of civilisation’s heritage he was claiming; my collection is more like an index to some of the sites of conflict and disruption that complicate any such notion of heritage. My collection offers some indigenous symbols and references that position me – and maybe you – as outsiders who don’t understand things that make perfect sense to others. It includes disturbing materials that evoke moments of historical crisis.8

The earliest version of the work was commissioned by Jane Rolo and Susan Brind of Book Works in 1994 as part of a project in three cities called The Reading Room. This iteration consisted of twenty-three boxes. As its title suggests, At the Freud Museum9 was installed in Freud’s last residence at 20 Maresfield Gardens, London, now the Freud Museum, with the support of Erica Davies, director of the museum at the time, who granted the artist access to Freud’s private collections and facilitated the work’s installation on the site. Since 1994 the work grew through subsequent installations, including a 1995 show at Gimpel Fils in London, in which the boxes numbered 024–034 were added, and the artist’s one-person show at Tate Liverpool in 1996, where a total of forty-four boxes where exhibited. Boxes 001 Nama-ma/mother (curated, 1991), 006 Chamin-ha’/House of Knives (collected, 1992) and 019 Sophia/wisdom (sampled, 1993) were included in the exhibition World in a Box at London’s Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1994. Other notable exhibitions of From the Freud Museum include: Wild Talents/From the Freud Museum, Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide (1998); The Museum as Muse: Artists Reflect, Museum of Modern Art, New York (1999); Susan Hiller: Recall, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead (2004); Forms of Classification: Alternative Knowledge and Contemporary Art, Ella Fontaneis Cisneros Foundation, Miami (2006); Susan Hiller: Outlaw Cowgirl and other Works, BAWAG Foundation, Vienna (2008); and Museum Show 1, Arnolfini, Bristol (2011). The artist’s book After the Freud Museum, published by Book Works in 1995 and with a second edition in 2000, experiments with the format of the book as ‘a place where an artist works’,10 reflects on the experience of producing the first installation At the Freud Museum and includes short comments by the artist on a selection of the boxes that had been created by that time.

Fig.2

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum, box 022 Séance/seminar (edited, 1994)

© Susan Hiller

The fully fledged installation of From the Freud Museum contains fifty boxes displayed in a vitrine and is accompanied by a projection of Bright Shadow, the video work shown on a small television inside box 022 Séance/seminar (edited, 1994) (fig.2). Hiller explains that as well as collecting earth, water and fragments, she also collects shadows; the video was filmed ‘accidentally when a dark shuttered room spontaneously functioned as a camera obscura on a bright day some years ago’.11 The title of the box is a deliberate oxymoron and ‘plays with the supposed contradiction between rationality-irrationality; in French the word séance just means “seminar”. (I’ve used the title before, for a series of automatic writing works.)’12 According to the artist’s instructions to Tate for the installation of the ‘unboxed’ version of the video, Bright Shadow must be displayed with the boxes but separately, preferably in another part of the building, ‘as though it has escaped from the vitrine’.13 Additional strategies of distancing Bright Shadow from the displayed boxes include placing it substantially above eye level, as in its installation at Tate Modern in 2011.

Originally shot in Super 8 and transferred to video, Bright Shadow depicts the play of a shadow cast by ornate iron railings. Its placement in the gallery, its semi-abstract subject matter and the green hue and scratches from the original filming make the moving image difficult to decipher, thus underlining the aporetic dimension of the work as a whole, unsettling any acquired knowledge about Freud, the museum, his museum and collections, and what it means to collect and archive. The title’s oxymoronic dimension highlights Hiller’s ongoing disturbance of apparent opposites, and also evokes analytical psychologist Carl Jung’s work on archetypes,14 as well as spiritualist ideas that retain currency in the practice of Tarot. In this sense Bright Shadow presents the occult as the other of Freudian psychoanalysis, not quite censored but kept at bay and, of course, insistently making its return. Furthermore, the title Bright Shadow draws attention to the lexicalised metaphor of the shadow,15 a metaphor that visually captures the simultaneous omnipresence and marginality of the repressed, broadly defined. In the words of writer and critic Brian Dillon, From the Freud Museum is both exemplary and emblematic of Hiller’s long-sustained interest ‘in the shadowing of Modernism (and modern life) by occult intensities’.16

The installation and its display follows precise instructions given by the artist, including the gaps between each of the archival boxes, which should be equidistant at approximately ten centimetres, the portrait or landscape orientation of each box and the angle of tilt (twenty arc degrees). Intriguingly, the earliest date among the boxes’ labels is 1991, predating the commission of the first version of the installation (1994). This underlines the personal nature of the collection of the objects displayed and, even more so, its embeddedness in the artist’s art practice as a whole and its centrality to her approach to culture. Each box is assigned a three-digit number from 001 to 050, given a dual title, the second part of which is usually a translation of the first in either English or phonetics (for instance 006 Chamin-ha’/House of Knives; or 004 Slapstick/slaep’ stik), a participle describing the method of each box’s rendition (such as ‘realised’; ‘compiled’; ‘filed’; ‘sampled’), and finally the year in which each box was finished. The last boxes to be added are dated 1996, which has been accepted as the year in which the work was completed, although to write of the ‘completion’ of From the Freud Museum is in itself problematic. The collections on display both began and grew organically, following the artist in her physical travels and her mental journeys in, and mostly beyond, the boundaries of the Freud Museum. It is worth considering whether From the Freud Museum would have continued to evolve and expand had it not been purchased and housed in the Tate collection in 1998. In some respects From the Freud Museum is only From the Freud Museum at Tate, while the dissonant spirit of eccentrically drawing out, documenting and preserving the aberrant, the unarchivable and the culturally repressed continues to guide Hiller’s work. Notable instances of this aspect of her work include Homage to Marcel Duchamp: Auras 2008 (Dimitris Daskalopoulos Collection, Athens) and Homage to Yves Klein: Levitations 2008 (Herbert Gronemeier Collection, Berlin), two series of dry prints based on found photographs, as well as Lucidity and Intuition: Homage to Gertrude Stein 2011 (collection of the artist), an art deco writing desk packed with modified books on automatism and related issues, accompanied by a dossier compiled by the artist.

