Henry Moore OM, CH Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60

Image 1 of 14

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Falling Warrior 1956-7, cast c.1957-60© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Falling Warrior

1956-7, cast c.1957-60

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Falling Warrior is one of only six large-scale male figures created by Moore. Three of these male figures exist within family groups, while the remaining three, including Falling Warrior, present the male body as wounded and fragile. This sculpture illuminates Moore’s interest in ancient Greek sculpture while possibly alluding to the suffering caused by the Second World War.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Falling Warrior

1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Bronze

650 x 1540 x 850 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02278

Falling Warrior

1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Bronze

650 x 1540 x 850 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02278

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1960

Contemporary British Sculpture 1960, organised by the Art Council, Cannon Hill Park, Birmingham, April–May 1960, no.20.

1960

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Kunstverein Hamburg, Hamburg, May–July 1960; Museum Folkwang, Essen, July–August 1960; Kunsthaus Zürich, Zürich, September–October 1960; Haus der Kunst, Munich, November–December 1960, no.43.

1960–1

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, November 1960–January 1961.

1961–2

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Galleria Nazionale de Arte Moderna, Rome, January–February 1961 (no.38); Musée Rodin, Paris, March–April 1961 (no.37); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, June–July 1961 (no.37); Akademie der Künste, Berlin, July–September 1961 (no.38); Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Vienna, September–October 1961 (no.36); Louisiana Museum, Humlebaek, December 1961–January 1962 (no.36).

1962

Henry Moore: Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, October–November 1962, no.25.

1964

Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore at King’s Lynn, St Margaret’s Church, King’s Lynn, July–August 1964, no.11.

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, City Art Gallery, Plymouth, June–July 1966, no.31.

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.99.

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, 1969, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, August–October 1969, no.41.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972, no.98.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1981–2

British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century. Part Two: Symbol and Imagination 1950–80, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, November 1981–January 1982, no.37.

1982–3

Henry Moore en México: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, November 1982–January 1983, no.75.

1983

Henry Moore: Esculturas, Dibujos, Grabados – Obras de 1921 a 1982, Museum of Contemporary Art, Caracas, March 1983, no.34.

1983

Henry Moore: Winchester 1983, Winchester Castle, Winchester, July–September 1983, no number.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.138.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, March–August 1998, no.79.

2007–8

Moore and Mythology, Musée Bourdelle, Paris, October 2007–February 2008, no.129.

2010

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010, no.139.

2013–14

Bacon / Moore: Flesh and Bone, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, September 2013–January 2014.

References

1958

David Sylvester, ‘A New Bronze by Henry Moore’, Listener, 10 July 1958, p.51.

1958

A Sculptor’s Landscape, dir. by John Read, television programme, broadcast BBC, 29 June 1958, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8802.shtml, accessed 22 January 2014.

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, pp.217–8 (detail reproduced pl.168).

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1960, reproduced no.50.

1960

Lawrence Alloway, ‘London Letter’, Art International, vol.4, no.10, December 1960, p.50.

1962

Henry Moore: Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1962, pl.14.

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, pp.208–9, reproduced pl.192.

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.22.

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, City Art Gallery, Plymouth 1966, reproduced on front cover.

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, pp.127–8, reproduced pl.120 and detail pl.122.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.139, reproduced pl.136.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, p.279, reproduced pp.276–9.

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, reproduced pls.538–40.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence 1972, reproduced p.167.

1973

Henry Moore: The Language of Sculpture, dir. by John Read, television programme, broadcast BBC2, 1 January 1974, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8810.shtml, accessed 22 January 2014.

1975

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1975, pp.152–61, reproduced pls.76–8 and 84.

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.34.

1979

John Read, Portrait of an Artist: Henry Moore, London 1979, p.112.

1981

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2278 Falling Warrior 1956–7’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.123–24.

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983 (another cast reproduced p.84).

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, no.405, reproduced pls.28–31.

1988

Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998, reproduced pp.228–9.

2000

Roger Cardinal, ‘Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece’, Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, pp.17–51 (another cast reproduced no.22).

2006

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona 2006 (another cast reproduced p.146).

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (another cast reproduced p.71).

2007

David Mitchinson (ed.), Moore and Mythology, exhibition catalogue, The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green 2007 (another cast reproduced no.104).

2008

Jon Wood and Bruce McLean, ‘Fallen Warriors and a Sculpture in My Soup: Bruce McLean on Henry Moore’, Sculpture Journal, vol.17, no.2, 2008, pp.116–124, reproduced p.119.

2008

Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, pp.140–6, reproduced fig.369.

2010

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced p.196.

2013

Richard Calvocoressi, Martin Harrison and Francis Warner, Bacon / Moore: Flesh and Bone, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 2013 (another cast reproduced).

