From the entry

Turner completed his first major tour of Italy in 1819–20, departing in the summer of 1819 and returning to London the following February. This six-month expedition proved to be a prolific period of creative activity; Turner filled twenty-three sketchbooks and numerous separate sheets with pencil and watercolour studies (see the ‘First Italian Tour 1819–20’ section by Nicola Moorby in the present catalogue). A decade later, in the summer of 1828, Turner was fifty-three and comfortably established in his artistic career. Two years earlier, he had embarked on a major commission to illustrate Samuel Rogers’s long poem Italy, producing twenty-five vignettes of Italian views (see Meredith Gamer’s ‘Watercolours Related to Samuel Rogers’s Italy c.1826–7’ in her ‘Vignette Watercolours c.1826–43’ section of the present catalogue). Italy was evidently on his mind when he planned his next major expedition to ...

Lyons to Marseilles sketchbook 1828

D20990–D21015, D21018–D21132, D41001–D41003

Turner Bequest CCXXX 1–13a, 15–74a

D20990–D21015, D21018–D21132, D41001–D41003

Turner Bequest CCXXX 1–13a, 15–74a

Genoa and Florence sketchbook 1828

D21412–D21536, D21538–D21587, D40997–D40998

Turner Bequest CCXXXIII 1–94a

D21412–D21536, D21538–D21587, D40997–D40998

Turner Bequest CCXXXIII 1–94a

Viterbo and Ronciglione sketchbook 1828–9

D21765–D21821, D21823–D21851, D41121–D41122

Turner Bequest CCXXXVI 1–48a

D21765–D21821, D21823–D21851, D41121–D41122

Turner Bequest CCXXXVI 1–48a

Rome to Rimini sketchbook 1828–9

D14833–D14853, D14855–D14878, D14880–D14881, D14883–D14885, D14887–D14903, D14905–D14932, D40671–D40672

Turner Bequest CLXXVIII 1–55a

D14833–D14853, D14855–D14878, D14880–D14881, D14883–D14885, D14887–D14903, D14905–D14932, D40671–D40672

Turner Bequest CLXXVIII 1–55a

The Route to Rome: French and Italian Landscapes, Bridges, Buildings and Ruins

D33968, D33986–D33991, D33994, D33998, D34003–D34008, D34021, D34023–D34024, D34029–D34036, D34039, D34041, D34047–D34048, D34054, D34510–D34512, D36172

Turner Bequest CCCXLI 253, 270–274, 277, 281, 286–290, 302, 304, 305, 310–317, 320, 322, 328, 328v, 334, CCCXLIV 146–148, CCCLXIV 314

D33968, D33986–D33991, D33994, D33998, D34003–D34008, D34021, D34023–D34024, D34029–D34036, D34039, D34041, D34047–D34048, D34054, D34510–D34512, D36172

Turner Bequest CCCXLI 253, 270–274, 277, 281, 286–290, 302, 304, 305, 310–317, 320, 322, 328, 328v, 334, CCCXLIV 146–148, CCCLXIV 314

References

Turner completed his first major tour of Italy in 1819–20, departing in the summer of 1819 and returning to London the following February. This six-month expedition proved to be a prolific period of creative activity; Turner filled twenty-three sketchbooks and numerous separate sheets with pencil and watercolour studies (see the ‘First Italian Tour 1819–20’ section by Nicola Moorby in the present catalogue).1

A decade later, in the summer of 1828, Turner was fifty-three and comfortably established in his artistic career. Two years earlier, he had embarked on a major commission to illustrate Samuel Rogers’s long poem Italy, producing twenty-five vignettes of Italian views (see Meredith Gamer’s ‘Watercolours Related to Samuel Rogers’s Italy c.1826–7’ in her ‘Vignette Watercolours c.1826–43’ section of the present catalogue). Italy was evidently on his mind when he planned his next major expedition to the continent, which began in the August of 1828 and spanned a period of around six months.2 Turner’s precise date of departure is unknown, although he was last seen in London at a meeting at the Royal Academy on 24 July.3

The initial leg of Turner’s journey through northern France is not well documented, although he is known to have arrived in Paris by late August. Turner scholars have debated his exact date of arrival in the French capital; an inscription in the artist’s Roman and French notebook reads ‘11 Augt – Hotel de | Bristol Place Vendome’ (Tate, D21939; Turner Bequest CCXXXVII 49a), which Cecilia Powell read as a reference to the artist’s arrival date in the city.4 Ian Warrell has suggested a later date, however, citing Turner’s letter to his artist friend Charles Eastlake of 23 August: ‘the tone of his letter [...] implies that he had only recently begun his journey, so the details in the sketchbook may be those of a planned rendezvous that had had to be postponed.’5 Turner was back in London by early February 1829, in time to attend a meeting at the Royal Academy on 10 February.6

