Art historians of the late twentieth century were adept at discussing aesthetics, and in some cases the technical and functional properties of an artist’s media in painting and sculpture. However, a lack of technical knowledge often led to both the capacities and the constraints of works that employed mechanical and electronic technologies being ignored. Until relatively recently, there was also no understanding whatsoever of imaginary media that were conceived at or beyond the limits of technical possibility in the era of their conception. As the media theorist Eric Kluitenberg observes, ‘the imaginaries of imaginary media tend to weave in and out of the purely imagined and the actually realized media machineries’ and thus the desires they would embody exceed the capacities and histories of ‘realized media machines’.1

Fig.1

Duncan Grant

Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound 1914

Gouache and watercolour on paper on canvas

279 x 4502 mm

Tate

© The estate of Duncan Grant

These limitations are relevant to my consideration of the technologies used, or imagined, in Duncan Grant’s Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound 1914 (fig.1), hereafter referred to as the Scroll. Much of our understanding of the work is informed by the artist’s thoughts some fifty years after its conception, and by the Tate curator charged with its conservation and interpretation, David Brown. Even the work’s official title was bestowed subsequent to its rediscovery in 1969. In the summer of 1914, Grant began work on an abstract mixed media work some 280 mm across and 4500 mm long using a collage of painted paper mounted on a canvas backing, which he intended to scroll in time with music. The Scroll was never exhibited before 1974, but Grant and his companion, the writer David Garnett, did show it to the writer D.H. Lawrence in 1915, who, in a letter to the influential patron Lady Ottoline Morrell, was unimpressed, describing the work as ‘very bad’ and dismissing the project: ‘We liked Duncan Grant very much. I really liked him. Tell him not to make silly experiments in the Futuristic line with bits of colour on moving paper.’2

Whether it was Lawrence’s patronising reaction, Grant’s flagging enthusiasm, a realisation of the technical problems he faced in fully exhibiting the work, or the effects of the First World War, the result was that the canvas was rolled up and kept in his studio in London. It remained there until the outbreak of the Second World War, when it was moved to Charleston House, Sussex, the country home of Grant and his partner Vanessa Bell. There it was stored in an attic where it remained until its rediscovery by Grant’s student amanuensis Simon Watney some thirty years later.

This essay argues that when the Tate Gallery made the decision to represent the Scroll as a film in 1974, the work was transformed in a way that ignored the historical and technical facts and discourses around which it was originally constituted.3 Certain assumptions made as part of the process to exhibit the work bore little relation to what was feasible sixty years earlier. This led to the eventual reconstruction of the work by the Tate Gallery using technologies and media concepts which were not available to Grant in 1914. Subsequent generations of art history, film and literature scholars, variously unfamiliar with the technologies and histories of painting, film and indeed performance have followed this lead, and the Scroll has come to be understood as a work that relates rather more to the history of film than to the history of painting.4 The decision to film the Scroll by tracking the camera across the static canvas was motivated by concerns relating to its conservation – it was thought that due to its age, it was too delicate to exhibit as a functional kinetic artwork. Regardless of its age, the way that the Scroll was constructed meant that it was always insufficiently robust for that purpose. Had the canvas been run by a mechanical mechanism in 1914, its collaged and painted surface would soon have fallen apart. Yet a consensus formed between the work’s re-emergence in 1969 and the Tate exhibition of 1974 that it was to be scrolled, or rather, tracked in time to the Adagio from J.S. Bach’s First Brandenburg Concerto, BWV1046. If this had been Grant’s original intention in 1914, then how did he envisage its practical realisation with the technology at his disposal?

The winding mechanism

The first practical challenge Grant had to solve in 1914 would be the means of winding the Scroll at a prescribed rate. Whether the movement was supposed to be human-powered through a geared hand-crank or automated with an electric or clockwork motor, the mechanism would need to store and release sufficient kinetic energy to scroll a heavy, four-and-a-half-metre long canvas. Yet if such a motor could be sourced, the structural integrity of the Scroll would have become quickly degraded, thanks largely to the delicate materials used in its construction. Was it therefore a work that Grant intended to be eventually destroyed through repeated use, anticipating pieces such as Suzanne and Marcel Duchamp’s Unhappy Readymade 1919, or the late-modernist vogue for ephemeral, auto-destructive art?5 There is neither direct nor anecdotal evidence to support this and so we must conclude that Grant as artist, or perhaps David Garnett as engineer, either lacked the necessary practical skills to fulfil their ambitions for the work, or that the Scroll was constructed for a different purpose that required a similar functionality, even though there is no direct evidence to support such a hypothesis.

