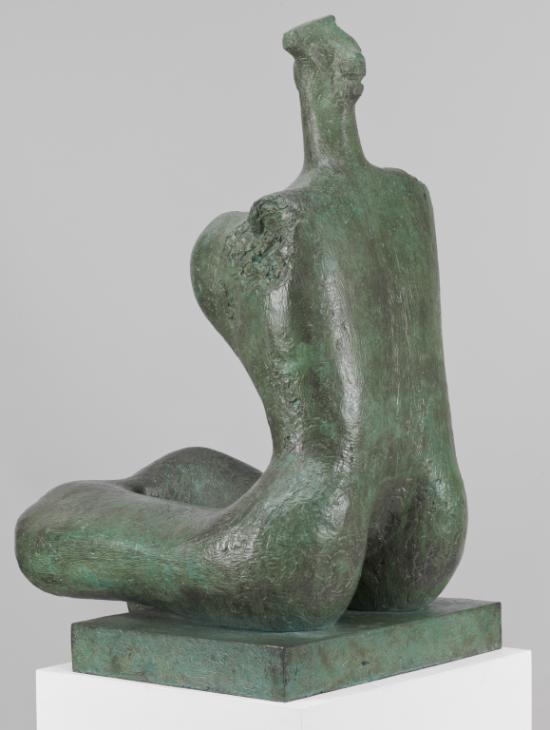

Henry Moore OM, CH Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown

Image 1 of 13

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Woman

1957-8, cast date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Woman 1957–8 is one of the largest in a series of sculptures of female figures made by Moore during the 1950s. With reference to Moore’s early and enduring interest in Palaeolithic sculpture, this work has been interpreted as a modern-day fertility goddess, but it is most notable for having no arms and truncated legs.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Woman

1957–8, cast date unknown

Bronze

1441 x 791 x 921 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore’ on top of base.

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 8

T02280

Woman

1957–8, cast date unknown

Bronze

1441 x 791 x 921 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore’ on top of base.

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 8

T02280

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1960–1

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, Whitechapel Gallery, London, November 1960–January 1961, (?another cast exhibited no.56).

1961

Henry Moore, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, July–September 1961 (?another cast exhibited no.42).

1961

Henry Moore, Musée Rodin, Paris, March–April 1961, (?another cast exhibited no.41).

1965

Henry Moore, Museu de Arte Moderna, Rio de Janeiro, January–February 1965, (?another cast exhibited no.19).

1966

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Salla Dalles, Bucharest, February–March 1966; Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava, April–May 1966; National Gallery, Prague, June 1966; Israel Museum, Jerusalem, September–October 1966; Tel-Aviv Museum, Tel-Aviv, November–December 1966, no.23.

1967

Henry Moore, Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield, July–September 1967, no.3.

1968

Henry Moore, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, May–July 1968; Museum Boymans-Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, September–November 1968, no.95.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978, no.5.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1983

Henry Moore: Winchester 1983, Winchester Castle, Winchester, July–September 1983, no number.

2013–14

Bacon / Moore: Flesh and Bone, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, September 2013–January 2014, no.35.

References

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, pp.230–1, reproduced pls.181–2.

1962

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, M. Knoedler and Co., New York 1962 (?another cast reproduced pp.26–7).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of His Life and Work, London 1965, p.221, reproduced pl.204.

1966

Donald Hall, Henry Moore: The Life and Work of a Great Sculptor, London 1966 (?another cast reproduced p.145).

1967

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1967, reproduced.

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.127, reproduced p.121.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, p.326 (?another cast reproduced pp.322–4).

1971

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture: A Collection of the Sculptor’s Writings and Spoken Words, New York 1971, p.281.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence 1972, reproduced p.171.

1976

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1976 (?another cast reproduced p.478).

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977, p.8.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Cartwright Hall, Bradford 1978, reproduced.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.38.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, pp.157–8 (original plaster reproduced pl.131, another cast reproduced pl.132).

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, exhibition catalogue, Palacio de Velázquez, Madrid 1981, reproduced pp.304–5.

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore: Volume 3: Complete Sculpture 1955–64, 1965, 2nd edn, London 1986, p.36 (another cast reproduced pls.71–3).

1987

Alan Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.183 (another cast reproduced no.132).

2013

Richard Calvocoressi, Martin Harrison and Francis Warner, Bacon / Moore: Flesh and Bone, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 2013, reproduced p.97.

Technique and condition

This is a large bronze sculpture of a seated woman mounted on a rectangular bronze base. The figure does not possess any arms and her legs appear to be truncated at the knee. Both the figure and the base are patinated a deep, vivid green.