During his brief stay in Paris, Turner refined his itinerary for the coming months, weighing up two alternative routes. One option was to retrace his steps from 1819, crossing the Alps and continuing via Turin and Milan towards Rome (see Moorby’s introduction to that tour). However, ever eager to ‘see new places and embrace new experiences’, he looked instead for uncharted territory, planning a new route that took in the unfamiliar landscapes of southern France and Liguria.7 As Powell observed, Turner was ‘obviously very interested in the south of France for its own sake and it is worth noting that many travellers regarded the Roman remains there as superior even to those in Rome itself’.8 Tempering these new sketching opportunities, Turner’s detour via southern France also presented obstacles, especially the soaring temperatures and prolonged travel times. As he admitted to his artist friend George Jones in a letter from Rome on 13 October 1828, ‘the length of the time is my own fault. I must see the South of France, which almost knocked me up, the heat was so intense, particularly at Nismes and Avignon; and until I got a plunge into the sea at Marseilles, I felt so weak that nothing but the change of scene kept me onwards to my distant point.’9

Eight sketchbooks are associated with Turner’s 1828–9 tour, seven of which follow a broadly chronological sequence, charting the artist’s route to Rome and back. The eighth book, known as the Roman and French notebook (Tate; Turner Bequest CCXXXVII), contains assorted inscriptions and studies of British, French and Italian subjects, captured both before and during the tour (for example, views of Shoreham, Brighton and Petworth predating Turner’s departure). Historically, two additional sketchbooks were thought to relate to this tour, Orleans to Marseilles and Coast of Genoa (Tate; Turner Bequest CCXXIX, CCXXXII), which overlap with the geographical remit of Lyons to Marseilles and Marseilles to Genoa respectively. However, following further research by Turner scholars including Ian Warrell and Roland Courtot, the two books have since been reallocated to a later journey through southern France and Italy, undertaken in 1838 (see Hayley Flynn’s section in the present catalogue).10

Five of the eight sketchbooks document Turner’s outward journey to Rome. Geographically, they dovetail with one another to form a clear sequence. The initial stretch of the journey from London to Lyon is not covered by the sketchbooks, although Turner presumably travelled from Paris via Orléans, along the Loire and Allier valleys to Clermont-Ferrand, then east to Lyon.11

Lyons to Marseilles (Tate; Turner Bequest CCXXX), the first book in the sequence, charts the artist’s boat journey along the River Rhône from Lyon to Avignon, taking in riverside towns and villages such as Vienne, Viviers, Rochemaure, Pont-Saint-Esprit and Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Disembarking from the boat at Avignon, likely in early September 1828, Turner then travelled by road to Avignon, Nîmes, Marseille and Toulon. Most of the three-dozen separate sheets associated with the 1828–9 tour also relate to this early stretch of the journey in southern France (including views of Avignon, Nîmes, and the Pont du Gard aqueduct situated between the two cities).

The route continues in Marseilles to Genoa (Tate; Turner Bequest CCXXXI), which is dominated by coastal views of the Mediterranean, recorded either from out to sea or from winding coastal roads. Cannes, Antibes and Nice are depicted, together with subjects located between Ventimiglia and Savona, Turner having by this stage crossed over into Italian territory.

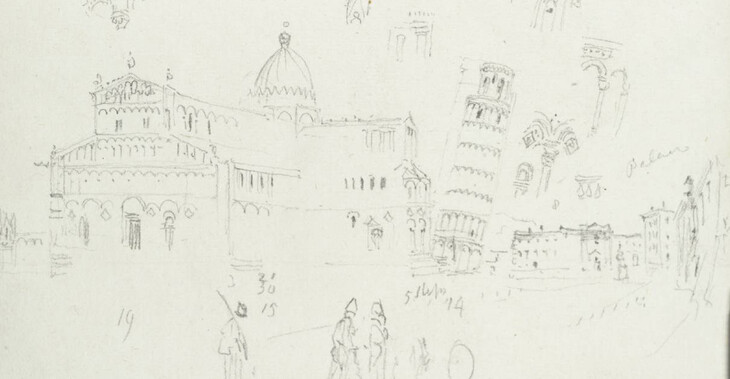

Genoa and Florence (Tate; Turner Bequest CCXXXIII), the third and lengthiest book of the tour, encompasses a significant stretch of the Ligurian coastline east of Genoa, and proceeds via inland roads to Florence. Turner’s busy itinerary took in Genoa, Nervi, Sori, Recco, Camogli, the Portofino promontory, Santa Margherita Ligure, Rapallo, La Spezia, Carrara, Massa, Pisa, Livorno and finally Florence, a city already familiar to him from his 1819–20 tour.

