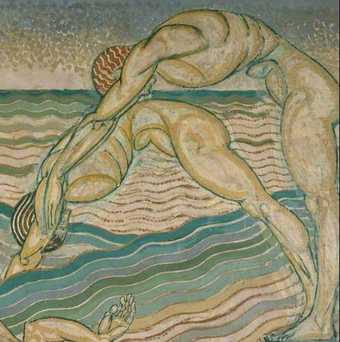

Fig.1

Duncan Grant

Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound 1914

Gouache and watercolour on paper on canvas

279 x 4502 mm

Tate

© The estate of Duncan Grant

In this essay I trace the origins of Duncan Grant’s Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound 1914 (fig.1) in relationship to the paintings that he made from 1910 onwards, and to the designs that he and Vanessa Bell made for Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops between 1912 and 1914. In addition, I examine Grant’s work in relation to the philosophical ideas circulating in the Bloomsbury movement. I consider these practices and ideas alongside other developments in European modernism which Grant could have encountered. In particular, I show how these works, and this thought, share Grant’s interest in kinesis and embodiment. In our introduction to this project, Alexandra Bickley Trott, Rhys Davies and I showed that however important it is to the histories of modernist culture as a painting, Tate’s surviving canvas could be neither kinetic nor accompanied by sound – at least not with 1914 technologies.1 The model of a projected, finished version of the work based upon the real capacities of period technologies and Grant’s own sketch for a winding device suggests that to be both kinetic and audible the work needed to be scaled down, to such an extent that its obvious home would be the home. This would accord both with the influence of Chinese handscrolls on the work – unrolled in an intimate environment and visible only to two or three viewers at a time – and with the large numbers of designs for domestic use that Grant and Bell made for the Omega. I show here that this interest in kinesis and intimacy is accompanied by profound formal affinities between some of those Omega designs and the rhythmic patterning of the Scroll, as the work has become known.

The essay has a trilateral, intersecting argument, rather than a linear development, with those three vectors coming together in an interpretation of the Scroll as intended domestic object of aesthetic ‘entertainment’. Two elements demonstrate the aesthetic and the philosophical influences behind the abstracted, rhythmic forms in the work; they detail Grant’s interest in and knowledge of repeated and varying forms from within both classical and contemporary art, and show how the manifestation of rhythmic form in the Scroll relates to the arguments posed by Bertrand Russell, Karin Costelloe and Roger Fry about the human experience of temporal and spatial continuity. It is this broadly analytical Cantabrigian school of thought which emerged in the late nineteenth century that provides much of the stimulus, and locus, for ideas within the Bloomsbury Group of writers and artists, which included Grant and Bell. A third strand demonstrates the degree to which the Scroll, and Grant and Bell’s practice for the Omega, fits into a wider tradition of intimacy and kinesis in European modernist practices in the years before and immediately after the First World War. This tradition is often understood as ‘cinematic’ through mistaken readings of its works’ forms, contents and conceptual bases. Whether Grant directly encountered the manifestations of this culture is moot – knowledge or direct experience of all of them were certainly available. What all these projects attempt, however, is the reconciliation of the subjective sense of being with the fragmentary, discontinuous experience of time and space in industrial modernity, through the participation of the body in media-suffused spaces.

Grant’s encounters with rhythmic form in painting

Fig.2

Henri Matisse

The Dance 1909–10

La Danse

Oil on canvas

2600 x 3910 mm

State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

© Succession H. Matisse

Fig.3

Henri Matisse

The Dance (I) 1909

La Danse (I)

Oil on canvas

2597 x 3901 mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2020 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Grant saw a version of Henri Matisse’s The Dance 1909–10 (fig.2), in the early summer of 1911, during a studio visit facilitated by a family friend, the French painter Simon Bussy. The painting is notable for Matisse’s effective union of the five separate, naked bodies of the dancers into a single entity through formal devices. Although the figures are caught in a single moment, the painting succeeds in conveying a profound sense of rhythm and movement; it both freezes and extends temporality. There is a circular flow of movement at the centre of the painting created by the outspread, linked arms of the dancers; though we should note that much of the energy in this circle comes from its broken-ness, as the left hand of the female figure in the foreground reaches towards, but does not quite touch, the outstretched right hand of a male companion. In an earlier study (fig.3) this gap is far wider and the sense of energy is accordingly dissipated. Matisse accentuates the relationship between the dancers through formal assonance between curves of buttocks, thighs and calves, and the arch of backs. Having established depth relation in the ordering of figures, however, Matisse also uses this assonance to completely flatten the perspectival field: thus, the left arm of the male figure at the left of the canvas reaches across but not into the picture in order to grasp the right hand of the female dancer at the back of the circle.

Grant’s first response to The Dance was to paint his own version, or rather two versions: Dancers c.1910–11 (fig.4) and Dancers 1912. If Grant’s dancers lack the corybantic frenzy found in Matisse’s final version, the clothing and the ridged hair of the central figure in his first study point to other influences that he encountered in the spring and summer of 1911. These sources would become obvious in Grant’s Bathing 1911 (fig.5), commissioned for the dining room of the Borough Polytechnic Institute, London. The most common observation of the time was that Grant effectively cited Byzantine or Byzantine-influenced art: the ribbons of colour that represent the waves are nearly direct appropriations of twelfth century mosaics in the cathedral of Santa Maria la Nuova in Monreale, Sicily, which Grant had visited in spring 1911. However, the ridged hair of one swimmer may originate in Grant’s close observation of Greek art in Sicily or the classicist Jane Harrison’s comment – in a volume that Grant had read in 1908 – that athletes of the seventh century BC ‘wore their hair long, and plastered, and plaited it into shapes’.2 The swimmers in Bathing, drawn from the antique, are figured within the new conventions of modernism through the repetition and development of form in different positions across the picture plane, thus extending the conventional, singular temporality of the painting.3