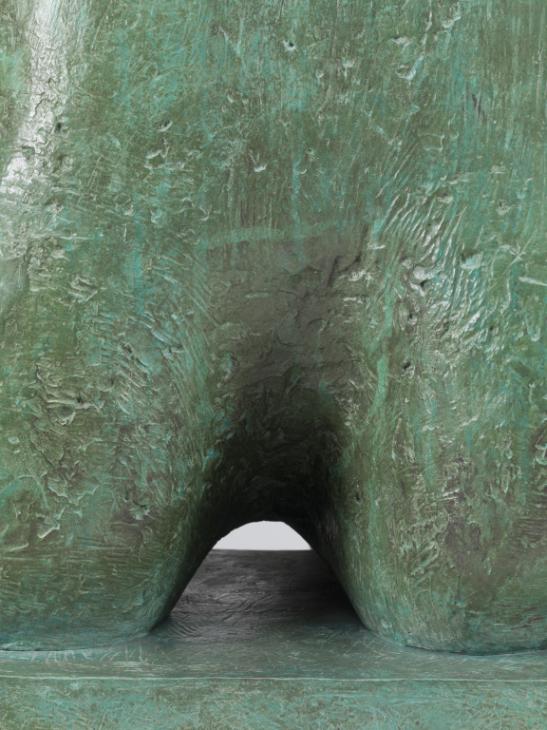

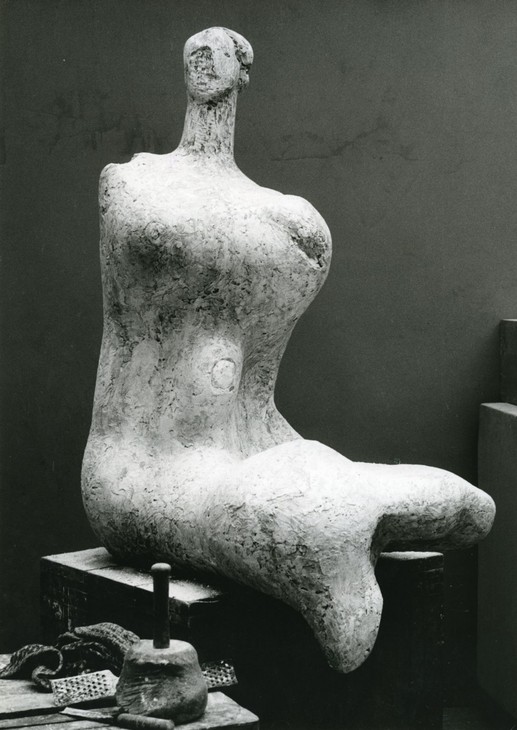

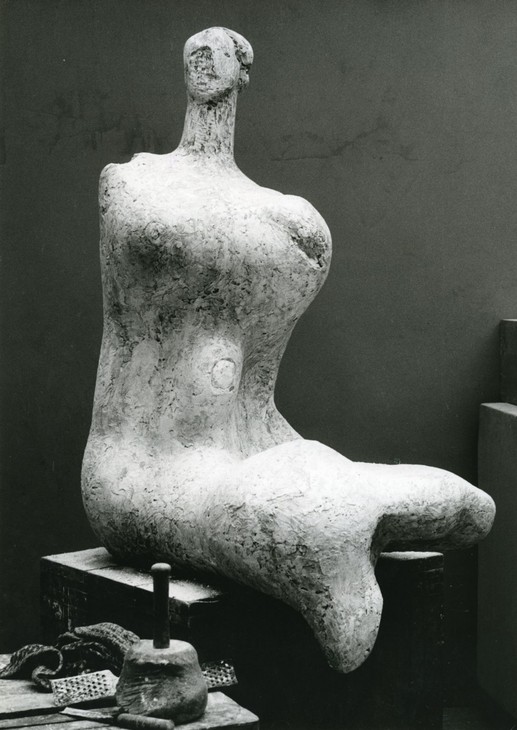

The bronze would have been cast from a mould taken from an original plaster version of the sculpture (fig.1). A plaster of this size would have been built up over an internal armature constructed most likely from lengths of wood and chicken wire draped with scrim. Wet plaster would have been applied to this structure, gradually building up the form of the figure, which, once completed, would have been textured by Moore using a range of tools and techniques. Areas on the surface of the bronze show how Moore used a spatula to apply the wet plaster, while striated marks would have been made once the plaster had hardened by cutting into the surface with surform blades and gouges. Moore sometimes created different textures to distinguish certain forms and areas of the sculpture. For example, in the arm sockets the plaster has been left rough and deeply pitted, whereas the surrounding surfaces of the body are smoother and delicately striated (fig.2).