As already stated, the bulk of our information regarding the purpose and function of the Scroll originates from the choices Grant made for the 1974 Tate Gallery film. The title, the prescribed tracking rate and the choice of music all date from this moment, and to unquestionably accept that Grant’s choices in 1974 were identical to his intentions in 1914 would be misguided. His recollection of the Scroll would have been distorted by time and coloured by his life experiences subsequent to that early period of his career. These are the recollections of a man in his mid-eighties, painting a portrait in time.

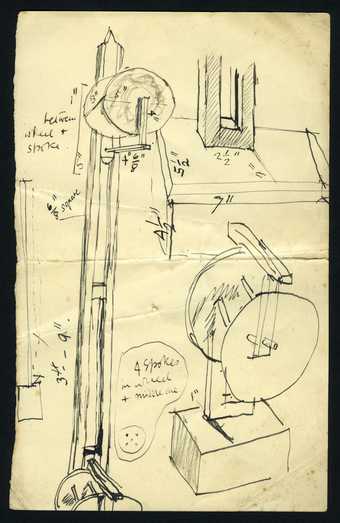

Fig.2

Duncan Grant

Sketch for a winding mechanism for the vertical operation of a version of Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound c.1913–14

Simon Watney Papers, Tate Archive TGA 20036/3

Given the shortcomings in the manufacture of the Scroll, and the seemingly insurmountable technical challenges in realising the work as a kinetic installation, it would be easy to dismiss it as an ambitious yet inherently flawed project, revived only through the application of refined technologies in 1974. However, an argument can be made that the Scroll was never intended to be exhibited publicly and that it should be placed within a domestic setting, along with the gramophone and the pianoforte, as an example of the Omega Workshops’ commercial decorative art.6 Along these lines, art historian Christopher Reed has observed that the work ‘belongs to the tradition of Bloomsbury’s subversive domesticity … rather than the tradition of modernist gallery and studio-based installation art’.7 Yet it seems inconceivable that the Scroll, with its dimensions of 279 x 4502 mm, could have been anything other than a piece of gallery-exhibited work. Can we then hypothesise that the Scroll was either a prototype or a production template from which copies of a reduced size could be produced? Grant’s 1914 sketch of a winding mechanism allowing for a scroll 76.5 mm (3 inches) across (fig.2) suggests that this mechanism might have been intended for a practical realisation of the Scroll. While there is no empirical evidence to support this, the practicalities of employing the Scroll in its original dimensions preclude its use in anything other than an exhibition of auto-destruction. We realised such a scaled-down model of the work for domestic use as part of this project.8

There has been speculation as to whether the winding mechanism as set down by Grant, or indeed a mechanism capable of manipulating the original scroll, would have been automated, its progression through the viewfinder governed by an electric or clockwork motor.9 Both kinds of motor were available and both had been used to power the turntable of a gramophone, although clockwork was by far the dominant engine in gramophones in 1914. As scientist and curator V.K. Chew points out:

The spring driven motor remained the only practical source of motive power for mass produced domestic instruments until the majority of households were connected to the public electricity supply mains and even then, the full advantages of the electrical drive were only realised when these mains supplied alternating current.10

There were electric motors available in 1914, and so it is not impossible that Grant envisaged an automated system to scroll the canvas. The most common form was the ‘induction’ motor, invented by Nikola Tesla in 1883. This design is powered by a single phrase 120/240 volt alternating current and today induction motors are commonly found in household appliances such as fridges and washing machines, and in electric cars. They operate most efficiently at high speed and can be governed by adjusting the electrical supply. However, the induction motor is best suited for applications that demand cycles typically well above 600 revolutions per minute (rpm), and so would not have been appropriate to power a winding mechanism for the Scroll, unless there was a sophisticated gearing mechanism to reduce the movement of the decorated surface to the point where its forms became distinct to the viewer. Given the discrepancy in these two speeds there would be considerable loads imposed both on the gearing mechanism and the driveshaft of the Tesla motor. The other electric motor available was the ‘synchronous’ motor, invented in the early 1870s and first demonstrated by the Gramme Company at the Vienna International Exhibition in 1873. The first commercial synchronous engine was released by Westinghouse in 1893.

