‘In these English farms, if anywhere, one might see life steadily and see it whole’: Representations of the Countryside in the Paintings of Robert Bevan and E.M. Forster’s Howards End

Helena Bonett

In the early 1900s many artists and writers revelled in the city. Others, recalling earlier traditions, still looked to the countryside for inspiration. Helena Bonett here compares the country idyll in E.M. Forster’s novel Howards End with the rural paintings of Robert Bevan.

Last Monday a man – named Farman – flew a ¾ mile circuit in 1½ minutes. It is coming quickly, and if I live to be old I shall see the sky as pestilential as the roads. It really is a new civilization. I have been born at the end of the age of peace and can’t expect to feel anything but despair. Science, instead of freeing man ... is enslaving him to machines ... God what a prospect! The little houses that I am used to will be swept away, the fields will stink of petrol, and the air ships will shatter the stars. Man may get a new and perhaps a greater soul for the new conditions. But such a soul as mine will be crushed out.1

Writing in his diary in 1908, E.M. Forster lamented the new mechanised world that was rapidly rendering centuries of tradition outmoded. Similarly, noting the advent of the motor car that was fast replacing horse-drawn vehicles, the critic Frank Rutter described the painter Robert Bevan in 1910 as ‘the historian of the decline of the horse, whose character he gives with a rare half humorous tenderness. Its sorry fate he veils in half-mourning hues of violet.’2 Unlike many artists of the period – from Walter Sickert to the futurists, who revelled in urban life – Forster and Bevan were drawn to the countryside. In this essay I look at Forster’s Howards End (1910) and several of Bevan’s paintings, exploring how both writer and artist conveyed their particular perception of the countryside and rural life.

*

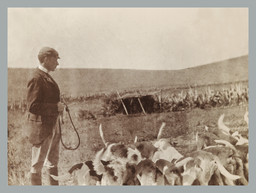

Alice Clara 'Lily' Forster and Herbert Whichelo leaning on the fence at Rooksnest, Stevenage undated

Photographic print

156 x 108 mm

King's College Library, Cambridge. Forster Papers/27/47

By kind permission of the Provost and Fellows, King's College

Fig.1

Alice Clara 'Lily' Forster and Herbert Whichelo leaning on the fence at Rooksnest, Stevenage undated

King's College Library, Cambridge. Forster Papers/27/47

By kind permission of the Provost and Fellows, King's College

‘London’s creeping.’

She pointed over the meadow – over eight or nine meadows, but at the end of them was a red rust.

‘You see that in Surrey and even Hampshire now,’ she continued. ‘I can see it from the Purbeck downs. And London is only part of something else, I’m afraid. Life’s going to be melted down, all over the world.’

Margaret knew her sister spoke truly.5

She pointed over the meadow – over eight or nine meadows, but at the end of them was a red rust.

‘You see that in Surrey and even Hampshire now,’ she continued. ‘I can see it from the Purbeck downs. And London is only part of something else, I’m afraid. Life’s going to be melted down, all over the world.’

Margaret knew her sister spoke truly.5

In the novel Margaret voices Forster’s own private fears about modernisation. Looking to the future she muses, ‘This craze for motion has only set in during the last hundred years’ hoping that ‘It may be followed by a civilization that won’t be a movement, because it will rest on the earth’.6

This anti-modern longing for a rural idyll was felt by many in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It inspired numerous utopian outpourings that envisioned a future golden age in which the city would be replaced by the countryside, most famously in William Morris’s novel News from Nowhere (1890). It also motivated the development of the Garden Cities and Garden Suburbs, such as Letchworth (just north of Rooksnest) and Hampstead, both of which were home to members of the Camden Town Group.7 In this period it was common for artists and writers to work during the summer in rented country cottages. Some even fostered a ‘simple life’ rural persona, such as the painter Augustus John as a gypsy, while others, such as the tramp poet W.H. Davies, were admired for their ‘authentic’ way of life.8 Similarly, members of the Bloomsbury Group, with whom Forster was affiliated, spent long periods working in the countryside.

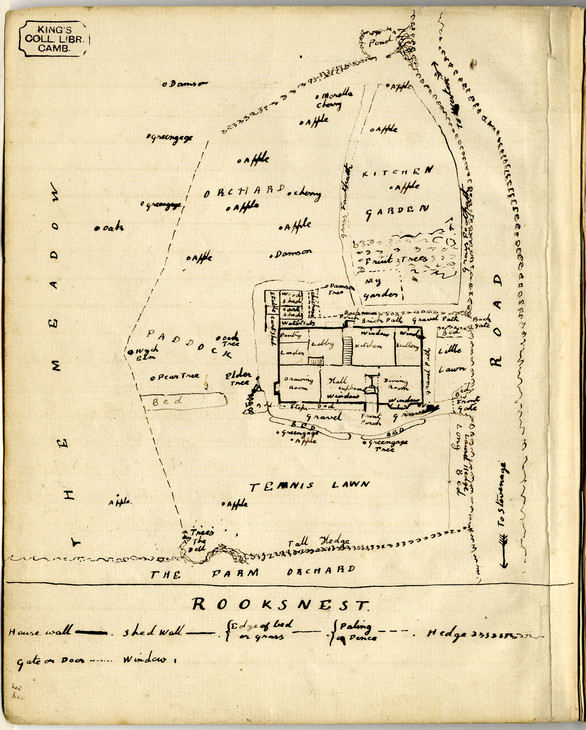

E.M. Forster 1879–1970

Sketch map showing the layout of rooms and design of the garden in the autograph manuscript memoir of Rooksnest, Stevenage 1894–1947 (c.1894, 1901 and 1947)