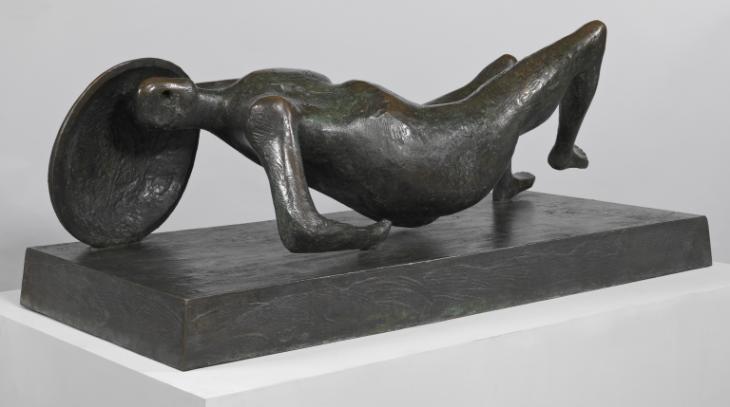

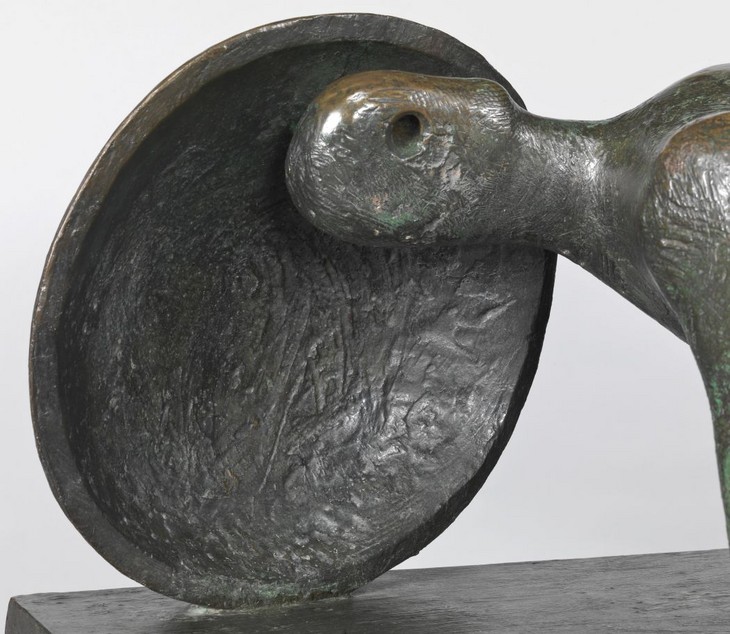

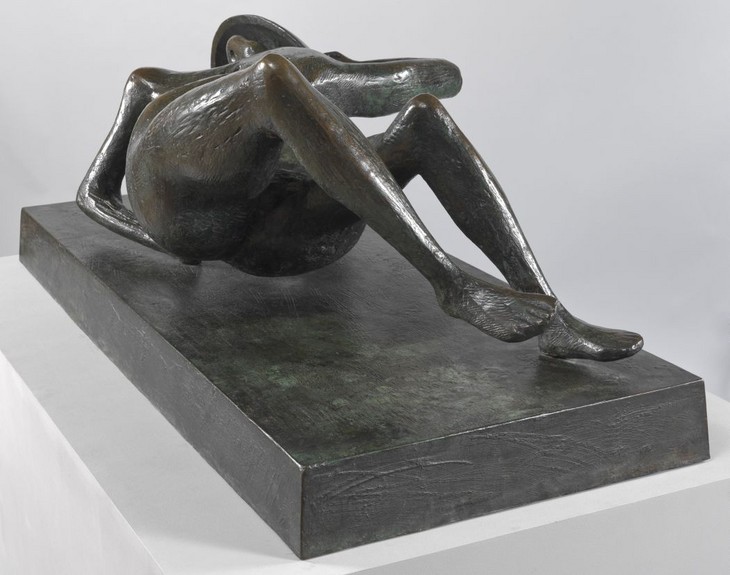

Technique and condition

This bronze sculpture represents a naked male figure in a horizontal position lying on or falling towards the ground. The figure holds a circular shield up to his head in his left hand and is supported on a rectangular bronze base with trapezoid sides. The bronze surface of the sculpture is highly textured with a variegated green colour punctuated with brown highlights. Moore represented the man’s eye by piercing a hole right through the head (fig.1).

Moore would have first made this sculpture in plaster from which a mould would have been taken to cast the final version in bronze. He would have built the wet plaster up in stages over a supporting framework called an armature, probably made from metal or wood. When the plaster was set, Moore could then work the surface by carving, filing, scraping and gouging to achieve the final texture reproduced in the bronze. Close examination of the surface reveals investment trapped in small crevices (fig.2), which shows that this bronze figure was cast using the traditional lost wax technique, probably in one piece. The surface has been left as it was cast except for the removal and chasing of casting flashes and seams with files and chasing tools. The shield was cast separately and welded onto the figure’s left hand (fig.3). The bronze casting was carried out at the Fiorini Art Bronze Foundry in London in an edition of ten plus one artist’s copy. There is no inscription visible.

Detail of Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60 showing casting investment

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60 showing casting investment

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of welding join between the left hand and shield of Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of welding join between the left hand and shield of Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The base was cast separately, probably using the sand casting method. It is textured on the top and sides through a combination of techniques that appear to have involved applying some textile to the surface of the original model for the base, and then scratching a series of parallel lines into the mould itself so that these scratches appear in the final cast as raised lines (fig.4). The figure is attached to the base through bolts inserted from the underside through the right hand, left foot and shield.

Detail of textured base of Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of textured base of Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of green and brown patina on Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of green and brown patina on Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The sculpture was artificially patinated using a range of chemical solutions that reacted with bronze to produce coloured compounds (fig.5). The first colour to be applied would have been a light transparent brown colour, often produced by using a solution of potassium polysulphide (or ‘liver of sulphur’). Following this, the more opaque green colour would have been applied over the top. Many different patina recipes can be used to produce green colours on bronzes but they often contain mixtures of copper and ammonium salts. The cold solution was probably stippled using a brush. Each successive application would be left to dry and develop to build up the opaque green colour. The green would then be rubbed back slightly at high points in order to highlight and give depth to the surface texture. The sculpture would then have been waxed with a clear wax to consolidate and protect the patina.

There are other casts in this edition that have a greener patina but as Tate acquired this sculpture twenty years after it was first made, it seems likely that during the intervening period the surface of the sculpture was regularly handled and therefore lost some of the green colour on the high points.

Lyndsey Morgan

October 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', October 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, February 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

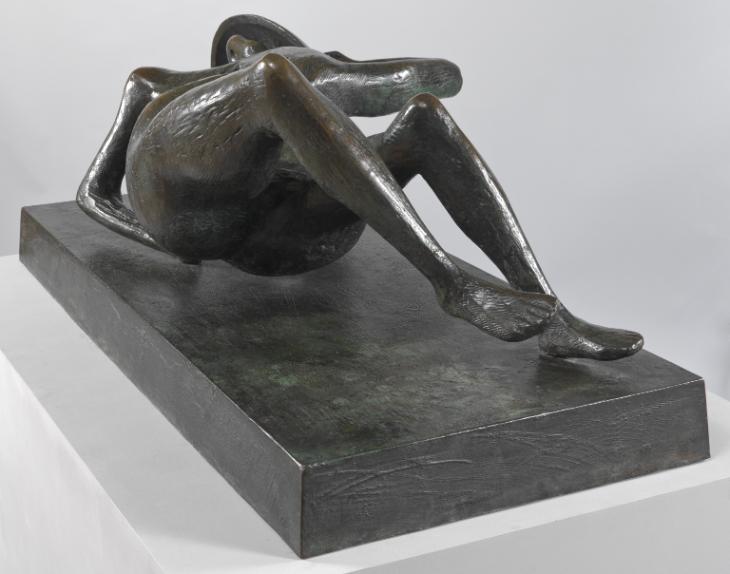

This sculpture depicts an almost life-size male figure positioned horizontally over a rectangular base. The figure holds a circular shield in his left hand, which is drawn up towards his head, and appears to be suspended in motion, hovering just above the base. The sculpture is attached to the base at three points: the left heel, the right hand, and the shield.

Although the figure is recognisably a human male, Falling Warrior is not represented naturalistically. The arms and legs are particularly thin and the head is disproportionately small when compared to the larger, bulbous belly and buttocks. When seen from the head and the foot of the base, the figure seems to twist at the waist, so that the left shoulder and the right hip are both higher than their counterparts (fig.1). In addition, the sculpture has not been positioned squarely within the limits of the base; instead the body is curved, with the head and the feet placed towards the rear of the base, and the hips positioned towards the front.

Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60 (view from head)

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60 (view from head)

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of head of Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of head of Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The head is represented by an oval disk, which is pierced by a single hole that creates a short tunnel linking the left and right sides of the face (fig.2). This hole appears to denote the eyes of the figure, but no other facial features have been represented apart from a slight upwards curve that distinguishes the chin from the neck.

