Artist Carolee Schneemann has observed of Eleanor Antin’s Blood of a Poet Box 1965–8 (Tate T14882) that it demonstrated ‘a unique aspect of combining medical science, minimalism, ritual and community participation’.1 Blood of a Poet Box was notably of its time, in that it related to contemporaneous movements such as conceptual art, Fluxus and performance art, as well as drawing on significant artistic precedents including surrealism, dada and the work of Marcel Duchamp, who straddled these two avant-garde movements. In this way, Blood of a Poet Box suggests that Antin was as well versed in developments and debates in art as she was familiar with the New York poetry scene.

Cocteau and Duchamp

Blood of a Poet Box was loosely inspired by and titled for Jean Cocteau’s 1930 film Le Sang d’un Poète (The Blood of a Poet), which premiered in New York at the Fifth Avenue Playhouse in 1931 and was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art’s circulating film library shortly after the library’s establishment in 1935.2 The French writer, filmmaker and artist had enjoyed a significant reception in the United States since the 1920s, via little magazines and poetry journals such as Little Review, Transatlantic Review, New Directions and Kenyon Review, and this did not diminish in the post-war decades.3 Writing in 1957, a reviewer at the New York Times remarked that Cocteau was among those ‘contemporary French writers whose reputations in this country continue to grow’, and this remained the case into the 1960s.4 In the summer of 1964, an interview with Cocteau that had been conducted just before his death in autumn 1963 was published in English-language magazine the Paris Review.5 Several books on Cocteau appeared in English during that decade, including Wallace Fowlie’s Jean Cocteau: The History of a Poet’s Age, published by the University of Indiana Press in 1966; and Elizabeth Sprigge’s Jean Cocteau: The Man and the Mirror and Frederick Brown’s biography An Impersonation of Angels: Jean Cocteau, both published in New York in 1968. Cocteau was thus a key cultural reference point for American artists and poets.

In the post-war decades The Blood of a Poet was shown by independent film societies across America, including Frank Stauffacher’s Art in Cinema in San Francisco, Amos Vogel’s Cinema 16 in New York and Raymond Rohauer’s Society of Cinema Arts in Los Angeles. Received enthusiastically by this alternative cinema community on both coasts, Cocteau’s film was a significant influence on the circle of American experimental filmmakers labelled the New American Cinema.6 It also had an impact beyond film communities: Antin has highlighted the importance of European cinema in particular among her circle and the extent to which the ability to discuss newly released art house features served as an entrée into the alternative cultural circles of the New York scene.7

Fig.1

Jean Cocteau

Le Sang d’un Poète (The Blood of a Poet) 1930 (film still)

© Jean Cocteau

The first film in Cocteau’s Orphic Trilogy, The Blood of a Poet draws on the classical Greek myth of Orpheus to explore the relationship between an artist and his creation.8 In it, a statue comes alive, with harmful consequences that result in the suicide of the poet (fig.1).9 The sequence by which the statue is animated – in which the mouth from a drawn face is transferred first onto the hand of the protagonist and from there onto the marble figure – has been read by film and philosophy scholar Irving Singer as an allegory of the danger inherent in artistic or poetic expressions as creations that are capable of revealing the self.10 This interpretation chimes with Antin’s project in Blood of a Poet Box, which contains the bodily emanations of its one hundred poets as a metaphor for both the poetry that they produce and the source of their creativity. ‘I was sort of kidding around at first with the idea of the artist’s soul, his life’s blood’, Antin has explained. ‘So what, who, is a poet? I mean, what could be more basic than blood? Now they’d say DNA, so today you could say my blood box is a treasure trove of poet DNA, kind of ghostly, I guess, since by now, most of them – many of them, not most – are dead. But blood has a poetry to it that DNA doesn’t have.’11 In the case of the film, blood can be seen to signify the work of poetry and its tragedy: it represents both the distinction between the poet and the animated marble figure and the eventual mortality of the man from whose fatal, self-inflicted wound it flows. In the 1960s and 1970s, blood appeared literally or figuratively in performance, theatre, poetry and the visual arts, representing ritual catharsis, communion between artist and audience, the transgression of bodily boundaries, and the sacrificial commitment of the artist or poet, among other metaphorical or allusive functions.