Fig.6

Duncan Grant

Bathing, detail

© Tate

There are seven figures in Bathing, but comparison of the hairstyles suggests that there are only two bodies. If we begin at the right side of the picture – the same side, incidentally, from which we read the displacements and transpositions of abstract form in the Scroll – we see two naked men: one with his hair ridged longitudinally; the other’s ridged horizontally, with a crinkled effect (fig.6). The two figures are, in the first position, posed side by side in the act of diving from a platform so that they might be read as the same figure in fractionally different stages of movement – in the manner of one of the photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s sequential studies.4 However, the hair allows us to differentiate what might be read as formal similarity. We thus have two different natural forms in space, but existing in the same moment of time. We may then follow the figure with the longitudinal plaits in three subsequent positions across the canvas: first swimming, then holding onto the side of a boat, then climbing into it. The figure with the horizontally ridged hair reappears most obviously in a swimming figure in the left foreground. Between this and the diver is another swimmer, the head rotated so that the hair cannot be seen, but which might be understood as the same figure in an intervening state of movement.5

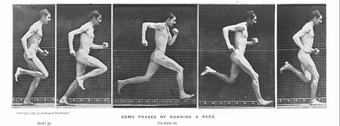

Fig.7

Eadweard Muybridge

Some Phases of Running a Race, from Eadweard Muybridge, The Human Figure in Motion, London 1878

Grant thus does two things in Bathing: he establishes difference and displacement of forms in the same instant, then loosely unfolds a temporal sequence of movement, held in fixed instants, across the canvas. If the first position has something of the systemic property of a Muybridge photo, what follows is not regular. Bathing does not confine its bodies’ movement within the rigid temporal and spatial matrix that Muybridge uses (fig.7). While broaching the kineticism of bodies within a single space, it is thus also unlike film, which in its absolute ordering of time and space – effectively turning space into time at the rate of sixteen to eighteen frames per second – further develops Muybridge’s principle of momentarily arresting movement.

Fig.8

Fernand Léger

Nude Figures in the Forest 1909–11

Nus dans la forêt

Oil on canvas

1205 x 1705 mm

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

In a remark that resonates with the writer D.H. Lawrence’s sceptical observations about the Scroll discussed in our introduction, art historian Richard Cork has remarked that the sequential figuration in Bathing is ‘oddly comparable with the Futurists’ interest in bringing together the various consecutive stages of an action’ – what those artists termed simultaneità.6 At the same time, Cork suggests that futurism was an unlikely source of influence. The art historian Simon Watney, among others, has pointed out that Grant was fundamentally hostile to futurism, perhaps as much for its temper as its technique. Furthermore, simultaneità does not so dramatically separate its repeated, displaced figures in the way that Grant does in Bathing. Grant could have seen very little futurist painting before he painted Bathing, if he saw any at all: he was not in Paris at the time of the group’s participation in either the Salon d’Automne in October and November 1909 or the Salon des Indépendants in March and April 1910. The first group show in London to include futurist work was at the Sackville Gallery in early 1912.7 However, the visit to Paris in 1911 would have given Grant the opportunity to explore the work of other modernists who were challenged by a direct encounter with futurism, and who similarly proceeded from the conceptual basis of fluxive, temporal-spatial transition found in the writings of the philosopher Henri Bergson. These were the ‘Puteaux cubists’, a group of young French artists working in the wake of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Juan Gris, and included Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger and Fernand Léger. They showed collectively in room forty-one of the Salon des Indépendants of 1911, which ran from 21 April to 13 June. Léger’s abstraction of forms from nature into rhythmically composed facets, exemplified by Nude Figures in the Forest 1909–11 (fig.8), is especially notable.

Fig.9

Frantisek Kupka

Woman Picking Flowers 1910–11

Femme cueillant des fleurs

Pastel, watercolour and graphite on paper

450 x 450 mm

Centre Pompidou, Paris

© ADAGP, Paris

We know that Grant first met Léger through Gertrude Stein in early 1914.8 Also among the artists exhibited in room forty-one was the Czech émigré František Kupka. Along with Marcel Duchamp and Jacques Villon (both also included in the Salon’s hang of the Puteaux group), Kupka was one of the first modernist painters to explore the implications of the chrono-photography of Muybridge and Étienne Jules Marey within the seemingly static and closed space of the pictorial framework.9 Kupka’s five pastel studies Woman Picking Flowers 1909–10 are read by curator Margit Rowell and others as profoundly influenced by chrono-photography. One of the studies (fig.9) includes figures that are strikingly similar, formally, to the first position and displacement of those in Bathing. Grant could not have known these works by Kupka, which only became public in the early 1960s. We might conclude that rather than being directly influenced by futurism, Bathing is affected by the ‘rhythmic’ disintegration of the figure into space, through formal rotation and displacement which he could have seen in the Puteaux cubists’ response to futurism. Like Kupka and several other European artists, Bathing was also clearly affected by the widely disseminated chrono-photographs of Muybridge, whose studies of the human figure were published in a popular edition in London in 1901.10 Kupka’s understanding of the potential relationships between painting and music, which became apparent in paintings such as Amorpha, Fugue in Two Colours 1912 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), would also have been of interest to Grant, given the influential ideas of Roger Fry that I discuss below. Nor, given its profound influence upon Grant, should we overlook that Kupka found the basis for that synaesthetic analogy within classical Greek art.11

Fig.10

Gino Severini

The Boulevard 1910–11

Oil on canvas

635 x 915 mm

Estorick Collection, London

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2020

By the time he made the Scroll, however, Grant undoubtedly had seen futurist painting, probably beginning with the Sackville show. Gino Severini’s Blue Dancer 1912 (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York), which Alexandra Bickley Trott shows to be an influence on Grant’s portrait of Lady Morrell, was included in Severini’s solo show at Marlborough Gallery in spring 1913.12 That exhibition also included overtly ‘simultaneist’ paintings such as The Boulevard 1910–11 (fig.10), in which a limited number of bodies are repeated across the canvas in minimally different stages of movement, but in which the differing vectors of the figures’ movement are used to fragment the perspectival view and create abstract fields of colour in the intervals between them. It is that process of abstraction which creates the sensation of rhythmic movement in the painting, while at the same time flattening its pictorial field and shattering any mimetic relationship to its subject, such as would characterise photography and film.