Full-size plaster version of Woman in Moore's studio c.1957–8

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Full-size plaster version of Woman in Moore's studio c.1957–8

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of arm socket of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of arm socket of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Once it was finished the plaster was sent to the Noack Foundry in West Berlin to be cast in bronze. It was common practice for the foundry to cut plasters of this size into sections so that smaller, more straightforward moulds could be created. Casting a sculpture in sections also allowed the foundry to use a smaller crucible, which made the pouring of molten bronze into the moulds easier to control, and reduced the risk of faults and imperfections in the resulting casts. Residual traces of casting investment are visible in crevices in the bronze, suggesting that the sculpture was cast using the traditional lost wax process (fig.3).

Detail of casting investment on Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of casting investment on Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of filed weld seam on Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.4

Detail of filed weld seam on Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

After they were cast the individual sections would have been welded together to form the sculpture. Any weld lines would be carefully filed down and textured with punches to integrate them with the surrounding surface. This process is called ‘chasing’ and is also used to disguise repairs to the bronze, such as the square outline in the cleft of the buttocks (fig.4). The base was cast separately and fixed to the sculpture using bolts attached from the underside. Although it has not been possible to examine the underside of the base, the inspection of bases of similar sculptures by Moore has shown them to have been sand cast. Before the sculpture left the foundry it would have been cleaned, but otherwise there are no signs of any other post-cast finishing and the original marks that Moore made in the plaster have been faithfully reproduced in the bronze.

Freshly cast bronze is usually coloured by means of a process called artificial patination. This involves the application of chemical solutions to the surface, which react with the bronze to produce coloured compounds. This sculpture has a vivid green patina variegated with shades of brown. Patinas are often made up of a number of different layers, and in this case it is likely that the brown colour was initially applied to the bronze, possibly using a chemical like potassium polysulphide, before a green layer was applied over it. Many different patina recipes can be used to produce green colours on bronze, but they often contain mixtures of copper and ammonium salts. The quality of this patina suggests that the solution was applied cold and stippled onto the surface with a brush. Successive applications would have been left to dry so that they eventually developed a dense green colour. The surface was then given a coat of protective wax, which is often used to build more colour onto the surface and in this case was probably tinted brown.

