Turner Bequest CCV 1–41a

Sketchbook bound in boards, covered in grey marbled paper quarter-bound over brown leather spine

44 leaves and paste-downs of white wove paper, page size 98 x 162 mm

Various leaves watermarked ‘1821’ and with partial ‘lls | 1’

Inscribed by Turner on a label on the spine in ink ‘91 London Bridge’ (now lost)

Numbered 244 as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest, inside front cover (D40961)

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram on front cover, top left

Stamped in black ‘CCV’ on front cover, top right

44 leaves and paste-downs of white wove paper, page size 98 x 162 mm

Various leaves watermarked ‘1821’ and with partial ‘lls | 1’

Inscribed by Turner on a label on the spine in ink ‘91 London Bridge’ (now lost)

Numbered 244 as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest, inside front cover (D40961)

Blind-stamped with Turner Bequest monogram on front cover, top left

Stamped in black ‘CCV’ on front cover, top right

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

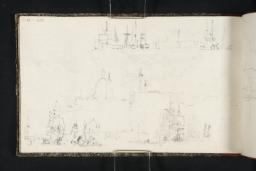

More than half of the drawings in this sketchbook focus on Old London Bridge and its surroundings along the River Thames.1 Building work began on its replacement, just upstream, in March 1824,2 but Turner would meanwhile celebrate the much-renovated medieval structure in a watercolour, signed and dated 1824, known as The Port of London (Victoria and Albert Museum, London),3 which was engraved in 1827 as Old London Bridge and Vicinity (Tate impression: T06070); see the overall Introduction to the present Thames-related section.

The bridge, its environs and the beginnings of work on coffer-dams to facilitate construction are shown on folios 2 verso, 3 recto, 6 verso–15 verso, 16 verso–20 verso, 21 verso, 22 verso, 32 verso–37 verso, 41 recto and 42 verso (D17837, D17838, D17845–D17863, D17865–D17873, D17875, D17877, D17889–D17899, D17905, D17908); these pages are here given as ‘?1824’, signifying that the year is the most likely (others being dated to c.1823–4 on the various criteria discussed below). Sketches inside the front cover and on folios 1 recto and 44 recto and verso (D40961, D17834, D17911, D17912) may also have been made as part of the same campaign. See the individual entries for comments on those which seem to have particularly informed the finished composition.4 What seem to be test strokes of watercolour associated with its production are on D17851, D17852, D17854, D17873 and D17893.

Intervening destruction and development mean the Thames waterfront looks rather different today, although the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, the tower of St Magnus the Martyr’s Church and the column of the nearby Monument, seen in many of the sketches here, survive on the north bank, as does the tower of Southwark Cathedral (then St Saviour’s Church) on the south, albeit overshadowed now by the 309-metre (1,014 feet) Shard skyscraper, just to the east of the present incarnation of London Bridge. Along this reach, Turner also shows the early eighteenth-century St Olave’s Church (demolished in 1926) and the neighbouring shot tower, built in the 1780s and perhaps demolished in the middle of the nineteenth century.5

The Old London Bridge material probably dates from after the fourteen monochrome watercolour studies of landscapes and skies on the rectos of folios 21–32, folio 38 recto and folio 39 recto (D17874, D17876, D17878–D17883, D17885, D17888, D17900, D17901); pencil sketches of the bridge are at first interspersed with them on folios 21 verso and 22 verso (D17877, D17879), before Turner seems to have decided to avoid the rest of the continuous recto watercolour sequence and begin again on folios 32 verso–33 recto (D17889–D17890). Ian Warrell has suggested that the artist may have been spurred to the creation of the tonal, inky drawings by a knowledge of his former patron Richard Payne Knight’s6 album of wash studies by the French artist Claude Lorrain (c.1604–1682), who was in any case an important influence.7 Knight acquired the album not long before his death in 1824, and left its contents to the British Museum, London.8 Both the Liber Studiorum and the so-called ‘Little Liber’ (see the relevant section of the present catalogue, c.1806–24 and c.1823–6) owe a debt to Claude – the former in its general concept, style and certain compositions, and the latter perhaps in its emphasis on chiaroscuro.9 Any direct influence of the Payne Knight album on the present sketchbook will probably remain a matter for speculation.

Key clues to dating are the pencil copies of Benjamin Robert Haydon’s new painting The Raising of Lazarus and Rubens’s Chapeau de Paille (on folios 1 recto and 44 recto respectively; D17834, D17911), both of which exhibited in London in the spring of 1823.10 Sketches on folio 28 verso (D17884) may relate to the Haydon.