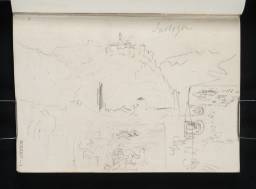

Next in the sequence is Florence to Orvieto (Tate; Turner Bequest CCXXXIV), which aligns closely with a section of the traditional Via Francigena pilgrimage route from Canterbury to Rome. Compared with the proliferation of river and coastal views in previous sketchbooks, Florence to Orvieto is dominated by Tuscan landscapes dotted with hilltop villages and medieval fortifications. Turner’s itinerary included Poggibonsi, Monteriggioni and Siena, progressing via Radicofani, Acquapendente, Lake Bolsena and lastly Orvieto, to which he devoted numerous studies.

The final sketchbook associated with the outward leg of the tour is Viterbo and Ronciglione (Tate; Turner Bequest CCXXXVI), centred within the Viterbo province of Lazio. Beginning south-west of Orvieto in Montefiascone, the route continues via Viterbo, Lago di Vico, Caprarola, Ronciglione and Nepi. Finally, Turner arrived in Rome, where he was to remain for the next three months.

Turner’s arrival in Rome in early October 1828 prompted an immediate shift in his priorities. Accordingly, his daily use of the sketchbooks saw a dramatic decline. As summarised by Powell, ‘the sight of new areas of France and Italy and the sense of excitement at the beginning of a tour provided a strong incentive to sketch which virtually disappeared once he had reached his destination.’12 James Hamilton, too, remarked on how Turner’s agenda changed between the two visits to Rome: ‘Then, he moved about energetically to sketch in all parts of the city. But having done that in 1819 he had the information in his sketchbooks and did not need to do it all again.’13 Instead, Turner’s attentions turned swiftly to painting, an activity that was to preoccupy him until his departure from Rome in early January. This change in artistic medium was not a spontaneous decision but rather a result of careful planning and preparation.

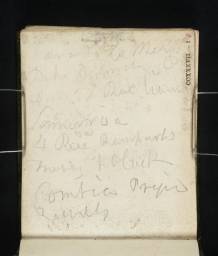

Turner’s intention to devote his time in Rome to painting is revealed by multiple sources. Inscribed in the Roman and French notebook (Tate D21871; Turner Bequest CCXXXVII 11), together with dimensions for seven paintings accompanied by pictographs, are the names of two patrons, Sir (James) Willoughby Gordon, and one of the artist’s major supporters, the third Earl of Egremont, of Petworth House in Sussex (see Elizabeth Jacklin’s section on Petworth c.1827–35 in the present catalogue). Turner seemingly embarked on his tour with specific commissions already in mind, which brought clarity to his focus.

Another key piece of evidence is Turner’s correspondence to Eastlake from Paris, postmarked 23 August 1828.14 In the letter, Turner apologised for ‘not being with you by the time I expected to be in Rome’, and asked his friend to prepare canvases of specific dimensions for his arrival.15 The sketching materials that accompanied Turner on his tour are similarly revealing. In 1819, as Powell noted, ‘he set out with a good supply of sketchbooks of various sizes, including some quite large ones’, and proceeded to fill almost two-dozen books in six months, alternating between pencil, watercolour and gouache. Far fewer sketchbooks were acquired in advance of his second tour, and those he did use were amassed on a more ad hoc basis. Turner possibly purchased individual books en route to suit his requirements.16 Moreover, these sketchbooks tend to be smaller in size.

