Henry Moore OM, CH Seated Woman 1957

Image 1 of 12

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Seated Woman 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Seated Woman

1957

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Seated Woman is part of a series of large sculptures of women made by Moore in the 1950s. The monumental, simplified forms of the woman’s body are indicative of the influence of Paul Cézanne on Moore’s work, while the figure’s misshapen belly was regarded by the artist as a sign of pregnancy.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Seated Woman

1957

Plaster on a wood bench

1488 x 1394 x 914 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

T02279

Seated Woman

1957

Plaster on a wood bench

1488 x 1394 x 914 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

T02279

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

2010

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010, no.141.

References

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, 1960, p.230 (bronze cast reproduced pls.179–80).

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1960 (bronze cast reproduced).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965 (bronze cast reproduced pl.208).

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.131 (bronze cast reproduced pls.43–4).

1966

Donald Hall, Henry Moore: The Life and Work of a Great Sculptor, London 1966 (bronze cast reproduced p.145).

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.127 (bronze cast reproduced p.119).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.326, 329 (bronze cast reproduced pp.327–8).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced pp.36–7.

2010

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced p.197.

Technique and condition

This larger than life-size plaster sculpture presents a nude female figure seated on a wooden bench. Moore made this plaster so that a mould could be taken from it, which was then used to cast the sculpture in bronze.

To make a plaster of this size Moore would have first had to construct a supportive internal armature that was probably made from metal and wood. Placing a magnet over certain areas of the sculpture indicates that the armature is partially made of steel. Moore applied successive layers of wet plaster over this structure, gradually building up the form before texturing the surface with deep gouges and striations that serve to emphasise the contours (fig.1).

Detail of surface texture of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of surface texture of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of right hand of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of right hand of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The figure sits upon a roughly constructed, unvarnished wooden bench designed so that the right hand would be placed directly on its upper face. This hand is now slightly raised as a result of the figure being wedged up underneath its right thigh (fig.2). There is no record of this treatment in the conservation files, and it may therefore have been carried out at Moore’s studio prior to Tate’s acquisition of the sculpture in 1978. It was probably an attempt to lessen the stress on the figure’s ankles, which have cracked slightly due to the weight they were originally required to support (fig.3). The conservation report for this sculpture notes that it has also sustained a number of small losses and received repairs.

Detail of cracks around the ankle of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of cracks around the ankle of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of head and neck of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of head and neck of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

To cast a large sculpture in bronze the full-size plaster is often cut into sections so that a number of smaller, less complex moulds can be made. A repair to the neck of the plaster figure suggests that the head may have been removed for this purpose, and then reattached to the body after the moulds had been made (fig.4). Similar repairs can be seen at the top of the thigh, as well as on the upper arm and ankles.

A fine brown wash has been applied to the surface of the sculpture, which serves to tone the whiteness of the plaster and highlight its texture. This wash was likely applied directly after the casting process to distinguish it as a unique, finished sculpture, rather than simply as a preliminary stage in the development of a bronze.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Seated Woman 1957 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Henry Moore’s Seated Woman 1957 is a larger than life-size plaster sculpture of a female figure seated on a wooden bench. This work was later used to cast the sculpture in bronze in an edition of six plus one artist’s copy.