As the energy scientist Vaclav Smil has noted, ‘The advantage of the synchronous motor is that it can operate at very low speeds and will maintain a fixed speed … Because its frequency is fixed, the motor speed does not vary no matter what the load or voltage of the line.’11 In 1914, a synchronous motor would have been the obvious choice to automate the progression of the Scroll, if indeed Grant ever envisaged such a process. In subsequent decades, synchronous motors were used to run gramophone turntables at the prescribed rates of forty-five, thirty-three and seventy-eight rpm. It would have been a fairly simple procedure to govern the rotation of a synchronous motor to fit a defined scroll rate decided by the artist. However, it would have been problematic to have used such an engine in this way. It would have had to have been a very substantial unit to scroll a canvas that was four and a half metres wide. This would not have been an insurmountable problem – the Westinghouse engine of 1893 was used to power an industrial ore crusher – but it is unlikely that an engine powerful enough to operate the Scroll would have been available to Grant in 1914. There would also have been precious few galleries, let alone homes, with the electrical resources to power it. Even if such a space could be found, the noise, especially the low bass frequencies generated by such a motor, would likely have drowned out all other sounds, including music, given the limited amplification of musical recording at the time.

Music and sound

Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound is an intriguing title insofar as it is both nominative and determinist. While not a typical work by Grant, it does have a typically empirical title, providing description rather than evocation.12 It does possess one distinction, in that it is the only work by Grant that includes a constituent not present on the canvas – ‘sound’. There is no evidence to confirm this was its title in 1914; indeed, there is no evidence the work had a title. Grant formally provided or consented to it sometime between 1969 and the work’s capture onto film at the Tate Gallery in 1974. It would be fascinating to know precisely when that was and what negotiation took place. If, after it was first unrolled in the garden on that summer afternoon at Charleston, Watney asked its name and Grant replied ‘Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound’, then it is credible that this was always the title – either explicitly so or, given Grant’s proclivity for providing prosaic titles for his artworks, implicit, unarticulated, yet inherently present. It is equally possible that Grant conceived of the title only after its rediscovery. This distinction is important because of the inclusion of the word ‘sound’ – was this ‘sound’ as defined in the first or final quarter of the twentieth century?

The lexicon of modernist aurality can often be obfuscating and contradictory. Our contemporary understanding of the word ‘sound’ is that it is the carrier of the message – the ‘sound’ of the factory floor or the ‘sound’ of music – perceived from a single point of observation. Moving closer to the source, a distinction can be made between different aural components and if, while straining to identify one component, its verisimilitude is subsumed by extraneous aural elements, then those other elements become the ‘ground’ that interferes with the signal message. ‘Sound’ therefore relates to both the objective delivery of aurality and the subjective reception of the message or ‘figure’.

In 1914 the term ‘sound’ was intrinsically linked to the production of music, and non-musical aural iterations were generally classified as ‘noise’ or ‘noises’. This is why Luigi Russolo’s highly influential futurist manifesto, where he advocated the creation of new instruments to evoke the modern landscape, was called L’Arte dei Rumori (The Art of Noises) (1913) and his new instruments, intonarumori (noise intoners). In this text, Russolo encapsulated the contemporary definition of the terms ‘sound’ and ‘noise’ when he stated, ‘Musical sound is too limited in its variety of timbres. The most complicated orchestras can be reduced to four or five classes of instruments different in timbres of sound: bowed instruments, metal winds, wood winds, and percussion. Thus, modern music flounders within this tiny circle, vainly striving to create new varieties of timbre.’ He stated further: ‘We must break out of this limited circle of sounds and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds.’ 13

