Walter Richard Sickert Roquefort c.1919-20

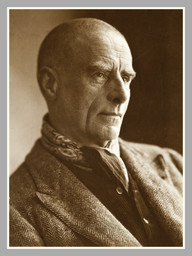

Walter Richard Sickert,

Roquefort

c.1919-20

This work is part of a series of still lifes that Walter Sickert painted in 1919–20 at his home in Envermeu, near Dieppe in northern France. It shows a rustic wooden kitchen table from above, upon which a plate of Roquefort cheese rests under a glass lid, the handle of a knife extending from beneath it. A single glass of wine has been poured out from the long-necked green bottle standing by the bare wall. The series seems to commemorate the simple French domestic life he shared with his wife Christine at this time, despite the material hardships caused by the First World War, from which Europe was still recovering.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Roquefort

c.1919–20

Oil paint on canvas

409 x 328 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert.’ in brown paint bottom left

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

N03847

c.1919–20

Oil paint on canvas

409 x 328 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert.’ in brown paint bottom left

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

N03847

Ownership history

Goupil Gallery, London, March 1920 (19), where bought by the Contemporary Art Society 1920; presented to Tate Gallery 1924.

Exhibition history

1920

Paintings and Drawings by British and Foreign Artists, Goupil Gallery, London, March 1920 (19).

1923

Contemporary Art Society Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings, Grosvenor House, London, June–July 1923 (114).

1938

La Peinture anglaise XVIIIe & XIXe siècles, British Council, Palais du Louvre, Paris 1938 (116, as ‘Nature morte’, reproduced).

1957

Sickert: An Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings and Prints, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, August–September 1957 (56).

1977–8

Sickert, (Arts Council tour), Ferens Art Gallery, Hull, December 1977–January 1978, Glasgow Art Gallery, February–March 1978, Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, April–May 1978 (50, reproduced p.30).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (21, reproduced p.30).

References

1927

J.B. Manson, ‘Walter Richard Sickert, A.R.A.’, Drawing and Design, no.3, 1927, p.3.

1955

Anthony Bertram, Sickert, London and New York 1955, reproduced pl.40.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, p.102.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, pp.624–5.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, p.159, no.377.

1976

Denys Sutton, Walter Sickert; A Biography, London 1976, p.195.

1988

Richard Shone, Sickert, Oxford 1988, p.71.

2005

Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, p.512.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.502.

Technique and condition

Walter Sickert purchased a pre-primed canvas from Paul Foinet Fils, a well-established Parisian colourman who had premises on the Rue Brea. The linen canvas has a fine open weave and was prepared with an off-white primer of lead white with traces of iron oxides and extenders, probably in oil. The canvas was removed from its original stretcher after painting and cut down to fit, although a very small amount of the composition, now 2–3 mm, extends onto the right-hand tacking margin. There is an inscription on this margin which may relate to the original stretched canvas, reading 19¾ x 16 inches.

Sickert painted directly on the canvas with no preliminary drawing. The subject was presumably observed from life and the painting executed ‘alla prima’ (see Tate N03182). Unusually, Sickert has not modified the ground and any initial sketching is very thin and tentative, perhaps just to delineate the main elements. He has then painted individual objects, the glass, the bottle, the cover, the cheese, the knife and the table surface separately, using direct local colour for the painting. The technique is minimal, wet-in-wet and with little preparation or working. He has applied clearly visible brushstrokes often isolated from other strokes by the white priming but sometimes merging wet-in-wet. There is little or no reworking and no deliberate merging or sweetening (passing a dry soft-haired brush across the surface to blend colours and soften brushwork). His colour range is greens and warm browns mostly mixed with white for opacity except for where deeper colour and tonal contrast was required. The white priming is strongly retained and the colours have consequently not sunk and are well saturated by the varnish. Soon after painting, the work was stacked with other canvases, face to back, probably unstretched leaving a negative impression of canvas texture that is clearly visible in areas of squashed wet impasto and small pieces of canvas and other material lodged in the surface.

Stephen Hackney

August 2004

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', August 2004, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Roquefort c.1919–20 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, January 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Roquefort is one of a series of still life subjects that Walter Sickert painted at home in Envermeu in Normandy between 1919 and 1920. The painting comprises the top of a plain wooden table seen slightly from above, upon which sits a plate of Roquefort cheese covered with a circular glass lid. A bone or wooden handled knife lies on the table partially hidden under the plate. The composition is completed by a bottle of white wine with one glass poured out beside it.