Fig.2

Marcel Duchamp

The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors Even (The Green Box) 1934

Cardboard box, colour plate and 94 lithographs, collotypes and ink on paper

Object: 333 x 279 x 25 mm

Tate T07744

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

Fig.3

Marcel Duchamp

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) 1915–23

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/Succession Marcel Duchamp

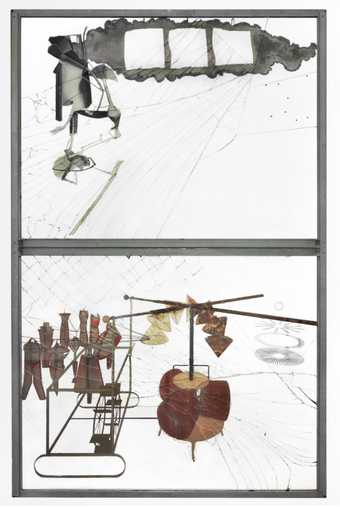

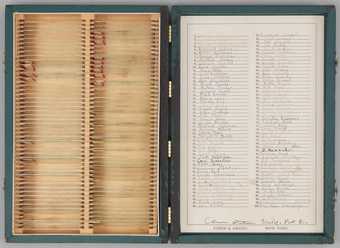

Although the box was initially inspired by her enthusiasm for Cocteau’s film, Antin has stated that she was influenced to an even greater degree by another European figure central to the American post-war art scene: Marcel Duchamp. In particular, Antin cites Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors Even (The Green Box) 1934 (Tate T07744; fig.2), the container of ninety-four notes, drawings, diagrams and photographs that Duchamp published in 1934 to accompany his work The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) 1915–23 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia) (fig.3).12 The Green Box notes were first published in English in 1960, although an edition of the work had been in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art since 1950, when it and a large number of other works by Duchamp, including a version of his Boîte-en-Valise (Box in a Valise), were transferred from the private collection of Louise and Walter Arensberg for permanent display at the museum.13 This key event in Duchamp’s American reception in the post-war decades was followed by the 1959 publication of Robert Lebel’s monographic study of the artist, complete with a catalogue raisonné, and Duchamp’s first US retrospective exhibition, at the Pasadena Museum of Art in 1963. His presence on the American art scene during the post-war decades was therefore considerable and played a part in shaping much art of the period.

Fig.4

Eleanor Antin

Blood of a Poet Box 1965–8

Wood, cardboard, glass slides, blood, brass, paper and ink

Displayed: 28 x 290 x 405 mm

Tate T14882

© Eleanor Antin

Photo © Tate

The similarities between Duchamp’s box and Antin’s are both material and methodological. Antin’s box, like Duchamp’s, is green, and it too references the medium of glass as ground for the visual image (fig.4). Duchamp stated that he created The Green Box in order to avoid purely formal responses to The Large Glass. If Duchamp’s Green Box functioned as a key – albeit an enigmatic one – to his Large Glass, then Antin’s box might be seen as a key to the identity of the hundred poets to which it referred. Antin’s and Duchamp’s boxes also share an interest in creating art from scientific procedures. The ninety-four fragments that comprise Duchamp’s collection contain technical and mathematical diagrams, measurements and angles, which give the collection an air of scientific exploration and discovery. Furthermore, Duchamp’s insistence on reproducing, via printmaking, each handwritten note, complete with torn edges, erasures and annotations, indicates a concern with exploring the relationship between apparently identical objects that are nevertheless ontologically distinct in fundamental ways.14 Antin’s interest in scientific methods was similarly twofold: on the one hand, she utilised the apparatus and procedures of biological science in her appropriation of the specimen box and the process of drawing blood. On the other, Blood of a Poet Box represents an investigation into the nature of biological identity and classification. The samples all look the same, but they are different at a fundamental level. When subject to scrutiny, blood reveals both a universal humanity and individual identities.