Walter Sickert, a painter probably even less likely than Grant to endorse futurism, did precisely that in his review of the Sackville show, demonstrating the degree to which the movement influenced British art from 1912 onwards.13 F.T. Marinetti, the leader of the futurist movement, visited London to help promote the Sackville show, delivering a lecture at the Bechstein Hall in Wigmore Street on 20 March 1913. In September 1913 the entirety of the influential literary magazine Poetry and Drama was devoted to the futurists: it included translations of futurist poetry and several of the movement’s important manifestos on art. The critic Frank Rutter’s Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition at Doré Gallery, running from October 1913 to January 1914, included Severini alongside a selection of Puteaux cubists, and the Doré followed this with a specifically futurist group show in April and May 1914. This would include not only paintings, but ‘Rumoriste’ (‘noise’) concerts in the gallery featuring compositions by Luigi Russolo. Furthermore, Marinetti lectured in London at the Coliseum Music Hall over six days in June 1914 (15–21 June), prefacing a series of concerts of futurist music by Aldo Buzzi, Ugo Piatti and Russolo. Although Marinetti delivered his perorations in French – he did not speak English – this would not have greatly hampered Grant’s understanding of the Italian’s themes. Given Marinetti’s talent for publicity and the extensive discourses within the London art scene that surrounded these lectures in 1912 and 1914, it is likely that Grant attended at least one of them. Furthermore, the association between painting and music that futurism promoted seems to me an important and so far neglected influence on the sudden emergence of that idea within Grant’s work.

Intimacy and kinesis in modernist projects

I turn now to some of the ways in which modernism experimented with bodily kinesis before the First World War, through the rhythmic articulation of abstract form and in intimate environments. We should note that intimacy here does not always equate to domesticity, but rather to a close engagement between the spectator and the artwork. This constitutes a profound challenge to the traditional Western notion (after the early modern era) of spectatorship as distanced, disembodied and objective, with a complete grasp of the visualised object – this is, of course, both the epistemic and ontological basis of cinema. By contrast, intimacy renders the spectator a participant, emphasises embodiment and establishes a dynamic relationship between audience and artwork; it also limits the field of vision. These four characteristics are recognisable in many of Grant and Bell’s projects for the Omega Workshops, and also in the Scroll, once we understand the transformations necessary to render it both kinetic and audible. I stress intimacy here because I want to challenge any notion of the Scroll as cinematic – distanced, disembodied spectatorship that privileges external, overarching perception is anathematic to the conception of all the works discussed here. All of them depend upon bodies, on physical intimacy and on haptic, sensory experience.

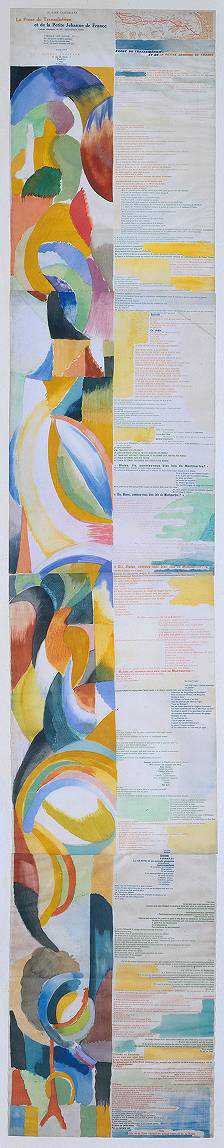

Fig.11

Blaise Cendrars and Sonia Delaunay-Terk

The Trans-Siberian Prose of Little Joan of France 1913

La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France

Watercolour and relief print on parchment

1956 x 356 mm

Tate

© Reserved

I attend particularly to prominent projects in Parisian modernism, concentrating on the work of Sonia Delaunay-Terk. Futurism engendered a number of related experiments in media-saturated, sensory environments, not least those of the Ginnani-Corradini brothers in Florence, beginning in 1910.14 However, it seems as though Grant primarily used Italy as a resource for its historical materials: his encounter with Italian modernism likely came only with its exhibitions in London from 1912 onwards, and it was not until the Doré show of 1913–14 that these included any performative element. By contrast, Grant felt at home in Paris, having studied and exhibited there, and at ease in the language. Simon Bussy’s patronage, along with Fry’s connections to artists, galleries and collectors, meant that he could engage directly with the Parisian avant-garde. The organisation of the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in autumn 1912 allowed Fry to establish personal connections with both Gertrude Stein, a major collector, and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, cubism’s leading gallerist. In the week before that show opened, in Fry’s company, Grant met Picasso for the first time, in Paris.15 Commissioned to work on set and costume design for a performance of Twelfth Night by the theatre director Jacques Copeau, whom he had also met through Fry in 1912, Grant spent most of January, February and March 1914 in Paris, and returned in May. While we have no clear evidence that he knew members of their networks, nor that he attended the best-known performance of Blaise Cendrars and Sonia Delaunay-Terk’s The Trans-Siberian Prose of Little Joan of France 1913 (fig.11), we do know that Grant was in Paris on 24 February 1914 when it took place. Furthermore, editions of the physical work, a two-metre-long strip that could only be read when completely unfolded, had been exhibited widely in late 1913, including in Paris (at the Salon d’Automne) and in London, giving Grant the opportunity to see it.16

