CCX 90–92a; CCXVI 1–270

Sketchbook with boards bound in brown leather tooled with a design along each outer edge, also remains of brass clasp

Paste-downs, recto of front flyleaf, verso of back flyleaf comprised of blue, red and yellow marbled paper

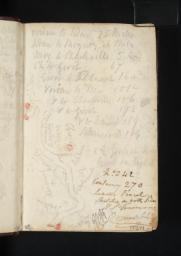

Signed and inscribed in black ink by Henry Scott Trimmer ‘No 242 | Contains 270 | Leaves Pencil | Sketches on both sides | H.S. Trimmer’ and Charles Turner

Inscribed in blue ink ‘242’ centre towards right of inside back cover paste-down

Signed in pencil by John Prescott Knight ‘J.P.K.’ and Charles Locke Eastlake ‘C.L.E.’ on folio 1 recto: (Tate D19552; Turner Bequest CCXVI 1)

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram towards bottom right of back cover

Stamped in black ‘CCXVI’ at top right of front cover and top left of inside front cover paste-down

Watermark ‘smith & allnut | 1822’

Approximate size of page 118 x 78 mm

Paste-downs, recto of front flyleaf, verso of back flyleaf comprised of blue, red and yellow marbled paper

Signed and inscribed in black ink by Henry Scott Trimmer ‘No 242 | Contains 270 | Leaves Pencil | Sketches on both sides | H.S. Trimmer’ and Charles Turner

Inscribed in blue ink ‘242’ centre towards right of inside back cover paste-down

Signed in pencil by John Prescott Knight ‘J.P.K.’ and Charles Locke Eastlake ‘C.L.E.’ on folio 1 recto: (Tate D19552; Turner Bequest CCXVI 1)

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram towards bottom right of back cover

Stamped in black ‘CCXVI’ at top right of front cover and top left of inside front cover paste-down

Watermark ‘smith & allnut | 1822’

Approximate size of page 118 x 78 mm

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

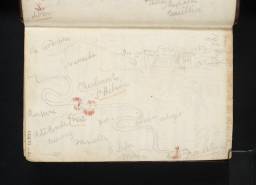

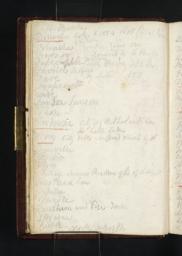

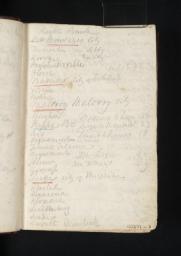

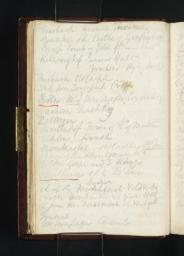

Of the four sketchbooks used by Turner during the 1824 tour, the Rivers Meuse and Moselle is certainly the richest in visual information and the most varied in subject matter. It is a storehouse of memory. It is replete with detailed studies, views sometimes crammed twelve to a page, swiftly dashed-off and cursory sketches, colour notes, inscriptions, financial calculations, maps, compass bearings and notes on distances, as well as handwritten extracts from books. The sketchbook itself, as Cecilia Powell notes, is ‘scarcely bigger than a pocket diary’, but bound within its calf-skin boards are two hundred and seventy pages, each leaf diligently filled on both recto and verso.