Turner likely arrived in Rome shortly before 13 October, the date of his letter to George Jones, when he recalled the ‘Two months nearly in getting to this Terra Pictura’.17 He had made arrangements to lodge at No.12 Piazza Mignanelli near the Spanish Steps, where his friend Eastlake had resided since 1819.18 As Hamilton noted, this was an address ‘with a rich history of use by English and Scottish artists and writers. Not only did the Callcotts, Charles Eastlake and Turner stay there, but it was also the studio of Thomas Banks in the 1770s and of the Scottish sculptor James Durno’.19 This hive of activity was characteristic of the wider neighbourhood, a popular haunt for artists and sculptors alike. Turner also had access to a painting studio off the Corso, the road connecting the Piazza del Popolo to the Forum.20

By 9 December, Eastlake reported that Turner ‘had worked literally night and day’, beginning several pictures and finishing three.21 These were the large Vision of Medea (Tate N00513; 1737 × 2489 mm),22 and two, Regulus (Tate N00519)23 and View of Orvieto, Painted in Rome (Tate N00511),24 in Turner’s more customary 3 x 4 feet format (around 915 x 1220 mm); he soon exhibited these to a public audience.25 Inscriptions inside the back cover of the Rome to Rimini sketchbook (D40672) likely relate to Turner’s advertisement of 11 December 1828 for this exhibition. Held at Palazzo Trulli, 49 Via del Quirinale, it reportedly opened on 18 December.26 Despite the modest size of the collection and the transient nature of the display, the exhibition apparently attracted a thousand visitors and caused a sensation. Aside from the exhibited paintings, Turner also developed but left unfinished several other ambitious works on canvas, among them Southern Landscape (Tate N05510),27 and a series of smaller oil sketches.28

The status of another large painting, Palestrina – Composition, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1830 (Tate N06283), is less certain; though apparently begun there, it does not seem to have been shown in Rome, but it was likely intended for Lord Egremont, although he did not acquire it;29 see under D21871 in the Roman and French notebook, as mentioned above, where a corresponding set of dimensions is associated with Egremont’s name.

Turner’s brief notes inside the front cover of the Rome, Turin and Milan sketchbook (Tate D41050; Turner Bequest CCXXXV) imply that he departed from Rome on 3 January 1829. As it transpired, this was to be his last visit to the city. Just two sketchbooks concern the return leg of the journey, the first of which is Rome to Rimini (Tate; Turner Bequest CLXXVIII). Its remit covers the mountainous terrain of the Umbrian Apennines, the hilly landscapes of Marche, and coastal views of the Adriatic Sea near Ancona and Rimini. It then stretches as far north as Bologna and Piacenza, despite the title. Much of the route aligns with the Via Flaminia, an ancient road connecting Rome to Rimini via the Apennines.

Finally, the Rome, Turin and Milan book concludes the tour with views of the Lombardy and Piedmont regions of northern Italy. Lodi, Milan, Boffalora Sopra Ticino, Turin, Susa and the Mont Cenis pass are among the locations depicted, and Alpine views naturally dominate. Whereas his outward journey was characterised by the oppressive heat of Provence, Turner now struggled with heavy snow and plummeting temperatures, which occasionally postponed his departure times and delayed his journeys. These challenging environmental conditions likely account for the low number of sketchbooks associated with his return journey. Turner may also have travelled by night with the post to save time, limiting his sketching opportunities. After Mont Cenis, there are very few sketches charting the artist’s route to London via France.

Turner had hoped to exhibit some of his Rome paintings at the 1829 Royal Academy exhibition on his return, and requested that his canvases be shipped to London. However, the protracted delivery times caused him to abort these plans; Regulus and View of Orvieto arrived three months after the Academy opened.30 The extent to which Turner later reviewed and reinterpreted the sketchbooks and sheets from his 1828–9 tour remains open to conjecture. A rich repository of architectural and topographical detail, they no doubt provided inspiration for future works. One example is Rome, from Mount Aventine (private collection), an oil painting exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1836.31 It appears to be based on a series of panoramas Turner sketched in pencil during his stay in Rome (see the Rome to Rimini sketchbook: Tate D14839–D14843; Turner Bequest CLXXVIII 4a–7).

Writing extensively on Turner’s use of the sketchbooks in Italy, Nicola Moorby described how these items were ‘ready to hand at every stage of the journey’, embodying ‘the repository of his experiences. His use of them extended before, during and after his travels, and they became an invaluable tool not only in preparing for and recording his Italian experiences, but also for digesting and interpreting them.’32 While Turner’s sketchbooks are occasionally instructive for their preparatory role in relation to the oil paintings, they hold intrinsic value in their own right. Illustrating the artist’s versatility and adaptability, they reveal how Turner tailored his sketching methods to his mode of transport, using the natural progress of a boat or carriage to create multiple profiles of a single landmark, such as a bridge or castle ruin (see, for example, Tate D21037, D21052; Turner Bequest CCXXX 24a, 32). The drawings convey his profound appreciation of his changing topographical surroundings, as he worked tirelessly to record rivers, valleys, coastline, hills, mountains and cityscapes. They reflect his fluency in a range of compositional styles as he alternated between vertical and horizontal positions of the sketchbook, finding the optimum orientation for his subject. They also show his capacity for working with the sketchbook’s restrictive dimensions, as he scaled down a panoramic vista to a double-page spread (Tate D21824–D21825; Turner Bequest CCXXXVI 32a–33).