While it is often claimed as a ‘simultaneous’ work, the simultaneity of The Trans-Siberian Prose derives from its intercalation of text and image. The text actually follows a linear narrative development, with that line being quite narrowly defined as the track of the trains between Moscow and Paris which the poet and his young companion, Jehanne (Joan), traverse.17 This is also the timeline of the poem’s recitation. The poem, however, is not all there is: it is accompanied by largely abstract designs by Delaunay-Terk that occupy the entire left half of the parchment and intercalate with Cendrars’ text through the use of blocks and slivers of colour derived from the same palette. As Katherine Shingler has shown, there is a strong, close relationship between text and visual form without that form being illustrative – with the exception of the Eiffel Tower at the very bottom of the parchment.18 The transitions between, and repetition of, these colours suggest daylight and night-time, giving the poem a duration of three days.19 The abstract painting is thus endowed with a temporal dimension: that temporality is reinforced by Delaunay-Terk’s use of repetition and displacement to create the impression of movement in abstract form. An essential motif in the linear progression of the design is the difference between separated sets of multi-coloured arcs, with each colour component sharing a single foundation point from which varying rotation produces spatial displacement. If this seems familiar, it is what Grant does at times with the sets of coloured rectangles in the Scroll, as we established in our introduction.20 Delaunay also rotates some of her sets along a longitudinal axis to effectively produce a circle with different colours grouped in either half. Grant therefore has an accessible model, after autumn 1913, that parallels – perhaps rather than directly influences – his ideas about sequence and temporal development across the canvas in Bathing, with the significant difference that Delaunay-Terk achieves this in the abstract. Furthermore, like other works by Delaunay-Terk to which I will shortly attend, The Trans-Siberian Prose solicits corporeal intimacy.

The reading of The Trans-Siberian Prose on 24 February 1914 was part of the Montjoie exhibition, organised by that journal’s influential editor, Ricciotto Canudo, who was a close friend of Picasso. The reader was the actress Lucy Wilhelm; the poem was hung on the wall, and must therefore, given the structural folds in the parchment, have been completely unfolded and static at the beginning of the reading. Initially, Wilhelm stood on a chair to read the lines at the top of the sheet, which were near the ceiling. To read the final stanzas at the bottom she was seated and bent double.21 The font and point of Cendrars’s text vary considerably across the length of the poem, as do its colour and tone. It simply cannot be read at a distance – some characters are as small as nine point; any reading solicits an embodied kineticism through the traversal of the work by an engaged participant and definitively not by a spectator. The film theorist Ian Christie has described The Trans-Siberian Prose as ‘precociously cinematic’.22 Yet it does not, in 1913, anticipate cinema, which was in existence since 1895. Nor do image or text move, nor would the text be legible. There is absolutely nothing about The Trans-Siberian Prose that is cinematic. Indeed, the audience at the Montjoie exhibition could hardly have seen the work, let alone read the text, because for most of the performance Wilhelm’s body would have blocked their view. Grant’s Scroll, of course, had a different kineticism, one inherent to the material form of the work rather than the body of the performer. It was, however, intended to be presented to an audience which was profoundly limited by that material form – a tiny viewing window – through partial, sequential disclosure. In presenting the Scroll as a film in the 1970s, Tate committed similar solecisms to Christie with The Trans-Siberian Prose, fundamentally misunderstanding the work in both conception and form. While there are differences from Grant’s project, what Cendrars and Delaunay-Terk do with the Trans-Siberian Prose also has parallels with the carpets designed by Grant and Vanessa Bell for the Omega Workshops. These designs, as I show below, have a fundamental formal and conceptual relationship to the Scroll. In them the essential kinetic property of the work derives from the movement of a participant walking over ‘a painting’: that is, the body traverses the artwork, and effect derives from the haptic relationship of subject and object.

While Delaunay-Terk made a number of obviously intimate domestic objects, such as blankets, that utilised similar abstract forms to those found in The Trans-Siberian Prose, I want to introduce another project – her clothing design – that for its kinetic property actually depended on the participant remaining static, even as they were, in effect, the embodied artwork. The use of clothing allowed Delaunay-Terk to treat the body as fragmentary and mobile and to similarly understand that as the subjectively experienced condition of the space and time inhabited by the body. Delaunay-Terk’s ‘simultaneous’ costumes were made specifically for her and her husband Robert to wear to the Bal Bullier nightclub. However, as Apollinaire observed, the Delaunays did not dance; instead, they sat near to the orchestra.23 In doing this, Delaunay-Terk sought to coordinate more effectively the rhythms of the orchestra with the formal patterning of the dress: it was not necessary to dance in the outfit; it reflected and responded to the milieu as an object in itself. Delaunay-Terk reinforced this idea when she later spoke of the range of colours in her dress as gammes or musical scales.24 The dress did Delaunay-Terk’s dancing for her – it engaged in a rhythmic action that dissolved the body in space and made apparent a modern, syncopated subject in harmonic (or dissonant) relationship with its milieu. The dress was a kind of screen for ‘visual music’; a static surface capable of producing extended kinetic relationships between visual and aural patterns. A similar principle, without the music, might be seen as being worked through in the fabrics produced for Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops: the linen Margery 1913, for example, was used both for curtains (part of a static environment that the body traverses) and tunics (an embodied element that moves through a static environment).25 A charming photograph in the Illustrated London News of 24 October 1915 shows Nina Hamnett and Winifred Gill of the Omega wearing clothing that effectively extends to the body, and renders kinetic, the art both on the walls and the domestic objects that surround them.26