During the summer months Sickert liked to escape from London and take a break from his exhausting schedule of writing, teaching and exhibiting by painting landscapes in Dieppe. In 1912, he and his second wife Christine found a permanent base at Envermeu, a village around ten miles south-east of Dieppe, ‘ideal, sheltered & sunny’.1 The Villa d’Aumale was ‘a beautiful little house, nice proportions’ with separate, quiet work rooms which Sickert used as a studio.2 The house and location were well suited to his needs, being within easy reach of Dieppe and the Channel but also somewhat secluded, situated in a charming valley close to the picturesque forest of Arques. He wrote to his friend Ethel Sands:

You can’t think the change it is after the noisy streets of Dieppe working enervated by a crowd passing or shaking hands, perfect hell for the nerves, now sitting in perfect solitude in a farm yard or field with my work & my own thoughts.3

The Sickerts sojourned at the Villa d’Aumale during the summers of 1913 and 1914 and intended to repeat this pattern each year, but the outbreak of war interrupted their regime and they were not able to return for five years, the longest period Sickert had spent away from France in his adult life. In 1919 they made plans to settle near Dieppe permanently. Sickert was finding it increasingly expensive to live in London, and wished to be able to paint unhindered by his busy city lifestyle and to complete work in his own time without being pressed by his dealers. To this end, in early 1920 Christine bought the Maison Mouton at Envermeu, ‘an old house constructed of timber & cowpats ... which has been a gendarmerie, a horse-dealer’s, an Inn & has till Easter a farmer as tenant’.4 Sickert immortalised the moment of purchase in a painting, Christine Drummond Sickert, Née Angus, Buys a Gendarmerie 1920 (whereabouts unknown).5 For him it represented liberation from the pressures of London:

I am very glad we have got a house. It is the only chance for me to get enough rest to enable me to work ... I may go on for years here where I can get up early & paint all daylight with no tubes & no trams & no one saying anything suddenly ... Also what is rather convenient is that dealers cannot drop in before the paint is dry.6

A further related picture is A French Kitchen c.1919–20 (Getty Museum, Malibu, California),7 which may depict Christine in the kitchen at Envermeu.

Food and drink were a source of pleasure in Sickert’s life and he particularly relished French cuisine, which he managed to find even when living in London during the First World War. In a letter to Sands he described his own efforts at cooking ‘déjeuner’ despite the strictures of rationing: ‘Today for instance each a slice of grilled salmon at a shilling head, a salad of mache with 2 hard-boiled eggs a snip of gruyere half a tumbler of Sauterne a demi-tasse of such coffee ground in the old-fashioned French machine screwed to the wall.’8 Certain foods must have been easier to come by in the agricultural regions of France after the war and Sickert, who employed a cook at Envermeu, reported gleefully to Sands, ‘We live on prime geese, venison & red wine’.9 He sometimes compared the preparation of paint to that of cooking and relished the materiality of both.10

Still life

Sickert rarely painted still life subjects, and the art historian Wendy Baron has described the 1919–20 series, painted either at the Villa d’Aumale or at the Maison Mouton, as a reflection of ‘his sense of well-being, the happy acceptance of his domestic life during the brief time he and his wife enjoyed together in their French home after the privations of the war’.11 The series of paintings depict simple arrangements of typically provincial French food and drink, and include Lobster on a Tray (Kirkcaldy Museum and Art Gallery),12 The Makings of an Omelette 1919 (Phillips Art Gallery, Washington DC),13 Cherries in a Colander 1919–20 (on long term loan to Cartwright Hall Art Gallery, Bradford),14 Three Herrings c.1919 (private collection),15 and Asparagus (Tatham Art Gallery, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa).16 There are also several still life drawings.17 One of these Still Life – Cheese and Wine (private collection),18 in black chalk and pen heightened with white, is related to Roquefort. Almost identical in composition and inscribed ‘Envermeu’, the drawing may be a preparatory sketch for the painting, but is also so complete that it may have been intended as a work in its own right. The application of the oil paint for Roquefort, in dry thin layers, suggests that the painting might have been made swiftly and directly from this drawing, or from the still life itself. The immediacy of the paint’s appearance, however, is belied by the structured nature of the composition, which follows, perhaps consciously, the habit of the French painter Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699–1779) in placing a knife, which leads the eye into the composition.