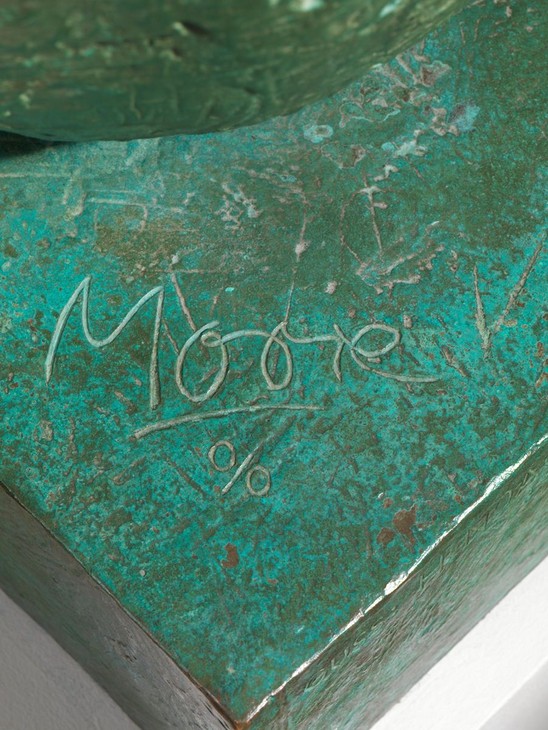

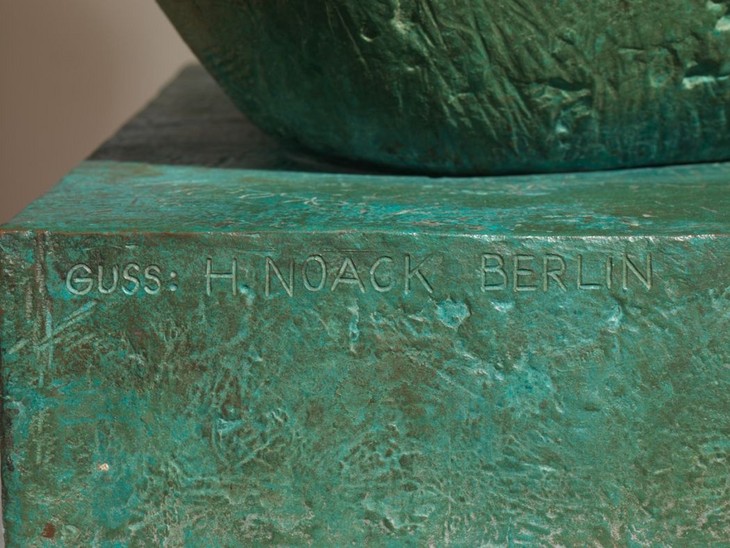

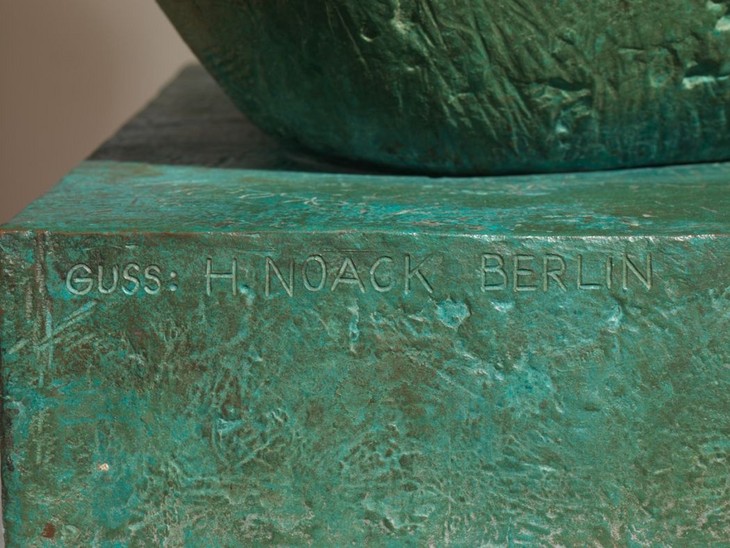

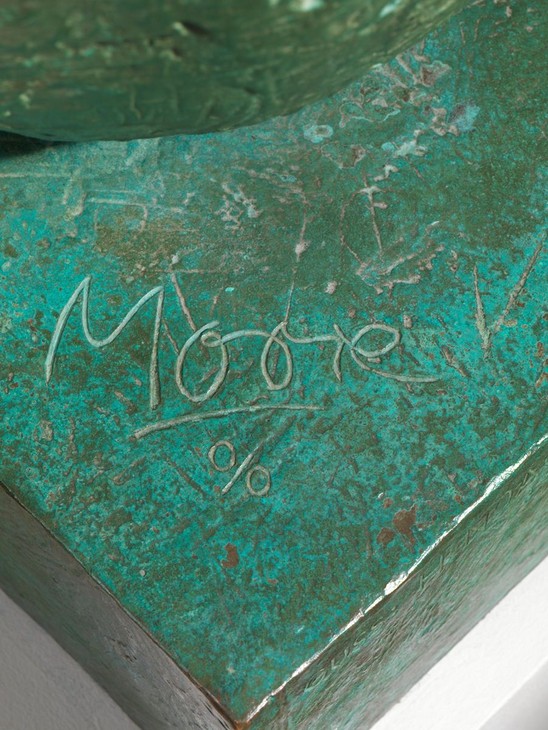

The sculpture is generally in good condition, although the edges of the base and the knees of the figure are a darker brown than the rest of the sculpture. This suggests that the green patina has been worn away in these areas by repeated handling. The artist’s signature ‘Moore’ has been inscribed into the top of the base along with the edition number ‘0/0’ (fig.5), indicating that this was the artist’s copy. The foundry mark ‘GUSS: H.NOACK.BERLIN’ has been stamped on one side of the base, immediately underneath the signature (fig.6).

Detail of artist's signature on Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of artist's signature on Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Lyndsey Morgan

January 2014

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', January 2014, in Alice Correia, ‘Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Woman 1957–8 is one of the last in a series of bronze sculptures of seated women that Henry Moore made in the 1950s. This naked figure, presented sitting upright on a plinth, has a large, bulbous torso and a disproportionately small head, but what is most striking is that it has no arms, while its legs resemble stumps and appear to have been truncated at the knees.

The figure’s elliptical head is turned to the right and is roughly the same height and width as the neck, which from certain angles appears to be pulled back, slightly lifting the chin (fig.1). A long, prismatic nose runs down the middle of the face, on either side of which eyes of different shapes and sizes have been defined. A single incision or scar runs parallel to the left-hand edge of the nose and a concave depression appears on the right side of the forehead. As with many of Moore’s female figures, Woman has a distinct mass of hair comprising two buns at the rear and a rounded oblong extending diagonally across the left side of the head.

