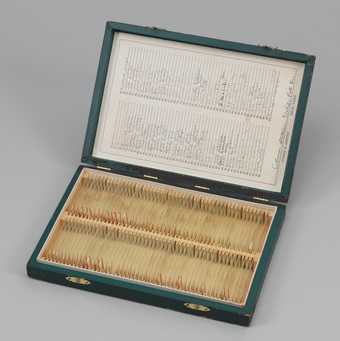

Fig.1

Eleanor Antin

Blood of a Poet Box 1965–8

Wood, cardboard, glass slides, blood, brass, paper and ink

Displayed: 28 x 290 x 405 mm

Tate T14882

© Eleanor Antin

Photo © Tate

In this interview, Eleanor Antin and Lucy Bradnock discuss the conception and making of Blood of a Poet Box 1965–8 (Tate T14882; fig.1), and consider the work’s relationship to the portrait, the memorial and to art historical tradition. The interview was conducted specially for this publication via a series of emails between August and October 2014.

Lucy Bradnock: Do you remember how you came to devise the project of Blood of a Poet Box? Where did you acquire the box? Did you have a plan for it, or did the idea for the work develop later?

Eleanor Antin: I majored in writing in college and was writing poetry and married to a poet [David Antin] so I went to a lot of poetry readings. The New York poetry scene was exploding with innovation and I was reading in some of the open readings. I also began publishing some of my poetry in the magazines. But I didn’t consider myself a poet. It didn’t satisfy me. I was also painting. I guess they were pop paintings. I remember a series of valentines, large canvases with black or white or even red valentines that were too big for the canvas and were cut off by the edge. Sometimes I painted a large canvas envelope to go with them, white canvas with tape to suggest a flap. They were always too small for the valentines. Big but not big enough to send a single valentine.

I began collecting the blood specimens because some of those readings went on all night and groups of us were half asleep sitting along the walls. So I figured I should do an artwork instead of getting drunk and being bored. Pretty soon, I was much more interested in collecting my blood specimens than listening to the poetry. I set myself up in a corner and used sewing needles and the slides and slide covers that I got from a science store. The box came first. I saw this old green box, very dilapidated looking, in the window of a science shop. It was selling its older stuff because the size of the slides coming into fashion were smaller than the older ones that had been made to fit the older slide boxes so nobody wanted those boxes anymore. I thought of Duchamp’s green box and bought the poor old thing for a couple of bucks along with the new smaller slides.1 So my slides are a bit small for the box. It struck me as rather touching. They wobble a little when you carry it. So from the beginning you had to treat the box with respect and care. I had no idea then what I would do with it. But sitting in those endless poetry readings, it came to me pretty quickly.

Lucy Bradnock: How did you choose your ‘contributors’? Were they all friends of yours?

Eleanor Antin: I knew a number of my poets but not all. Pretty soon, I was a familiar fixture. I took specimens from all poets. How did I know they were all poets? If they were there at the poetry readings, they were poets. Who else would come? Some were famous. Some were young. A number are dead by now. Some refused to give blood. Like Frank O’Hara. ‘Sperm, yes’, he said. ‘Blood, no.’

Lucy Bradnock: How were you defining ‘poet’? Did the definition change over the course of the project?

Eleanor Antin: In several cases, I used the word poet in the specific, more personal way that I tend to use it. There were so few women poets in those days, at least at the readings. So when I had the chance to get Yvonne Rainier’s blood and Carolee Schneemann’s blood, I used my definition of ‘poet’ to include them. After all, Yvonne is a wonderful writer and they’re both great poetic artists.

Lucy Bradnock: Were there any poets that you wanted to include but couldn’t for some reason?