The neck leads to an undulating upper chest, the left side of which swells while the right side dips to create a shallow hollow. From these differing forms the stomach swells to a rounded peak, which dips sharply to the figure’s genitalia. Two nipples and a navel have been denoted by round recessions on the chest and stomach and a penis has been modelled. The downward momentum of the sculpture is achieved through the enlargement of the belly and buttocks, which hang low, hovering just about the surface of the base. The weight of the sculpture seems to have amassed in these large curved areas. The heavy middle of the figure is accentuated by the slender limbs, a contrast that heightens the sense that the figure is falling, as the title suggests.

From the left side of the chest, the left shoulder appears to be in an anatomically incorrect position, and the left arm, which is raised horizontally above the head, seems to be impossibly twisted. Nonetheless, the thin left arm extends to the hand, which is holding the outside of a round, curved shield. The inside of the shield creates a protective concave hollow for the figure’s head.

The bony right shoulder seems to protrude from under the figure’s skin and extends downwards to a thin arm, which is bent at the elbow. The forearm extends on a slight downwards diagonal and terminates in a clenched hand, which rests on the base, as though softening the fall.

The knees of both legs are bent and drawn towards the body; the right leg is suspended in the air and the right knee is the highest point of the sculpture (fig.3). The frontal planes of the right and left thighs are fairly straight, while the undersides have a slight curve where they meet the lower buttocks. From each knee the calves of the legs extend to narrow ankles and heels. The shins of both legs create a slight ridge down the front of the calves. The feet widen at the toes, which are denoted on each foot by incised lines, but which have not been individuated separately. The heel of the left foot rests on the base while the rest of the foot is lifted away from it.

Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60 (view of legs)

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60 (view of legs)

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of polished high points of Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of polished high points of Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The base colour of the sculpture is a very dark brown-black, on top of which green and brown shades have been applied. These green and brown colours have been used to highlight and accentuate certain areas of the sculpture. For example, the ridge of the face, the right shoulder and the top of the belly all have a golden-brown shine to highlight these exposed outer areas (fig.4). In contrast, the underside of the left arm and the inner right thigh are tinged with green. The surface of the bronze is highly textured with lines and scratches. In some instances, such as on the shins and the right forearm, the lines run along the limb accentuating its length and suggest directional movement.

Before embarking on the construction of the full-size sculpture, Moore first created a small maquette in plaster in order to test the three-dimensional design. It is probable that Moore made this model in his maquette studio in the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. Although the original plaster maquette has not survived, it was cast in a bronze edition, probably in late 1956 or early 1957. Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956 (Tate T06824; fig.5) presents a supine male warrior with a shield, but there are significant differences between this work and the final Falling Warrior: in the smaller maquette the figure’s body is in contact with the base (which has two tiers) and thus depicts the moment of the body’s impact with the ground, hence the past participle ‘fallen’ in the title. Furthermore, the shield has been placed next to the feet of the figure in Maquette for Fallen Warrior, whereas in the larger Falling Warrior it is positioned near the figure’s head.

Henry Moore

Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast c.1956–7

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast c.1956–7

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photograph of an early stage in the creation of the full-size plaster version of Falling Warrior, c.1956

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Photograph of an early stage in the creation of the full-size plaster version of Falling Warrior, c.1956

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

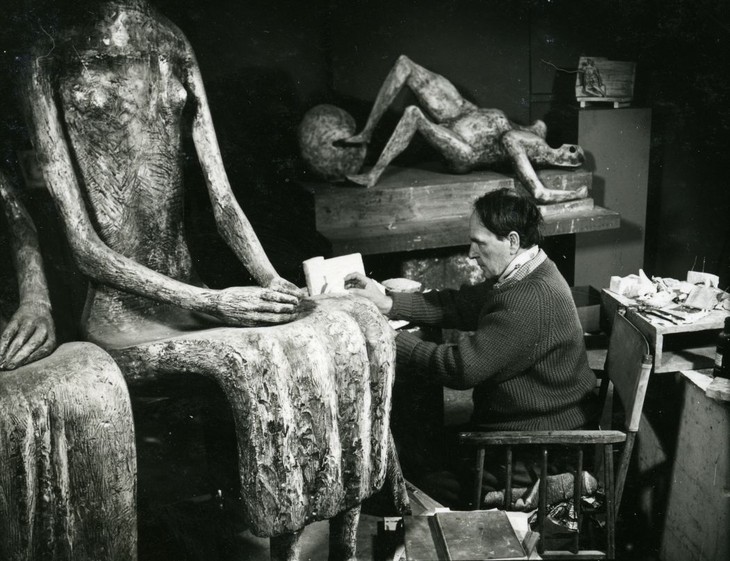

However, it was from this small maquette that Falling Warrior was nonetheless developed, and the next stage in Moore’s creative process was to enlarge the plaster maquette to its full size. A series of at least five black and white photographs, probably taken by Moore himself, document the development of the plaster sculpture from different angles and have been published in a number of books to illustrate the evolution of the work (see fig.6).1 In conversation with Tate researcher Richard Calvocoressi on 12 December 1980, Moore reflected that these photographs ‘often appeared more directly expressive of his intentions than the finished sculpture’.2 In his 1981 catalogue entry for the work, Calvocoressi explained that ‘there were occasions such as this when he [Moore] would have liked to have taken a cast of the work in progress’.3

In order to make the full-size plaster Moore first constructed an armature in wire and wood. In 1960 Moore explained, ‘You need an armature because, with plaster sculpture, you have to build on something or you’d have a great big solid piece of plaster which is unhandleable ... so one makes an armature in wood with, perhaps chicken wire roughly to shape’.4 This armature would form the basic shape of the sculpture and act as an internal support. The armature was then wrapped in lengths of scrim, a bandage like fabric, which had loose webbing to allow the plaster to soak through. Layers of plaster would be applied to the fabric and, once dry, Moore could then begin to model the forms and shapes of the sculpture using the original, smaller maquette as a guide. According to Moore, ‘The advantage of using plaster is that it can be both built up, as in modelling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.5

Henry Moore in his studio with full-size plaster version of Falling Warrior 1956–7

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: John Hedgecoe

Fig.7

Henry Moore in his studio with full-size plaster version of Falling Warrior 1956–7

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: John Hedgecoe

In the Falling Warrior sculpture I wanted a figure that was still alive. The pose of the first maquette was that of a completely dead figure and so I altered it to make the action that of a figure in the act of falling, and the shield became a support for the warrior, emphasising the dramatic moment that precedes death.7

Having decided that he wanted to change the composition of the warrior, it seems unlikely that Moore would have started the full-size model again from scratch. Although not an easy job, it is probable that Moore adjusted and reconfigured the existing plaster; the right arm of the bronze seems to have the same shape as the left arm of the plaster. If Moore did swap the arms of the sculpture over, this would explain the strange twisted shoulders and arms of the final bronze. Moore’s statement also suggests that he had not intended to create two different warrior sculptures, and that the titles of the maquette and the larger bronze were probably given retrospectively in order to distinguish between the two.

