Henry Moore OM, CH Maquette for Family Group 1945

Image 1 of 12

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Family Group 1945© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Maquette for Family Group

1945

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

This small sculpture presenting a family group was originally conceived by Henry Moore as a preparatory model for a large sculpture in bronze. It is one of a series of works made in the mid-1940s that address the subject of the family, and is a rare example of Moore’s attempt at composing a four-figure sculpture.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Maquette for Family Group

1945

Bronze

178 x 102 x 60 mm

Inscribed ‘MOORE’ on the side of base

Purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries (Knapping Fund) 1945

In an edition of 7 plus 1 artist’s copy

N05606

Maquette for Family Group

1945

Bronze

178 x 102 x 60 mm

Inscribed ‘MOORE’ on the side of base

Purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries (Knapping Fund) 1945

In an edition of 7 plus 1 artist’s copy

N05606

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries (Knapping Fund) in 1945.

Exhibition history

?1945

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, Berkeley Galleries, London, March–April 1945.

1972

Painting, Sculpture and Drawing in Britain 1940–49, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, November 1972.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1998

Special Exhibitions: Henry Moore, Imperial War Museum, London, September–November 1998.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.32.

2007

Moore and Mythology, The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green, April–September 2007, no.14.

References

1946

James Johnson Sweeney, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1946 (another cast reproduced no.56).

1948

David Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture II’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.544, July 1948, p.193.

1957

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, London 1957, no.238, p.15.

1961

Henry Moore: Sculpture & Drawings from Sir Kenneth Clark’s Collection, exhibition catalogue, Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh 1961 (another cast reproduced no.9).

1972

Painting, Sculpture and Drawing in Britain 1940–49, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1972.

1976

Henry Moore Bronzes and Drawings: A Selection from our Collection, exhibition catalogue, Fischer Fine Art, London 1976 (another cast reproduced no.3).

1978

Erich Steingräber, Henry Moore Maquetten, Munich 1978 (terracotta reproduced p.24).

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.63.

2007

David Mitchinson (ed.), Moore and Mythology, exhibition catalogue, The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green 2007, reproduced p.19.

Technique and condition

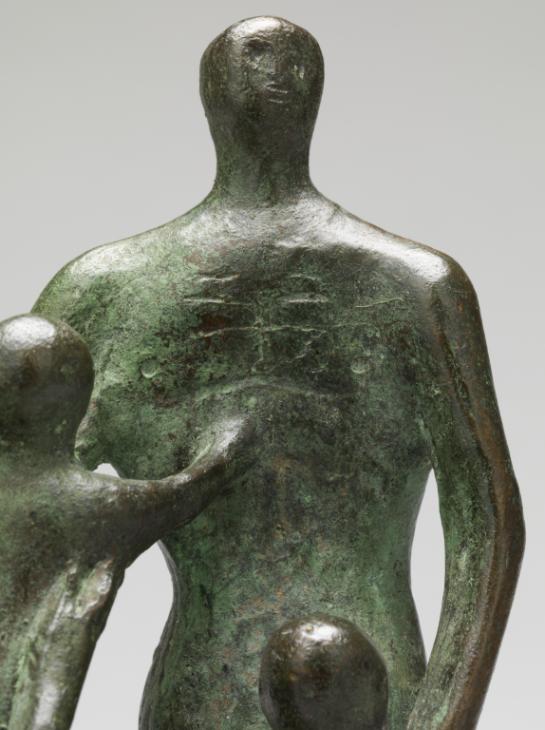

This maquette of a seated woman and standing man with two children is a solid bronze cast with no hollow cavity (fig.1). The original model for this sculpture was made in clay and would have been used to make a mould from which the final bronze version could be cast. Moore made small impressions into the clay model to denote facial features, fingers and details on the man’s chest that are replicated in the bronze sculpture. A deep crack in the woman’s lap may be a cast of a drying or firing crack. The level of surface detail on the bronze suggests that it was made using the traditional lost wax casting technique. Apart from the casting seam visible on the left leg of the child on the ground, which continues onto the base, there is otherwise little evidence of post-cast finishing.

The bronze surface has been coloured using chemical patination techniques. First, a slightly transparent brown colour was applied over the surface, followed by a more opaque green colour, which was then rubbed back on high points using a light abrasive to pick out the details of the form. The patina was then finished with a coating of wax. The brown base colour is often used on bronzes and is likely to have been applied using a solution of potassium polysulphide (otherwise known as ‘liver of sulphur’) in water. There are many different patina recipes used to produce green colours on bronzes but they often contain mixtures of copper and ammonium salts.