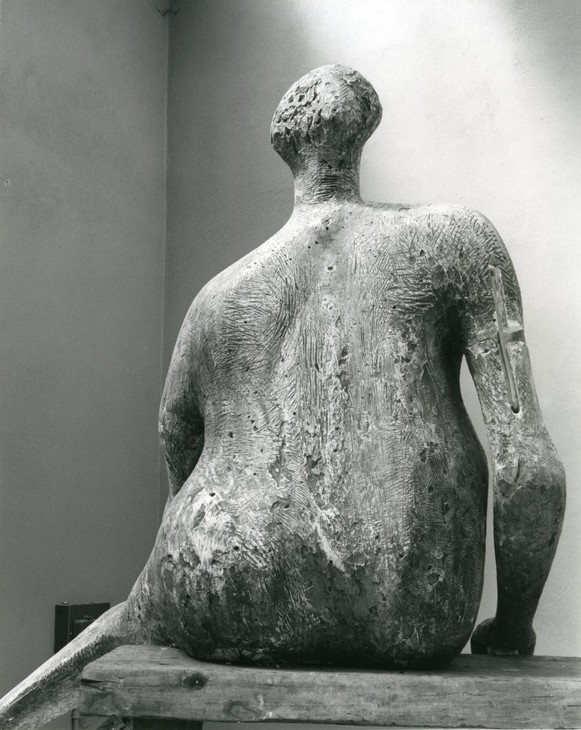

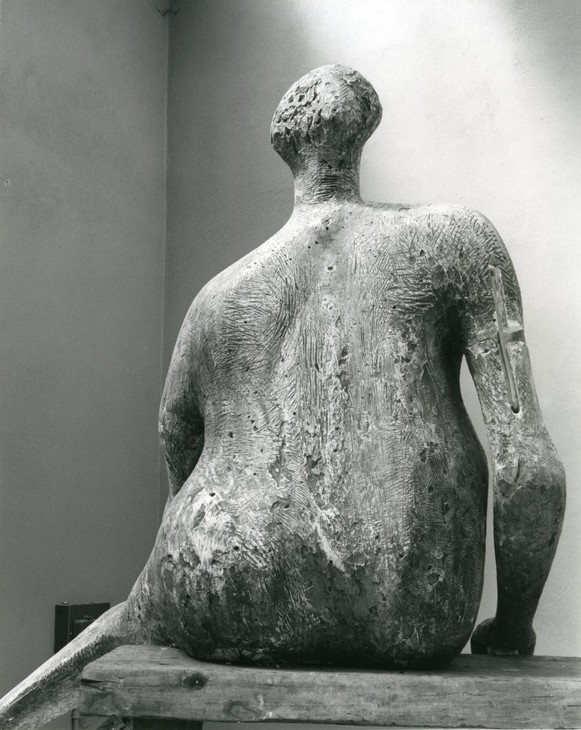

The figure, whose bodily proportions are not anatomically correct, is positioned so that her broad torso sits upright and twists slightly to the right, while her head faces forwards and her legs are angled to the left (fig.1). Moore has arranged the body on a gentle diagonal, which moves from the feet upwards and across the torso to the woman’s right shoulder. Two domed protrusions denote the woman’s breasts, below which the figure’s stomach, which is marked with a large depressed navel, bulges towards the right. From the rear a slightly concave groove can be seen running down the centre of the figure’s broad back, made more prominent by the lighter strip of plaster that runs its length (fig.2).

Henry Moore

Seated Woman 1957 (rear view)

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Seated Woman 1957 (rear view)

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The figure has a long, thick neck that merges into a domed head (fig.3). A thin repair line encircling the neck suggests that the head was once detached from the body. The head has been sparsely modelled with a slightly tilted chin, two circular depressions in the position of eyes, and a subtle, rounded ridge suggestive of a nose. Scratched lines mark the face, and while some seem to suggest eyebrows, others, such as those below the right eye appear to be violent striations. The figure has an asymmetric hairstyle that closely resembles those of other female figures by Moore, with two buns protruding on the left and rear of her head.

The figure’s arms extend from broad shoulders and each taper into thin elbows and wrists. The left arm is bent so that its forearm crosses the torso, and terminates in a loosely clenched fist resting on the figure’s right thigh. The back of the hand is textured with rows of scalloped concave marks that echo the rivets on the knuckles (fig.4). A thumb rests outside the fist but the individual fingers have not been fully modelled. The right arm is also bent but extends downwards adjacent to the body. The right hand has been modelled so that the palm rests on the top of the bench and the fingers, which have been defined only by shallow grooves, wrap around the edge. However, when seen from the side it is evident that the hand actually hovers above the surface of the bench (fig.5). The legs, which like the arms taper to their thinnest point at the extremities, are separated by a large gap but extend to the left at a similar angle. The left and right foot have received only the barest modelling, and rest on their instep and outstep respectively.