In 2000 Hiller curated Dream Machines, a national touring exhibition organised by the Hayward Gallery for Arts Council England. Here she brought together works by contemporary and earlier twentieth-century artists (including André Masson, Louise Bourgeois, Francis Alÿs and Lygia Clark) who have explored the interface between science, technology, the visual arts and altered states of consciousness, as she herself has done in Magic Lantern 1987 (private collection) and Dream Screens 1996 (Dia Art Foundation, New York), among other works. The concept of the ‘Dreamachine’, developed in 1961 by artist Brion Gysin and mathematician Ian Somerville and described by Hiller as ‘a marvellous low-tech device’17 that induces lucid dreaming, was not only a symbol for the whole show,18 but also of Hiller’s challenge to blunt divisions between different ways of knowing and hierarchies of knowledge. Hiller’s eccentric deployment of the superficial formalities of the archive provide the means for rethinking the organisation and transmission of knowledge and memory. In this sense, Hiller’s work displays affinities with French contemporary artist Christian Boltanski’s collections of data and material traces that simultaneously reveal and obfuscate their contents. The transformative encounter between psychoanalysis, popular culture and the everyday, so crucial to Hiller’s work, has emerged as one of the fertile interfaces between art and psychoanalysis. The theme has been developed by Zoe Beloff in The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and its Circle, a screening and lecture performed at the Freud Museum in 2009. The enduring psychosocial fallout of the interface between people, places and notable events is also explored in the work of Jane and Louise Wilson, whose early video Routes 1 and 9 North 1994 (private collection), in which the artists are shown being hypnotised in a motel room, was included in Hiller’s Dream Machines. Hiller’s influence on younger British artists, some of whom she taught, is widely acknowledged, while the numerous group exhibitions in which From the Freud Museum has been included suggest different constellations of artistic dialogues and convergences.

In its earliest incarnation as At the Freud Museum, the installation was among the first art projects made for and in response to the site of London’s Freud Museum and its collections, and in some ways set an influential precedent for what was to follow. Since 1994 the Freud Museum has had a consistent and expanding engagement with contemporary art, through a series of commissions, on-site art exhibitions, art events and conferences.19 Art installations in the Freud Museum after At/From the Freud Museum promote the reflective complication of the prepositions ‘at’ and ‘from’ inaugurated by Hiller’s work. The site-specificity of art made for or temporarily housed at the Freud Museum is heightened through a psychoanalytically inflected view of place as shaped by memory, while ‘from’ draws attention to Freud’s body of work as potential inspiration for artists,20 and highlights its own poetic and creative potential, from which Freud’s ideas clearly benefitted even though he sometimes sought to underplay the literary dimension of his writings.

From the Freud Museum remains one of Susan Hiller’s most viewed works, not least thanks to its display at Tate Modern.21 Reviewing it in the Guardian in 2000, critic Jonathan Jones remarked upon the artist’s background as a research student in anthropology and her persistent attention to ‘the unconscious of our culture, the margins of the collective psyche’.22 Reflecting on its first incarnation as At the Freud Museum, curator Kate Bush commented on the work’s engagement with the language and methods of psychoanalysis:

Hiller’s collection, with its functional specimen boxes and its array of shards and fragments summons a potent psychoanalytic metaphor: the plumbing of the human mind as an act of archaeology, an excavation of the unconscious where nothing is lost and everything is conceivably waiting to be disinterred.23

The two contextual perspectives identified above, namely Hiller’s critical engagement with psychoanalysis and with systematised knowledge more broadly, will be discussed in greater detail in this In Focus in the sections ‘Sites of Disturbance: Systems of Knowledge and Hiller’s Anarchival Impulse’ and ‘An Extreme Tolerance for the Unknown: Art, Psychoanalysis and the Politics of the Occult’. The former revisits classic theorisations of the archive by philosophers Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida and art historian and critic Hal Foster, in order to delineate the specificity of Hiller’s intervention as simultaneously asserting the capacity of art as an autonomous episteme and her refusal to define it in any concrete terms. The latter examines the repressed relationship between psychoanalysis and the occult, focusing on Hiller’s recovery of the occult in psychoanalysis and her insistence on its political significance.

From the Freud Museum casts art practice as cultural critique and an unfolding proposal for alternative forms of knowledge, its making, organisation and dissemination. More rebellious than what art historian Eric Fernie has termed ‘a branch of philosophy practised with materials and objects’,24 the definition of art implicit in From the Freud Museum highlights, questions and upsets the tacit assumptions of the academic settings from which Hiller consciously retreated. Rather than an artist informed by anthropology, she is a cultural producer who chose art over academic practice, for reasons that are elaborately and repeatedly articulated in her artworks and her words. Hiller’s practice may well be shadowed by that choice, but as it evolves it begins to suggest that such choices assume divisions that are both contingent and unstable. It is the division rather than one of the options (anthropology, academia, and so on) that Hiller’s work encourages us to question. From the Freud Museum does not announce itself as an alternative museum in its own right but an alternative to the museum. The work insists on its own status as an example of knowledge production and in doing so it offers an exemplary illustration of Hiller’s approach to art practice as an interdisciplinary yet independent method of knowing, and an autonomous and legitimate form of knowledge.