Turner Bequest CCLXXIII

Sketchbook with marbled paper-covered boards and red leather spine and corners. Stamped in black ‘CCLXXIII’ at the top of the front cover and similarly on the back cover.

98 leaves of unwatermarked white wove paper from an unknown maker. Approximate page size: 116 x 186 mm.

Numbered ‘290’ as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the executors of the Turner Bequest on the inside front cover of the sketchbook. This page, which was not drawn or written on by Turner, carries the following inscriptions:

Inscribed in brown ink by Henry Trimmer ‘No 293 – | Contains 93 Leaves | Pencil Sketches on | both sides – [signed] H.S. Trimmer’ top

Signed in brown ink by Charles Turner ‘C Turner’ beneath Trimmer’s signature

Signed in pencil by John Prescott Knight ‘JPK’ to the bottom left of Charles Turner’s signature, and again to the right of Eastlake’s signature

Signed in pencil by Charles Lock Eastlake ‘C.L.E’ at the centre of the page

Blindstamped with the Turner Bequest stamp upper centre left

Inscribed in pencil ‘S95’ top left

Inscribed in pencil (perhaps by Knight) ‘83 leaves drawn on – only 87 in all’ centre

Stamped in black ‘CCLXXIII’ top

98 leaves of unwatermarked white wove paper from an unknown maker. Approximate page size: 116 x 186 mm.

Numbered ‘290’ as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the executors of the Turner Bequest on the inside front cover of the sketchbook. This page, which was not drawn or written on by Turner, carries the following inscriptions:

Inscribed in brown ink by Henry Trimmer ‘No 293 – | Contains 93 Leaves | Pencil Sketches on | both sides – [signed] H.S. Trimmer’ top

Signed in brown ink by Charles Turner ‘C Turner’ beneath Trimmer’s signature

Signed in pencil by John Prescott Knight ‘JPK’ to the bottom left of Charles Turner’s signature, and again to the right of Eastlake’s signature

Signed in pencil by Charles Lock Eastlake ‘C.L.E’ at the centre of the page

Blindstamped with the Turner Bequest stamp upper centre left

Inscribed in pencil ‘S95’ top left

Inscribed in pencil (perhaps by Knight) ‘83 leaves drawn on – only 87 in all’ centre

Stamped in black ‘CCLXXIII’ top

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

Exhibition history

References

The Staffa sketchbook is one of twelve books that Turner used during his 1831 tour of Scotland, undertaken to collect material to illustrate a new edition of Sir Walter Scott’s Poetical Works (see Tour of Scotland for Scott’s Poetical Works 1831 Tour Introduction). The maker of the sketchbook has not been determined, and Peter Bower, who studied the papers of the Turner Bequest, has been unable to determine the maker of this paper He points out that while the paper is similar to the wove paper made at the two Whatman paper mills in England, Turkey and Springfield, it could also have come from a Scottish source.1 Turner purchased several of the sketchbooks that he used on this tour in Scotland.

The title seems to derive from John Ruskin’s labelling of one of the three packets in which he distributed the leaves of the book after breaking it up: ‘293. Scotland (Staffa)’. Ruskin presumably recognised some of the sketches of Staffa, and A.J. Finberg, who named the book after this note, may have intended to point out the book’s connection to Turner’s oil painting Staffa, Fingal’s Cave exhibited 1832 (Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection).2

The sketchbook contains views of the west coast of Scotland within the vicinity of Oban, and sketches made during Turner’s steamboat journey to the island of Staffa, as well as views of Glencoe and the journey to Fort William. Turner’s visit to the west coast was made in connection to the Lord of the Isles volume of Sir Walter Scott’s Poetical Works, but seems also to have been a personal ambition. As he stated in a letter to Sir Walter Scott about three months before he set off: ‘when I get as far as Loch Kathrine [Katrine] shall not like to turn back without Staffa Mull and all. A steam boat is now established to the Western Isles so I have heard lately and therefore much of the difficulty becomes removed’.3 Having made his sketches he headed north towards Inverness and on to Evanton to visit his friend and patron, Hugh Munro at Novar House. There is an overlap with the Stirling and the West sketchbook (D26436–D26618; D41082–D41083 complete; Turner Bequest CCLXX), which Turner had half filled before opening the present book, and returned to for a while in preference to Staffa to record his journey to Skye.

Turner first opened the Staffa sketchbook towards what is now considered the back, in terms of folio order, on his approach to Loch Etive which he reached by land from Inveraray (folio 95 verso; D26929). The first significant subject, however, is Dunstaffnage Castle at the mouth of Loch Etive (folio 89; D26916). The artist made numerous studies of the ruins which came in useful when he was asked to paint a watercolour to be engraved as an illustration to Sir Walter Scott’s Prose Works: Dunstaffnage circa 1832–5 (Indianapolis Museum of Art).4

Turner gave equal attention to Dunollie Castle, which he either passed on his way to Oban or visited on a short excursion from the town. The clifftop ruin features in views of the town and the surrounding coast and in close-up studies, though Turner never worked any of these up into a formal composition (folio 95; D26928).