Throughout the twentieth century, the means to store temporal aural elements grew appreciably from the gramophone technology of the late nineteenth century – electric signal amplification in 1925; optical sound tracks of the 1930s; magnetic tape in the 1950s; the digitisation of the analogue signal in the 1970s; and the digitalisation of the process of production, storage and playback in the 1990s. In the early twentieth century the printed score principally defined music as a physical artefact. Within this context, music is neither sound nor performance, but is stored data, to be decoded and converted to intoned sound through orchestral or individual performance. The score is the standard and performance, the variation, and therefore the object of music is made subject through human agency.14

In this sense ‘sound’ has nothing to do with the creation of music and everything to do with its manifestation within performance. Gramophone technology became another storage medium for ‘musical content’, yet it did not archive the score – the ‘music object’; rather, it archived the sound of the performed score, making the gramophone disc a ‘sound subject’. A physical disc, it could be argued, is a ‘sound object’, because like the score manuscript, it is a non-plastic form which is not subject to variation. This is because, like the frozen sounds in Gargantua and Pantagruel by the sixteenth-century French writer François Rabelais, it has bypassed the temporality of live performance and so is abstracted from the ‘instant’.15 However, variation is manifest through playback – the manufacture of the gramophone, the quality of the stylus, the acoustic properties of the playback space and the position and reception motivation of the listener. As such, the gramophone disc represents both the physical artefact, the object, and the variation of performance, the subject, within the context of repeated playback.

The capturing of sound

In the era when the Scroll was constructed, both popular and classical music genres were published in notated form.16 Gramophone recordings were regarded principally as a means of popularising contemporary songs. Indeed, often the gramophone recording of a popular song would not be commercially released until its sheet music sales had begun to fall.17 As music scholar Daniela Furini has pointed out:

At the time of emergence of recorded music, music publishers and instrument manufacturers were among the most influential institutions in the popular music industry: an analysis of advertisements in music magazines of the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s – such as the British Melody Maker or the American Billboard – suggests that sheet music and music instruments, not records, were the most heavily promoted musical commodities throughout the 1920s and 1930s.18

It was not until the late 1920s and early 1930s that gramophone disc sales would surpass sheet music sales by value, but prior to that, the public was more participative in its interaction with music. The middle classes purchased the sheet music for a popular piece to play on the pianoforte in their front parlour. In England, working class public houses were hotbeds of amateur recitals and the communal singing of songs popularised by stars of the variety theatre and music hall. Almost every pub had a piano and regular patron-musicians came equipped with banjos, squeeze boxes and ukuleles.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the establishment of national broadcast radio, the introduction of sound to the movies, and electrically recorded gramophone discs transformed audiences from the active participants of the past, to passive receivers of entertainment through commercial portals. The new portable, clockwork-powered gramophones and battery-operated portable radios replaced the guitars, banjos, squeeze boxes, violins and ukuleles at social events.19 Yet, for the first decades of the twentieth century, sheet music was the dominant form of music publishing and provided the most significant percentages of income for both publishers and composers.20

In 1914, discs were still perceived as novelty items, partly because there was no agreed commercial standard. It was possible to buy gramophones that played discs made of chocolate.21 The Apollo No.10 gramophone was driven by a hot air motor powered by methylated spirit. The inventor Henri Lioret, who later devised a cylinder with a celluloid surface which could be softened with hot water to make the recording, began his career installing small gramophones in toy dolls.22 Some companies employed different methods of disc manufacture that would only play on their machines, such as Thomas Edison’s Diamond Disc system.23 While the speed of the rotating disc, the rpm, was approximately 78 across the industry throughout the acoustic era of gramophone technology, this was not formally standardised until the electric motorisation of the turntable. In 1925, 78.26 rpm was chosen as a standard for motorized phonographs because it was suitable for most existing records, and was easily achieved using a standard 3600-rpm motor and 46-tooth gear.24