Having settled on the composition and completed his recomposed full-size plaster, Moore employed the Fiorini Art Bronze Foundry in London to cast Falling Warrior. According to records held at the Henry Moore Foundation the bronze edition was cast between 1957 and 1960.8 Moore had previously commissioned Fiorini to cast his Family Group 1949 (Tate N06004), and although the foundry had had problems casting this large sculpture, Moore nonetheless continued to use them throughout the 1950s.

It is likely that this sculpture was cast using the lost wax technique, which involved first creating a mould of the plaster sculpture into which molten wax could be poured to create a perfect wax replica of the sculpture. After hardening, the wax replica would then be encased in a hard refractory material and placed in a kiln. Tubular channels within the casing would allow the wax to drain away when it melted, leaving a hollow cavity into which molten bronze would be poured. For the finished bronze sculpture to be flawless the bronze had to be poured in one go. Once the bronze had cooled and hardened the casing could be removed to reveal the finished sculpture.9

After casting at the foundry the bronze sculpture would probably have been returned to Moore so that he could check the quality of the casting and make decisions about the patination. A patina refers to the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze sculpture. In 1960 Moore explained:

I like working on all my bronzes after they come back from the foundry. A new cast to begin with is just like a new-minted penny, with a kind of slight tarnished effect on it. Sometimes this is right and suitable for a sculpture, but not always. Bronze is very sensitive to chemicals, and bronze naturally in the open air (particularly near the sea) will turn with time and the action of the atmosphere to a beautiful green. But sometimes one can’t wait for nature to have its go at the bronze, and you can speed it up by treating the bronze with different acids which will produce different effects. Some will turn the bronze black, others will turn it green, others will turn it red.10

According to curator Julie Summers, Moore sought to ‘produce a unity between patina and form’ in his sculptures, so that the colours complimented the shapes on which they were applied.11 Moore noted that when working on his plasters he normally had a preconceived idea of what colour the sculpture would eventually take:

I usually have an idea, as I make the plaster, whether I intend it to be a bark or a light bronze, and what colour it is going to be. When it comes back from the foundry I do the patination and this sometimes comes off happily, though sometimes you can’t repeat what you’ve done other times. The mixture of bronze may be different, the temperature to which you heat the bronze before put the acid on to it may be different. It is a very exciting but tricky and uncertain thing, this patination of bronze.12

According to Summers Moore did not regard the difficultly of replicating patinas as a problem. Moreover, she suggested that ‘a variation in colour within the edition also represented an element of choice for the potential client’.13 Although the dark brown-black base colour of Tate’s Falling Warrior is similar to the cast held in the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., a golden-brown patina has been applied to the high points of the Tate’s version to give a polished effect. Tate’s example, which has rarely been exhibited outdoors, has also been treated with a green patina, which gives the impression of natural weathering. However, this artificial effect contrasts sharply with the vivid sea-green patina of the cast displayed outside at Clare College, Cambridge, which has developed over time.

A cast of Falling Warrior was first exhibited in June 1958 at Marlborough Fine Art in London in an exhibition titled Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Masters. It was the first time Moore had exhibited at this commercial gallery but a month later he joined its stable of artists, which included Graham Sutherland and Francis Bacon. An unnamed critic reviewed the exhibition for the Times and under the banner ‘Mr. Moore’s New Sculpture: A Warrior To Be Proud Of’, noted that although the pose of the sculpture was akin to Moore’s regular subject of the reclining figure, in this instance ‘the whole open and vulnerable length of the body hangs suspended along the ground in the second before crumpling in ignominy and defeat’.14 Similarly, in his review of the exhibition, critic Alan Bowness wrote that ‘the outstanding contribution ... is that of Henry Moore the only English artist to be found in the Marlborough pantheon. He shows four bronzes, all on the Warrior theme. In the most important, the Falling Warrior of 1956–57, Mr. Moore makes a partial return to the reclining figure to create an image of impressive power, and beauty’.15 It is perhaps indicative of Moore’s acclaim at this time that discussion of this single sculpture dominated a review of an exhibition that also included work by Georges Braque, Edvard Munch, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso and Paul Klee.

Although the exhibition at Marlborough Fine Art was not referred to, in July 1958 the critic David Sylvester also singled out Falling Warrior for attention in an article published in the Listener. Under the title ‘A New Bronze by Henry Moore’ Sylvester observed that Falling Warrior marked a significant sea change in Moore’s approach to movement and the expression of muscular energy. Whereas earlier female reclining figures, he suggested, had been self-contained, serene and immovable, reminiscent of mountainous landscapes, ‘“Falling Warrior” is a complete break with all this. It is a convulsive work, in which energy is straining to break through’.16 Sylvester noted that the sculpture was at first disturbing because it was neither completely naturalistic nor totally abstract, but combined both modes of depiction. He went on to suggest that while the marriage of these two opposing forms of representation would usually result in an unsuccessful artwork, in Falling Warrior Moore used this duality to emphasise the tactile, muscular expression of the sculpture. By enlarging and distorting the belly and buttocks extra weight is given, while the thinness of the arms serves to emphasise the brittleness of bone. Meanwhile the naturalistic elements embedded the figure in the realm of the real. Sylvester proposed that the sculpture is best understood in terms of:

the experience within our own body of muscular stresses and strains ... So that, as we stand there and look at it we feel a dislocation in our torsos, we feel our backs hit the ground, our legs thrown helplessly in the air. The empathy we suffer is violent, convulsive, and seems to strain our muscles to the utmost limit.17

Falling Warrior is one of only six large-scale male forms made by Moore. Three of these male figures exist within groups: Family Group 1949 (Tate N06004), King and Queen 1952–3 (Tate T00228) and Harlow Family Group 1954–5 (Harlow Council). The remaining three are warriors: Warrior with Shield 1953–4 (a cast of which is at Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery); Falling Warrior 1956–7; and Goslar Warrior 1973–4 (Park Hinter der Kaiserpfalz, Goslar).