Oban was the artist’s temporary base on the west coast. A letter from Turner to Edward Francis Finden sent from Oban on 2 September 1831 gives us a date for Turner’s time in the town.5 While there he made a short series of sketches and studies depicting the busy harbour and recording passengers waiting for the steamboat at the pier (folio 58 verso; D26855). The artist also made a few sketches from around the town (folio 79 verso; D26897) and from the Gallanach Cliffs to the south (folio 60; D26858). From Gallanach (folio 79; D26896) Turner took a ferry to the island of Kerrera where he took a great interest in Gylen Castle. Even though he had not been commissioned to sketch the castle it proved to be a fascinating and fruitful subject. In a long series of sketches he recorded the ruin and its dramatic clifftop setting from every direction (folio 63 verso; D26865). Turner walked to Barr-nam-boc on the western side of Kerrera (folio 62 verso; D26863) where he could have caught the ferry to Mull, though he seems to have first returned to Oban.

He put away the Staffa sketchbook for a while as he set off for the Isle of Skye. Turner then embarked on a steamboat for Skye, opening the first of two small notebooks, Sound of Mull no.1 (D26936–D26948; D26950–D26954; D41019–D41020 complete; Turner Bequest CCLXXIV) which he soon finished before going on to the Sound of Mull no.2 sketchbook (D26955–D26965; D41021–D41022 complete; Turner Bequest CCLXXV), also filling this before he reached the island. He then opened the Stirling and the West sketchbook again, which he used during his time on Skye and on the journey from there to Tobermory on Mull.

At Tobermory the artist returned to the Staffa sketchbook, now starting again at the other end of the book. A series of sketches depict the waterfront and Tobermory Bay from above the rooftops of the village (folio 1 verso; D26749). From here he embarked on a day trip to Staffa and Iona on the Maid of Morven steamboat.6 Sketches record the boat’s passage to the mouth of the Sound of Mull (folio 43; D26823), and south towards Staffa, with the islands of Lunga and the Treshnish Islands (folio 42; D26821). Turner first glimpsed Staffa from the north and made various views of it as he approached, steamed around the western side and landed at the south-east (folio 40; D26817).

As he recorded in a letter to James Lenox fourteen years later, he and some of the other passengers landed and visited Fingal’s Cave. This was the main purpose of Turner’s visit. The cave had been made famous by Joseph Banks, whose geological description was published in Thomas Pennant’s popular A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides 1772, and by subsequent descriptions by Dr Samuel Johnson, James Boswell (who visited in 1773), and John Macculloch, who wrote about the cave in The Transactions of the Geological Society (no.II, 1814) and in his book, The Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland (1824). The naming of the cave after Fingal from the Ossian poems of James Macpherson brought Romantic associations, and was probably part of the inspiration for Walter Scott’s visits to the island in 1810 and 1814 which he drew upon for his poem The Lord of the Isles. Scott no doubt shared his experiences of the island with Turner. A note on the inside front cover of the Abbotsford sketchbook (Turner Bequest CCLXVII; Tate D40995) records that Turner had by now been commissioned to paint a view of Staffa to be engraved for the Lord of the Isles volume of Scott’s Poetical Works: Fingal’s Cave, Staffa circa 1833–4 (whereabouts unknown).7 Fingal’s Cave was presumably chosen as the most iconic and Romantic feature of the island. It was already familiar to many through prints such as William Daniell’s aquatint In Fingal’s Cave, Staffa (Tate T02796), published as part of his A Voyage Round Great Britain 1814–25. In fact, Turner seems to have based his composition on Daniell’s image more than on his own sketches (folio 29 verso; D26798).

The mouth of the cave is also shown in Turner’s oil painting of Staffa, Fingal’s Cave exhibited 1832 (Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection),8 which depicts the south-east corner of the island and a rough sea with a steamboat and squally clouds above. Turner’s account of his journey can be closely related to the painting, including the sunset which he described to Lenox: ‘The sun getting towards the horizon, burst through the rain-clouds’.9 According to the viewpoint of the picture we are in fact looking north-east, making a sunset impossible, though autobiographically and thematically a sunset is more likely than a sunrise, meaning that Turner took artistic licence with this painting. The viewpoint is not based directly on any sketch, and Turner may have again used a print by Daniell for the composition (see folio 24 verso; D26788). As he recalled in his letter, bad weather on the return journey forced the boat to seek shelter in what he called ‘Loch Ulver’, presumably referring to Loch na Keal (folio 41 verso; D26820); there was no time to visit Iona.

Presumably spending the night at Tobermory, Turner may have executed a further series of sketches (folio 1 verso; D26749) before returning via the Sound of Mull to Oban. Although he had already made sketches of the sound on the outward journey, he took the opportunity to sketch it again along with the castles of Aros, Ardtornish and Duart in a sequence across folios 48–57 verso (D26833–D26852).