At the beginning and end of the book, and perhaps made first of all, are sketches of a wide variety of subjects11 including identified views up the Thames in the vicinity of Richmond; Turner still maintained his rural self-designed home across the river at Twickenham at this time (see the present author’s ‘Sandycombe Lodge c.1808–12’ section), and the area had long been important to him for both inspiration and recreation (see David Blayney Brown’s ‘Thames Sketchbooks c.1804–14’ section). Studies perhaps made in or evoked by this part of the Thames Valley are on folios 5 recto, 16 recto, 39 verso, 40 recto (D17842, D17864, D17902, D17903), some of which seem on the way to becoming idealised Claude-like compositions. The little sketch of women as ‘wood nymphs’ among the trees on folio 42 recto (D17907) is consciously Arcadian, while another woodland scene inside the back cover (D40965) is labelled an ‘English Fete Champetre’, evoking Watteau (1684–1721), another French artist important to Turner.

There are several sky studies near the beginning of the book, as noted in the entry for the inside of the front cover (D40961), including two made at or near Twickenham and nearby Kew, while detailed studies of plants occur on folios 1 verso and 2 recto (D17835–D17836); Ian Warrell has suggested that they might have been observed in the artist’s Twickenham garden.12 Sheep (at Richmond) and cows are drawn on folios 4 verso and 43 verso respectively (D17841, D17910), while children at leisure appear on folios 4 recto and 41 verso (D17840, D17906). The latter also features an amorous couple by the water’s edge, among other incidental sketches. Chance encounters seem to have been the impetus for sketches of gypsies and an apparent road accident on folios 40 verso and 43 recto (D17904, D17909). Lastly, a diagram and small architectural studies on folio 23 verso (D40962) have yet to be clearly interpreted or dated.

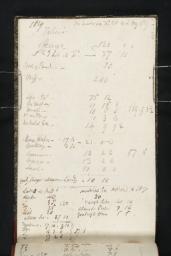

Reflecting Turner’s ongoing professional activities, folios 5 verso and 6 recto (D17843–D17844) comprise detailed transcriptions of selected Royal Academy accounts from 1819 onwards, the last of which date from 13 November 1823; it follows that Turner would have copied them towards the end of the latter year or shortly thereafter, apparently in connection with his election as an Auditor at the General Assembly of 10 December 1823.13

Finberg recorded a label (since lost) ‘on back–“91. London Bridge.”’14 Like those which survive, this was presumably in ink on a white wove paper label pasted onto the spine. David Hill initially suggested that Turner devised his sequence of numbered and annotated labels during a general review of his sketchbooks in about 1821 or 1822,15 later revising this to the second half of 1824 on the dating evidence of some of the relevant books.16 Ian Warrell has subsequently reasoned that the process began in 1823, ending in the summer of 1824,17 coinciding with Turner’s use of the present book. Finberg also recorded John Ruskin’s comments on a wrapper, since lost, as ‘244. London Bridge. Indian ink skies very interesting.’18 It is unclear whether his qualifying note ‘Not in Mr. Ruskin’s own handwriting’ applies to all or part of the inscription.

See Terry Riggs, ‘Knight, Richard Payne (1751–1824)’ in Evelyn Joll, Martin Butlin and Luke Herrmann (eds.), The Oxford Companion to J.M.W. Turner, Oxford 2001, pp.157–8.

See Ian Warrell, Blandine Chavanne and Michael Kitson, Turner et le Lorrain, exhibition catalogue, Musée des beaux-arts, Nancy 2002, and Ian Warrell and others, Turner Inspired: In the Light of Claude, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery, London 2012.

See Warrell in Warrell, Chavanne and Kitson 2002, pp.176, 194 under no.57, Warrell 2012, p.38, and Warrell 2014, p.122; see also Kathleen Nicholson, ‘Turner, Claude and the Essence of Landscape’, in David Solkin (ed.), Turner and the Masters, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2009, pp.60, 227 note 6.

As noted for example in Finberg 1961, p.23, and Butlin, Wilton and Gage 1974, p.97; see also Warrell 2014, p.122.

See David Hill, ‘The Landscape of Imagination and the Sense of Place: Turner’s Sketching Practice’ in Maurice Guillaud, Nicholas Alfrey, Andrew Wilton and others, Turner en France, exhibition catalogue, Centre Culturel du Marais, Paris 1981, pp.143, 147 note 34.

Technical notes

How to cite

Matthew Imms, ‘Old London Bridge Sketchbook c.1823–4’, sketchbook, December 2014, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, April 2015, https://www