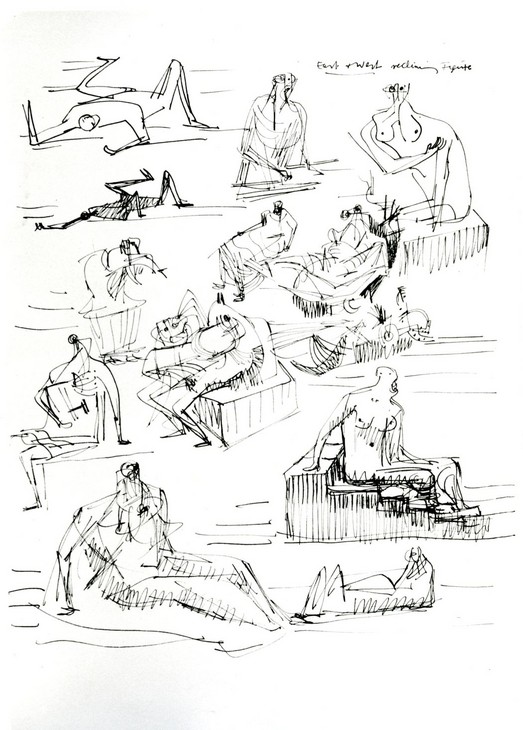

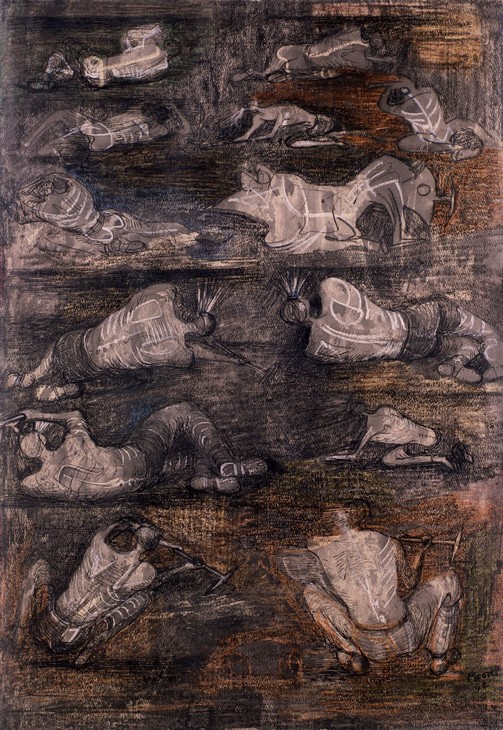

At the time Falling Warrior was created, Moore rarely made preparatory drawings for specific sculptures, preferring instead to sketch general ideas and work directly in plaster, utilising his accumulated knowledge of bodily forms to make preparatory three-dimensional maquettes. Nonetheless, it is possible to identify drawings that illuminate the evolution of Moore’s warrior sculptures. In particular, a sketch titled Figure Studies 1955–6 (fig.8) contains two pen and ink drawings each depicting a supine figure. With their raised arms and bent knees, the two sketches not only demonstrate that Moore was thinking about the prostrate figure in the mid-1950s, but also recall his earlier war-time drawings.

Henry Moore

Figure Studies 1955–6

Pen and ink on paper

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Figure Studies 1955–6

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Sleeping Positions 1941

Graphite, wax crayon, pen, ink and watercolour wash on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Sleeping Positions 1941

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

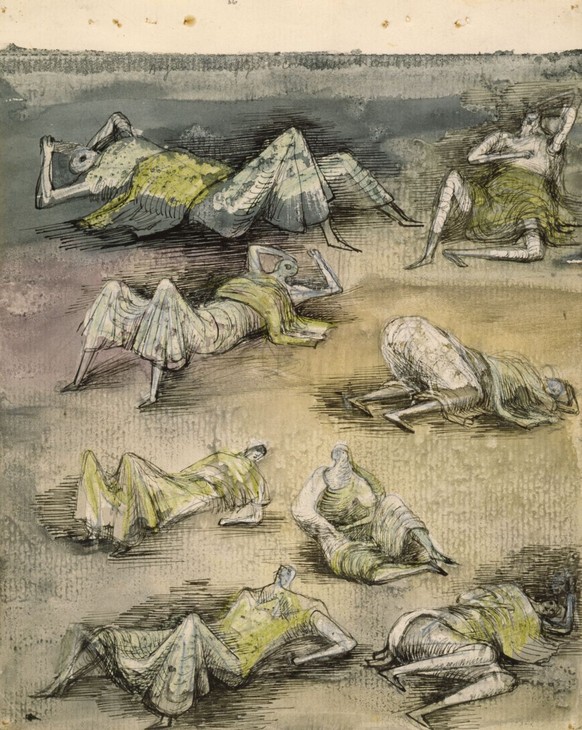

Sleeping Positions 1941 (fig.9) was drawn during the Second World War while Moore was working as an Official War Artist. It is part of his series of Shelter Drawings commissioned by the War Artists Committee, and depicts people – predominantly mothers and children – taking refuge from German aerial bombardment in the tunnels of the London Underground. However, the drawing differs from Moore’s other Shelter Drawings in which sleeping bodies are depicted tightly packed within the claustrophobic spaces. Presented in what appears to be an outside landscape, Sleeping Positions features eight lying figures, in various poses, each with different limbs covered and uncovered with blankets and illustrates how Moore was developing his repertoire of prostrate bodies. While the figure in the lower left of the page is presented with breasts, the other figures appear not to be gender specific. According to the art historian Frances Carey, the angular, twisted figures found in Sleeping Positions reappear in the later drawing Death of the Suitors 1944, itself a recognised precursor to Moore’s warrior series.18

Following the critical success of Moore’s Shelter Drawings, the critic Herbert Read suggested to the artist that he undertake a second commission from the War Artists Committee, this time depicting ‘Britain’s Army Underground’, the coal miners who ensured the regular supply of fuel for the nation during the Second World War. In 1947 Moore reflected that:

It was difficult, but something I am glad to have done. I have never willingly drawn male figures before – only as a student in college. Everything I had willingly drawn was female. But here, through these coal-mining drawings, I discovered the male figure and the qualities of the figure in action. As a sculptor I had previously believed only in static forms, that is forms in repose.19

In his coal mining drawings Moore undertook his first sustained examination of the male figure and became aware of the aesthetic and symbolic possibilities it presented, with particular regard for the figure in movement. The figure second from bottom on the left side of Miners at Work 1942 (fig.10) might be regarded as a graphic precursor to Moore’s sculpture: this figure is lying on his side, with his right arm lifted above his head. His twisted and curved body is tucked into a compact space and looking upwards he seems to be conscious that the roof could collapse. Kenneth Clark, who was Director of the National Gallery when he appointed Moore as an Official War Artist, later reflected that ‘such a figure as the fallen warrior would not have come into existence without the drawings of miners working on their backs’.20

Henry Moore

Miners at Work 1942

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink on paper

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Rodney Todd-White & Son, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Miners at Work 1942

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Rodney Todd-White & Son, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

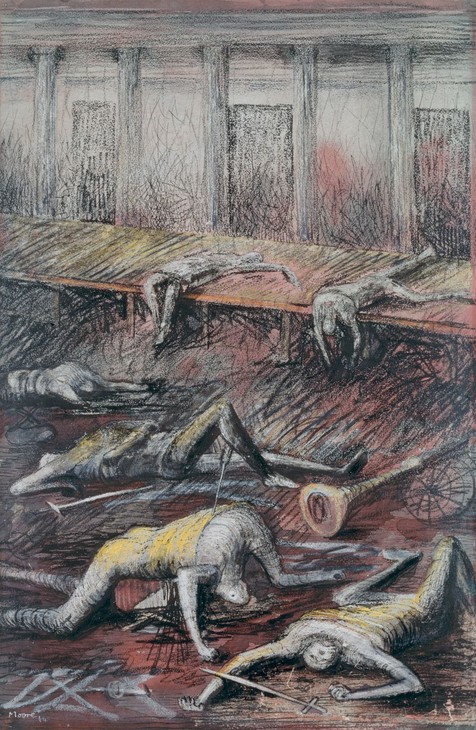

Henry Moore

The Death of the Suitors 1944

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink, brush and ink on paper

Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

The Death of the Suitors 1944

Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s The Death of the Suitors 1944 (fig.11) was one of a series of drawings created to illustrate Edward Sackville-West’s play The Rescue. The play was based on Homer’s Odyssey and Moore’s image depicts the aftermath of Odysseus’s rampage when, on returning home after fighting in the ten-year Trojan War, he kills the 108 suitors courting his wife Penelope. In 1970 the art critic Robert Melville regarded the male suitors in the drawing as studies for sculptures, suggesting that the violent scene ‘presents a fascinating spectacle of terracottas dying in a blood-red room’.21 Between 1949 and 1950 Moore also worked on lithographs for André Gide’s translation of Goethe’s Prometheus, itself based on Aeschylus’s ancient tragedy Prometheus Bound.22 The curator David Mitchinson has remarked that in these lithographs, as in The Death of the Suitors, ‘male flesh is perceived as being just as vulnerable as female’.23