King's College Library, Cambridge. Forster Papers/11/14

By kind permission of the Provost and Fellows, King’s College

Fig.2

E.M. Forster

Sketch map showing the layout of rooms and design of the garden in the autograph manuscript memoir of Rooksnest, Stevenage 1894–1947 (c.1894, 1901 and 1947)

King's College Library, Cambridge. Forster Papers/11/14

By kind permission of the Provost and Fellows, King’s College

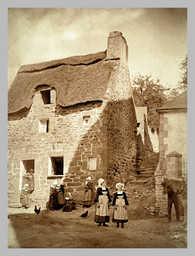

T.B. Latchmore 1832–1908

Photograph of Rooksnest from the front, showing the wych-elm undated Inscribed on the back by E.M. Forster, 'Only record of wych-elm (in Howards End)'

Photographic print

197 x 148 mm

King's College Library, Cambridge. Forster Papers/27/181

By kind permission of the Provost and Fellows, King's College

Fig.3

T.B. Latchmore

Photograph of Rooksnest from the front, showing the wych-elm undated Inscribed on the back by E.M. Forster, 'Only record of wych-elm (in Howards End)'

King's College Library, Cambridge. Forster Papers/27/181

By kind permission of the Provost and Fellows, King's College

Forster was never completely happy in the city and always felt nostalgic for his idyllic childhood at Rooksnest, where from 1883 until 1893 he had lived a leisured existence with his mother, Lily, in ‘an attractive, gabled house with four acres of farm and gardens’ (fig.2).9 Unlike the new-build detached and semi-detached properties in local Stevenage, which to him were ‘ugly new houses’ that ‘much disfigured the road’,10 Rooksnest was proudly described in his earliest known writing at the age of fifteen to be ‘very old. Some said 200 years and some 500.’11 A key symbol in Howards End is the wych-elm in the garden, which evokes the spirituality and sense of ancient inheritance that Ruth Wilcox wishes to pass on to Margaret.12 A wych-elm likewise stood in the garden at Rooksnest (fig.3); the young Forster found pigs’ teeth in it one day and then learnt of the local custom of embedding teeth in the bark to cure toothache, a tale recounted by Ruth in Howards End.13

For Forster, Rooksnest was an ancient, almost mystical house, its history ingrained in its very fabric. Yet his mother’s pragmatic attitude towards the house was quite different. Lily had responded to the following advertisement in the Hertfordshire Express on 17 June 1882:

TO BE LET – on lease or otherwise – a SMALL HOUSE, at Rooksnest, Stevenage (unfurnished) containing drawing room, dining room, hall, kitchen, scullery, pantry and larder on ground floor, 4 bedrooms on first floor, good attics, wc etc; excellent cellars. Beautifully situated with extensive views over some of the prettiest parts of Herts. ¼ mile from Stevenage church and 1 ¼ miles from Stevenage station. Rent £45 or with 4 acres of excellent Pasture £55. Stabling if required. For further particulars inquire of Mr Warren, Jun., Builder, Stevenage.14

The cheap rent appealed to Lily, as did the refurbishments to the house, as she wrote to her cousin, Maimie Synnot:

it is a very old gabled house and yet it is perfectly new, it has been refurbished, the inside scooped out – everything nice & pretty as possible – good sanitary arrangements.15

Importantly, it was close to the local train station, and consequently not at all isolated from modern life in London: ‘Stevenage is in Herts., about ¾ hour from Kings Cross, trains run frequently, second class fare 3/7’.16 Rooksnest, therefore, was a rural idyll with modern conveniences (although it did lack running water).

