Henry Moore OM, CH Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Seated Woman: Thin Neck

1961

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961 marks a moment of transition in Henry Moore’s work, combining the artist’s established preoccupation with reclining and seated female figures – which dominated his work of the 1950s – with his burgeoning interest in thin, blade-like forms, which characterise some of his later more abstract sculptures.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Seated Woman: Thin Neck

1961

Bronze

172 x 814 x 1036 mm

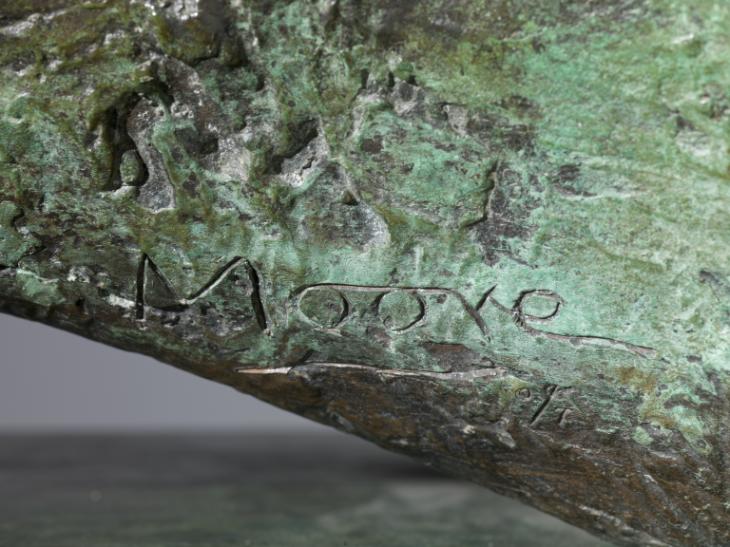

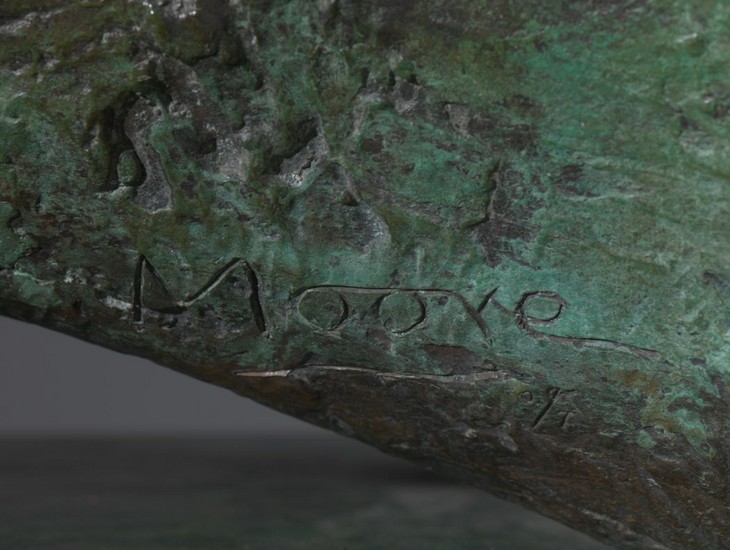

Inscribed by the artist ‘Moore’ under the figure’s left thigh

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 7

T02286

Seated Woman: Thin Neck

1961

Bronze

172 x 814 x 1036 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Moore’ under the figure’s left thigh

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 7

T02286

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1963

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston upon Hull, October–November 1963, no.38.

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, New Metropole Arts Centre, Folkestone, April–May 1966; City Art Gallery, Plymouth, June–July 1966, no.1.

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, 1969, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, August–October 1969, no.49.

1971

Henry Moore 1961–1971, Staatsgalerie Moderner Kunst, Munich, October–November 1971, no.1.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June 1978–August 1978, no number.

2004–5

Imaginary Landscapes, Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green, April–October 2004; Frederick Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park, Grand Rapids, Michigan, January–May 2005.

2010–11

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011, no.147.

References

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.243 (?another cast reproduced pl.233).

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, New Metropole Arts Centre, Folkestone 1966, reproduced.

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.278.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.358–9.

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, 1969, exhibition catalogue, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo 1969, reproduced.

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, pp.261–2 (?another cast reproduced pls.631–2).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, reproduced p.45.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, p.161 (full-size plaster reproduced pl.138).

1981

The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, reproduced pp.128–9.

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Sculpture 1955–64, 1966, revised edn, London 1986, no.472, p.46 (?another cast reproduced pls.106–7).