The upper half of the torso is almost wholly formed by two enormous breasts, while the lower half is defined by a prominent central ridge (fig.2). The left breast is larger than the right and both project further than the ridge below. Circular incisions have been made on the breasts and ridge to signify nipples and the navel respectively. The mass of the rounded belly is emphasised by the concave sweep of the left hip and the torso as a whole is twisted slightly so that the broad, flat shoulders are oriented to the right. The shoulder sockets on either side of the torso are heavily textured with gouges. In contrast, the surrounding surfaces are more lightly textured, which gives the impression that the figure once had arms and that they were forcibly amputated (fig.3).

Detail of breasts and belly of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of breasts and belly of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of arm socket of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of arm socket of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The figure’s thighs extend from the hips at right angles to the torso and form an arched canopy over a tunnelled space beneath. Although they are joined at the knees, two thighs can be distinguished due to a hole in the sculpture’s lap. While the left thigh projects horizontally beyond the edge of the base and terminates in a rounded edge just above the knee, the right thigh is thinner at the hip but expands into a bulbous, bent knee, while a short stump extends downwards, perhaps denoting a calf (fig.4). The legs have rounded ends which, unlike the ragged shoulder sockets, suggest that they are the result of a natural deformation.

Henry Moore

Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The rear side is flat, with no protrusions or undulations apart from two rounded buttocks, which are flattened where they meet the base (fig.5). The left hip and buttock are slightly raised and push out to the side. An arched space between the buttocks makes it possible to see through the sculpture to the other side.

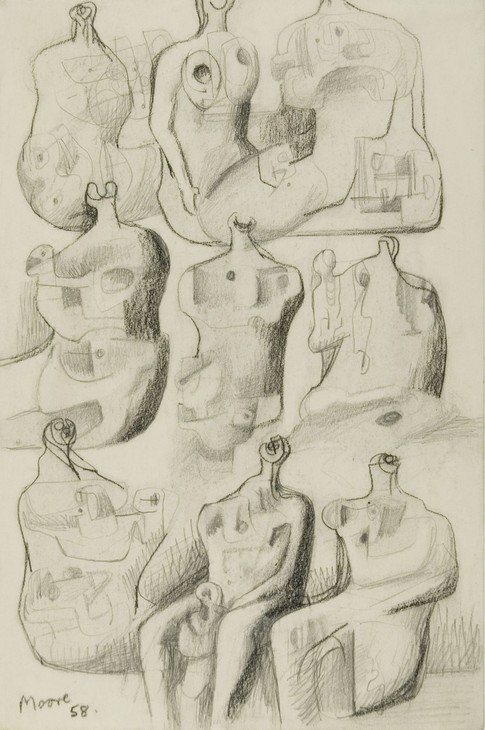

From plaster to bronze

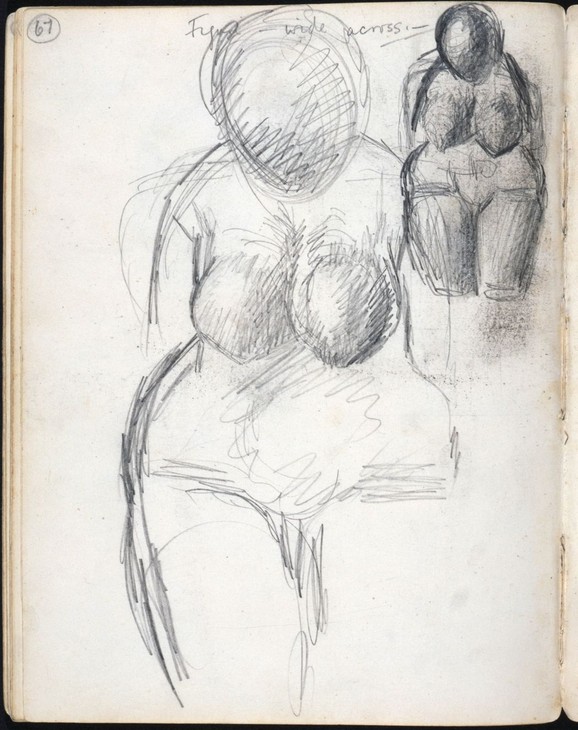

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Three Seated Figures c.1938, c.1956

Graphite and pastel on paper

278 x 185 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Three Seated Figures c.1938, c.1956

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore made the plaster maquette for Woman in 1956, most likely in the small studio in the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. Formerly the village shop, the building was used by Moore in the 1950s and 1960s as a private space in which to test out his ideas in three dimensions. Having created his maquette, Moore would have then used it as the template for his large-scale sculpture, which was begun the following year. By systematically charting and measuring specific points on its surface using grids and set-squares, it was possible to enlarge the maquette in plaster while retaining its original proportions. This process was probably carried out in the White Studio at Hoglands or, weather permitting, on the studio terrace. Much of the preliminary enlargement work would have been undertaken by one or more of Moore’s sculpture assistants, who in 1957 included Geoffrey Harris, Daryll Hill, Maurice Lowe and Stephen Rich.