My argument here is not that Grant necessarily met Delaunay-Terk or Cendrars, nor that he even necessarily saw the work – though he had opportunity to see The Trans-Siberian Prose in 1913 and witness its performance in Paris in 1914. Nor do I suggest that Grant and Delaunay-Terk necessarily shared similar conceptual premises in making these works – indeed, in the next section I shall highlight some of their differences. Rather, I suggest that within the Parisian avant-garde of 1913–14 – to which Grant had access, with which he had no little familiarity, and about which, during early spring 1914, he could read almost as matter of routine – there were a number of projects that involved kineticism, abstraction and intimacy that he could compare with his own ideas and practice. To Delaunay-Terk’s endeavours we might add, for example, those of the poet and dramatist Henri-Martin Barzun, whose widely disseminated conception of simultaneity influenced Puteaux cubism, orphism and futurism.27 The original manuscript books for Barzun’s Terrestrial Tragedy (1908–14), a choric, multi-part performance poem related to transforming, abstract colours, were exhibited in Paris during 1913–14.28

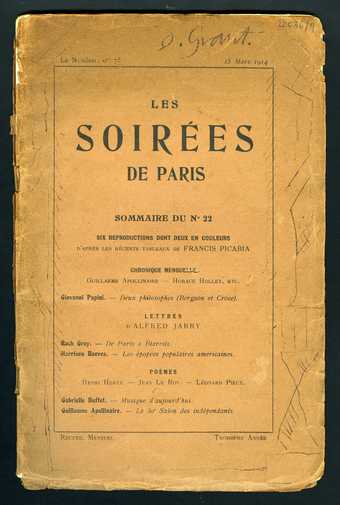

Given Grant’s familiarity with Paris and his access to its avant-garde through Bussy, Fry and Stein, he is likely to have been at least aware of some of these enterprises. We know that Grant purchased the journal Les Soirées de Paris in the spring of 1914: as I show in the concluding section to this project, he actually used the March/April issue to sketch ideas for abstract designs.29 While in Paris might he not also have read Mercure de France and L’Intransigeant? If he did, he would have encountered Apollinaire’s commentary on Delaunay-Terk’s ‘simultaneous’ dress and the review of Wilhelm’s performance of The Trans-Siberian Prose. Furthermore, as one of the key artists working with the Omega, by 1914 he would have been wholly aware of, if not one of the initiators of, the intercalation of the kinetic into the domestic space through the use of the body clothed in modernist, abstract painting. Grant also almost certainly encountered the most notably ‘cinematic’ of French modernist art projects, albeit in graphic, non-cinematic form. This was Coloured Rhythm (Le Rythme coloré) by the expatriate Russian painter Léopold Survage. The most often noted publication of the ideas behind this work was in the July/August 1914 issue of Les Soirées de Paris, post-dating Grant’s work on the Scroll. However, in the Salon des Indépendents of March 1914, Survage showed three sequences of his drawings for what would eventually be proposed as an abstract, animated film.30 Grant had the opportunity to see the Salon while he was working on sets and costumes for Copeau. Again, the sketch on the verso of the London Joint Stock Bank letter from early 1914 suggests that Grant was already having similar ideas about the transitions of form and colour over time, but seeing Survage’s work would have reinforced them. Furthermore, in March 1914 Survage had not necessarily then conceived his project as having a filmic outcome – its movement then may have been intended as kinetic rather than cinematic. In late June 1914, Survage made a deposition of his idea to the Académie des sciences de Paris (effectively patenting it); it speaks of real movement within abstract painting, but projection is nowhere mentioned.31

Bloomsbury’s philosophy of the time–space continuum

I now examine the theoretical concepts concerning the movement of forms in time and space to which Grant was exposed before 1914, and the ways in which he might be said to handle those ideas in his art. It is at this point that we might want to distinguish the conceptual parameters of Bloomsbury’s practice from that of the Parisian avant-garde, and indeed from most of European modernism. A significant influence on the intellectuals of the Bloomsbury Group was the analytical philosophy emerging from Cambridge University from the late nineteenth century. Almost all of the men associated with Bloomsbury attended Cambridge, and several were elected to its exclusive intellectual society, The Apostles. The thinking of the philosopher Bertrand Russell, and that of his peers and pupils, was resolutely anti-idealist – it argued for the persistence of real objects even when they were unobserved. The idealist, metaphysical thought that dominated the European avant-garde, on the other hand – derived from Immanuel Kant and George Berkeley and in the early twentieth century most publicly promulgated by Henri Bergson – rested upon the argument that reality has no independent existence from the subjectivity of its observer.

