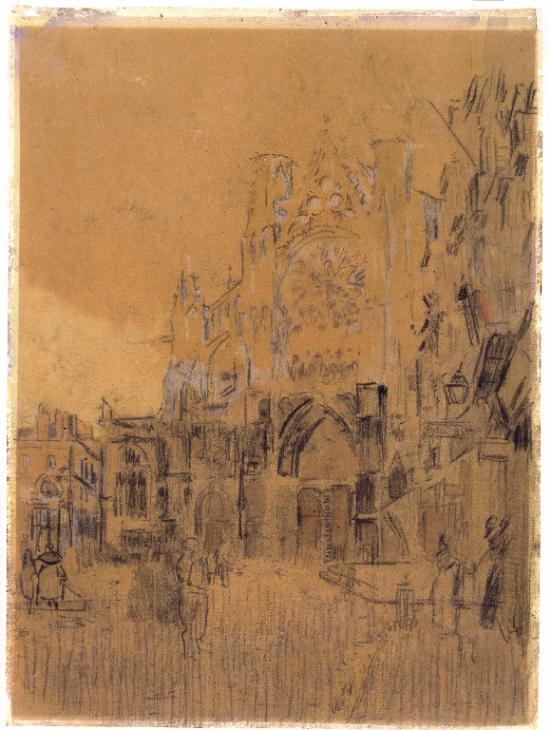

Walter Richard Sickert Dieppe, Study No. 2; Facade of St Jacques c.1899

Walter Richard Sickert,

Dieppe, Study No. 2; Facade of St Jacques

c.1899

This drawing of the fourteenth-century Gothic cathedral of St Jacques in Dieppe shows its western façade from the Rue Saint-Jacques, with part of the adjacent Hôtel du Commerce dwarfed in the left background. The church was Sickert’s most frequently depicted subject. This reproduced image, made using typewriter carbon paper, may have been part of a series of tinted ‘commercial drawings’ Sickert made to capitalise on his repertoire of Dieppe views. Watercolour washes emphasised the lighting of the sky and buildings cast in shadow below, as well as certain architectural details, but are now difficult to apprehend owing to the paper’s discolouration.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Dieppe, Study No.2; Façade of St Jacques

c.1899

Carbon paper tracing and watercolour on paper

323 x 234 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black bottom right

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05094

c.1899

Carbon paper tracing and watercolour on paper

323 x 234 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black bottom right

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05094

Ownership history

Possibly acquired by Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck (1863–1931), London, from the Carfax Gallery, London, 1913; inherited by his wife, Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, by whom bequeathed to Tate Gallery 1940.

Exhibition history

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (17, reproduced).

References

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, pp.67, 103.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.632.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London 1973, no.120.6, pp.322–3.

2001

David Peters Corbett, Walter Sickert, London 2001, pp.21, reproduced fig.15.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.134.5, p.244.

Technique and condition

Dieppe, Study No.2; Façade of St Jacques is a carbon paper tracing with watercolour on wove paper. The paper is machine-made, lightweight and the edges are cut straight. Unlike that used for The Piazzetta and the Old Campanile, Venice (Tate N03810), the paper is of poor quality made with wood-pulp fibres which have weakened and discoloured. The edges of the paper sheet have been protected by a window mat and in these protected areas the initial cream colour of the paper and original tone of the watercolours are preserved.

Sickert used carbon paper to create his image, which consisted of a thin sheet of paper coated on one side with pigment and was designed for duplicating original documents. The duplicate was made by placing the carbon paper ink side down on a blank sheet of paper. The original drawing was placed face-up on the uncoated side of the carbon paper and a duplicate made by tracing through the original. The pressure applied via tracing transferred the image onto the blank sheet of paper. The image was created using two different coloured sheets of carbon paper, black and purple. Along the top edge of the paper there are a number of pinholes and it is possible that Sickert used pins to register the different papers during the process of duplication. Watercolour washes were applied after the drawing and were limited to the sky and to emphasise certain architectural details. Owing to the discoloured appearance of the paper it is difficult to appreciate the aesthetic effect of these coloured washes as they would have originally appeared.