1987

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, pp.195–6 (full-size plaster reproduced p.196).

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced p.200.

2012

Henry Moore: Large Late Forms, exhibition catalogue, Gagosian Gallery, London 2012 (another cast reproduced pp.95–9).

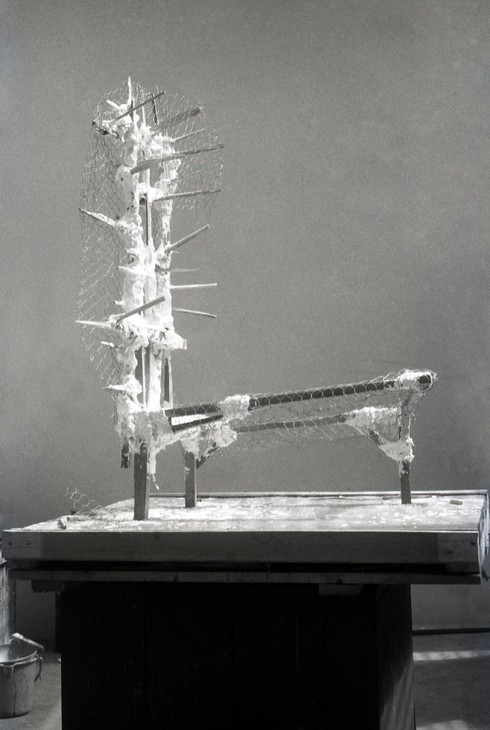

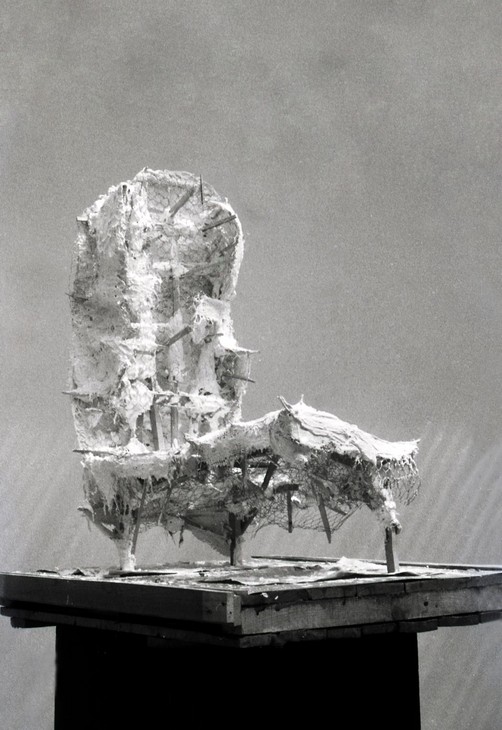

Technique and condition

This is a large bronze sculpture of a seated woman mounted on a rectangular bronze base. The bronze would have been cast from a mould taken from a plaster version of the sculpture, which Moore and his assistants made by building layers of plaster onto a supportive armature constructed from wood and wrapped in scrim (fig.1). The surface of the bronze replicates the surface of the plaster version, which was heavily textured by Moore. For example, it appears that a spatula was used to slather wet plaster across the sculpture (fig.2), while marks produced by files, surform blades and chisels indicate where Moore carved the plaster back after it had hardened. A number of deeply gouged striations can also be seen on the surface in certain areas.

Armature for Seated Woman: Thin Neck under construction in Moore's studio 1961

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Armature for Seated Woman: Thin Neck under construction in Moore's studio 1961

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Detail of surface texture of Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of surface texture of Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Soon after it was finished the plaster sculpture was sent to the Art Bronze Foundry in London to be cast in a bronze edition of seven plus one artist’s copy. It was common practice for foundries to cut plasters of this size into sections so that smaller, more straightforward moulds could be created of individual parts. This sculpture was cut into three sections, which were then cast separately and welded together. There are visible traces of white investment in some of the sculpture’s crevices, suggesting that the three sections were cast using the traditional lost wax process (fig.3). Residues of dark sand underneath the rectangular base indicate that this section was more likely to have been cast using the sand casting technique. Horizontal weld lines can be seen traversing the figure’s lower stomach and the back of its neck (fig.4). These weld lines were textured with small chisels and punches to integrate them with the surrounding surface.