Detail of left hand of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of left hand of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of right hand of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of right hand of Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The heavily textured surface of the sculpture demonstrates how layers of plaster were applied and manipulated as they dried (fig.6). The mottled, modulated surfaces of the upper chest area suggest that the plaster was applied with spatulas and palette knives. The plaster on the right arm has been smoothed with a range of files or sandpaper and then scraped with graters to create a dense texture consisting of short parallel lines. Gouged areas, such as the belly and right hip, appear to have been produced by carving directly into the dry plaster. To temper the original, harsh white tone of the plaster Moore applied an uneven wash of light brown or raw umber pigment to the surface. The high points of the sculpture, including the belly, face and backbone, remain lighter than other areas. Pink or fawn shades appear on surfaces that have been repaired, such as around the neck and ankles and on the upper right arm.

Origins and facture

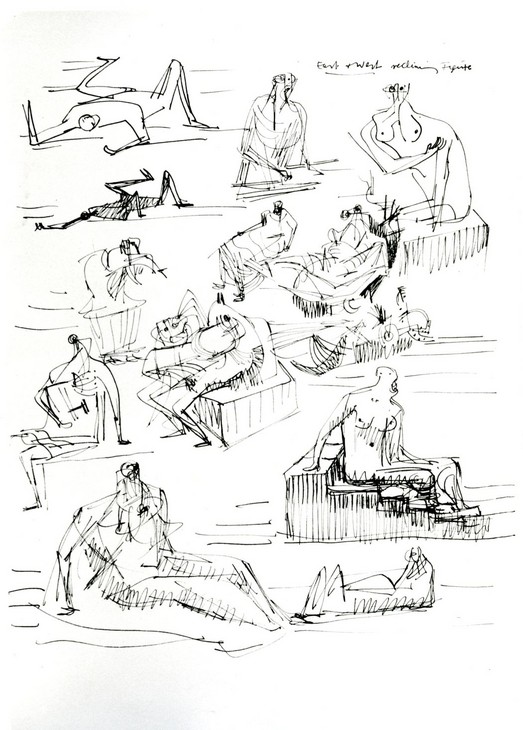

In 1963 Henry Moore discussed with the critic David Sylvester how he generated new ideas for sculptures. When Moore created this work in 1957 he recorded his ideas for sculptures in the form of drawings and sketches. For example, a page from his sketchbook titled Figure Studies 1955–6 (fig.7) illustrates how Moore was considering the form and arrangement of the seated figure in the mid-1950s. However, around this time he began to make fewer preparatory drawings for specific sculptures in favour of small three-dimensional models or maquettes, which allowed him to work out ideas in the round. When Sylvester asked Moore whether he had made preparatory drawings for Seated Figure he replied:

that kind of idea can’t begin from a drawing; in that particular case there is a sort of sense of touch of the back of that figure which is what my mother had when I had to massage her when she suffered from rheumatism. This must have come from actuality, from the handling of the material.1

Moore made the plaster maquette for Seated Woman, titled Maquette for Figure on Steps, in 1956, most likely in the small studio in the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire (fig.8). According to staff at the Henry Moore Foundation it is likely that Moore also used this maquette to create Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956 (Tate T06824; fig.9).2 Moore is known to have reused and reconfigured his plaster maquettes, and the reproducible nature of plaster allowed him to create multiple examples of the same sculpture, which could then be worked up into different designs. The twisted, unevenly weighted torso and angled legs of Maquette for Fallen Warrior bear a strong resemblance to the plaster Maquette for Figure on Steps, and Moore could have easily replaced the arms and head and removed details such as the breasts. The notion that these designs were developed in such close proximity is supported by Figure Studies, which includes two sketches of a supine figure with its legs in the air alongside a series of seated women. The plaster Maquette for Figure on Steps was later cast in an edition of nine bronzes under the title Maquette for Seated Woman and is numbered 434 in the artist’s catalogue raisonné.

Henry Moore

Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

Plaster

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Henry Moore

Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore used Maquette for Figure on Steps as the template for the large-scale sculpture. By systematically charting and measuring specific points on its surface using grids and set-squares, the maquette could be enlarged in plaster while retaining its original proportions. This process was probably carried out in the White Studio at Hoglands or, weather permitting, on the studio terrace. Much of the preliminary enlargement work would have been undertaken by one or more of Moore’s sculpture assistants, who in 1957 included Geoffrey Harris, Daryll Hill, Maurice Lowe and Stephen Rich.