Horsgate in Cuckfield, Sussex c.1910

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.4

Horsgate in Cuckfield, Sussex c.1910

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

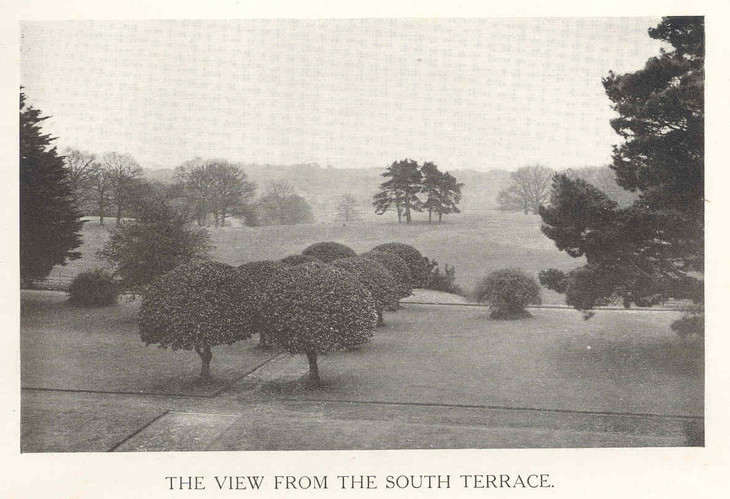

The View from the South Terrace Photograph of Horsgate when it was sold in 1918

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.5

The View from the South Terrace Photograph of Horsgate when it was sold in 1918

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Bevan was also brought up in the countryside, in the Sussex village of Cuckfield.17 Unlike Forster’s ancient home his family estate, Horsgate (fig.4), was purpose built by his father, Richard Bevan, yet its architecture is in the Gothic Revival style conveying a sense of a medieval lineage. The date ‘1865’ written in red brick on the side of the house, however, proudly proclaims its Victorian heritage. Like Rooksnest, then, Horsgate combined modern living with the rural ideal (fig.5).

Bevan’s father was a banker who had settled in Cuckfield around 1861, from where he could easily commute from nearby Haywards Heath on the London to Brighton railway that had opened in 1841.18 He was also a keen huntsman, and his sons inherited a passion for this traditional countryside pursuit (fig.6). Robert’s great-grandfather, Silvanus Bevan III, who was part of a group that set up what is now Barclays Bank in Lombard Street in the City of London, had also owned various country estates, including Riddlesworth Hall, Harling, near Thetford in Norfolk, which he acquired in 1789.19 A family portrait of Silvanus from c.1789, later copied by Bevan’s wife Stanislawa de Karlowska (fig.7), shows the wealthy banker standing with his back to his country estate. His casual pose gives him an air of relaxed authority over both his property and nature itself, in common with other portraits of landowners, such as Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews about 1750 (National Gallery, London).20

Robert Bevan, Herbert Walter Bevan and the Kennelman with Hunting Dogs at Horsgate, Cuckfield, Sussex c.1880s

Photograph, black and white, on paper (photographer unknown)

115 x 177 mm

Inscribed by Robert A. Bevan 'RPB, HWB and Kennelman | with HWB's Harriers | at Horsgate' in pencil on back

Tate Archive TGA 9210/5/4

Fig.6

Robert Bevan, Herbert Walter Bevan and the Kennelman with Hunting Dogs at Horsgate, Cuckfield, Sussex c.1880s

Tate Archive TGA 9210/5/4

Stanislawa de Karlowska 1876–1952

Portrait of Silvanus Bevan III in Front of Riddlesworth Hall, Norfolk, after ?Francis Wheatley c.1920s–30s

Oil paint on canvas

76 x 64 cm

Private collection

© Estate of Stanislawa de Karlowska

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.7

Stanislawa de Karlowska

Portrait of Silvanus Bevan III in Front of Riddlesworth Hall, Norfolk, after ?Francis Wheatley c.1920s–30s

Private collection

© Estate of Stanislawa de Karlowska

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

In his celebrated essay The Country and the City (1973), the cultural critic Raymond Williams shed light on the way that the rural and the urban have typically been set in opposition to one another over the centuries.21 In this next section I explore how Forster and Bevan viewed the city, which serves to illuminate their representations of the country.

*

Forster was born in London in 1879, at 6 Melcombe Place, Dorset Square, which was knocked down in the 1890s to make way for the development of Marylebone Station, its hotel and surrounding flats. Forster lived intermittently in London throughout his life. While his childhood years at Rooksnest formed the basis for the idyllic country house in Howards End, Forster’s experience of teaching at the Working Men’s College on Crowndale Road, Camden Town (intriguingly just in sight of Mornington Crescent where Sickert and Spencer Gore were based from 1905), and his friendship with one of the students, a printer called Alexander Hepburn, inspired the creation of the character Leonard Bast.22

In Howards End we are confronted with a gritty urban interior akin to those in Sickert’s Mornington Crescent paintings when Leonard, who ‘stood at the extreme verge of gentility’, arrives home to his flat, one of a number of new blocks ‘constructed with extreme cheapness’ near Vauxhall, after rescuing his ‘stolen’ umbrella from the West End residence of the upper class Schlegel family.23 As John Carey and Minna Vuohelainen have shown in their studies, the degenerate clerk was a common conceit in stories of the period.24 Forster’s description of Leonard follows this trope, emphasising that his physical degeneracy is the result of urban living:

One guessed him as the third generation, grandson to the shepherd or ploughboy whom civilization had sucked into the town; as one of the thousands who have lost the life of the body and failed to reach the life of the spirit. Hints of robustness survived in him, more than a hint of primitive good looks, and Margaret, noting the spine that might have been straight, and the chest that might have broadened, wondered whether it paid to give up the glory of the animal for a tailcoat and a couple of ideas.25

Leonard’s soon-to-be wife Jacky is described as ‘all strings and bell-pulls – ribbons, chains, bead necklaces that clinked and caught – and a boa of azure feathers hung round her neck, with the ends uneven’, resembling one of the music hall performers painted by Gore or Sickert.26 In her precarious social position, standing with Leonard close to the ‘abyss’ of poverty, she is also reminiscent of the coster-girls painted by these artists.27