Full-size plaster version of Woman in Moore's studio c.1957–8

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Full-size plaster version of Woman in Moore's studio c.1957–8

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of surface texture of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Detail of surface texture of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Once the full-size plaster version was complete it was sent to a professional foundry to be cast in bronze. Tate’s version of Woman was cast at the Noack Foundry in West Berlin, the name of which is stamped on the edge of the base (fig.9). During the 1950s and early 1960s Moore used a number of different foundries in London and Paris, but started working with Noack in 1958 following an introduction by the art dealer Harry Fischer of Marlborough Fine Art, London.3 The first and second casts of Woman were produced at the Art Bronze Foundry in London, but after being introduced to Noack Moore decided to complete the edition at the Berlin foundry. In 1967 Moore stated, ‘I use the Noack foundry for casting most of my work because in my opinion, Noack is the best bronze founder I know ... Also, the Noack foundry is reliable in all ways – in keeping to dates of delivery – and in sustaining the quality of their work’.4 Traces of casting investment can be detected on the bronze surface suggesting that it was cast using the lost wax technique.5

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Bronze

object: 1441 x 791 x 921 mm

Tate T02280

Presented by the artist 1978

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore OM, CH

Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Sources and development

Henry Moore

Seated Woman 1957

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Seated Woman 1957

L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

On long-term loan to Tate L01444

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From 1956 to 1958 he modelled two large sculptures called Seated Woman and Woman. The first woman is exaggerated in her womanly pregnancy, but complete with arms, hands and head. When Moore finished it, he was dissatisfied; it was too anecdotal, it dispersed its power. He made the second all torso, with enormous female rhythms of breast and womb and buttocks, and no head or arms. Here are the power and the feeling.8

Discussing Woman in 1968, Moore himself stated:

right from the beginning I have been more interested in the female form than in the male. Nearly all my drawings and virtually all my sculptures are based on the female form. ‘Woman’ has that startling fullness of the stomach and the breasts. The smallness of the head is necessary to emphasise the massiveness of the body. If the head had been any larger it would have ruined the whole idea of the sculpture. Instead the face and particularly the neck are more like a hard column than a soft goitred female neck.

‘Woman’ and ‘Seated Woman’ ... both have the big form that I like my women to have. ‘Woman’ emphasises fertility like the Palaeolithic Venuses in which the roundness and fullness of form is exaggerated.9

In 1926 Moore made a series of sketches of a small Palaeolithic sculpture, then known as the Venus of Grimaldi and subsequently called the Venus of Menton (fig.12). In these drawings, such as Study after ‘Venus of Grimaldi’ 1926 (fig.13), Moore appears to have devoted significant attention to reproducing the exaggerated size and roundness of the figure’s breasts and hips. Moore’s sketches were based on a reproduction of the ancient sculpture in the scholar Herbert Kuhn’s book Die Kunst der Primitiven (1923), which Moore is known to have consulted.10 Echoing Moore’s acknowledgement of the influence of the Palaeolithic Venus, in 1987 the curator Alan Wilkinson stated that ‘Woman is a mid-twentieth-century descendent of some of the earliest works of art in the world, the prehistoric sculptures of fertility goddesses’.11 He went on to identify Moore’s sculpture as ‘one of the most potent images of fertility produced in the twentieth century’.12

Female figure ('Venus of Grimaldi' or 'Venus of Menton') c.20,000 BC

Yellow steatite

470 x 20 x 120 mm

Musée d'Archéologie nationale et Domaine national de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Fig.12

Female figure ('Venus of Grimaldi' or 'Venus of Menton') c.20,000 BC

Musée d'Archéologie nationale et Domaine national de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Henry Moore

Study after Venus of Grimaldi 1926

Graphite on paper

222 x 172 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Study after Venus of Grimaldi 1926

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s interest in the Venus of Grimaldi can be contextualised with reference to a broad tendency in early twentieth-century European modern art known as ‘primitivism’. Primitivism is a term used by art historians to describe modern art that sought to emulate the forms and values of non-Western or ancient art, which were deemed to be more emotionally or spiritually authentic than the classicism of the European fine art tradition. Moore’s interest in non-Western and ancient cultures dates from 1920, when he read Roger Fry’s influential book Vision and Design (1920) while he was a student at Leeds School of Art. Fry was a respected art critic and Vision and Design included chapters on African, Islamic and ancient American art. He proposed that the aesthetic experiences generated by non-Western art possessed an authenticity and directness that academic European art, with its focus on anatomical accuracy and technical virtuosity, had lost.