Detail of casting investment in Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of casting investment in Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of welding seam on Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of welding seam on Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

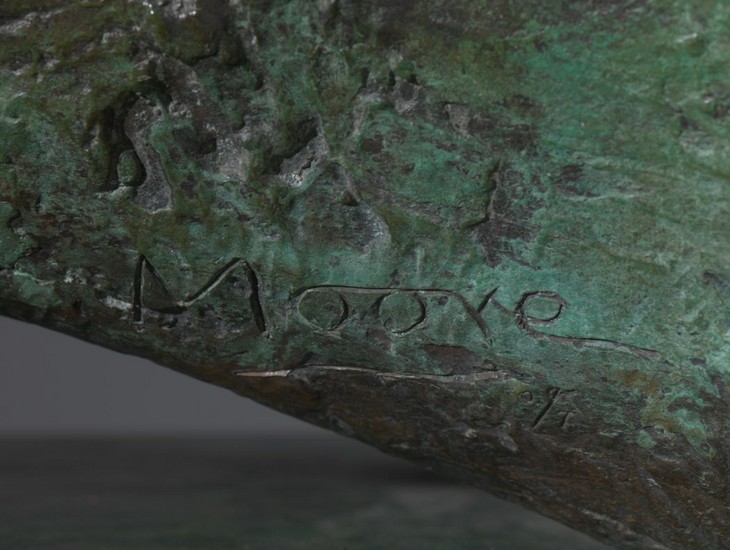

After it had been cast, assembled and cleaned the sculpture was patinated using a range of chemical solutions that reacted with the bronze to produce coloured compounds. The patina on this sculpture is formed of blue and yellowish greens, beneath which is a uniform layer of brown-black (fig.5). The darker layer was applied first, possibly using a potassium or ammonium polysulphide solution. It would have either been applied cold or with a low level of heat, which would have served to further darken the colour. Many different patina recipes can be used to produce green colours on bronze but they often contain mixtures of copper and ammonium salts. Successive layers of this solution, which appears to have been applied cold and stippled onto the surface with a brush, would have been left to dry and develop into the opaque green now visible. The yellowish green tinge may have been achieved by applying a small amount of ferric nitrate solution over the blue-green patina. The surface was then coated with clear wax to consolidate and protect the patina. This has helped to preserve its condition, although it has become slightly worn on the more exposed surfaces.

Detail of patina of Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of patina of Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The base is reinforced underneath by a grid of horizontal and vertical cross-members and fixed to the sculpture by three bolts threaded from underneath: two on either side of the figure’s buttocks and one where its leg makes contact with the base. Moore inscribed his signature under the figure’s left thigh followed by the stamped edition number ‘0/7’, indicating that this was originally the artist’s copy (fig.6).

Lyndsey Morgan

October 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', October 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, October 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961 is a bronze sculpture of a seated female figure, rendered schematically with no arms and truncated legs, mounted on a bronze base. The head takes the form of a triangular wedge attached to a long and exceptionally thin, blade-like neck, from which the work gets its title, and looks upwards and over the figure’s left shoulder (fig.1). The thin front plane of the face narrows from the crown to the chin, while the flat sides of the head are devoid of facial markings or features.

Detail of head and neck of Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of head and neck of Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of torso of Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of torso of Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The thinness of the neck is at odds with the figure’s large, bulky torso (fig.2). Two large boulder-like protrusions, which may be regarded as breasts, project from the flat rear surface and are separated by a concave recession in the position of the sternum. The abdomen below consists of shallower horizontal protrusion made up of craggy surfaces and sharp edges, underscored by a semi-circular groove that runs horizontally across the width of the torso. This hinge-like recess connects to the top of the thighs, which form an almost square-shaped plate with a hole at its centre (fig.3). The right thigh extends upwards on a diagonal and is suspended in mid-air, while the left knee, fused to the right, leads down to a short stump that connects to the base. The figure’s buttocks, separated by a curved arch, also rest on the base, while another shallow arch connects the left buttock and the left knee.

Detail of legs and buttocks of Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of legs and buttocks of Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961 (rear view)

T02286

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961 (rear view)

T02286

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Unlike the front of the sculpture the rear surface is relatively flat and uniform, resembling a thin shield-like form comparable to a tortoise shell (fig.4). This shell, which has a mottled, slightly uneven surface, is thinner around the edges and has an oval-shaped ridge that runs vertically down its centre, which gives the impression that the body is pressing against it from the other side.