Historically, the genre of still life painting had been used as a visual warning against the transience of human existence and the shallowness of sensual pleasures. Sickert’s paintings seem, however, to have been intended as a life-affirming celebration of the simple pleasures of eating and drinking, and a personal statement regarding the intrinsic value of the life he had chosen to lead. The objects and surroundings of the arrangement are suggestive of a rustic French lifestyle. The French traditionally eat this salty blue cheese made from sheep’s milk at the end of a meal with a dessert wine such as Sauternes. The bottle in the painting is rather tall and slightly misshapen and does not bear a label, which suggests that the wine is locally or home produced. The simple tabletop clearly shows the patterns of the wood grain and the background appears to be a plain stone or whitewashed wall. The glass surfaces reflect the shaft of sunlight which appears to shine in from the left of the picture and which casts a broken shadow on the wall behind the bottle. The spirit of the still life is conducive with Sickert’s perceived need to escape from his urban existence and adopt a simpler, healthier and authentically ‘French’ lifestyle. The painting is especially rich in the sense of a yearning to touch the glass lid, the knife and the glass. As a series, the still life paintings construct a fantasy of rustic village life based on good food, fresh air, local produce and unaffected simplicity.

The irony of that expression is that it was an idyllic construct. In contrast to their healthy, bountiful images, the paintings were in reality made at a time of relative hardship and struggle. Although food was more plentiful in France in the years following the First World War, the period was one of recuperation and recovery rather than prosperity. The daily business of housekeeping in a small village such as Envermeu would have involved a certain amount of hardship and labour. The winter of 1919–20 was particularly severe and Christine, who had fragile health, was ill with tuberculosis. She recovered sufficiently in the spring to supervise the move to the Maison Mouton but she deteriorated rapidly over the summer and autumn and eventually died in October 1920. Her death signalled the end of Sickert’s desire to live in France. Having once longed for the life in Envermeu it now became abhorrent to him, associated as it was with his grief. He also yearned to return to city comforts and entertainments. He wrote to Christine’s younger sister, Andrina Schweder (née Angus):

I know perfectly well that, as long as I have any health, I shall work, as I do now, from 10 to 4 by daylight and 4 to 7 by artificial light, and frequently draw at music halls from 8 to 11. All these things I can’t do now at Envermeu. When Christine was alive I loved the landscapes there, because they seemed to belong to her, and the still lifes, etc. because they were seen in her house ... But I can’t bear the sight of those scenes now. They are like still-born children.19

Sickert moved out of the Maison Mouton at the end of 1920 and stayed at a number of addresses in Dieppe. Having completed several planned alterations and improvements to his property he subsequently made over the house by deed of gift to Andrina Schweder (later Tritton), the daughter of Christine’s younger sister. In 1922 he moved back to live in London. Roquefort and the other still life paintings from this period remained a personal memento mori for that brief period of his life.

Ownership

Roquefort was purchased by the Contemporary Art Society in 1920, within a year of being painted, at a time when the Tate Gallery possessed three paintings by Sickert, two given already by the Contemporary Art Society and one by Sylvia Gosse. The CAS committee then included Sickert’s friends and patrons Roger Fry, Edward Marsh and Lord Henry Bentinck, who was the chairman. The painting was given to the Tate in 1924 at the same time as his famous painting Ennui (Tate N03846). In 1927, James Bolivar Manson, then assistant to the director of the Tate, wrote a panegyric essay on Sickert, whom he knew from Camden Town Group days. Regarding Roquefort he wrote:

The tones are so just, the relationships so perfect, that it produces the effect of a satisfying feeling of beauty. And it has quality. It is painted with style: that is to say it is simple and direct, displaying an exact understanding of what is required: that and no more. It conveys that sense of inevitability which is characteristic of all perfectly done things; the feeling that they could not properly be done in any other way.20

Nicola Moorby

January 2005

Notes

Reproduced in Marjorie Lilly, Sickert: The Painter and his Circle, London 1971, pl.19; Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.541.

Helen Lessore, Walter Sickert 1860–1942: Sketch for a Portrait, 10 February 1961, BBC recording LP 26655, Side 2.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related archive items

-

Photograph

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Roquefort c.1919–20 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, January 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www