Kate Jennings

June 2005

How to cite

Kate Jennings, 'Technique and Condition', June 2005, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Dieppe, Study No.2; Façade of St Jacques c.1899 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, September 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

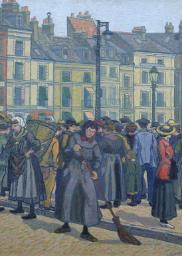

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Façade of St Jacques, Dieppe c.1899–1900

Oil paint on canvas

559 x 482 mm

Whitworth Art Gallery, The University of Manchester

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Whitworth Art Gallery, The University of Manchester

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

The Façade of St Jacques, Dieppe c.1899–1900

Whitworth Art Gallery, The University of Manchester

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Whitworth Art Gallery, The University of Manchester

Sickert once described Dieppe as his ‘goldmine’ which provided him with ‘a little decent comfort’.6 Following the advice of Ernest Brown of the Fine Art Society who proposed that ‘watercolours sold always like fire’, the artist seems to have tried to capitalise on his repertory of Dieppe views by making ‘tinted drawings’ of many of the same subjects.7 The art historian Wendy Baron has described these works on paper as ‘commercial drawings’, saleable products which were traced from a primary document and quickly worked up into different permutations of the same theme.8 This view of St Jacques is a transfer drawing made using typewriter carbon paper with watercolour applied over the transferred design. It is not known whether this unusual use of media constituted an innovative form of printmaking (similar to monotype) or whether the artist was simply experimenting with ways of manufacturing multiple images. However, Sickert may have been influenced by Edgar Degas’s practice of making coloured variations from multiple traced images (see the discussion for Tate N03810).

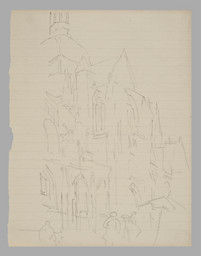

There is a defined series of five other variations related to the subject matter and composition of Tate’s work, all of which are unique in colouring and execution.9 One example is The Façade of St Jacques (British Council, London),10 which in turn reflects the arrangement of a squared-up drawing, St Jacques, Dieppe (Hatton Gallery, University of Newcastle upon Tyne),11 with the vista enclosed by buildings on the left. Tate’s drawing, however, which is open on the left, appears to have evolved from an un-squared preparatory sketch, Dieppe (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa).12 This study contains the same figurative arrangement across the foreground: the couple on the left in front of the kiosk; the small group loitering on the pavement on the right; and the small collection of figures in between, including a pair of nuns and a man wearing a flat cap. In the Tate drawing the nuns have been reduced to indistinct dark outline forms. Other examples of the carbon tracing technique in Tate’s collection are The Piazzetta and the Old Campanile, Venice c.1901 (Tate N03810) and Sketch for ‘The Statue of Duquesne, Dieppe’ c.1902 (Tate N05096).

An artistic precedent for paintings and drawings of St Jacques’s western façade can be found in the work of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century topographers, such as David Roberts (1796–1864) (Museum of New Zealand),13 and John Sell Cotman (1782–1842) who made a detailed drawing (Birmingham City Art Gallery) which was later published in Architectural Antiquities of Normandy (1822).14 The French impressionist painter Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) also painted the church during a visit to Dieppe in 1901 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris).15 For other paintings of Dieppe by Sickert see Café des Tribunaux, Dieppe (Tate N03182) and Les Arcades de la Poissonnerie (Tate N05045).

Nicola Moorby

September 2009

Notes

Reproduced ibid., no.130.10 and Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992 (30).

Ibid., no.134; reproduced at British Council, http://collection.britishcouncil.org/collection/artist/5/17966/object/44158/ , accessed September 2009 (reproduced wrong way round).

See Baron 2006, no.132; reproduced in Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 2004 (3.02).

Baron 2006, no.133.2; reproduced at http://cybermuse.gallery.ca/cybermuse/search/artwork_e.jsp?mkey=4190 , accessed September 2009.

See a watercolour in the Museum of New Zealand, http://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/objectdetails.aspx?oid=39469&page=15&imagesonly=true , accessed September 2009.

Related biographies

Related catalogue entries

Related archive items

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Dieppe, Study No.2; Façade of St Jacques c.1899 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, September 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www