From plaster to bronze

Seated Woman: Thin Neck originated from a small plaster maquette, probably made in 1960.1 During the late 1950s Moore had begun to make small plaster models or maquettes to develop his sculptural ideas. In 1978 he explained:

I have gradually changed from using preliminary drawings for my sculptures to working from the beginning in three-dimensions. That is, I first make a maquette for any idea I have for a sculpture. The maquette is only three or four inches in size, and I can hold it in my hand, turning it over to look at it from above, underneath, and in fact from any angle.2

It is likely that Moore made the plaster maquette for Seated Woman: Thin Neck in the small sculpture studio on the grounds of his home, Hoglands, in Perry Green, Hertfordshire. The studio also housed his ever growing collection of natural objects and according to the filmmaker John Read, Moore liked to ‘shut himself away here, rummaging around, pondering and exploring’ the shapes of bones, shells and flint stones.3 In 1963 Moore explained to the critic David Sylvester how he borrowed and reconfigured the shapes of these objects for his own designs:

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press them into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before.4

It is likely that the undulating torso of Seated Woman: Thin Neck was produced by pressing a stone or bone into clay and pouring plaster into the depression it left. This piece of plaster would have then become the basis of the small maquette. The thin rim and smooth face of the figure’s back is consistent with the shape that would have been formed by plaster spilling over the flat upper surface of the mould. Once these pieces of plaster had hardened Moore could then add or subtract forms, and smooth or sharpen edges and points as he wished.

Photograph of bronze cast of Maquette for Seated Woman: Thin Neck c.1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Photograph of bronze cast of Maquette for Seated Woman: Thin Neck c.1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

When I make a small maquette, it is rather like an architect making a sketch for a building on an envelope. In his mind it is a full-size building. In the same way, with my small plaster maquettes, I am thinking of something much larger. By looking at a maquette close to, I can relate it to some distant object and imagine it as huge. It’s all a question of mental scale and not physical size.7

The plaster maquette would have served as the template for the larger sculpture. The first stage in the scaling-up process involved taking detailed measurements of the small maquette, which were then multiplied according to the ratio of enlargement. An internal armature corresponding to these specifications was then constructed from lengths of wood joined together by scrim, a bandage like fabric soaked in wet plaster (fig.6). Each length of wood was precisely measured so that its end point corresponded with a ‘landmark’ or specific point on the surface of the sculpture.8 This enlargement process would have probably been carried out in the White Studio in the grounds of Hoglands by one or more of Moore’s sculpture assistants, who in 1961 included Clive Sheppard and Bill Smith. Moore was able to allocate the bulk of this work to his assistants because, as curator Julie Summers has noted, it was ‘a scientific rather than artistic process’.9 Successive layers of plaster were then built up over the armature and the sculpture began to gain mass and form. Moore would have taken over towards the end to texture the surface using an array of tools including chisels, files and sandpaper (fig.7). Cast directly from the plaster, the bronze retained these different textures.

Armature for Seated Woman: Thin Neck draped in scrim, 1961

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Armature for Seated Woman: Thin Neck draped in scrim, 1961

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Plaster

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Seated Woman: Thin Neck is not stamped with a foundry mark but records held at the Henry Moore Foundation confirm that it was cast at the Art Bronze Foundry in London in 1961. Traces of investment in the crevices of the sculpture suggest that it was cast using the lost wax method, which would have required the foundry to cut the plaster sculpture into sections and make moulds from each piece, into which the molten bronze could be poured. Once all of the individual bronze pieces were cast they were welded together, and the resulting seams filed down until they were virtually imperceptible.

The sculpture would then have been cleaned before a patina was applied. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the bronze surface. A dark base layer was probably applied to this sculpture first, followed by blue-green and then lighter green layers. There are several green drip marks on the upper thigh and buttock region of the figure and yellowish patches are visible in a number of areas (fig.8). Although the sculpture was coated in a layer of protective wax, the patina has dulled around the edges of the figure’s back.

Sources and development

Moore explained the origins of this work in an undated statement reproduced in Philip James’s 1966 book Henry Moore on Sculpture:

Since my student days I have liked the shape of bones, and have drawn them, studied them in the Natural History Museum, found them on sea-shores and saved them out of the stewpot ... There are many structural and sculptural principles to be learnt from bones, e.g. that in spite of their lightness they have great strength. Some bones, such as the breast bones of birds, have the lightweight fineness of a knife-blade. Finding such a bone led to me using this knife-edge thinness in 1961 in a sculpture Seated Woman (thin neck). In this figure the thin neck and head, by contrast with the width and bulk of the body, give more monumentality to the work.10

In that it follows from a series of reclining and seated women made in the late 1950s and precedes a sequence of sculptures based on the knife-edge form in the early 1960s, Seated Woman: Thin Neck may be regarded as a transitional work in which Moore’s figurative and abstract preoccupations were brought together.