Forster’s experience of the nomadic and fluctuating nature of London is echoed in Margaret Schlegel’s experience in Howards End. Margaret is caught up in a style of urban living – visiting concerts and exhibitions, attending meetings and debates – metaphorically likened to a fast-flowing river.28 It is, however, shown to be shallow and without substance when she becomes friends with Ruth Wilcox. Ruth tells Margaret ‘there is nothing to get up for in London’, to which Margaret objects: ‘Nothing to get up for? ... When there are all the autumn exhibitions, and Ysaye playing in the afternoon! Not to mention people.’29 The ‘clever talk’ of Margaret and her friends is, for Ruth, ‘the social counterpart of a motor-car, all jerks’, while Ruth ‘was a wisp of hay, a flower’.30 Margaret begins to realise that she and her friends ‘lead the lives of gibbering monkeys’, but appeals to Ruth saying ‘we have something quiet and stable at the bottom. We really have.’31

Margaret initially feels safe from the modernisation surrounding her, as her family continues to live in her childhood home at Wickham Place, likened to ‘an estuary, whose waters flowed in from the invisible sea, and ebbed into a profound silence while the waves without were still beating’.32 But the narrator later notes that ‘The Londoner seldom understands his city until it sweeps him, too, away from his moorings, and Margaret’s eyes were not opened until the lease of Wickham Place expired’.33 London then changes for her:

In the streets of the city she noted for the first time the architecture of hurry, and heard the language of hurry on the mouths of its inhabitants – clipped words, formless sentences, potted expressions of approval or disgust. Month by month things were stepping livelier, but to what goal?34

She realises that ‘It is impossible to see modern life steadily and see it whole, and she had chosen to see it whole’.35 Urban living, equated with ‘modern life’, then, has created an existence for Margaret that is without stability, tradition or calmness, all of which she craves.

Bevan and Karlowska moved to London just a few years after their marriage in 1900, living at 14 Adamson Road in Swiss Cottage, north London, for the rest of Bevan’s life. Bevan became friends with the artists who would become the Camden Town Group after meeting Gore and Harold Gilman at the first Allied Artists’ Association exhibition in 1908. Possibly inspired by his fellow artists’ depictions of urban life, Bevan began to paint London scenes. The urban experience revealed in Bevan’s paintings, however, contains nothing of the squalor found in Sickert’s Mornington Crescent works or Forster’s description of Leonard Bast’s life.

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

Swiss Cottage c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

61 x 81 cm

Private collection

Photo © Unicorn Press

Fig.8

Robert Bevan

Swiss Cottage c.1912

Private collection

Photo © Unicorn Press

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

The Cab Horse c.1910

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 762 mm; frame: 778 x 906 x 85 mm

Tate N05911

Presented by the Trustees of the Duveen Paintings Fund 1949

Fig.9

Robert Bevan

The Cab Horse c.1910

Tate N05911

a genuine historic interest ... they are precious documents of rapidly disappearing phases of London life. Mr. Bevan is a true heir to Hogarth and Rowlandson, and I have no doubt whatever that his temperamental studies of his own times will be as sought after by future generations as those of Hogarth and Rowlandson are to-day.37

The critic illuminates something here: Bevan’s ability to express a moment in time. While the bright colours, loose handling and dynamic composition of the painting were the modern qualities that most impressed critics of the period, to the viewer today, who is more accustomed to this style, what emerges most emphatically is the historical specificity of the painting.

Bevan’s son noted that the artist later gave up painting cab-horses in favour of horse sales because ‘he was anxious not to be accused of sentimentalising an almost vanished feature of London life’.38 Yet these are not sentimental documents, as another critic, Charles Lewis Hind, noted:

Mr. Bevan sings, in bright colours, stained on rough canvas, the passing of the cab horse. There is no grief, no sentiment, only a strong power of characterisation and vivid colour.39

Bevan’s eye for detail means that every feature in his horse paintings is accurate. But what we are seeing is not just an historical record of the early 1900s; the activity taking place in this painting – two stablemen releasing a horse from the shafts and putting a blanket over it – is a long-standing cultural custom and a staple image of British art history. Walter Bayes described Bevan as like a countryman in town, with a ‘gruff voice and appearance of a fox-hunting squire’.40 Bevan’s connection with the rural conventions of horse-riding and fox-hunting fed into his urban experience, allowing him to see the timeless and traditional in the fleeting and everyday.