The sound quality of discs was also highly variable, usually because of the method of audio capture. The playback volume for an acoustic gramophone was less dependent upon the size of the amplifying horn and more on the location of the ‘performer’ in relation to the acoustic capture horn during the recording. There was a balance to be made between the vibrancy of the recording and the durability of the commercial disc. If the recording was loud and dynamic, the grooves cut into the disc would be too wide and the disc would wear out quickly.25 In 1911, His Master’s Voice (HMV) began conducting ‘wear tests’, where a performer was positioned at a variety of distances from the recording horn to sing the same short segment or phrase.26 It was decided that for commercial reasons the standard operational lifespan of a shellac disc should be fifty plays.27 Consequently, the position of the performer in relation to the capture horn was where the best sound was inscribed, while still allowing the disc to be played back fifty times before it became worn out. Ironically, the effect of standardisation in this era resulted in flatter, less dynamic and therefore less compelling recordings.

By 1974, when Brown tried to work out what Grant had wanted the work to do, this situation had changed considerably in terms of the creative and technological processes involved. The rapid development of recording and playback systems transformatively affected traditional and popular music, including the African American acoustic folk genre known as ‘Mississippi Delta Blues’.28 The electrification of the guitar shaped the music of itinerant performers like Lead Belly and Robert Johnson into a more structured and formalised style that came to be known as ‘Chicago Blues’. This was an urban, recital room, radio and recording studio ‘sound’, where the guitar and frequently the harmonica were played through an amplifier to the point of saturation, or even distortion, backed by a rhythm section comprising electric bass guitar and drums.29 Primitive dynamic mixing was established through the use of positioned microphones. The artists like Howling Wolf and Muddy Waters who established this form were part of the great migration of African Americans from the Southern states to the industrial north as a consequence of the more prevalent persecution and racial segregation in the South.30

The significance of this is that the original creative methodologies of composition and arrangement, through improvisation and repetition, remain largely unchanged. Unlike classical music, the simultaneity of compositional and recording processes encapsulated both archival and performative elements of the work.31 The definition of the term ‘sound’ within the arts had also evolved throughout this period. The composer Edgard Varèse regarded his music as ‘organised sound’ and stated that ‘to stubbornly conditioned ears, anything new in music has always been called noise’ and he posed the question, ‘what is music but organised noises?’32 The composer John Cage, influenced by Varèse and Luigi Russolo, also regarded his compositional work as ‘the organisation of sounds’; an echo of Russolo’s ‘network of noises’.33 Within this framework, the term ‘sound’ was undergoing a transformative process to encompass all discernible auditory emanations. So, while the concept of noise remained intact, the modernist concept of ‘noises’ had, by 1969, been largely subsumed within our notion of ‘sounds’.

Yet in 1914, within the environs of the concert hall, recital room or theatre stage, ‘sound’ referred to the delivery of music and speech, when received by the audience or observer. As the media historian Douglas Kahn observes, ‘In terms of universality of all sound during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the strains of neo-Pythagoreanism were detectable in two main places: synthetic systems and Western art music … Neo-Pythagoreanism was required to invoke the universe and its universality through limited auditive means, through privileged forms of utterance.’34 Thus, all sound was not only reduced to an anthropocentric determination; it was further reduced by being limited to what humans uttered (spoke, performed) within elite cultural practices and by excluding what humans heard apart from those utterances – what they heard of the rest of the world.’35

While there is no evidence that Grant had the title Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound in mind in 1914, I argue that the employment of descriptive titles for his artworks is indicative of a particular working method. This indicates that his intention was always to create an abstract kinetic painting that could be scrolled while music was played on a gramophone. I argue that Duncan Grant in 1974 was using the term ‘sound’ as it was generally understood in 1914, meaning the neo-Pythagorean privileged and sacred concept of the word, as a manifestation of music. Had he intended to include non-musical ‘sounds’, perhaps inspired by futurism, as Lawrence alleged in his dismissal of Grant’s project, then Duncan Grant in 1914 would most likely have called his work ‘Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Noises’.