The injured or traumatised male body was an infrequent but recurring subject in Moore’s work. Following his drawings of sleeping and dying figures of the 1940s, the painted plaster sculpture Reclining Warrior 1953 (fig.12), which was also cast in bronze, signals the start of Moore’s engagement with the male warrior subject in three-dimensional form. In 1955 Moore explained:

The idea for The Warrior came to me at the end of 1952 or very early in 1953. It was evolved from a pebble I found on the seashore in the summer of 1952, and which reminded me of the stump of a leg, amputated at the hip. Just as Leonardo says somewhere in his notebooks that a painter can find a battle scene in the lichen marks on a wall, so this gave me the start of The Warrior idea. First I added the body, leg and one arm and it became a wounded warrior, but first the figure was reclining.24

Moore then amended the orientation of Reclining Warrior, changing it from a horizontal to a seated position. In Moore’s opinion this amendment, with the addition of a shield, changed the sculpture ‘from an inactive pose into a figure which, though wounded, is still defiant’.25 This new version, Warrior with Shield 1953–4 (fig.13), was an exciting departure for Moore, who explained: ‘This sculpture is the first single and separate male figure that I have done in sculpture and carrying it out in its final large scale was almost like the discovery of a new subject matter; the bony, edgy, tense forms were a great excitement to make’.26

Henry Moore

Reclining Warrior 1953

Painted plaster

90 x 197 x 95 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Reclining Warrior 1953

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Warrior with Shield 1953–4

Bronze on wood plinth

1530 x 660 x 830 mm

Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Warrior with Shield 1953–4

Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In late February 1951 Moore made his first and only visit to Greece to attend the opening of his solo exhibition at the Zappeion Gallery in Athens. Although as a student Moore had rejected classical Greek sculpture and the traditional aesthetic doctrines that he then believed it stood for, he was nonetheless excited by the prospect of visiting the country’s ancient sites. At the age of fifty-two, Moore was struck by the light of Greece and the theatricality of its ancient monuments. He wrote to Kenneth Clark stating, ‘the Acropolis is wonderful – more marvellous than ever I imagined – The Parthenon against a blue sky – the sunlight + the scale it gets against the distant mountains can’t be given by any photograph – It’s the greatest thrill I’ve ever had’.27 The trip had a profound effect on him and in an interview of 1961 Moore recalled:

Mycenae had a tremendous impact. I felt that I understood Greek tragedy and – well the whole idea of Greece – much, much more completely than ever before. And Delphi, though I did find it had a slight tough of theatricality, as if eagles were flying round to order, and Olympia, with the idyllic sense of lovely living that you get there, and of course the whole of the Acropolis. That too had something I hadn’t at all foreseen.28

Moore also acknowledged that ‘I think The Warrior [with Shield] has some Greek influence, not consciously wished for but perhaps the result of my visit to Athens and other parts of Greece in 1951’.29 While Moore was circumspect about the direct impact of the visit on his work, Herbert Read was more assertive. Of Warrior with Shield he stated ‘there is a distinct Hellenic note, and it is the direct result of a visit to Greece which the sculptor made in 1951’.30 Moore’s choice of subjects in the 1950s – draped reclining women and warriors with shields – are certainly variants of those found in ancient Greek art, prompting art historian Roger Cardinal to describe them as ‘a sequence of works of a decidedly Greek tinge’.31 That Moore’s warriors of the 1950s are armed with a curved shield places them beyond or outside of the contemporary moment in which they were made; the shield, with the titular use of the term ‘warrior’ rather than ‘soldier’ suggests that the figures belong to the past. The scholar Will Grohmann also identified the origins for Moore’s series of warriors – Warrior with Shield, Falling Warrior and Maquette for Fallen Warrior – as stemming from his interest in classical Greek sculpture and mythology.32 He argued that the three-dimensional warriors may have developed from Moore’s engagement, albeit indirectly, with the texts of Homer and Aeschylus. For example, Grohmann described Warrior with Shield thus: ‘He is only a warrior, the prototype of the warrior, who has been defeated and mutilated in a murderous battle such as Homer sings of, who has lost his left arm and left leg and right foot, who has no weapon left but his shield, behind which he hides the remnant of his pitiable existence’.33 Following Grohmann’s interpretation, Cardinal suggested that it was Homer’s Iliad, rather than his Odyssey, which gave rise to Moore’s warrior imagery. Moore is known to have read and appreciated the Iliad with its accounts of ‘brave swordsmen succumbing to horrendous battle-wounds’.34 Grohmann concluded that ‘although there is nothing epic in the Falling Warrior, it contains the essence of the Homeric tale’.35

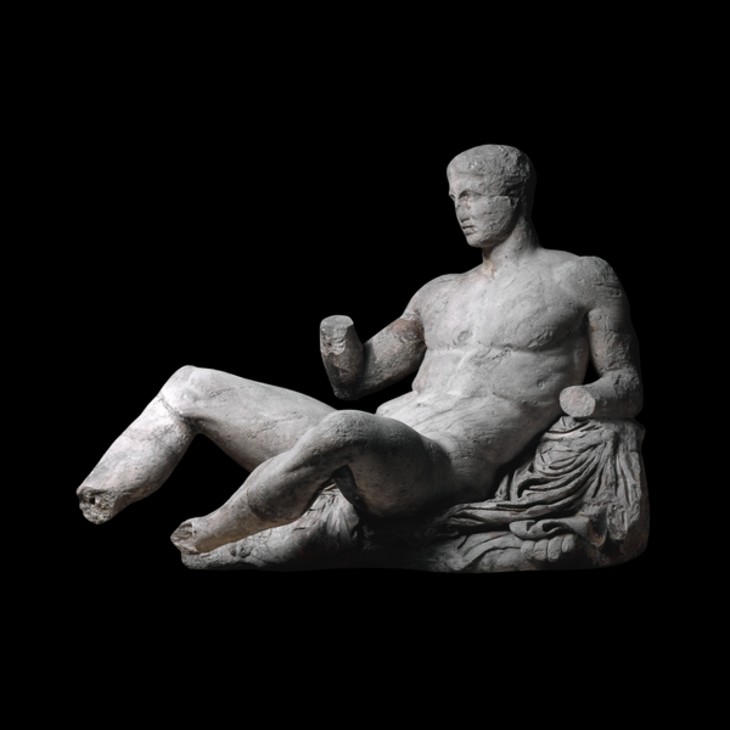

Fallen Warrior from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia c.490–480 BC