*

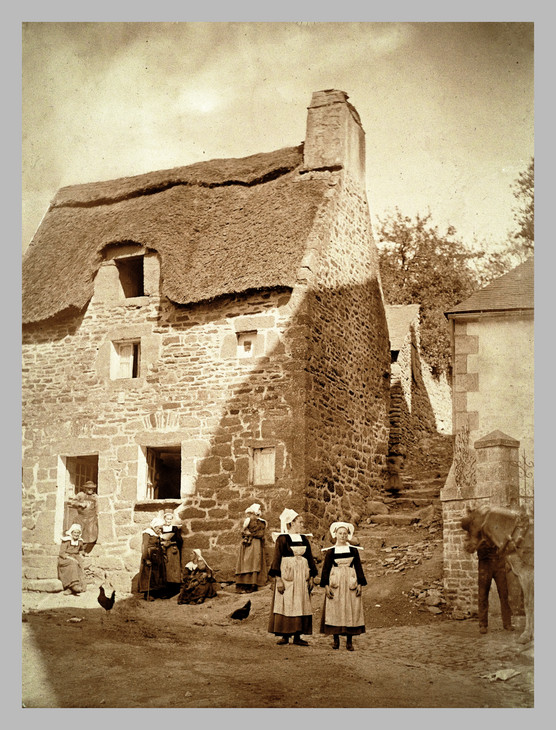

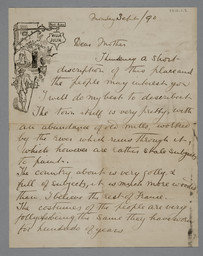

In the 1890s Bevan spent two long periods in the artists’ colony at Pont-Aven in Brittany, sketching the countryside, horses and local community. Pont-Aven was inspirational to many artists because of its apparently authentic, ‘primitive’ culture. As its most famous visitor, Paul Gauguin, wrote to a friend:

You’re a Parisian, but give me the country. I love Brittany. I find a wildness and a primitiveness there. When my wooden shoes ring out on its granite soil, I hear the muffled, dull and powerful note I am looking for in my painting.41

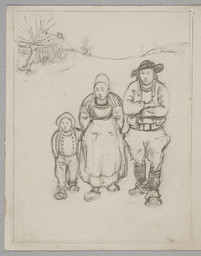

While Bevan’s view of Pont-Aven was less dramatic, he was still interested in the customs of the Breton people in a similar fashion to an ethnographer. As he wrote to his mother in 1890 (fig.10): ‘The costumes of the people are ... the same they have worn for hundreds of years’; ‘Nothing but Breton is talked amongst the people, most of them knowing very little French, some none at all.’ The authentic experience was also important: ‘A certain number of English come this way but Thank Heavens we are quite free from the most objectionable sort of tourist, and I suppose as the winter comes on we shall see nobody in the way of visitors.’42 Bevan owned photographs of Pont-Aven (fig.11), which he may have taken himself, that document the customs of the Breton people, possibly to serve as inspiration for future artworks.

As in his later London paintings, Bevan’s Pont-Aven works emphasise the traditional as emblematised by local custom. Ploughing in Brittany 1893 (Tate T00250, fig.12) shows two Breton peasants in local costume ploughing a field. The pink of the soil and the blue of the trees give the work a modern flavour, and the drawing is stylised in the manner of Vincent van Gogh. The movement from right to left strengthens this portrayal of labour. The white of the horses is echoed in the female figure’s cap and in the distant house. Through this carefully balanced and rhythmic composition, we survey the whole life of this couple: work and home. This is land that has been tilled in the same way before and will be again, underlining continuity from past to present to future, akin to the realist portrayal of labouring peasants in such works as Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners 1857 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris).43

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

Ploughing in Brittany. Verso: Study of a Woman 1893

Crayon and watercolour on paper

support: 256 x 352 mm

Tate T00250

Purchased 1959

Fig.12

Robert Bevan

Ploughing in Brittany. Verso: Study of a Woman 1893

Tate T00250

Robert Bevan and Stanislawa de Karlowska standing outside Lytchetts in Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

Fig.13

Robert Bevan and Stanislawa de Karlowska standing outside Lytchetts in Devon c.1917–18

Courtesy of Patrick Baty

From 1912 until his death in 1925 Bevan spent most of his summers in the hills on the border of Devon and Somerset. He was introduced to the area when invited by Harold Bertram Harrison to stay at his farm estate, Applehayes. Bevan later rented a cottage, Lytchetts, on Hart’s Farm in nearby Bolham Water for the summers of 1916–19 (fig.13), then stayed at Gould’s Farm, Luppitt, in 1920, and later bought a cottage, Marlpits, near Luppitt Common.

Although his initial visits to Applehayes had been in the company of friends, later trips to the area were generally undertaken alone, although his wife and children did sometimes accompany him. A local farmer’s daughter, Anne Chard, described him:

Some of us can remember, during childhood, meeting a solitary gentleman tramping miles by foot across the Blackdown Hills and Luppitt areas. He carried either a sketchbook and pencil or paints and easel, tucked under his arm.44

A photograph of Bevan out sketching alone in the countryside adds to this impression (fig.14). But during these visits he also observed the customs of rural life by undertaking them himself. As Anne described:

At Lytchetts, Mr Bevan mostly fended for himself, cutting wood, drawing water and cooking. A neighbour laundered and ironed his clothes and starched his collars. When at home in his new, dry cottage he preferred to wear sabots, which we thought peculiar. We showed him where to pluck fresh watercress and where to find the largest filbert nuts.45