Henry Moore

Maquette for Family Group 1945

Tate N05606

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Maquette for Family Group 1945

Tate N05606

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of artist's signature on Maquette for Family Group 1945

Tate N05606

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of artist's signature on Maquette for Family Group 1945

Tate N05606

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The signature ‘MOORE’ was inscribed on the base behind the woman’s stool using a sharp point, possibly into the clay model or the pre-cast wax (fig.2). The maquette is generally in good condition.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Maquette for Family Group 1945 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Maquette for Family Group is one of at least fourteen small models made by Henry Moore in the mid-1940s, each of which presents a family group in different poses and configurations. This sculpture presents a seated mother, a standing father, and two children as an embracing and supportive family unit (fig.1). The mother sits on a low rectangular stool while the father stands tall at a right angle to her, with his right hand on her left shoulder. A larger, probably older, child stands opposite the mother and rests its arms on her knees. The father’s left hand rests on this child’s back while the smaller child stands on the mother’s right thigh, and is supported by her as it reaches upwards towards the father. Moore has used the arms of each figure to establish a sense of union, exemplified by the father’s arms, which envelop the whole group.

The origins of this sculpture lie in the mid-1930s when the German architect Walter Gropius proposed to Moore that he make a large-scale sculpture for a school in Impington, near Cambridge, which was designed by Gropius and Maxwell Fry in 1935–6 and opened in 1939. The college was designed to be a flexible space that catered for all the family, acting as the focal point for the entire community.1 Moore later recalled discussing the commission with Henry Morris, Chief Education Officer for Cambridgeshire County Council:

we talked and discussed it, and I think from that time dates my idea for the family as a subject for sculpture. Instead of just building a school, he was going to make a centre for the whole life of the surrounding villages, and we hit upon this idea of the family being the unit that we were aiming at.2

In 1951 Moore wrote that,

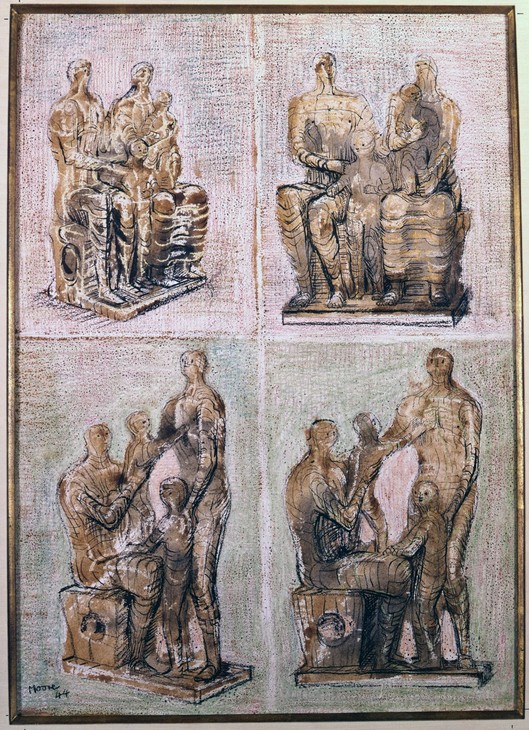

later the war came and I heard no more about it until, about 1944, Henry Morris told me that he now thought he could get enough money together for the sculpture if I would still like to think of doing it. I said yes, because the idea right from the start had appealed to me and I began drawings in note book form of family groups. From these note book drawings I made a number of small maquettes, a dozen or more.3

Henry Moore

Family Groups 1944

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink on paper

559 x 381 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Family Groups 1944

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The original three-dimensional model for this sculpture was made in clay. This model was then used to make a mould of the maquette, which was filled with molten bronze to create the final solid sculpture. In addition to this maquette, Moore made at least thirteen other clay models of family groups.6 Ten of these models were cast in bronze editions, three of which are held in the Tate collection (see also Tate N05604–N05605).

Maquette for Family Group was cast at the Art Bronze Foundry, London, in an edition of seven plus one artist’s copy. Notes made by Moore for the owner of the foundry, dated ‘March 28’, identify three Family Group maquettes for casting, along with five maquettes for Moore’s Madonna and Child, which date from 1943.7 The inclusion of this Maquette for Family Group suggests that Moore made these casting notes in 1945. It is number seven on the list, and a small sketch of the work is annotated with the phrase ‘Family Group. Standing Man (4 figures)’. The notes indicate that eight bronze examples were wanted, and that two examples of this particular maquette had been cast and delivered to an unnamed gallery by 28 March. It is likely that the gallery mentioned on the note was the Berkeley Galleries, London, where Moore had an exhibition in March–April 1945.