Music and the filmic exhibition of the Scroll

The Tate Gallery’s film of the work was made under the direction of Christopher Mason in 1974, by unrolling the canvas and recording it by tracking a video camera over it at varied but consistent speeds within each take, and in a fixed orientation, mounted on an improvised rig. The video tape of one of those recordings, selected by the artist, was subsequently transferred to film. The film camera did not ‘pan’ across the scroll. Panning is when the camera is moved across the horizontal axis from a fixed position. To have employed this technique would have resulted in an increasing optical distortion the further the camera is panned from the centre of the Scroll. The technique employed would have been ‘tracking’, where the camera’s focal length and ninety-degree angle remain fixed, while the body of the camera is moved at a prescribed rate along the length of the Scroll. The camera would have been attached to a ‘dolly’ placed on a track. The film misrepresents the original work in terms of scale and materiality: it becomes a large, disembodied moving pattern of light on a wall, which was far larger than the light field thrown by most projectors of 1914, and something that might be viewed in a proscenium arch theatre.

Grant had the final say on the decisions made for the filming, according to a report published by the Tate Gallery in 1975:

The painting was then filmed on video tape at various speeds and these were projected to the artist, accompanied by a recording of the chosen music, on 5 June 1974. The artist selected as most nearly according to his concept a speed of movement at which, by chance, the duration of the painting’s complete movement, once, coincided with that of the chosen slow movement by Bach (approximately 4 minutes 20 seconds).36

While this is indicative of an entirely automated system, it also suggests that the pace of the Scroll was linked to the duration of the music accompanying it, rather than the other way around. In 1974, the Adagio from Bach’s First Brandenburg Concerto was Grant’s expressed preference for a gallery screening where the physical manipulation of the Scroll through human agency was impossible. In this iteration, the Scroll was a work of passive reception rather than active participation and so was in keeping with 1970s film installation practices.37 The Tate Gallery film is an illustration of how widespread scholarly trends in art history and film studies in the 1970s contributed to misconceptions of how a kinetic work might have been realised in 1914. The kinetic property of the Scroll was inherent within the movement of the fabric, not through the persistence of vision of the movie camera. But in an era in which modernism was understood as characterised by medium-specific formalism, the possibility of mixed-media works with a functionality beyond the solely aesthetic was seemingly set aside and effectively regarded as inconsequential. As a result, the diversity of technological experimentation contained within modernist artworks was retrospectively siloed into contemporaneous categories, which either did not exist in the era when the artwork was created, or which they were actively seeking to transcend. It would be a mistake, therefore, to regard the Scroll as a work which somehow anticipated the emergence of film, as that medium in 1914 had already existed for over two decades.

Returning to the choice of music for the film, it is unlikely that Adagio from Bach’s First Brandenburg Concerto was Grant’s preference in 1914, not least because it had not been recorded. Little classical music had been committed to disc or cylinder. As Christopher Townsend has noted:

Simon Watney, in a conversation in April 2012 told me that Grant fixed on Bach as appropriate music only after the rediscovery of the work, when the Tate wanted to turn it into a film, and that in 1914 he had wanted to use recordings of more contemporary music. ‘Contemporary’ here should not necessarily be taken to mean ‘classical’, since recordings of Schoenberg and his peers were thin on the ground in 1914. Grant might well have been referring to popular music.38

The gramophone music catalogues printed between 1898 and 1914 support this observation. There were few contemporary ‘classical’ works available: recordings of Bach were thin on the ground too. The majority of the discs on offer throughout this period were excerpts from popular operas and operettas, band marches, popular sentimental songs, speech recordings and solo whistling.39 And while gramophone and phonograph recordings of Bach music were available, they were very scarce, and they were not orchestral.40 Indeed, the first commercial recording of the First Brandenburg Concerto (Brunswick 30135/30136), performed by the London Chamber Orchestra and conducted by Anthony Bernard, was released only in 1929, four years into the electrical era.41 Grant had never heard a recording of the Brandenberg Concertos when he made the Scroll.