Glyptothek, Munich

Fig.14

Fallen Warrior from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia c.490–480 BC

Glyptothek, Munich

Figure of Dionysos from the east pediment of the Parthenon c.438–432 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.15

Figure of Dionysos from the east pediment of the Parthenon c.438–432 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

The sculptor who did this had a thorough understanding of the human figure, and shows so realistically the differences between the slackness of flesh and the hardness of the bone beneath it. I knew, as a young sculptor, that I had to learn all I could about the human figure, but I rather took the Greeks for granted and didn’t realise till much later how deep was their observation of human form. But this piece always attracted me, perhaps because of my interest in reclining figures.38

Cardinal suggested that the broken and fragmentary nature of the Greek examples in the British Museum and elsewhere was a particular inspiration to Moore. As demonstrated in the incomplete bodies of Reclining Warrior and Warrior with Shield ‘fragmentariness is itself an integral part of Moore’s creative vocabulary’.39 This damage to the body may have resonated with Moore when making his wounded warriors.

Considerations of Moore’s warrior sculptures of the 1950s in relation to his interest in classical sculpture and his 1951 trip to Greece have dominated critical discussions of these works. Such was Grohmann’s conviction that Moore’s Falling Warrior and the two other warrior sculptures were based on Greek sculptural traditions that in 1960 he refuted alternative visual references for these works – principally Moore’s experiences of war. Grohmann stated that Moore’s decision to create a series of warriors in the 1950s ‘cannot be explained by his war experience in London or the re-awakening of dreamlike memories of the First World War. It is certainly not the remoteness in time that makes this unlikely, but the figure of the “Warrior” itself, which has nothing to do with the anonymous, technological mass slaughter’.40

However, in 1955 Moore noted in relation to Warrior with Shield that ‘The figure may be emotionally connected (as one critic has suggested) with one’s feelings and thoughts about England during the crucial and early part of the last war. The position of the shield and its angle gives protection from above’.41 In 1970 the critic Robert Melville stated that Moore’s warrior theme ‘discloses an overt concern with the miseries of war’.42 This interpretation was echoed by art historian Christa Lichtenstern in 2008 who suggested that not only can the warrior subject be directly linked to slaughtered soldiers of the Second World War, but that Moore’s reference to the shield giving ‘protection from above’ alluded to the aerial bombardments suffered by cities including Coventry, Dresden, and Hiroshima. The composition of Falling Warrior similarly suggests an attack from above. Given that Moore’s supine warriors may have originated from his Shelter Drawings and those made for Edward Sackville-West’s The Rescue, it may be possible to view Moore’s warriors of the 1950s as extensions of and developments on his war-time imagery. Tate curator Chris Stephens has also suggested that Moore’s depiction of a falling soldier may have some relation to Robert Capa’s famous photograph Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death, Cerro Muriano, September 5, 1936 1936, first published in September 1936 in the French magazine Vu.43 It is known that Moore was sympathetic to the loyalist cause during the Spanish Civil War and it is likely that he knew of the image by the time he was working on Falling Warrior.44

In 1979 the filmmaker and writer John Read also found meaning for Falling Warrior in the Second World War and its aftermath. But rather than simply identifying the source of Moore’s imagery as stemming from his accumulated memories of war, Read suggested that Falling Warrior was also a comment on war. For Read the sculpture

can be made to correspond to a development in public feeling. It represents a complete reversal of the Greek ideal of martial virility and manhood. This man is no longer a hero. The sculpture bears an aura of pathos. There was, at least in Western culture, a profound revulsion against the military spirit and the futility of battle. In England this general sense of disillusionment was forcefully expressed in John Osborne’s play, Look Back in Anger. There were no proud causes left worth dying for.45

In a television programme titled England’s Henry Moore, first broadcast on Channel 4 on 21 September 1988, the Marxist literary critic and filmmaker Anthony Barnett proposed that many of the subjects and forms of Moore’s work may be attributed to his experiences during the First World War. Moore served as a gunner in the battle of Cambrai in late 1917; he was one of fifty-two survivors from his battalion of 400. During the attack Moore suffered gas poisoning and was hospitalised for three months. Obliquely referencing these experiences, in 1974 Kenneth Clark wrote that ‘the deep, disturbing well from which emerged his finest drawings and sculpture was never referred to and no one meeting him could have guessed at its existence’.46 Barnett, and subsequently the curators Jeremy Lewison and Chris Stephens, noted this aporia, suggesting that Moore’s memories of warfare and the sight of fallen, mutilated bodies permeated much of his work.47

Moore rarely explained his work with reference to contemporary events, preferring instead for sculptures such as Falling Warrior to stand as ahistorical symbols of and for a shared human condition. According to David Mitchinson:

Moore’s treatment of male subjects followed a clear pattern. In sculpture, as in his drawings and lithographs, they were never aggressive, militaristic, or bombastic ... All three of Moore’s warriors have shields, a classic item of defence, but no weapons of attack such as swords or spears. The shields when viewed as a traditional form of protection can be compared to the helmets in the helmet heads, or the exterior elements of the internal/external forms – hard defensive barriers safeguarding what lies beneath.48

In light of Mitchinson’s observations, Falling Warrior may be regarded not as an updated reworking of a classical subject, or a representation of the suffering caused by the Second World War, but rather as a more generalised depiction and reminder of the fragility of human life. In 1977 the compiler of Moore’s catalogue raisonné, Alan Bowness, observed that ‘the extraordinary impact of the Falling Warrior of 1956–7 ... derives from the half-conscious connection we immediately make between his fall and the idea of being ourselves in the same situation’.49 Moore’s recognition that tragedy could befall anyone at any time was perhaps reinforced during his visit to the archaeological site of Pompeii in 1954. Here Moore witnessed the consequences of a natural catastrophe – the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 – which buried the Roman town in volcanic ash. During his visit Moore was particularly intrigued by the plaster casts of preserved corpses lying on the ground, which he photographed from various angles (fig.16). Caught at the moment of their death these casts show the vulnerability of the body and Falling Warrior recalls the poses of these tragic figures.