Since he was not a Cambridge student, and given his potential encounters with practices within a continental vanguard profoundly influenced by Bergson, we might say that Grant, along with Vanessa Bell, was perhaps the exception to Bloomsbury’s strain of thought. However, though Grant and Bell encountered art influenced by Bergson there is no evidence that their art was directly affected by his ideas. There is no record of Grant attending any of Bergson’s lectures while he was in Paris or reading any of his books, even in translation.32 He did meet Madame Bergson and her two daughters over tea at Gertrude Stein’s apartment in March 1914, but this came well after Grant had used Bathing to develop principles of figural flow through rotation and displacement – ‘flow’ often being read as symptomatic of Bergsonian influence. We might anyway doubt Madame Bergson’s infusion of her husband’s thought with any strength to guests at a tea party. Grant’s knowledge of Bergson’s ideas probably came principally from the philosopher Karin Costelloe, whom he had first met in 1910 when she was studying at Cambridge, as Russell’s pupil, and already working on papers about Bergson.33 The two would become close in 1911, and in 1914 Costelloe would marry Grant’s good friend Adrian Stephen, Vanessa Bell’s younger brother. Costelloe’s 1913 presentation to the Aristotelian Society, ‘What Bergson Means by “Interpenetration”’, was attended by many members of the Bloomsbury Group, including Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf. Costelloe used that occasion to offer a robust defence of Bergson against the critiques of George Moore and Bertrand Russell. However, as the philosophy scholar Andreas Vrahimis has shown, her position was ultimately rather closer to the analytical philosophy of Bergson’s critics than to the French thinker’s metaphysics.34

If Grant and Bell were not so directly associated with Russell and his precursors in analytical thought at Cambridge as were the likes of Strachey, Leonard Woolf or Roger Fry, we should nonetheless remember that Fry was their intellectual and artistic mentor and patron. He was the most important single figure in their lives as artists. Fry was an undergraduate at Cambridge from 1885 to 1888, becoming an Apostle in 1887. He thus left the university before Russell’s arrival, but was profoundly affected by the older empiricists including Alfred North Whitehead (shortly to become Russell’s tutor), and younger fellows such as Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson.35 The literary scholar Ann Banfield observes that Fry provided a link between the visual arts and the Cambridge thinkers, who were otherwise, in Clive Bell’s opinion, ‘aesthetically blind’.36 I do not want here to detail the minutiae of the philosophical positions espoused by the three thinkers whom I suggest most directly influenced Grant – for one thing, I doubt that Grant would have followed them as a philosopher might. Rather, he probably derived from them loosely defined concepts that could be explored – rather than necessarily represented – by visual means. Banfield remarks that Grant’s friend Virginia Woolf did not need a formal training in philosophy in order to acquire an ex auditu understanding of arguments that might be of value in her art. Philosophical conversation was an essential part of the culture in which she developed as a writer; the conditions for Grant as a painter were hardly any different.37 Indeed, we know that he encountered these debates beyond Bloomsbury, for they were also a day-to-day element of the Parisian art world. That March 1914 issue of Les Soirées de Paris, for example, contained an illuminating account by the futurist Giovanni Papini of the differing positions of Bergson and the neo-Hegelian Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce.38

I suspect that developments in the thought of Fry and Russell had a crucial influence on Grant and Bell in their turn to abstraction in 1913. There is an important shift within Russell’s philosophy around 1913–14, with the publication of The Problems of Philosophy (1912) and Our Knowledge of the External World (1914). It is at this point that Russell argues how the imperceptible may be made perceptible through processes of compression and abstraction. To describe an object in the world solely in terms of its visual appearance – the epistemic grounding of photography and cinema – is not to understand it adequately as an object of knowledge; knowledge demands a wider, analytical method and sensorium. There is, therefore, a shift from the natural form to the abstract, because the illustrative obscures the relationship with the essential. This expansion of the sensorium by which knowledge is obtained and the object understood is crucial to Russell’s critique of Bergson, also published in 1914. Russell complains that Bergson ‘exalts the sense of sight at the expense of the other senses, and his views on space would seem to be largely determined by this fact’.39 In some respects, we might see the writing on aesthetics of both Fry and Clive Bell, with the latter’s stress on the simplification of objects into ‘significant form’, as anticipating Russell’s philosophical move towards abstraction. Both Fry and Bell undertake compelling, and damning, analyses of impressionism as a terminal point in the imitation of surface appearances.40 The prefix to the titles of Fry and Desmond MacCarthy’s crucial post-impressionist exhibitions of 1910 and 1911 is not simply about style – it addresses how the relationship of subjects and objects in the world is conceptualised after impressionism. Banfield demonstrates how this escape from the realistically represented to the sensed, in Fry’s thought, comes to influence Woolf’s post-war writing.41 Grant and Vanessa Bell, exposed to the development of the ideas of Fry and Clive Bell in greater detail and at length from 1910 onwards reflect them in their pre-war painting by moving towards abstractions from nature that may be apprehended within a wider field of experience than the purely visual. In his work in 1914, both in the designs of carpets for the Omega and for the Scroll, Grant effectively abstracts from nature the rhythmical forms that he had depicted in Dancers and Bathing.

Given this abstraction, we nonetheless have still to account for the rhythmic procession of abstract forms that flow along the canvas of the Scroll and which would be both activated before its audience and accompanied by music. We have seen how, after his encounter with Matisse in 1911, Grant quickly developed a notion of pictorial flow in Bathing. However, by 1913–14, that concept of flow is not necessarily limited to static images within a frame but found in a number of different flows within the artwork and the environment through the ‘translation’ of artworks into domestic objects and spaces. Furthermore, by 1913, Grant had from Fry a fresh concept of rhythm: the idea of ‘musicality’ within the relationship of abstract forms. The experiments of the Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky with abstraction were known to Grant and Bell before 1913, but Fry had expressed his doubts about the project, and Kandinsky was not included in either post-impressionist exhibition. However, in August 1913 Fry would make a telling remark about Kandinsky, one reflecting an important shift in his own position concerning abstraction and of particular relevance for Grant’s work in 1914. Discussing two of Kandinsky’s abstract compositions, Fry wrote ‘They are pure visual music, but I cannot any longer doubt the possibility of emotional expression by such abstract visual signs’.42 Fry had been working towards this position for some time: Richard Cork has noted that his analysis of Wyndham Lewis’s Kermesse 1912 contains similar ideas.43 But Fry had originally developed the idea in the catalogue of the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in late 1911, where he used the term ‘visual music’ to denote an autonomous abstract art predicated upon the modulation of form.