A photograph taken by John Hedgecoe and published in 1968 shows the head and shoulders of Seated Woman: Thin Neck alongside those of another female figure sculpture, probably Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (Tate T06825).11 Commenting on this photograph in Hedgecoe’s book Moore asserted that ‘the contrast of these two heads shows that facial features are not essential for expression. With her long neck, one is distant and proud while the other is more sympathetic’.12 In the same publication Moore also stated that ‘in figurative sculpture, the head is, for me, the vital unit. It gives scale to the rest of the sculpture and, apart from its features, its poise on the neck has tremendous significance’.13 His use of the more dramatic and angular knife-edge form in place of an identifiable, if out-of-proportion, neck and head distinguishes this work from the female figures of the 1950s.

Henry Moore

Standing Figure Knife Edge 1961

Bronze

Yorkshire Sculpture Park

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Standing Figure Knife Edge 1961

Yorkshire Sculpture Park

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore

King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

A cast of Seated Woman: Thin Neck was exhibited at Marlborough Fine Art in London between July and August 1963. The catalogue for the exhibition described it as a solo display of new works by Moore, but the gallery space was in fact shared with paintings by Francis Bacon. Tate acquired Moore’s Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962 (Tate T00603) and Bacon’s Study for Portrait on Folding Bed 1963 (Tate T00604) from this exhibition.

The critical response to the two-person show was generally positive, with Nigel Gosling writing in the Observer that ‘any exhibition paring Henry Moore and Francis Bacon is sure to be a hit’.17 In addition to Seated Woman: Thin Neck, recent works on display included casts of Three Piece Reclining Figure No.1 1961–2 (Tate T02289) and Locking Piece 1963–4 (Tate T02293). Writing in the Times the critic David Thompson asserted that ‘Moore has never looked grander, more inventive, more the absolute master of his means of expression’.18 Similarly, Gosling reflected that ‘at 65, Moore might be expected to be slowing down in invention, but here he seems to be as fertile as ever. He not only solves problems – we all know he can do that. He finds fascinating problems to solve’.19 Gosling identified Seated Woman: Thin Neck as a ‘perfectly finished piece ... Her back is a shield, her head an axe, her lap is a blow-hole in the rock. She twists and yet sits firm; she has no explicit breasts or arms or legs but makes you feel they are somewhere around’.20 In a review for the Listener the curator Bryan Robertson identified the shift that had occurred between Moore’s sculptures of female figures in the 1950s and the works on show at Marlborough Fine Art, reserving special praise for the power of the later works:

The new sculpture of Henry Moore confirms a feeling that after marking time for a while in the nineteen-fifties he has moved through to an intensity of feeling and constructive energy which has demanded and found a considerable extension of sculptural language. The knife-edge forms, the three-piece reclining figure ... the locking piece and the knife-edge two-piece confrontation are all brilliant and forceful inventions. The essence of Moore’s work is always to be found in his grimmest or most ferocious sculpture; his matronly figures and other sweeter preoccupations lack the conviction and the formal power of his darker side.21

The Henry Moore Gift

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961

Tate T02286

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Seated Woman: Thin Neck was cast in an edition of seven plus one artist’s cast. Tate’s version is stamped with the edition number ‘0/7’, indicating that this was the artist’s copy (fig.11). The full-size original plaster is held in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Other bronze casts are held in the collections of the Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green; Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, Toyota; Des Moines Arts Centre, Des Moines; and the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle. The remaining casts are believed to be in private collections.

Alice Correia

October 2013

Notes

John Read in Henry Moore: One Yorkshireman Looks at His World, dir. by John Read, television programme, broadcast BBC 2, 11 November 1967, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8807.shtml , accessed 3 November 2013.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, broadcast BBC Radio, 14 July 1963, p.18, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, p.46.

Elizabeth Brown, ‘Moore Looking: Photography and the Presentation of Sculpture’, in Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, p.290.

See Richard Wentworth, ‘The Going Concern: Working For Moore’, Burlington Magazine, vol.130, no.1029, December 1988, p.928.

Julie Summers, ‘Fragment of Maquette for King and Queen’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.126.

Henry Moore cited in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture: A Collection of the Sculptor’s Writings and Spoken Words, London 1966, p.278.

Related essays

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Erich Neumann on Henry Moore: Public Sculpture and the Collective Unconscious Tim Martin

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Seated Woman: Thin Neck 1961 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, October 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www