Work on the full-size Seated Woman would have begun with Moore and his assistants constructing an armature from lengths of wood and wire netting cut to the size and shape of the sculpture. This would then have been wrapped in scrim, a bandage-like fabric soaked in wet plaster. Once this layer of scrim had dried, successive layers of plaster could then be built up to the desired depth. Moore found plaster to be a very useful material because it could be ‘both built up, as in modelling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.3 The surface of the sculpture reveals that Moore used an array of tools including trowels, axes and cheese-graters to make different types of markings, grooves and cuts in the plaster as it dried.

Once the plaster was complete it was sent to the Corinthian Bronze Foundry in London to be cast in bronze. The methods most commonly used by professional foundries to cast bronze sculptures – the lost wax and sand casting methods – require an original model from which a mould can be taken. Molten bronze is then poured into this mould to produce a cast. Due to the size of the sculpture, it is likely that the plaster was carved up into smaller pieces so that several, less complex moulds could be made. The individual bronze pieces would then be welded together to create the final sculpture.4

When Moore first started working in plaster he regarded the sculptures as stages towards the production of a bronze and not as artworks in their own right. Plaster sculptures were often returned from the foundry covered in sealants and resins or in pieces. Initially Moore destroyed the plaster originals after a bronze edition had been cast to ensure that no additional, unauthorised sculptures could be produced. However, Moore’s attitude towards his plasters shifted over time, and he began to see them not only as intermediary stages in the creative process but as unique objects with a distinct character. In the early 1970s Moore declared, ‘these are not plaster casts; they are plaster originals ... they are actual works that one has done with one’s hands’.5 Moore went on to recount the moment when he began to reconsider the value of his plasters:

A friend who works at the Victoria and Albert Museum came out one day just as we were breaking up some plasters and said, ‘But why do that, because sometimes the original plaster is actually nicer to look at than the final bronze’. He was right because sometimes an idea you’ve had and that you’ve made in the original material or plaster can suit it better that what the final bronze may do ... So, this led to the idea of not destroying the plasters, leaving me with a great many of them that I would not sell but wanted to find proper homes for.6

Having decided to stop destroying his plasters, Moore was then faced with the problem of what to do with them. Selling them on the open market would increase the risk of casts being made without his permission, but he did not have the required space to keep the plasters indefinitely. A solution was found by way of philanthropic gifts, first to the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto in 1974, and then to the Tate in 1978. In the early 1970s Moore’s studio assistants John Farnham, Michael Muller and Malcolm Woodward set about restoring and repairing the damaged plasters and removing traces of resin sealant from their surfaces. According to the curator at the AGO, Alan Wilkinson, this process demonstrated ‘more clearly the extraordinary variety of surface details and textures, each of the original plasters having its own unique surface colouring and tonality’.7 In the case of Seated Woman Moore’s assistants had to reattach its right arm. A black and white photograph in the Henry Moore Foundation Archive shows that a metal pin was inserted into the arm to hold the two sections together (fig.10). The area of pinkish plaster and the longer, uneven markings on the surface indicate where new plaster and colour was applied during the restoration process (fig.11).

Detail of photograph showing restored plaster on Seated Woman 1957

The Henry Moore Foundation

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Detail of photograph showing restored plaster on Seated Woman 1957

The Henry Moore Foundation

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of photograph showing restored plaster on Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Detail of photograph showing restored plaster on Seated Woman 1957

Tate T02279

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Sources and development

During the 1950s the figure of the solitary, seated female – distinct from the artist’s standing or reclining figures and seated family groups – became a persistent subject of Moore’s sculpture, particularly after 1955.8 In May that year Moore was approached to create a large-scale sculpture for the new headquarters of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) in Paris. Throughout 1955 and 1956 Moore struggled to formulate a design that would express the tenets of Unesco and assert itself against the building’s façade, designed by architect Marcel Breuer. Moore created numerous maquettes for the project, variously presenting a female figure, or groups of figures, seated on steps, or on benches, often set against a wall. Although it is unclear whether the plaster Maquette for Figure on Steps from which Seated Woman developed was seriously considered for the Unesco commission, Moore’s biographer Roger Berthoud identified it as one of eleven maquettes made between 1955 and 1956 that he referred to as ‘the daughters of Unesco’.9