Plaster cast corpse at Pompeii 1954

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore

Fig.16

Plaster cast corpse at Pompeii 1954

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore

Auguste Rodin

The Martyr 1899, cast 1917

Bronze

420 x 1520 x 1005 mm

Musée Rodin, Paris

Fig.17

Auguste Rodin

The Martyr 1899, cast 1917

Musée Rodin, Paris

In discussions of Falling Warrior very few commentators have deviated from the triumvirate of Moore’s interest in classical Greek sculpture and mythology, the memory of war, and the fragility of humanity. However, in 1968 the critic John Russell proposed an additional source and interpretation. He suggested that ‘The Falling Warrior adopts ... a pose that in another context might signify the extremes of sexual fulfillment: and the fulfillment, what is more, of a beautiful woman. This element of sexual ambiguity heightens the strangeness [of the sculpture] which does not, in any case, have anything to do with Greece. Moore here seems to be close to Rodin’.50 In the 1968 edition of Russell’s book a photograph of Falling Warrior is positioned opposite an image of Auguste Rodin’s The Martyr 1899 (fig.17).51 Rodin’s sculpture presents a bony, awkward, female figure lying on her left side, with her left arm falling limply off the edge of the base on which the sculpture is positioned. The figure’s right leg and left foot are suspended in the air, as if caught in the act of falling. The Martyr has been interpreted as being symbolic of the agony and ecstasy of love, as though wounded by love but nonetheless sexually fulfilled.52 The formal similarities between Falling Warrior and Rodin’s The Martyr probably encouraged Russell’s interpretation of Moore’s sculpture, despite and because Moore included a penis in his figurative representation. As art historian Norbert Lynton has observed, Moore generally ‘eschewed sexual motifs in his sculpture’ and sought to avoid ‘exciting thoughts of sexual activity or potentialities in his sculpture’.53 The inclusion of male genitals in Falling Warrior was unusual in Moore’s work and the presence of a penis may well have encouraged the sexualised readings he usually shunned.

Tate’s cast of Falling Warrior was exhibited in Moore’s mid-career exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, in 1960. The exhibition was generally well received in the press, with the critic David Thompson declaring in the Times that:

the quite extraordinary power and authority of the finest pieces in the exhibition exist in a sort of loneliness and silence, withdrawn from the madding crowd. This in itself is one of the many paradoxes inherent in the appeal of Moore’s art. As often as it retreats from immediate human contact and sympathy, it solicits them by its strong sense of pathos.54

Although by the time of the exhibition Moore was recognised as one of Britain’s foremost artists, responses to the show also revealed disenchantment with Moore’s aspirations to convey universal truths about humanity. In his review of the exhibition published in Art International, the critic Lawrence Alloway suggested that the sculptures on display at the Whitechapel were ‘an awkward repertoire of heroic gestures’.55 While Alloway noted that Moore’s earlier carvings developed the unique qualities of his raw materials, at the Whitechapel, ‘the human attributes of pose or anatomical detail seem to grow neither out of a full mastery of the human body nor out of an intimate response to the material itself’.56 Alloway then went on to compare the exhibition to the visual spectacle of the opera, where the nuances of each individual character is sublimated into the whole: ‘Similarly with Moore’s figures of the past decade: their gestures and poses seem less than heroic within the heroic massing. (One is somewhat reminded of the helplessness of di Chirico’s gladiators in his arena paintings of the 20s)’.57 Alloway proposed that the problem of Moore’s work, and the reason that his attempted depiction of heroism failed in works such as Falling Warrior, was that it displayed a conscious attempt to convey a comprehensive humanist sentiment. ‘Obviously out of the highest motives,’ Alloway remarked, ‘Moore is hoping to give his public sculptures a worthy message, a stirring content’. Yet the critic suggested that it was impossible to speak of universals, that a person can only speak of their own time and place: ‘Moore seems dissatisfied with what he can reach from his own situation. As a result all he offers, despite his ambition, is a sculpture of empty Virtues’.58

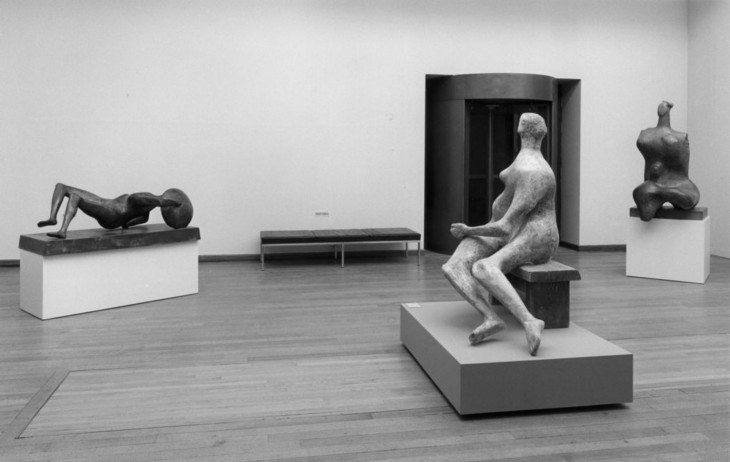

Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60 on display in the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery in 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.18

Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60 on display in the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery in 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Falling Warrior exists in an edition of ten plus one artist’s copy. Other examples of the sculpture are held in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago; the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich; Clare College, Cambridge; the Hakone Open Air Museum, Hakone; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.; Huddersfield Art Gallery (Kirklees Metropolitan Council); and the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. The remaining casts are believed to be held in private collections.

Alice Correia

February 2013

Notes

See John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.125–6, and John Read, Portrait of an Artist: Henry Moore, London 1979, p.112.

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2278 Falling Warrior 1956–7’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.123–4.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, p.113, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.226.

A photograph captioned ‘The finished Falling Warrior, 1956–57’ showing this full-size version of the sculpture is also included in Read 1979, p.114.

For a video explaining the lost wax process see http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/s/sculpture-techniques/ , accessed 23 January 2014.

Julie Summers, ‘Gilding the Lily: The Patination of Henry Moore’s Bronze Sculptures’, in Jackie Heuman (ed.) From Marble to Chocolate: The Conservation of Modern Sculpture, London 1995, p.145.

Frances Carey, ‘Sleeping Positions 1941’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.191.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeny, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, pp.184–5, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.266.

See David Mitchinson (ed.), Moore and Mythology, exhibition catalogue, The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green 2007.

Henry Moore cited in John and Vera Russell, ‘Conversations with Henry Moore’, Sunday Times, 24 December 1961, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.69.

Herbert Read, ‘Introduction’, in Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1955, 1955, 2nd edn, London 1965, pp.x–xi.

Roger Cardinal, ‘Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece’, in Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, p.30.

See Henry Moore, letter to Raymond Coxon and Edna Ginesi [Peacham & Gin], [August/September 1936], Tate Archive.

See Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007, and Chris Stephens, ‘Anything But Gentle: Henry Moore – Modern Sculptor’, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, pp.12–17.

David Mitchinson, ‘Introduction: War and Utility’, Henry Moore: War and Utility, exhibition catalogue, Imperial War Museum, London 2006, p.16.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- 'I tried to push him down the stairs': John Berger and Henry Moore in Parallel Tom Overton

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

- ‘A sincere academic modern’: Clement Greenberg on Henry Moore Courtney J. Martin

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Henry MooreLetter to Raymond Coxon and Edna Ginesi (Peacham & Gin) Late August/ early September 1936Letter

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, February 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www