In 1959 the German psychologist Erich Neumann aligned Moore’s later sculptures of rotund women with the artistic trope of the fertility goddess. He argued that ‘the achetype of the Great Mother around which Moore’s work revolves has not only been an object of veneration all over the world since the remotest times but was always, for that very reason, a subject for artistic representation as well’.13 Neumann defined the ‘Great Mother’ as the symbolic core of ancient societies, providing ‘nourishment, shelter and security’ and presiding as ‘the mistress of life and fertility’.14 He argued that ‘the sovereign power of motherhood determined the earliest phase of man’s development, and only later, with the growth of consciousness, was it superseded and overlaid by the significance of the father and the patriarchal values connected with the father archetype’.15 Neumann suggested that Moore’s attempt to readdress the ‘Great Mother’ archetype provided evidence that ‘a new shift of values is beginning, and with the gradual decay of the patriarchal canon we can discern a new emergence of the matriarchal world in the consciousness of Western man’.16 However, in 1977 the curator Alan Bowness offered a contrasting view to these generalised accounts of the nourishment and security offered by Moore’s large women. Specifically discussing Woman, Bowness suggested that the base upon which the figure sits intentionally creates a distance between the viewer and the figure. He concluded that Moore’s figure was ‘close to being drained of humanity ... almost too impersonal and withdrawn’.17

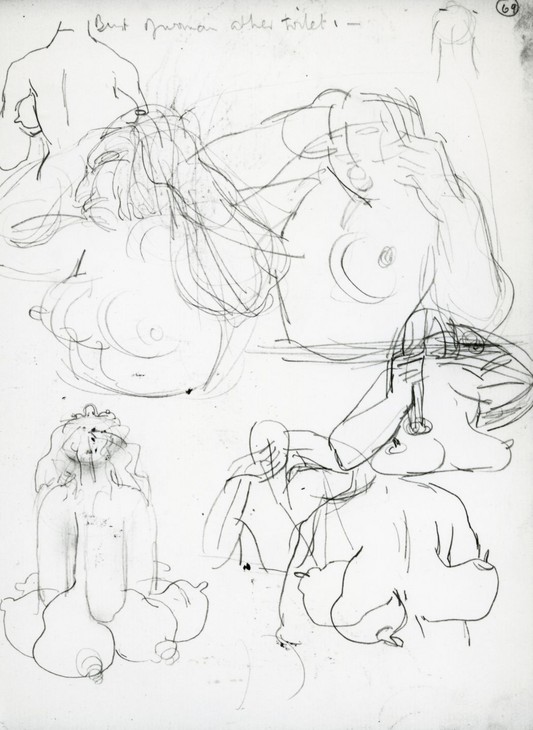

Henry Moore

Studies on the Theme of Bust of a Woman at Her Toilet 1925

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Studies on the Theme of Bust of a Woman at Her Toilet 1925

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

as the sketches developed, as curves and circles coalesced to form increasingly improbable organs, Moore’s imagination turned to the breast, as fullness and deformation; as fruit; as the servant of vision rather than nature, in its utter availability to the gaze: in the top left vignette a whole breast is improbably visible from behind its owner’s back. All these notions reach an impossible climax, so to speak, in the uncanny breast-as-column at lower left.19

Although Moore was generally reticent about the erotic undertones of his work, in 1974 he stated that ‘our own bodies are the basis of our understanding of the three-dimensional world. Everybody’s appreciation of form is also based on the appreciation of sex’.20 He elaborated upon this topic in 1983, saying:

As I do my work I am not conscious of erotic elements in it, and I have never set out to create an erotic work of art. My work is mainly intuitive. But of course it is true that almost any sculptured form can be seen as erotic and can arouse erotic associations in the minds of the viewer ... I have no objection to people interpreting my forms and sculptures erotically, relating my figures to erotic imagery in their own thinking. Part of the excitement of sculpture is the associations it can arouse, quite independent of the original aims and ideas of the sculptor. But I do not have any desire to rationalise the eroticism in my work, to think about consciously what Freudian or Jungian symbols may lie behind what I create.21