We should, therefore, be wary when technological precedents are used to licence an immediate association of form and music in the Scroll in 1914, since Grant already had well-established critical and practical models from painting in the previous three or four years, as well as recent exposure to futurism’s attempted synthesis of music and painting. An example of these rather random claims is Tate’s equation of the work in 1975 with the ‘Colour Organ’, designed and built by A. Wallace Rimington, Professor of Art at Queen’s College, London, and the proposed use of a similar device to accompany Alexander Skriabin’s symphonic composition Prometheus in spring 1914.44 These equations often rest upon historical solecisms: Grant could not have been at the Queen’s Hall concert of 1 February where a programme note stated that Skriabin would have a ‘tastiera per luce’ to go with the orchestral performance on 14 March – he was in Paris. By the time of that March concert – undertaken, in any case, without the use of the ‘keyboard of light’ – Grant had already, in Paris, sketched out the dynamic colour transitions that would characterise the Scroll. Furthermore, Rimington’s ‘Organ’ was scarcely novel: different iterations had been widely publicised and used in performance without music since the 1890s and as recently as June 1912, in St George’s Hall, Bradford.45 Secondly, there are technical inconsistencies: both Rimington’s device and that proposed for Skriabin depended upon screen projection in theatres and concert halls. This does not sit comfortably with the Scroll, which derives its scale and modus operandi from Chinese handscrolls and offers its audience a viewing window that would be, at most, 600 x 280 mm and therefore almost invisible within such venues. In British culture, Grant was more likely to have been influenced by the painter A.B. Klein, a follower of Kandinsky who would write about the art of colour music in the 1920s. His exhibition Compositions in Colour-Music, and Studies in Line and Shape was staged in May 1912 at the Ryder Decorative Co., Chester Square, London, and was covered by national newspapers. However, Grant simply did not need such models: the work was already developing under the influence of Fry’s concept of abstract music, Russell’s model of abstraction and experience and the artist’s exposure to synaesthetic and intermedial practices elsewhere in European modernism.

Finally, I want to show how Costelloe’s critique of Russell’s critique of Bergson may have directly influenced Grant. Regardless of whether he heard her address to the Aristotelian Society, Grant certainly knew Costelloe well enough to discuss her ideas outside of that forum. Costelloe’s subject in that paper, interpenetration and sense data, is of particular importance in providing a theoretical basis for Grant’s experiments with form and movement in 1914. Vrahimis defines Bergson’s account of human memory with remarkable concision: ‘In Bergson’s view of memory, the past and present interpenetrate within a continuum, which spatial thinking of discrete units by necessity fails to capture’.46 To put this into the terms of Grant’s art before 1914, in a work such as Bathing, while we see a temporal flow across the canvas from right to left, it is not a continuum but rather a series of autonomous, static positions, or discrete units, at intervals. Russell’s critique suggests that Bergson confuses knowing, the recollecting of the past within the present, with the object or event of knowledge. Costelloe’s challenge to Russell was that he misunderstood Bergson here, by seeing the act of knowing the past as static when it was effectively a process that could not be reduced to a series of static moments. Costelloe thus introduced to representation a concept of continuous temporality and change that eliminated the interval and the moment-object.47 Costelloe allows a rational basis for this knowledge, through the process of what she terms ‘introspection’, so that knowledge of events, or objects, is a continuous, creative and self-aware process. Costelloe’s thinking here has parallels with that of Fry from 1910 onwards, as outlined by art historian Sam Rose, who contrasts Fry’s notion of form with that found elsewhere in modernism: ‘[his] more nuanced structural view of form has the advantage of going beyond static conceptions of form as shape, dealing as it does with organisations moving through time, just as its close engagement with the actual operations of the work moves beyond the experience of form as transcendent and indefinable’.48

Having suggested that Bathing might show us a series of static, separated instants, how does the Scroll differ in its disposition of forms? Firstly, the forms are, as we showed in our introduction, mostly linked. There are only three sets that are not in fact conterminal: so there is along the length of the canvas a continuous process of change within form, almost entirely without interval. Secondly, those forms moved: there was not only the appearance of movement between sets, but the substrate on which they are glued or painted actually moved, even if only wound by hand. Thirdly, those movements were not consistent: there is neither a formal pattern in the development of the arrangement of sets within the Scroll, nor is the speed of the Scroll in movement itself necessarily constant – even if the film of the Scroll is. Indeed, prior to Tate’s imposition of a single speed, Grant and Tate curator David Brown had discussed varying lengths for the work.49

I suggest that the models of the knowledge of objects in time and space presented by Russell, Fry and Costelloe offered Grant ideas for the practical treatment of temporal-spatial relations within the pictorial field. If Fry’s thought on aesthetics was that with which Grant was most familiar and to which he was most exposed, as well as pertaining directly to the practice of art, Costelloe, from within philosophy, offered him a transparent, and useful, exposition of subjective experience of relations between objects in time and space. Costelloe’s understanding of ‘sense data’ (that experience) in 1913 accords with what Grant and Bell were to work out practically in their kinetic designs for the Omega Workshops, but might equally well be translated into the relationship between objects moving in time and space that is the central concern of the Scroll. And we should perhaps bear in mind – given Banfield’s paradigm of ex audito transmission of ideas within Bloomsbury – that as Grant began work at Asheham, Costelloe was also a guest at the house.50

Within the Omega-designed interior, whether in the relation of clothed, mobile bodies to static walls and furniture, or in the passage of bodies over carpets that are, effectively, paintings transposed to the floor, or, indeed, in the passage of the Scroll past a few spectators, what Bloomsbury artists were exploring, as a concept, was the relation of objects to subjects in space. Banfield shows how this philosophical concern influences Woolf’s writing in both the polemical essay ‘A Room of One’s Own’ (1929) and her novel To the Lighthouse (1927).51 We might see the interpenetration of objects and subjects in Bloomsbury’s experiments with the visual and the haptic as exploring the same thematic, but without textual articulation. That is, philosophical concepts are investigated as real-world projects, without, certainly, ever being thought of as experiments that would satisfy the discipline’s methodological rigour.