Indeed, Antin’s adoption of medical procedures is seemingly undermined by the lack of uniformity between blood samples: according to the artist, she was initially hesitant, becoming more confident as the project developed, resulting in smaller drops from early contributors and larger ones for the later ones.15 Furthermore, the samples were not subject to the usual chemical treatment for preservation, and so have degraded, becoming unusable as actual medical samples and now devoid of DNA. Subjective narrative is inserted into the apparently objective space of the scientific specimen, reminding the viewer that Antin was not, after all, a doctor or nurse, but an artist unaccustomed to drawing blood, especially at the start of her project; her subjects were not patients, but poets.

Antin’s citation of Duchamp’s Green Box as an influence situates Blood of a Poet Box within the trajectory of Duchamp’s American legacy charted by, among other art historians, Benjamin H.D. Buchloh. He outlines three stages to Duchamp’s post-war reception in the United States: the first occurred in the work of so-called ‘neo-dada’ artists such as Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg; the second, in the structural or linguistic approach of conceptual artists such as Robert Morris; and the third in the dismantling of art’s categories and hierarchies, a manoeuvre that critic and curator Lucy Lippard termed ‘the dematerialization of the art object’.16 Blood of a Poet Box appears to straddle all three phases, demonstrating a clear relationship with neo-dada and conceptualism, and echoing the emphasis on process and performance that is often associated with practices that sought to circumvent the commercialism associated with the art object as a thing of value.

The assemblage, the found object and the box

Fig.5

Robert Rauschenberg

Odalisk 1955–8

Oil, watercolour, crayon, pastel, paper, fabric, photographs, printed reproductions, newspaper, metal, glass, pillow, wooden post and lamps on wooden structure with stuffed rooster

2108 x 641 x 688 mm

Museum Ludwig, Cologne

© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

The clearest link between Antin’s Blood of a Poet Box and that of the neo-dada artists lies in her incorporation of found materials (the commercially produced box and its slides). This strategy aligns her with the practices of artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, who had incorporated found and bought objects and personal artefacts, including clothing, photographs and domestic items, into his ‘combines’ (see, for instance, Odalisk 1955–8; fig.5). Antin has drawn a connection between these and large-scale works she described as ‘assemblage collages’ that she was producing prior to Blood of a Poet Box and that were exhibited alongside it in 1968.17 In their three-dimensionality and their incorporation of found elements including rope, paper, metal, fabric and wood, such works could be considered ‘baby Rauschenberg[s]’, she has suggested.18

These qualities align Blood of a Poet Box with the practice of assemblage, a term popularised in the United States by William C. Seitz, curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. His exhibition The Art of Assemblage was staged at the museum in 1961, and included works by Duchamp, Max Ernst and other surrealists, as well as post-war American artists such as Rauschenberg, Joseph Cornell, Jasper Johns and Edward Kienholz. Although Antin is quick to resist labelling her work according to established movements, Blood of a Poet Box seems to conform to Seitz’s definition of assemblage in that it incorporates readymade objects into an artwork, although it fits less comfortably his assessment of assemblage as ‘junk art’ – art that refers predominantly to the detritus of the contemporary city.19

Seitz located the intellectual and material lineage of assemblage in dada, cubism and surrealism. The use of objets trouvés (found objects) was a key surrealist strategy, one practiced by the group in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s and then brought to the United States when many of its members were exiled there during the Second World War. If Duchamp and other dada artists were attracted to found objects on the grounds that they occupied an anti-art status as low, mass-produced objects, the surrealists saw them as a way of accessing the realm of the marvellous, offering a more poetic point of reference for Antin’s project. She cites surrealism as an important influence, enthusiastically recalling school days spent at the Museum of Modern Art viewing paintings by Pawel Tchelitchew, Salvador Dalí and Giorgio de Chirico, as well as Ernst’s Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale 1924, which incorporates pieces of wood, cork and a doorknob.20 This work’s combination of found materials and a dream narrative reflected a wider interest among surrealist artists and writers in exploring the permeable boundaries between interior, psychic worlds and exterior material reality. For Antin it provided a clear point of reference for her Blood of a Poet Box, as she embarked upon an exploration of inner genius made manifest.