In 1960 the critic Will Grohmann identified two kinds of seated figure in Moore’s work. The first, he argued, conveyed repose and contemplation, while the second expressed ‘the moment before rising, jumping up, going into action’.22 Grohmann suggested that ‘the relaxed figures tend towards the classical, and the tense ones toward the demonic’.23 According to Grohmann, Woman can be regarded as ‘demonic’ in that, ‘the demonic figures ... are continuations of the destroyed and destroying themes that followed the end of the 1930s and the beginning of the 1950s, except that this time the conception is not based on hollow forms and an open framework, but on fully three-dimensional shapes that have been subjected to distortions that exercise a shock effect’.24

Early in its history Woman was variously known as ‘Torso’, ‘Seated Torso’ and ‘Parze’, with the version held in the Israel Museum still exhibited under the title Woman (Seated Torso, Parze). ‘Parze’ is the German word for ‘Fates’ and Grohmann, possibly prompted by this title, noted that he was tempted to call the sculpture ‘Fate’ but observed that:

Fate not in the sense of the Battersea Park figures [see Tate L01768], but in the sense of the Roman goddess of birth, who retained her connexion with the powers of destiny. She is mutilated like the Warrior, but less wilfully and hence has ‘remained’ a torso rather then ‘become’ one. The arms are missing and the legs stop at the knee, the chest is arched excessively far forward, the trunk swells out at the level of the inscribed navel, and the head sits small and timid on the tall neck, arousing a feeling of timidity in the observer. The whole composition is imbued with an aura of the superhuman and mysterious and is one of Moore’s masterpieces.25

While Moore’s Warrior with Shield 1953–4 (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery) presents the body of a mutilated figure, in Grohmann’s interpretation the absence of limbs in Woman does not indicate bodily trauma. Rather, he suggested that the body of Woman is offered as a complete, unified form and thus a powerful alternative physical reality.

The Henry Moore Gift

Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown, installed outside Cartwright Hall, Bradford, during Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, April–June 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.15

Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown, installed outside Cartwright Hall, Bradford, during Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, April–June 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

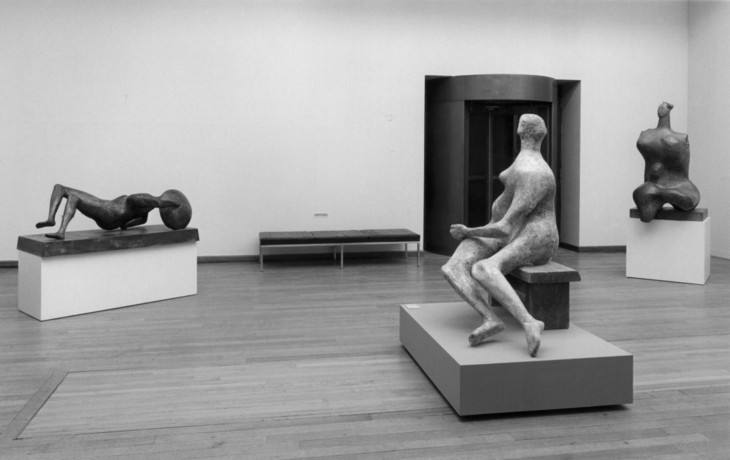

Woman was transported directly from Cartwright Hall to the Tate Gallery, where it was displayed in a major exhibition alongside the other thirty-five sculptures constituting the Henry Moore Gift. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.26 Woman was exhibited in gallery fifty-two alongside Falling Warrior 1956–7 (Tate T02278) and Seated Woman 1957 (Tate T02279; fig.16). The exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.27 At the close of the exhibition in late August 1978 the Director of Tate Norman Reid reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.28

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.16

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of artist's signature on Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Detail of artist's signature on Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown

Tate T02280

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Woman was cast in an edition of eight plus one artist’s cast. Tate’s version is stamped with the artist’s signature and the edition number ‘0/0’, indicating that it was originally the artist’s copy (fig.17). Other casts are held in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs; Clos Pegase Winery, Napa Valley; Portland Art Museum, Portland; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Montreal; and the British Council, London. Another bronze cast is housed with the original plaster in the Moore Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Alice Correia

December 2013

Notes

For a video explaining the lost wax process see http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/s/sculpture-techniques/ , accessed 16 January 2014.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, broadcast BBC Radio, 14 July 1963, p.4, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.183.

Henry Moore cited in Peter Webb, The Erotic Arts, London 1983, pp.378–9, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.115.

Related essays

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Erich Neumann on Henry Moore: Public Sculpture and the Collective Unconscious Tim Martin

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www