Eleanor Antin: Yes, there was one poet, a great one, that I could have gotten but didn’t. A couple of us were going out to dinner with [Pablo] Neruda who was in town to read at established places, not dark dingy ones like ours. But he wanted to meet some younger poets. Somehow, David and I and Jerry and Diane Rothenberg went to dinner with him at Emilio’s, a dinky Italian restaurant with an outdoor garden on 6th Avenue near Canal St. I planned to take my box and needles but David begged me not to. He was convinced that Neruda, a Nobel Prize poet, who was pretty old at the time, and from a totally different culture, would freak out or be insulted or whatever at such an unexpected request. So I gave in. Shit! When Neruda walked in, with his wife on one arm and his mistress on the other, and sat down with a beaming smile after kissing my hand, I knew he would have graciously given me his blood. I leaned over to David and whispered in his ear. ‘When we get home, your ass is grass!’ If I didn’t live so far away in Brooklyn, I would have grabbed a cab and run back for the box but with the lousy traffic, I’d miss most of the conversation. Besides I was hungry. I’ve always mourned that loss.

Lucy Bradnock: Are the slides portraits of their subjects? Should we understand them as individuals or a homogenous group?

Eleanor Antin: In a sense they’re portraits. ‘Portrait’ seems like such an easy word but in art language, it’s quite complicated. For instance: Rembrandt’s portrait of his son probably looked like his little boy but added to with the tenderness and sweetness his father felt for him.2 You can see it in the image. But who is that portrait of the thin, tormented man in a loincloth hanging from a cross? We recognise Jesus, or at least the Roman Catholic Jesus, because it’s an iconic resemblance, endlessly repeated. Did it look like him back then? [shrugs] Probably the tormented part did, the way of hanging in that position. One knee is always crossed. Is that to prevent the nail from tearing at the foot more violently or does it add more glamour? Models like to stand that way. Remember the Romans went in for crucifixions a lot. When the slave revolt led by Spartacus was crushed after three years, the remaining 3000 slaves were all crucified along the Appian Way. So every Roman man, woman and child knew how those dead and dying people looked. The way, I suppose, Middle Easterners will know everything about rolling heads when jihadists conquer the whole area and hold weekly beheadings. And if they have any coliseums or stadiums, the events will be even closer to the Romans. You can buy a hot dog in between events.

But now take Mary. When she’s holding the baby, we know she has to keep him from falling, maybe give him a breast, pet him. But why does he never piss all over her skirt and make her wipe it up? Or scream with fury? Or try to climb off her leg and play with a ball? Where are the peculiar details of each mother and child? We’re back to icons again. So are my blood specimens portraits? I suppose if you know how to extract DNA you could find out a lot of personal info. But the art viewer doesn’t do that. So I think they’re portraits in a general way. By calling one slide Michael McClure and another Allen Ginsberg I give them a name and a body of work so they aren’t merely iconic portraits.3 They were real... once, at least.

Then there’s the fact that I began taking blood more timidly at the beginning. I didn’t want to hurt anyone. So the earliest blood drops look sparer and less generous than later on when I became a pro and punched in the needle and squeezed a hefty amount of blood out, gave them their piece of alcohol cotton to prevent infection and called out ‘next’. As a result those later poets look more passionate, stronger. Just the way the ball bounces.

So my poets are both a homogenous class and individual portraits at the same time.

Lucy Bradnock: Do you see it coming out of your poetry at all, or do you think that it signalled a shift in approach?

Eleanor Antin: I hadn’t thought of that relationship before but actually there is one. My poetry was built up of collage elements through which narrative relations were often trying to get through.

Fig.2

Eleanor Antin

Representational Painting 1971 (film still)

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

© Eleanor Antin

Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Lucy Bradnock: Later works such as your 1971 film Representational Painting (fig.2) and the installation Carving: A Traditional Sculpture 1972 (Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago) seem to relate to your interest in traditional art and modes of self-presentation – do you think that Blood of a Poet Box could also be seen as a kind of response to art historical convention?

