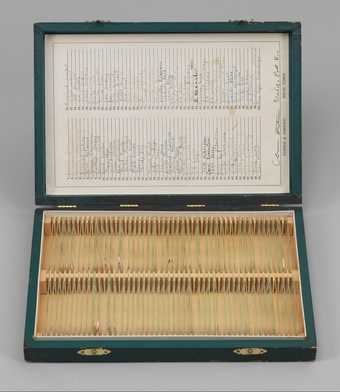

Fig.1

Eleanor Antin

Blood of a Poet Box 1965–8

Wood, cardboard, glass slides, blood, brass, paper and ink

Displayed: 28 x 290 x 405 mm

Tate T14882

© Eleanor Antin

Photo © Tate

Eleanor Antin’s Blood of a Poet Box 1965–8 (Tate T14882; fig.1) is a slightly battered, second hand, brass-hinged specimen box covered in green leatherette and containing one hundred numbered glass slides, each of which holds a blood sample taken from a different American poet, a category that Antin defined in broad terms to include dancers, artists and performers too. The blood drops were taken from their subjects using sewing needles. Each drop is sandwiched between the slide and a thin cover slip held in place by a clear sealant around its edge. The drops vary in size and positioning, and close observation suggests that there were at least two methods of application, with some blood drops squeezed onto the slides from a small height and some pressed in such a manner as to leave partial fingerprints. Inside the lid of the box is pasted a pre-printed form for recording the origin of the samples. Antin used a variety of pens and pencils on the form to catalogue these contributors, whose blood was added as Antin encountered them in the poetry readings and performance events that were a feature of the New York avant-garde scene during the 1960s. Below the list she has put her signature and written the title of the work.

Titled in homage to Jean Cocteau’s 1930 film Le Sang d’un Poète (The Blood of a Poet), Antin’s box was produced very early in her career, between 1965 and 1968, while she was living in New York. Antin has described Blood of a Poet Box as her first conceptual artwork.1 It represents a move away from writing poetry and creating paintings and collages towards a more conceptual practice that developed into performance and video work during the following decade.2 In its unconventional approach to the traditional genre of portraiture, Blood of a Poet Box relates closely to two series of ‘consumer portraits’ that Antin completed shortly after the box, while its exploration of themes of identity, originality and genius anticipates her later works of the 1970s and 1980s.

Making a poet box

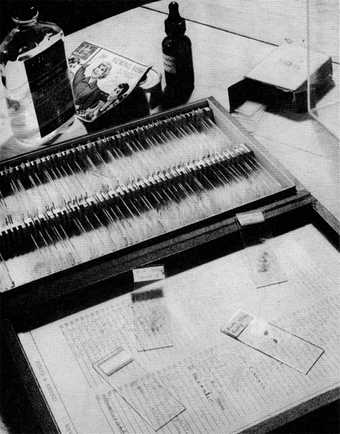

Fig.2

Eleanor Antin

Blood of a Poet Box with the items used in the work’s creation

© Eleanor Antin

Fig.3

Eleanor Antin

Blood of a Poet Box with the box lid closed

© Eleanor Antin

Photo © Tate

There was an element of serendipity at work in Antin’s choice of the materials that constitute Blood of a Poet Box (fig.2). She came upon the commercially produced box in a medical supplies store on 23rd Street in Manhattan (fig.3).3 She acquired it cheaply, because a change in the size of standard glass slides had rendered the box obsolete – too large for the new slides – and it had been discontinued by the New York manufacturer Eimer and Amend. As a result, the slides in Blood of a Poet Box rattled a little in the box, making the assemblage feel slightly unstable as she carried it. Antin was attracted to this outmoded and slightly faded object, as she recalled in 2009, because it was ‘a little fragile, a little old, something of a ruin, perhaps’.4 It also reminded her of artist Marcel Duchamp’s green archive box of loose documents The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors Even (The Green Box) (Tate T07744), created in 1934 to accompany his work The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) 1915–23 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia). Antin purchased the specimen box without knowing what she would do with it, but the idea to make a collection of blood samples soon presented itself to her.5 Although without a handle, the box was portable enough to take it with her to poetry readings. Diane Rothenberg, whose husband, the poet Jerome Rothenberg, was the fourth donor to Antin’s project, recalls Antin ‘hauling the box around’ New York’s small poetry venues over the nearly three years that it took her to complete it, between April 1965 and February 1968.6