In an article published in the Burlington Magazine in July 1948, Sylvester, who had worked as Moore’s personal assistant in 1945, noted that ‘Moore had always made maquettes for his larger sculptures, but it was not until he cast about half-a-dozen of the ten or so clay studies for the Northampton Madonna that he began to make bronzes of them’.8 The bronze maquettes of family groups were produced to be sold privately and were probably cast to provide an income in case the Impington commission failed to materialise. Moore’s decision to make multiple bronze casts drastically altered the type of work he was able to produce, and provided more opportunities to sell his work. Bernard Meadows, who was Moore’s studio assistant at the time, later recalled that ‘most of these little family groups were sold for £35 (having cost about £12 to cast) so he [was] making just over £20 per sculpture’.9

In 1994 Meadows recalled that after the newly cast bronze maquettes were returned to Moore from the foundry they required a lot of finishing work:

He [Moore] wasn’t very satisfied with Gaskin’s casts [Charles Gaskin was the owner of the Art Bronze Foundry]. They were pretty rough, they were pretty bad and some of them, I said to him, ‘well you ought not accept that’. But he went ahead, he was half worried about upsetting any of these foundry chaps because where would he get them cast here in Britain? ... they were in such a state that one had to get them back to some semblance of acceptability ... the bronzes had to be worked on and then they had to go back to the foundry to be patinated.10

Moore and the Tate Collection

This sculpture was one of three bronze family group maquettes bought by Tate in 1945 and is thus one of the earliest works by Moore to have been purchased for the Tate collection. The purchase of these works illustrated the desire of the director Sir John Rothenstein to represent Moore’s work in the collection. In contrast, Rothenstein’s predecessor, J.B. Manson, had previously told the Tate trustee Robert Sainsbury ‘over my dead body will Henry Moore ever enter the Tate’.11 Rothenstein’s appointment thus signalled a shift in the direction of Tate’s ambitions. One of his first actions as director had been to accept the donation from the Contemporary Art Society of Moore’s Recumbent Figure 1938 (Tate N05387). Then in 1941 Rothenstein encouraged the appointment of Moore to Tate’s Board of Trustees.

In 1944 Rothenstein wrote to Moore asking whether Tate could commission a large carving based on one of his Madonna and Child maquettes (see Tate N05602). Moore politely turned down the suggestion, writing ‘its now more than a year since these little figure studies were done, + that’s whats [sic] making me hesitate now over your suggestion – for it would mean putting my mind back in working to a year ago’.12 Instead, Moore suggested that the Tate might be interested in some of the studies for a ‘Family Group’ he had recently begun working on. This proposal was accepted and Tate bought four maquettes for the Madonna and Child and three maquettes for the Family Group.

The three maquettes for Family Group were purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries in early 1945 with money from the Knapping Fund.13 The Knapping Fund was the residuary estate of Miss Helen Knapping bequeathed to the Trustees of the National Gallery in 1935 to be spent on work by living or recently deceased British artists. A fraction of this money was allocated to the Tate by the National Gallery, as Tate’s purchasing power continued to rely on charitable donations and private patronage until well after the Second World War.

As Moore suspected, Henry Morris was ultimately unable to secure financial backing and institutional support for the Impington commission. However, in 1947 Moore enlarged one of his other family group maquettes (Tate N05605) for Barclay Secondary School in Stevenage, Hertfordshire. A bronze cast of this large sculpture (Family Group 1949, Tate N06004) was acquired by Tate in 1950. In 1954–5 Moore then carved an enlarged version of another family group maquette (Tate N05604), which was installed in Harlow in 1956.

Alice Correia

March 2014

Acknowledgements

This catalogue entry was compiled from research undertaken by Robert Sutton, Collaborative Doctoral Award student (University of York and Tate).

This catalogue entry was compiled from research undertaken by Robert Sutton, Collaborative Doctoral Award student (University of York and Tate).

Notes

See Harry Rée, Educator Extraordinary: The Life and Achievement of Henry Morris, London 1973, pp.70–2.

Henry Moore cited in Farewell Night, Welcome Day, television programme, broadcast BBC, 4 January 1963, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.89.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, broadcast BBC Radio, 14 July 1963, Tate Archive TGA 200816, p.13. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

See David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, 1957, 5th edn, London 1988, pp.14–15.

See Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Drawings 1940–49, Much Hadham 2001, p.195, no.43.105.

David Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture II’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.544, July 1948, p.190.

Related essays

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Henry Moore and the Welfare State Dawn Pereira

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

- ‘A sincere academic modern’: Clement Greenberg on Henry Moore Courtney J. Martin

- ‘Worthy of the great tradition’: Kenneth Clark on Henry Moore Chris Stephens

Related catalogue entries

Related material

Related bibliography

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Maquette for Family Group 1945 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www