The property details for Marlpits (fig.15), which was sold after his death, states that the ‘Garden [is] newly stocked with fruit bushes, etc.’, there are ‘Good bearing apple trees’, ‘Water is obtained from a good well and is plentiful’ and ‘The owner of the cottage can also pasture a cow or horse on the common, which is far reaching. There is also the right of cutting bracken and, I believe, of shooting rabbits.’46 Bevan was therefore quite self-sufficient in the countryside. He rarely gave the impression of being an artist, as his son described:

he rather relished looking like a man who had to do more with horses and hounds than with canvas and paint. The brim of his bowler hat was flattened, his overcoats had little buttons at the back of the waist; his suits were grey, and in town and country the ties round his invariable stiff white collars were thick blue bows with white dots. He always looked at home at Tattersall’s and other places where the horse took the centre of the stage. He looked neither like a bohemian nor a business-man.47

Bevan’s admiration for the ordinary labourer – be they a stableman, auctioneer or farmer – to the extent of dressing and working like them, is evident in his paintings, such as the worker in Dunn’s Cottage 1915 (fig.16). Bevan did not see the countryside as an opportunity for sentimental, picturesque views, but as a place of engagement and continuity, where people worked on their land.

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

Dunn’s Cottage 1915

Oil paint on canvas

482 x 558 mm

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.16

Robert Bevan

Dunn’s Cottage 1915

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

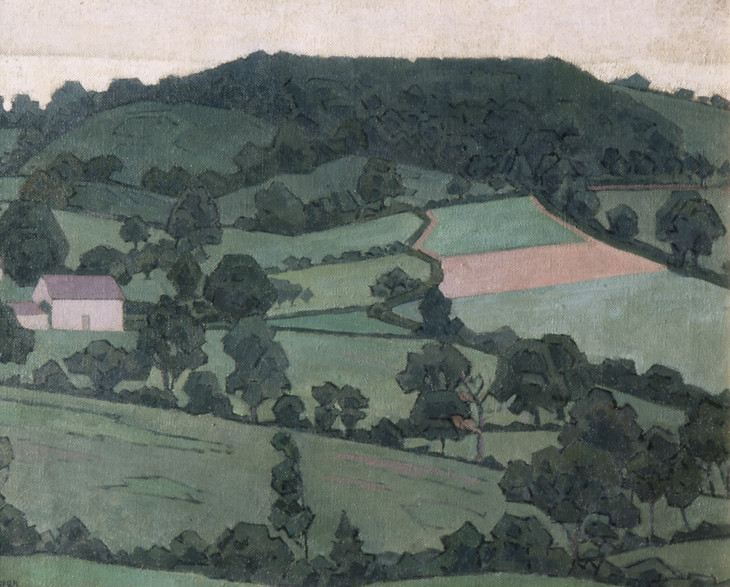

Rosemary, La Vallée 1916

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 493 x 615 mm

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove H1988.14

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Fig.17

Robert Bevan

Rosemary, La Vallée 1916

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove H1988.14

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

In Rosemary, la Vallée 1916 (fig.17) Bevan uses a modern, geometric style to characterise natural forms, such as the trees and undulations of the land. There are no quaint peasants on the hills, as would often be found in picturesque genre paintings from previous centuries. Bevan presents the scene in an unadorned and clear style, emphasising the modulations in colour over narrative content. Yet as with Ploughing in Brittany (fig.12), made over twenty years previously, Rosemary, la Vallée emphasises home – as represented by the white house on the left – with work – as represented by the farmed fields in the centre. A third component, the hills and woods, is also key – it tells us that this is an ancient view and one that is unspoilt, in Bevan’s opinion, as he treats all of these components equally. Bevan’s use of a post-impressionist geometric style also gives the scene a strong, enduring character in contrast with the impressionist focus on atmosphere over subject.

Margaret Schlegel shares Bevan’s view, as she says:

In these English farms, if anywhere, one might see life steadily and see it whole, group in one vision its transitoriness and its eternal youth, connect – connect without bitterness until all men are brothers.48

On walking to Howards End, Margaret finds that ‘At the church the scenery changed. The chestnut avenue opened into a road, smooth but narrow, which led into the untouched country.’ The land is ‘neither aristocratic nor suburban’ and ‘Though its contours were slight, there was a touch of freedom in their sweep’.49 The sense of freedom engendered by ‘untouched country’ is crucial to Forster’s vision: it is in the countryside where the individual is liberated. This is primarily demonstrated by Helen Schlegel’s move to Howards End following her pregnancy. To have brought up a child as an unmarried woman in London would have been difficult, and would have made her a social outcast. In the country, on the other hand, she is free to bring up her child as she desires. Forster’s implication therefore is that the countryside is the natural place for child-rearing, equating Helen’s fertility with the fecundity of nature. It is also a place of sexual freedom more generally. Forster experienced this in his own life when visiting Edward Carpenter who, unlike Forster, lived in an openly homosexual relationship out in the countryside. Freedom from stringent social constraints is therefore intimately linked, for Forster, with rural life.