Recording full orchestral works before the electrification of the input signal was highly problematic. Analogue recording requires that the audible signal be condensed to the point that it is of sufficient amplitude to allow the stylus to cut a groove into the master disc or cylinder. In the acoustic era, this was achieved through the positioning of performers around a condensing horn. In electrical recording, which became standard in 1925, the music is captured using a condenser microphone, also known as a transducer, which converted the vibrations into an electrical signal, which was amplified and sent to another transducer, also called a stylus, which cut the grooves into the disc. This system provided a much more enhanced fidelity. The introduction of the electrically powered microphone allowed for a far greater dynamic range and soon a number of microphones could be attached to a mixing console. These microphones, positioned carefully within the performance space, could be manipulated to alter the overall balance of the recording as it was being made. Solo instruments could be raised in level, whole orchestral sections could be backgrounded and consequently the direct, or as Edison would have put it, the ‘pure’ link between the performance and the recording was removed.42 However, ‘mixing’ the input signal allowed for a greater resolution in the recording which, with the more sophisticated domestic playback machines with electrical amplification, enabled more complicated orchestral arrangements for compositions like Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos to be commercially released.

Fig.3

Edward Elgar conducting a recording session in 1914

Acoustic recordings were primitive by comparison. The performer(s) would gather around a large recording horn, arranged according to the natural amplitude of their instruments, as in the photograph of Edward Elgar conducting a recording session in 1914 (fig.3), where the string section is positioned far closer than the brass and woodwind sections.43 The only mixing would have been kinetic, where a performer would physically move closer to the horn in order to foreground a solo sequence. Resolution was a problem because of the inability to lift or lower the input signal and the poor dynamic range meant that too much instrumentation resulted in indistinguishable noise. Consequently, orchestral recordings were made with a cut down orchestra.

The role of the body

While the decision to film the Scroll was informed by its fragile condition, it is interesting that in 1974 the Tate Gallery appears to have conducted no research regarding the availability of recorded music in 1914. One might hypothesise that this was because the Scroll was an uncompleted work created by a living artist and the filming in 1974 was the completion of that work, as directed by that artist. This is not an unreasonable position to take, yet had Watney discovered the Scroll after Grant’s death, would Tate have been so presumptuous with the work’s historical accuracy?

Grant seems to have planned that the canvas should be fitted into a winding mechanism, perhaps turned by hand, necessarily placed within a case, and viewed in motion through an aperture to the accompaniment of gramophone records.44 This account is indicative of a considerably more personal and interactive relationship with the artwork. The body is the missing component of the Tate exhibition and this essay rejects the assertion that the scrolling mechanism was to be self-governing, through the agency of a sequential engine. As Townsend states, ‘Indeed, there are meant to be figures in “the Scroll”: they are real bodies, operating the device, moving in harmony with the recorded music and the evolution of its abstract forms. To some degree, the body mirrors the movement of those forms.’45

There are variables that occur with human interaction. The music would be the sole choice of the human agent operating the scroll mechanism and would not have been selected principally for its sympathetic support of a prescribed scrolling rate. It is not the music that is governed by the progression of the Scroll, but the reverse.

In drawing this conclusion, one should also consider just what the progression rate of the Scroll might have been for the 1974 film, depending on what recording was chosen. As this essay confirms, there were no recordings made of the Adagio for the First Brandenburg Concerto before, at the very earliest, 1929, and yet the recordings made subsequent to that date differ wildly in terms of duration, so the prescribed progression rate of the Scroll would have differed depending on what recorded version was chosen. In addition, as we showed in our introduction, there are huge differences in the length of the movement, depending on the decisions of the conductor and the growing adoption from the 1960s of period performance practices.46 There is an argument to be made that Tate’s choice, the 1966 recording by the Württemberg Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Jürg Farber, was made for financial reasons. This recording would likely have been much cheaper to license than, for example, Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s Concentus Musicus Wein (for Das Alte Werk, 1964) or Otto Klemperer and the Philharmonia Orchestra (for EMI, 1962).

Perhaps, ultimately, the choices made by the Tate Gallery in 1974 were predominantly centred in a pragmatism which encapsulated the notion that they were completists, working in the ‘now’ in realising an uncompleted and unexhibited artwork by a living artist and in consultation with that artist. What is apparent from reconceptualisation to realisation is that no significant thought was ever given to what had been achievable in 1914 other than through the recollections of the octogenarian artist fifty years after the artwork had first been conceived. What the Tate Gallery did in 1974 was to imagine and then project the work (literally) using the technologies of the present rather than those available to the artist when it was made.