The 1828–9 sketchbooks evidence the pressured working conditions of the travelling artist, and the time-saving devices Turner relied on for economy. In several examples, he annotated his drawings with numbers to avoid repetition (Tate D21616; Turner Bequest CCXXXIV 15), or used colour annotations to capture fleeting impressions of a sunset (Tate D21818; Turner Bequest CCXXXVI 29). Other sketches show how he balanced representative sections of detail with swathes of blank space (Tate D34007; Turner Bequest CCCXLI 289), or used shorthand to denote more complex forms. The sketchbooks also confirm his strong predilections for certain architectural typologies and natural phenomena: bridges, aqueducts, classical ruins, castles, belltowers, lighthouses, and distinctive mountain formations. Finally, they testify to his well-honed ability to seek out advantageous viewpoints, whether from a hilltop or rocky promontory overlooking Florence (Tate D21487; Turner Bequest CCXXXIII 38a) or Avignon (Tate D21072; Turner Bequest CCXXX 42), or from the depths of a river valley or volcanic ravine, looking up towards cliff faces, towers and ruins (Tate D21038, D21782; Turner Bequest CCXXX 25 and CCXXXVI 9a).

While a significant body of scholarship on Turner assisted with the process of cataloguing the present tour, the author is particularly indebted to the research of two scholars. Meticulously set out and illustrated in a series of online blogs, Roland Courtot’s geographical expertise was invaluable, especially when identifying the French subjects.33 Cecilia Powell’s research, initially undertaken for her doctorate on Turner, was similarly vital in fleshing out the Italian sketchbooks.34 Many of the identifications in the present tour would not have been possible without their careful research. The author would also like to thank Nicola Moorby, formerly a Tate cataloguer, whose extensive work on the ‘First Italian Tour 1819–20’ was a welcome frame of reference when cataloguing the second tour. Moorby also contributed significantly to researching and writing the entries for one of the sketchbooks in the present tour, Marseilles to Genoa.

On the first Italian tour, see Powell 1987; Ian Warrell, David Laven, Jan Morris and others, Turner and Venice, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2003; and Hamilton and others, Turner & Italy 2009.

The most detailed accounts of the second Italian tour can be found in Powell 1987, ‘Return to Rome, 1828’, pp.137–65; Hamilton and others 2009, ‘A Roman Triumph’, pp.69–77; and several blogs by Roland Courtot, Carnets de voyage de Turner, accessed 13 January 2025, https://carnetswt.hypotheses.org/1 .

For an account of this reallocation of the sketchbooks between the two tours, see Roland Courtot, ‘5. Dates et itinéraires des carnets de Turner à travers le sud-est de la France’, Carnets de voyage de Turner, accessed 29 January 2024, https://carnetswt.hypotheses.org/517 . See also Courtot 2016, pp.95–6.

Butlin and Joll 1984, pp.171–2 no.293, pl.295 (colour; exhibited again at the Royal Academy, London, in 1831).

Ibid., pp.172–3 no.294, pl.296 (colour; extensively reworked for the 1837 British Institution exhibition in London).

See ‘Nos. 296–328: Unexhibited Works’, ibid., pp.174–82 nos.296–328a, pls.281, 298–300, 302–330, 332); the status and dating of those from no.318 onwards is more speculative.

Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, revised ed., New Haven and London 1984, p.217 no.366, pl.370 (colour).

Moorby, in Hamilton and others 2009, p.132. For further analysis of the artist’s use of sketchbooks, see Moorby’s chapter ‘An Italian Treasury: Turner’s Sketchbooks’, in Hamilton and others 2009, pp.111–7.

Roland Courtot, Carnets de voyage de Turner, accessed 13 January 2025, https://carnetswt.hypotheses.org/1 .

How to cite

Hannah Kaspar, ‘Second Italian Tour 1828–9’, January 2025, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, February 2025, https://www