In 1960 the critic Will Grohmann identified two kinds of seated figure in Moore’s work. The first, he argued, conveyed repose and contemplation, while the second expressed ‘the moment before rising, jumping up, going into action’.10 Grohmann suggested that ‘the relaxed figures tend towards the classical, and the tense ones toward the demonic’.11 For Grohmann, ‘the demonic figures ... are continuations of the destroyed and destroying themes that followed the end of the 1930s and the beginning of the 1950s, except that this time the conception is not based on hollow forms and an open framework, but on fully three-dimensional shapes that have been subjected to distortions that exercise a shock effect’.12

Although the pose and soft, rounded forms of Seated Woman make the figure appear placid, Grohmann considered the sculpture to be an example of the ‘demonic’ type. Discussing the work under the title ‘Unclothed Seated Figure’, he noted that at first glance the sculpture looks ‘almost healthy and countrified; but there is an unrest quivering in the sculptural emphasis of certain parts, the abdomen and upper left arm for example’.13 That Grohmann should have related this work to ‘destroyed and destroying themes’ is insightful given the work’s formal relationship to Maquette for Fallen Warrior, one of the few works in which Moore overtly addressed the subject of physical violence. Grohmann also proposed that these same themes linked Seated Woman with Moore’s Woman 1957–8 (Tate T02280; fig.12), the limbs of which appear to have been forcibly amputated. Moore also drew connections between the two sculptures, but on more general formal grounds. In 1968 he stated, ‘right from the beginning I have been more interested in the female form that in the male. Nearly all my drawings and virtually all my sculptures are based on the female form ... Woman and Seated Woman ... both have the big form that I like my women to have’.14

Henry Moore

Standing Figure: Back View c.1924

Pen and ink, brush and ink, chalk and wash on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Standing Figure: Back View c.1924

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Cézanne’s figures had a monumentality about them that I liked. In his Bathers, the figures were very sculptural in the sense of being big blocks and not a lot of surface detail about them. They are indeed monumental but this doesn’t mean fat. It is difficult to explain this difference but you can recognize a kind of strength. This is a quality which you see only if you are sensitive to it. It’s to do with the full realisation of the three-dimensional form; colour change comes into that too, but not so importantly as human perspective.

Bathers is an emotional painting but not in a sentimental way. Cézanne had an enormous influence on everyone in that period, there was a change in attitudes to art. People found him disturbing because they didn’t like their existing ideas being challenged and overturned. Cézanne was probably the key figure in my lifetime.17

Bathers is an emotional painting but not in a sentimental way. Cézanne had an enormous influence on everyone in that period, there was a change in attitudes to art. People found him disturbing because they didn’t like their existing ideas being challenged and overturned. Cézanne was probably the key figure in my lifetime.17

The strength and maturity of Cézanne’s women may have reminded Moore of what Wilkinson has described as one of his ‘earliest and most important tactile sensations ... rubbing his mother’s back with liniment, to ease the pain of her rheumatism’ as a young boy.18 Moore had suggested to Sylvester in 1963 that his memory of massaging his mother’s back may have informed how he modelled Seated Woman, and in 1968 he elaborated on the connection:

Seated Woman, particularly her back view, kept reminding me of my mother, whose back I used to rub as a boy when she was suffering from rheumatism. She had a strong, solid figure, and I remember, as I massaged her with some embarrassment, the sensation it gave me going across her shoulder blades and then down and across the backbone. I had the sense of an expanse of flatness yet within it a hard projection of bone. My mother’s back meant a lot to me.19