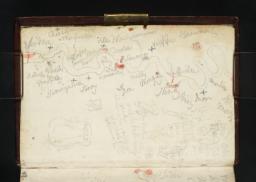

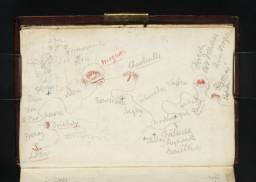

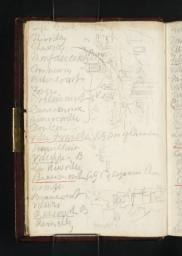

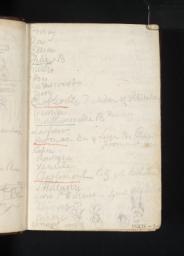

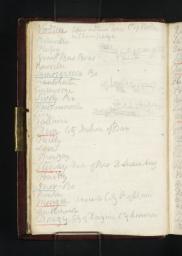

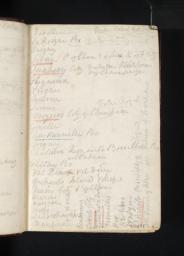

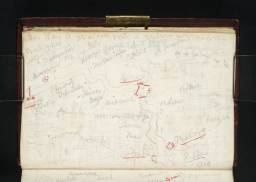

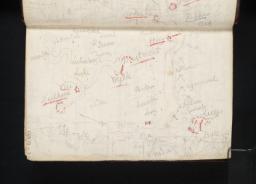

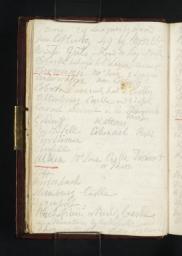

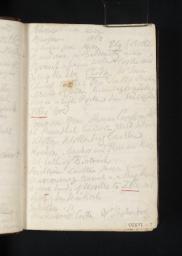

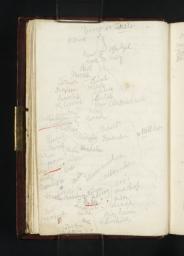

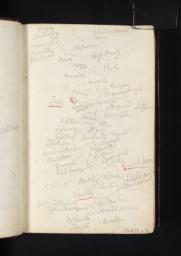

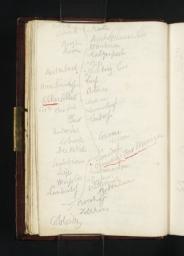

The book opens with nine double-sided pages of sketch maps and notes, copied by Turner in preparation for his journey from up-to-date maps and the contemporary guidebook by Alois Schreiber entitled The Traveller’s Guide down the Rhine (see Tate D40727, D19552–D19569; Turner Bequest CCXVI 1–9a). The maps and extracts transcribed by Turner from the ‘Third Excursion’ of Shreiber’s Guide also include red and blue underlines and crosses under place names as well as circles and jagged circles drawn in red ink. Cecilia Powell has found that these markings correspond exactly ‘to the usage in Schreiber’s map of bold type for important places, a circle for “Walled or open towns” and a similar jagged circle for “Fortified towns”’.1

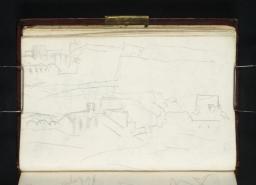

The drawings that follow chart the entirety of the five-week tour, Turner having employed this sketchbook more or less consistently through his travels. It is thus the most comprehensive of the group, encompassing every one of the artist’s destinations in northern France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany, and each of the three major rivers he set out to study: the Meuse, Moselle (known as the Mosel in Germany) and Rhine (see the general Introduction to this tour for the full itinerary described).

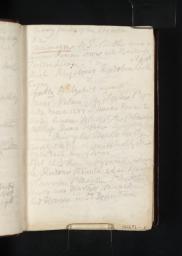

In addition to the natural landscape, the artist remained equally attentive to the human geography he encountered. He records lively quayside scenes at Koblenz (occasionally given as ‘Coblenz’), Dieppe and Liège (Tate D19822, D20008, D20061, D20063–D20064; Turner Bequest CCXVI 136, 233, 260a, 261a–262) and fishwives searching for bait and shrimp on the beaches of northern France (Tate D19995, D19997; Turner Bequest CCXV 226a, 227). A street view at Dieppe is brought to life through inscribed details recording buildings like the tobacco storehouse, the Customs Office, and a café selling wine and absinthe (Tate D19988, D19990; Turner Bequest CCXVI 223, 224). Turner also notes the moment when horses which towed his barge from a path were ‘obliged to swim’ down the middle of the Meuse (Tate D19607, D19609; Turner Bequest CCXVI 28a, 29a), as well as an accident to the artist’s own diligence on the road between Ghent and Bruges (Tate D19863; Turner Bequest CCXVI 154a).

Importantly, Turner inscribed a full and dated itinerary of the first Meuse-Moselle tour at the rear of the sketchbook (Tate D20080; Turner Bequest CCXVI 270). As art historians have struggled to date vast numbers of Turner’s works over the decades, such a schedule of travel, written in the artist’s own hand, is invaluable. It has enabled the precise dating of drawings produced on this tour to be determined even to the exact days on which they were created in the late summer of 1824.

In all, this sketchbook shows Turner to be an inveterate and energetic traveller. Its drawings communicate his visual acuity, his relish of the journey, his desire to record prospect after prospect minute by minute (see, for example, these views of the Moselle: Tate D19744–D19756; Turner Bequest CCXVI 98–104). For the art historian Michael Bockemühl, the Rivers Meuse and Moselle sketchbook in particular is a document that reveals Turner’s total cognitive, visual and graphic immersion in the landscape. A leaf in this book can ‘reveal a dozen views at once’, each scene:

one next to the other, occasionally not even separated from its neighbours, as if they had been rapidly sketched on the page from the passing boat. Each view shows only a fragment; what is absent in one view is shown in the next. It is only when one sees the views in sequence that one experiences the infinite entirety of the world.2

The sketches, Bockemühl writes, are equally a means by which Turner gained ‘access’ to the past. By consulting them he was able to return to lived experience, to re-enter the landscapes of the past in the setting of his London studio months or even years after the event. This process of re-immersion is also facilitated by Turner’s own annotations written in situ before the scene, which log such direct observations as the quality of light, or the exact colouring of the sky and so on.

Technical notes

How to cite

Alice Rylance-Watson, ‘Rivers Meuse and Moselle Sketchbook 1824’, sketchbook, December 2014, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, April 2015, https://www