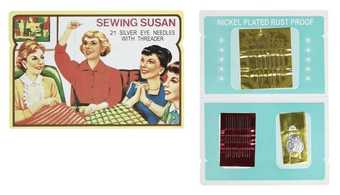

Fig.4

Sewing Susan 21 Needle Set, c.1950s

The needles Antin used to draw the participants’ blood had come from a Sewing Susan needle packet given to her by a child attending a kindergarten where the artist had worked during a brief period as a substitute teacher in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a neighbourhood of Brooklyn in New York (fig.4).7 The small cardboard wallet contained a selection of nickel-plated, rustproof sewing needles tucked into foil, along with a small threading tool. Mass produced and lightweight, the sets were sold cheaply and often given away as an advertising gimmick. Of course, these needles were meant for dressmaking, not drawing blood. Antin was not trained in medical procedures, and she has described her initial hesitation upon pricking the finger of her first volunteer and guinea pig of sorts, her husband, the poet and critic David Antin.8 As the project developed, her subjects expressed no such reluctance: according to artist Carolee Schneemann, ‘I could not refuse her rare request’.9

When Antin embarked upon making Blood of a Poet Box in 1965, she was primarily engaged in writing poetry and making hard-edge abstract paintings and large-scale collage works.10 This new project – which, as mentioned, Antin describes as her first work of conceptual art – represented a combination of her interest in written and spoken words and images. By the time she had collected all of the blood samples and had completed the work three years later, in 1968, she was preparing to leave New York behind to move to California, where she and her husband settled in San Diego. That Antin spent several years on the production of Blood of a Poet Box was typical of her working methods. Indeed, many of her other works were also undertaken over protracted periods. These include the photographic series 100 Boots, created over two and a half years between 1971 and 1973; The King of Solana Beach 1972–5; and Recollections of My Life with Diaghilev 1975–6, which itself was just one manifestation of her ongoing persona, Eleanora Antinova.11 This approach to making art emphasises process and performance as much as it does the resulting objects. While Blood of a Poet Box is important as a material object, it can also be interpreted as the relic of a performance that lasted several years.

The box’s first exhibition

Antin had not quite finished Blood of a Poet Box when it was first exhibited in her debut exhibition, entitled Flower Power: Eleanor Antin: Collages and Constructions and held at Long Island University, The Brooklyn Center, in 1968.12 The exhibition was suggested by Dana Collins, a painter who taught and exhibited there and who wrote to Antin in January 1968 to propose the idea.13 Antin showed Blood of a Poet Box alongside a group of collages made from pages cut from art magazines. A handful of the box’s slots remained unoccupied at the time, but Antin included the work in the show anyway. Its incomplete state at the time of exhibition and her decision to display the box alongside the equipment that she had used to extract the blood samples – rubbing alcohol, sewing needles and a bottle of the chemical xylol – support the idea that the process was important to Antin as well as the finished object.14 Although it was a last-minute addition to the exhibition, the piece gained some attention: explicit mention of it was made in several reviews of the show, including in the Village Voice, the Brooklyn Heights Press and the New York Times, whose critic Grace Glueck declared it the show’s ‘star exhibit’.15 Nonetheless, according to Antin the gallery itself, housed on the campus of a Catholic institution, expressed dismay at the work and asked that it be removed from the exhibition, reflecting a sensitivity, perhaps, to the way in which Antin’s blood samples mimicked the format of religious reliquaries and other sacred imagery.

Antin’s Flower Power exhibition was small in scale and staged in a lesser-known venue – reasons, perhaps, why it has been relegated to a footnote in art historical writing that has focused on projects by Antin that were more ambitious in scale and more widely known, such as 100 Boots. While the collages that comprised the main body of the show represented a brief foray into that medium, the ideas expressed in Blood of a Poet Box would be developed into some of Antin’s best-known work. Nonetheless, Blood of a Poet Box has received comparatively little attention in the art historical literature on Antin, which has tended to focus on performance works that are more explicitly feminist in approach or that sit more clearly within the field of performance art. Yet this early work remains one of Antin’s most significant.

This In Focus project seeks to rectify this omission, proposing Blood of a Poet Box as a crucial work among Antin’s oeuvre and situating it within the context of her ongoing artistic concerns, her major influences, and the contemporaneous art movements of the period. It analyses Antin’s project in relation to the New York poetry scene in which it was created, and the intermedia experiments reflected in her expansive definition of the term ‘poet’. It looks at the work’s connection to artistic, political and scientific debates about identity, as well as the history and conventions of portraiture as a means of depicting the self. It frames Blood of a Poet Box both in relation to historical precedents, such as Marcel Duchamp and Jean Cocteau, and to contemporary artistic practice, including the Fluxus movement. An interview with Antin conducted especially for this publication reveals her inspiration for the work and its meaning for her later in life. In addition, this In Focus reproduces ‘A Long Poem for Eleanor Who Collects the Blood of Poets’, a poetic homage written in 1965 by Diane Wakoski, whose blood is held in the second slide in Blood of a Poet Box.