But this was not a universal experience. As Ford Madox Ford wrote in 1906, the common yearning for a ‘return to the land’ was only really felt by

the comparatively well-to-do. For the poor and the working-classes of the towns never really go back. One in five hundred may be attracted by a ‘good job’, but perhaps not one in a hundred goes seeking, however unconsciously, a country spirit.50

Leonard Bast is ‘one in a hundred’ in his desire to ‘get back to the earth’.51 But he does not do so in order to connect with his rural past; in fact it is a ‘shameful’ secret that his grandparents ‘were just nothing at all ... agricultural labourers and that sort’.52 Rather he has read books that evoke the individual’s freedom when walking in the countryside and desires the romantic escape of fiction, thinking ‘What’s the good – I mean, the good of living in a room for ever? There one goes on day after day, same old game, same up and down to town, until you forget there is any other game.’53 But Leonard’s freedom only lasts one night, as he later says after losing his job, ‘Walking is well enough when a man’s in work’ but now ‘I see one must have money’.54 His poverty ties him to the city and to his responsibilities, and the countryside ultimately renders him hungry, tired and bored.

As with Bevan’s view of labourers, Margaret finds dignity in the rural working classes. The charwoman for Howards End, Miss Avery, is belittled by the Wilcoxes, but Margaret realises that ‘Here was no maundering old woman. Her wrinkles were shrewd and humorous. She looked capable of scathing wit and also of high and unostentatious nobility.’55 Miss Avery, as representative of rural folk, is noble because of her straightforwardness, in keeping with Margaret’s view of the unmannered and uncluttered rural existence as opposed to the modern urban way of life. However, this view contrasts quite sharply with her poor perception of the Basts as representatives of the aspiring urban working classes.

When Margaret first meets Leonard she finds ‘his class was near enough her own for its manners to vex her’.56 Upon meeting him again, she finds this clerk ‘uneasily familiar’ and muses that ‘She knew this type very well – the vague aspirations, the mental dishonesty, the familiarity with the outside of books. She knew the very tones in which he would address her.’57 Leonard’s pretensions to culture and class aspiration are what repel Margaret; he does not fit in with the cultured life of the city or the ‘simple life’ of the country, as perceived and lived by the upper classes.

On each occasion that the Basts enter the countryside they are out of place. When first visiting her fiancé Henry Wilcox’s ‘genuine country house’,58 Oniton Grange, Margaret proclaims ‘I love Shropshire. I hate London. I am glad that this will be my home ... what a comfort to have arrived!’59 When the Basts appear there, having been ferried up from London by Helen because Leonard has lost his job, Margaret realises that she finds Jacky ‘repellent’ and ‘had felt, when shaking her hand, an overpowering shame’, smelling ‘odours from the abyss’.60 Leonard’s final visit to the countryside – to Howards End – ends in his death. The night before, Margaret had felt that ‘The peace of the country was entering into her’,61 and even after Leonard’s murder by Charles Wilcox, she and her sister are able to ‘Let squalor be turned into tragedy’ as she ‘could not shake her belief in the eternity of beauty’ as given to her by the rural spirit.62 Margaret wants to help Leonard, but she cannot help being repelled by the ‘odour’ of his urban poverty, the product of his family’s migration from the country to the city.

*

After the Second World War, Forster himself was torn between his love of the country and its persistent sense of continuity and the needs of the mass of humanity when bombing had made many homeless and new towns needed to be built. Describing the neighbourhood of Rooksnest, he said ‘It must always have looked much the same. I have kept in touch with it, going back to it as to an abiding city and still visiting the house which was once my home, for it is occupied by friends.’63 But the satellite town has finished the local people off ‘as completely as it will obliterate the ancient and delicate scenery’.64 Although he realises that people need to be housed:

I cannot free myself from the conviction that something irreplaceable has been destroyed, and that a little piece of England has died as surely as if a bomb had hit it. I wonder what compensation there is in the world of the spirit for the destruction of the life here, the life of tradition.65

In weighing up his desire for an unspoilt countryside alongside his acknowledgment of housing needs, Forster concludes that ‘I cannot equate the problem. It is a collision of loyalties.’66

Perhaps something of this collision of loyalties can also be found in Bevan’s paintings: although he does not differentiate between agricultural land and unspoilt country in the same way as Forster in Howards End, he endows his representations of working people with nobility even as he avoids individualising them. Unlike Gore, Sickert and Gilman, who tried to evoke the personalities of the people in their paintings, Bevan’s figures are mostly anonymous, seen from a distance, often without facial features. They are representative of certain social types, evoking certain traditions. To introduce individual personality to both his urban and rural figures would be to upset the timelessness that he is interested in capturing. As Frank Rutter argued in 1911: ‘Mr. Bevan has “remained an Englishman,” and one day his countrymen will recognise in him the true heir and logical evolution of the great national tradition of Hogarth, Rowlandson, and Gillray.’67

The narrator in Howards End comments that in the Georgian period:

To speak against London is no longer fashionable. The earth as an artistic cult has had its day, and the literature of the near future will probably ignore the country and seek inspiration from the town.68

Forster laments that the country is no longer of interest. But for Bevan rural customs were not divorced from his ordinary, everyday reality. While he was keen to reject outmoded conventions of painting – as shown by his use of bright colours and experimental brushwork – his subjects reveal a continuity with traditions of rural labour. He found the rural in the urban and therefore felt at home in either setting in a way that the characters in Howards End could not.