Conclusion: Rhythm and kinesis in Bloomsbury’s domestic arrangements and the Scroll

Roger Fry established the Omega Workshops in 1913 as a way both of more widely disseminating the practice of contemporary art by bringing it into the domestic sphere and of supplementing the income of artists. Setting up the Omega was less innovative than it perhaps appeared to British audiences: as an accomplished art historian, Fry would have known that painting entered the domestic space as narrative decoration before it was ever understood as an independent, privileged activity. As a critic and curator of contemporary art who affirmed its continuity with earlier practices and modes of exhibition, Fry would have had few qualms in re-establishing connections which depended upon different relationships between the spectator and the work of art; relationships, indeed, which might turn the spectator into a participant and that also challenged the status of collectors and connoisseurs in the priority given to fine art.52

Grant and Vanessa Bell were two of the artists most actively employed by the Omega, and their involvement coincided with the period in which they pursued abstract painting. Designs attributed to the couple include printed fabrics, firescreens, chair seats, marquetried furniture, tiles and a large number of rugs and carpets. Some of the preliminary sketches are marked with pinholes where the drawing has been transferred to a more formal design from which a professional craftsman can produce the intended object. It is worth bearing this in mind when we consider the dysfunctionality of the Scroll as it survives. Grant and Bell were clearly familiar with making loose, prototypical sketches for projects that might eventually be realised on a different scale. I am deliberately cautious in separating Grant and Bell in this context: ascription of their authorship is often provisional, since they collaborated so extensively; similarly, much of their abstract painting appears to be a correspondence, or exchange of ideas – Bell’s letter to Fry, which first described the Scroll made it clear that the two had discussed at least some of its conceptual premises. In the case of their carpets, the making of prototypes for manufacture clearly involved a considerable scaling-up from the original drawing; we can see from the dimensions given on Grant’s drawing of a winding device that to fit it the canvas and collaged Scroll would require considerable scaling down. However, that reduction in scale would then render the work operative within the technologies available to Grant in 1914.

As significant as the artist’s experience of making prototypes for domestic objects is the transformed relationship between the visual form and body implicit in these designs, once realised. The new opportunities for artistic practice promised by the Omega Workshops, through the translation of easel painting into domestic objects and decoration, allowed Grant and Bell to further explore the concepts presented to them by Russell, Fry and Costelloe in understanding human experience in time and space. The Omega also allowed them to respond to the artwork of others who were similarly concerned with finding new forms of visual language in which to engage with modernity. Forms which might have been merely visible in easel painting could now be sat upon, trodden underfoot or worn. Grant and Bell’s work with rugs and carpets almost perfectly emblematises the art historian Joseph Masheck’s thesis of how modernism derived from the flat, patterned surface of the domestic interior an idea of abstract decoration that could be turned through ninety degrees and used against the ideal of the painting as window-on-the-world that had served western art since the Renaissance.53 Except that in Grant and Bell’s project, that rotation may be made in either direction.

Fig.12

Duncan Grant

Sketch on the cover of the March 1914 issue of Les Soirées de Paris

Simon Watney Papers, Tate Archive TGA 20036/4

Fig.13

Duncan Grant

Rug design, 1913–15

Gouache, pencil and collage on tracing paper

535 x 145 mm

Courtauld Gallery, London

© The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London/1978 Estate of Duncan Grant, courtesy of Henrietta Garnett

A stair-carpet or rug in the designs of Grant and Bell, in 1913–14, is a painting that may be walked on. Rather than there being an act of static, disinterested contemplation of form, form and body are bound together in a continuously changing kinetic process of which the moving subject is wholly aware, through consciousness of its embodiment. In that sense, in walking on an Omega rug one has something in common with Lucy Wilhelm’s readerly traversal of The Trans-Siberian Prose; and neither act is in any way cinematic, because vision is not prioritised over haptic sensation. There are profound formal similarities between these sketches for carpets and for Grant’s Scroll, to such an extent that Simon Watney could mistake the artist’s sketch on the cover of Les Soirées de Paris as a preliminary design for the latter when it is so closely allied to the former (fig.12). The design is repeated in a rug design of 1914, attributed to Grant (fig.13). Conceptually, there are fewer differences between a carpet and the Scroll than we might imagine: if one is a static painting that the viewer walks over – or indeed, dances upon – the other is a painting that moves past the viewer. Both require a transposition to the domestic scale to become operative; at that scale both forms of kinesis may be accompanied by music. Furthermore, the movement of the Scroll, behind – in Brown and Grant’s version of its viewing in the 1970s – a viewing window with dimensions no bigger than those of an early television screen solicits intimate engagement rather than cinematic viewing. If we scale the window to fit a case that would cover the sketched winding mechanism – as we did in our projection of the Scroll as operative device – then there is little change in this relationship, except that there may be only two or three viewers, close up.54 Our case, of course, is hypothetical, if material, as is the window on the work. But then so is the case in which Brown and Grant’s 1970 viewing window is cut, to the extent that it has never even been sketched out, far less made. The viewing window in Brown’s description symbolises a material and intellectual void in Tate’s conception of what the Scroll might actually have become.