The psychologist Erich Neumann argued in 1959 that ‘the dominant factor in the haptic experience of the child, to which Moore’s art reverts, is the peculiar hierarchy of magnitudes in which the subject feels small, dependent, and attached, and the mother’s body feels like a great world, the source of life and warmth’.20 Neumann proposed that the maternal aspects of Moore’s large women related to those of the archetypal ‘Great Mother’, a symbol of ‘nourishment, shelter and security’ and ‘the mistress of life and fertility’.21 The identification of Seated Woman as a symbol of fertility may be particularly germane given that Moore suggested that the figure may represent a pregnant woman. In March 1958 Moore updated a client, Alan Wurtzburger, on the progress of a number of sculptures, writing in his letter that he had enclosed ‘photographs of the “Seated Woman”, now in bronze. I think at one time I called her “Pregnant Woman”, but I am leaving that out of its title now’.22 Although he decided to change the sculpture’s title Moore was clearly comfortable for the figure to be identified as pregnant, and later linked the work to the experiences of his own family. In 1968 he stated, ‘Seated Woman is pregnant. The fullness in her pelvis and stomach is all to her right. I don’t remember that I consciously did it this way, but I remember Irina telling me, before Mary was born, that sometimes she could feel that the baby was on one side and sometimes on the other’.23

For Neumann, however, Moore’s representation of pregnancy exceeded the scope of his family. He proposed that the ‘Great Mother’ was at the centre of all ancient civilisations and a fundamental trope of human consciousness, arguing that:

the sovereign power of motherhood determined the earliest phase of man’s development, and only later, with the growth of consciousness, was it superseded and overlaid by the significance of the father and the patriarchal values connected with the father archetype. Today a new shift of values is beginning, and with the gradual decay of the patriarchal canon we can discern a new emergence of the matriarchal world in the consciousness of Western man.24

A central tenet of Neumann’s thesis was that Moore’s turn to the archetypal Mother Earth was not simply a matter of personal choice, but one manifestation of a widespread social tendency in the post-war period which sought to disassociate itself from the patriarchal structures that had led to war.

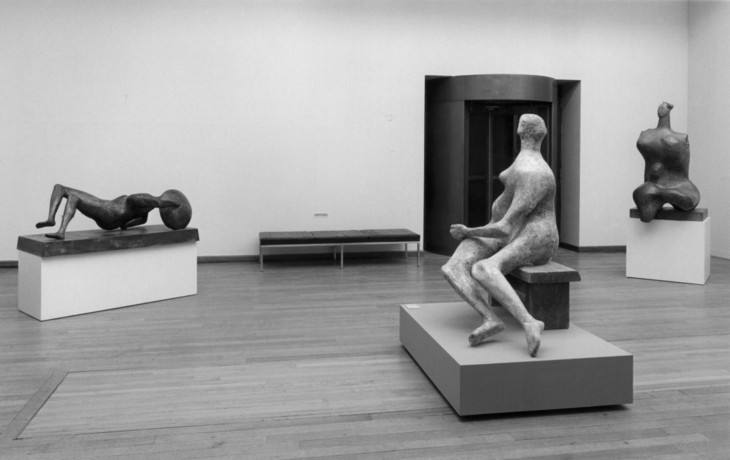

The Henry Moore Gift

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Alice Correia

November 2013

Notes

Henry Moore cited in David Sylvester, ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–6.

James Copper, Sculpture Conservator at The Henry Moore Foundation, in conversation with the author, 31 July 2013.

Seated Woman was cast in an edition of six plus one artist’s copy. Casts are held in the collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City; the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington D.C.; and the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.18.

Roger Berthoud cited by Julie Summers, ‘Working Model for Draped Seated Woman: Figure on Steps 1956’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.253.

Henry Moore cited in Hew Wheldon (ed.), Monitor: An Anthology, London 1962, pp.21–2, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.147.

Henry Moore quoted in John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore. My Ideas, Inspiration and Life as an Artist, London 1986, pp.150–1. For an image of Paul Cézanne’s The Large Bathers 1900–6 see http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/104464.html , accessed 23 May 2014.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Erich Neumann on Henry Moore: Public Sculpture and the Collective Unconscious Tim Martin

Related catalogue entries

Related material

Related bibliography

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Seated Woman 1957 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www