Notes

E.M. Forster, diary entry for 27 January 1908; quoted in Oliver Stallybrass, ‘Editor’s Introduction’, in E.M. Forster, Howards End, Abinger edn, Edward Arnold, London 1973, pp.x–xi. The quote in the essay title is from E.M. Forster, Howards End, introduction by David Lodge, Penguin, London 2000, p.229.

For more on Forster, see Wendy Moffat, E.M. Forster: A New Life, Bloomsbury, London 2010 and P.N. Furbank, E.M. Forster: A Life, Secker and Warburg, London 1977. See also the Forster Papers at King’s College Cambridge, http://janus.lib.cam.ac.uk/db/node.xsp?id=EAD%2FGBR%2F0272%2FPP%2FEMF .

E.M. Forster, Marianne Thornton, Edward Arnold, London 1956, p.269; quoted in Stallybrass 1973, p.vii.

William Ratcliffe and Harold Gilman both lived in Letchworth, and Spencer Gore spent a productive few months there in 1912 painting some of his most advanced work. James Bolivar Manson and later Ratcliffe lived in Hampstead Garden Suburb.

See Ashby 1991, p.44 and Forster 2000, p.61. Forster was also surprised to learn after he had written Howards End that Rooksnest had once been the farm of a family called Howard for over 300 years.

For more on Bevan, see Frances Stenlake, Robert Bevan: From Gauguin to Camden Town, Unicorn Press, London 2008 and Frances Stenlake, From Cuckfield to Camden Town: The Story of Artist Robert Bevan, Cuckfield Museum, Cuckfield 1999.

John Simkin, ‘London and Brighton Railway’, Spartacus Educational, http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/RAbrighton.htm , accessed August 2010.

The Bevan Family Letters, http://bevan.rth.org.uk/Family-history/more-about-the-bevans , accessed 15 August 2010.

Reproduced at The National Gallery, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/thomas-gainsborough-mr-and-mrs-andrews , accessed 15 August 2010.

Raymond Williams, The Country and the City, Hogarth Press, London 1973. For more on ruralism in this period, see Jan Marsh, Back to the Land: The Pastoral Impulse in England, from 1880–1914, Quartet Books, London 1982; Simon Grimble, Landscape Writing and the ‘Condition of England’, 1878–1917: Ruskin to Modernism, Edwin Mellen, Lampeter 2004; David Peters Corbett, Ysanne Holt and Fiona Russell (eds.), Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past, 1880–1940, Yale University Press, New Haven 2002; Lisa Tickner, ‘Augustus John: Gypsies, Tramps and Lyric Fantasy’, Modern Life & Modern Subjects: British Art in the Early Twentieth Century, Yale University Press, New Haven 2000, pp.48–77; and Ysanne Holt, British Artists and the Modernist Landscape, Ashgate, Aldershot 2003.

Stape 1993, p.26. For more on Forster at the Working Men’s College, see P.N. Furbank, E.M. Forster: A Life, vol.1, Secker and Warburg, London 1977, pp.174–6.

John Carey, The Intellectuals and the Masses: Pride and Prejudice among the Literary Intelligentsia, 1880–1939, Faber and Faber, London 1992, p.62. Minna Vuohelainen, ‘The Clerk from Walham Green: The Centrality of the Suburban in Richard Marsh’s The Adventures of Sam Briggs (1904–16)’, unpublished paper delivered at Representations of London in Literature: An Interdisciplinary Conference, Institute of English Studies, University of London, 9 July 2010.

For more on the use of water as a metaphor for change in Howards End, see Anthony Lake, ‘“London is a Muddle”: E.M. Forster and the Flâneur’, Literary London, vol.6, no.2, September 2008, http://www.literarylondon.org/london-journal/september2008/lake.html , accessed 15 February 2010.

Reproduced at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, http://www.barber.org.uk/502.html , accessed 15 October 2010.

Charles Lewis Hind, ‘Hedgehog Art. At the Stafford & Carfax Galleries’, Daily Chronicle, 8 July 1911.

Robert Bevan, letter to Laura Bevan, September 1890, Villa Julia, Pont-Aven, Tate Archive TGA 9210/1/2.

Reproduced at the Musée d’Orsay, http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/index-of-works/notice.html?no_cache=1&nnumid=000342&cHash=208fcd6ac2 , accessed 17 November 2010.

Ford Madox Ford, The Heart of the Country: A Survey of a Modern Land, Alston Rivers, London 1906, p.58.

E.M. Forster, The Challenge of our Time, BBC radio broadcast, May 1946; quoted in Ashby 1991, p.137.

Helena Bonett is Research Coordinator, Tate.

How to cite

Helena Bonett, ‘‘In these English farms, if anywhere, one might see life steadily and see it whole’: Representations of the Countryside in the Paintings of Robert Bevan and E.M. Forster’s Howards End’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www