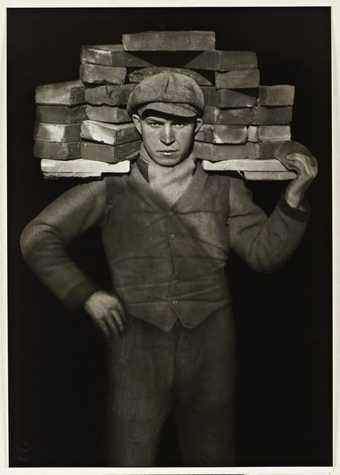

Fig.3

August Sander

Bricklayer 1928, printed 1990

Tate AL00038

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne; DACS, London, 2018

Eleanor Antin: Modernism, especially the late modernism of that time, was always allergic to narrative. I think an artist like [German photographer] August Sander [1876–1964] tried to follow the modern dictates by naming his portraits by profession – Postman or Plumber – thereby attempting to remove personality from them (fig.3). But it didn’t work, not even with Germans. There are suggestive differences, a uniform isn’t sufficient to erase individual physical habits and quirks. Sander made an anthology of working class and bourgeois occupations in a certain time and place. I made a poetry anthology in the mid-1960s. Is the blood of a plumber or a postman different from that of a poet? Or if I had made my box in the nineteenth century, would the blood of [Romantic poets Percy Bysshe] Shelley or Elizabeth Barrett Browning be different than that of Barbara Guest or Jerome Rothenberg today?

Fig.4

Eleanor Antin

Jeanie 1969 from the series California Lives

Collection of the artist

© Eleanor Antin

Lucy Bradnock: I suppose not, or at least they would appear no different. Speaking of uniforms, or material attributes, how does Blood of a Poet Box relate to the consumer portraits (California Lives 1969, fig.4, and Portraits of Eight New York Women 1970, collection of the artist)?

Eleanor Antin: The consumer goods sculptures are portraits of people from the late 1960s. California Lives was a white New York street brat’s response to the exotic white trash culture and its inimitable country and western music that she fell in love with when she moved to San Diego. My Portraits of Eight New York Women, while stylistically similar, was very different and the women represented were perhaps more complex and less sociological. Yes, the consumer goods portraits were also a version of traditional art.

And remember a painted subject is not only a portrait of a person but also a portrait of the painter. Every photograph of Diane Arbus [1923–1971] is a portrait of herself even though she never appears in any of them.

This piece is very personal. I may not have my blood in it, but part of my life is in it.

Lucy Bradnock: The work’s title refers to the 1930 film The Blood of a Poet by Jean Cocteau – when and where did you see the film? Would you say that there are symbolist and/or surrealist aspects to Blood of a Poet Box ?

Eleanor Antin: I can’t remember when I first saw the film. And I don’t use art historical labels to describe my work. I think I responded to Cocteau’s magic. And its absurdity. The French are so good at marrying magic and absurdity.

Lucy Bradnock: You’ve described Blood of a Poet Box as your first major conceptual work. Which was more important: the process of collecting the samples or the material qualities of the work as an end product?

Eleanor Antin: It’s one of my favourite pieces. I enjoyed doing it and I love the idea of it. Sometimes I lightly rub my hands across the slides to feel the rough edges of the glass. So much life is in that box and so much of it is gone.

Lucy Bradnock: It seems to tread an interesting line between ephemerality and permanence. I wonder whether the fading of the blood affects the meaning of the work. Now that many of its subjects have passed away, does the work become a memorial?

Fig.5

Leonardo Da Vinci

The Virgin and Child with St Anne c.1503

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Photo © Dennis Jarvis

Eleanor Antin: In a way, I suppose it does. Though it wasn’t when I made it. Life does that to us. Time doesn’t stop. Tyrannosaurus rex is both a portrait and a memorial, isn’t it? It’s an object that gives us information about a long dead creature who searched for food, had children, fought with enemies, escaped the rain when he could and fucked when he could. There’s no way of looking at his assembled skeleton or even a single bone and not feeling the power of that life and its extinction. When I went to the Louvre in Paris for the first time, the first room I entered was filled with Leonardos. (I don’t mean the Mona Lisa [c.1503–6], that’s a tedious, uninteresting work that’s kept in a room of its own so poor deluded Japanese students can take her picture over and over again.) That left Leonardo’s St Anne and the baby Jesus and Mary and their family, clear for me to see (fig.5). Nobody cared about them. Except for me. The tears started streaming down my cheeks, even now as I write this, the tears start to fall again. Leonardo was never one of my favourite painters, not by a long shot, but suddenly there he was and he was real. Those paintings weren’t the slides and reproductions I had seen in books. Leonardo himself had stood in front of them, thought about them, discussed them, made changes, as he and his atelier painted those pictures. They were real. They had existed once in his space and now, through all those centuries, they existed in mine.