Fig.6

Joseph Cornell

Planet Set, Tête Etoilée, Giuditta Pasta (dédicace) 1950

Glass, crystal, wood and paper

305 x 457 x 102 mm

Tate T01846

© The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

The body of work to which Antin’s seems most akin is that produced by the American surrealist artist Joseph Cornell, whose delicate ‘shadow boxes’ displayed miniature collections of often outmoded objects redolent of Victoriana and childhood games, in order to create enigmatic and poetic narratives – see, for example, Planet Set, Tête Etoilée, Giuditta Pasta (dédicace) 1950 (Tate T01846; fig.6). Cornell’s interest in natural history, pharmacy and astrology resulted in works that combine scientific investigation with poetic presentation, an approach that finds significant echoes in Antin’s box. The resonances between Cornell’s and Antin’s works have been remarked upon by art historians, but although Antin acknowledges thematic and poetic similarities, she has stated that she was not consciously influenced by Cornell when she made her own box.21

Boxes were something of a feature of much avant-garde art in the New York art world of the 1950s and 1960s, and both Cornell and Duchamp were clear precedents for a trend that was manifested across the US and Europe. In 1964 the gallerist Virginia Dwan had staged an exhibition entitled Boxes at her Los Angeles gallery, exhibiting box works by thirty-nine artists, including Duchamp, Cornell and Kurt Schwitters, as well as young contemporary artists Rauschenberg, Robert Morris, Jim Dine, James Rosenquist and Andy Warhol. The multi-media avant-garde publication Aspen released several issues in box format between 1965 and 1971.22 In 1970 David Antin, the poet and husband of Eleanor Antin, contributed a text work entitled ‘3 Musics for 2 Voices’ to Aspen’s eighth issue, which was edited by artist Dan Graham and designed by George Maciunas.23 Throughout the later 1960s, boxed works of art were routinely produced by those associated with Fluxus, an international network founded in 1960 by Maciunas. Artists such as Ben Vautier and Ay-O, both associated with Fluxus, routinely created boxed artworks that evoked the mass production and easy portability of consumer products, as well as the ludic possibilities of puzzles and games. Blood of a Poet Box shares visual similarities with Fluxkits and boxes, and its inclusion of Fluxus members Philip Corner, Alison Knowles, Jackson Mac Low and Emmett Williams ties it to the constellation of artists, designers, composers and poets who comprised the group, even though Antin herself was not a member. She has distanced herself from the group on the grounds that she did not share their interest in typography and design;24 it is also possible to discern a different approach to collaboration in that Antin’s project harnessed the contribution of others during the production of the box, whereas Fluxus boxes are created first in order to elicit a participatory encounter. Furthermore, whereas the Fluxus manifesto declared its aim to be ‘to promote living art, anti-art, promote non art reality’, Antin’s box seems to be positioned more ambiguously in relation to traditional art and its histories.

In addition to presenting a snapshot of New York’s poetry scene during the second half of the 1960s, Blood of a Poet Box displays clear relationships with contemporaneous art practice and discourse. This is reflected in its connection, along with much American art, to earlier European avant-gardes including dada and surrealism, its explicit allusion to the work of Cocteau and Duchamp, and its embrace of a collaborative mode of meaning creation that aligns the work with a wider shift towards participatory art and performance. Antin’s box is thus very much of its time, even as it looks forward to the next phase of her oeuvre.