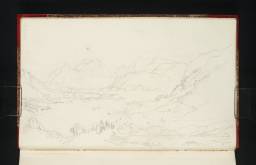

Turner continued his journey from here by steamboat, heading up the Lynn of Lorn and out into Loch Linnhe, passing Castle Stalker (folio 38 verso; D26814) on his way to Ballachulish (folio 2; D26750). Here he broke his journey to make a round trip to Glencoe. Despite not being on his list of subjects to collect for Scott, Turner obviously saw the potential in the dramatic landscape of the glen and its historic associations with the Glencoe Massacre of 1692. The visit proved useful when Turner was commissioned to paint Glencoe for an edition of Scott’s Prose Works: Glencoe circa 1833 (Rhode Island School of Design).10 The work is not based on any sketch in particular, despite Turner making a long series of beautifully executed views along the glen (see folio 2 for references).

Returning to Ballachulish Turner continued his journey north up Loch Linnhe to Fort William where he made his final sketches in the book (folio 8 verso; D26760). At Fort William he also opened the Fort Augustus sketchbook (D26966–D27045 complete; Turner Bequest CCLXXVI).

The sketches in the Staffa sketchbook are generally carefully executed with a high degree of topographical and architectural accuracy. Many use a full page with the book held in the landscape format, though sometimes two or more sketches are made on a page in this format. In some cases the book is turned in the portrait format for three or more small sketches. In most cases the sketches are carefully positioned within the page boundaries to create pleasing compositions. However, it is interesting to note that despite the potential of many of these, the painting of Staffa and the watercolours of Dunstaffnage, Fingal’s Cave and Glencoe are not based closely on any single sketches, but instead take details from different sketches to re-imagine the subjects.

While some sketches contain a wealth of details such as the crowds at Oban mentioned above, or the architecture of Gylen Castle (folio 73 verso; D26885), others, such as the Fingals’ Cave, are more impressionistic, providing an accurate general sense of a place and its appearance, but lacking clarity of detail. In this case Turner’s approach can be partially explained by the fact that he had limited time to make his studies, and the weather was bad, preventing him from sketching in comfort. Another explanation, however, may be that he deliberately adopted a style that allowed him to capture the character of the cave and his impressions of it. A series of rapidly drawn vertical lines and loops therefore represent the columnar structure of the basalt rock and capture its lonely, damp and forbidding character.

Together with the Stirling and the West book, the Staffa sketchbook is a detailed record of the landscape of the west coast and Western Isles of Scotland, capturing Turner’s experiences as a picturesque tourist, and standing as a tribute to his vision of the area.

Bower points out that the ‘sketchbook has been rebound, not necessarily in the right order.’11 Finberg, in his inventory, refers to the covers being broken off, and the leaves being ‘distributed mainly into three packets’, with twenty-nine chosen for mounting and two for framing. The packets were labelled: ‘293. Scotland’, ‘293. Scotland (Staffa). 29 chosen for mounting. 2 for framing’, and ‘293. Scotland. Inferior leaves.’12 This was the work of John Ruskin who first inscribed page numbers on each page in blue ink (and in red ink on folio 97), before breaking up the book and dividing the pages into packages according to quality, choosing what he considered to be the more interesting pages to be made available for study and exhibition, although there are no records of any of these pages being exhibited, and no traces (such as fading due to light exposure or marks left by mounts) that suggest they were exhibited. Finberg lists only the contents of the third package (‘Inferior leaves’) as folios 1, 3, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 16, 22–34, 41, 42, 43, 44, 63, 71, 84, 86 and 87.

The sketchbook has now been rebound. The red leather spine has obviously been rebuilt, partially with new leather, and the reattachment of the leaves can be seen at the page gutters. Although Henry Trimmer wrote on the inside front cover that there were ‘93 leaves’, this is contradicted elsewhere on the page with the pencil inscription: ‘83 pages drawn on – only 87 in all’. It is not clear who wrote this, though it may have been John Prescott Knight, as his signed initials appear for a second time beneath the inscription. Charles Lock Eastlake’s initials, however, are also written below the inscription. This suggests that at some time, either before or after Trimmer examined the sketchbook, six of the pages were missing. Ninety-seven had been found when John Ruskin numbered the pages in blue ink. Having completed his numbering Ruskin must have come across the ninety-eighth page as he inscribed this with red ink. That page has now been bound before the page inscribed ‘97’ meaning that the final two pages are out of sequence with the rest of the book. The folio numbers therefore match the Ruskin inscriptions and Finberg’s Turner Bequest numbers until folio 97, which is ‘CCLXXIII 98’ (D26934), and folio 98 which is ‘CCLXXIII 97’ (D26932).

As David Wallace-Hadrill and Janet Carolan have pointed out, the Maid of Morven usually operated between Glasgow and Inverness via the Crinan Canal, but the canal was closed during this period due to dry weather, so the boat was presumably put into service running day trips from Tobermory instead. Wallace-Hadrill and Carolan 1997, p.9.

How to cite

Thomas Ardill, ‘Staffa sketchbook 1831’, sketchbook, August 2010, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www