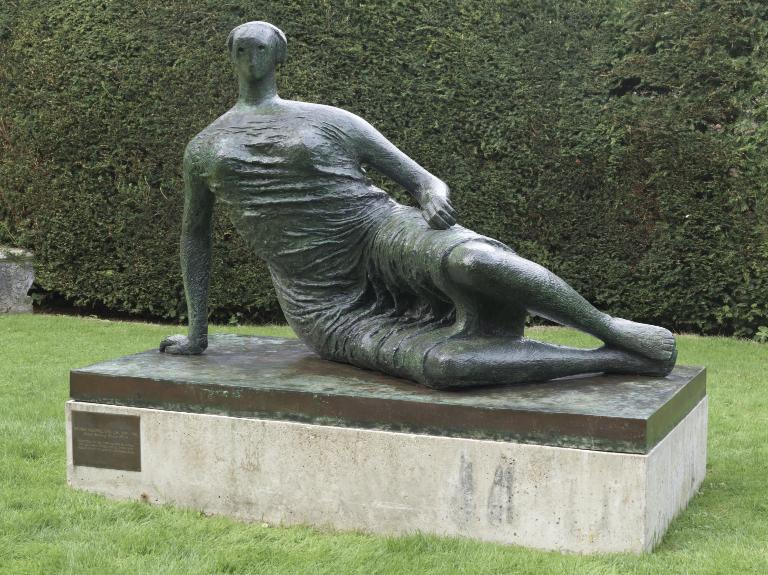

Henry Moore OM, CH Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown

Image 1 of 17

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Draped Reclining Woman 1957-8, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Draped Reclining Woman

1957-8, cast date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Draped Reclining Woman is one of a number of large-scale sculptures by Moore of women wearing drapery that date from the 1950s. The influence of classical Greek art on Moore’s work at this time is demonstrated by the form and pose of the figure, which has been interpreted variously as a representation of the universal ‘earth mother’, and as a monument to the civil aspirations and social reforms of the post-war period.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Draped Reclining Woman

1957–8, cast date unknown

Bronze

1346 x 2083 x 914 mm

Presented by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler 1974, accessioned 1994

Number 2 in an edition of 6 plus 1 artist’s copy

T06825

Draped Reclining Woman

1957–8, cast date unknown

Bronze

1346 x 2083 x 914 mm

Presented by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler 1974, accessioned 1994

Number 2 in an edition of 6 plus 1 artist’s copy

T06825

Ownership history

Acquired directly from the artist by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler in c.1958, by whom presented to Tate in 1974, accessioned 1994.

Exhibition history

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972 (?another cast exhibited no.79).

2007–8

Moore at Kew, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, September 2007–March 2008, no number.

References

1959

Documenta Katalog, exhibition catalogue, Documenta 2, Kassel 1959, pp.58–9 (another cast reproduced on back cover).

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Gallery, London 1960 (?another cast reproduced no.61).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, reproduced pls.207, 209.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968 (?another cast reproduced pp.296–7, 330–1).

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968 (another cast reproduced pp.172, 174).

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972, reproduced pp.152–3.

1976

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1976 (another cast reproduced pp.130–3).

1979

Alan Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, p.155 (plaster original reproduced pl.129).

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Sculpture 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, p.35, no.431 (?another cast reproduced pls.50b, 60–2).

1987

Alan Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, pp.178–80 (plaster original reproduced no.129).

2000

Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, pp.28–9.

2004

Giorgia Bottinelli, ‘Henry Moore’, in Jennifer Mundy (ed.), Cubism and its Legacy: The Gift of Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2004, pp.82–7, reproduced p.87.

2006

Christopher Marshall, ‘Between Beauty and Power: Henry Moore’s Draped Seated Woman as an Emblem of the National Gallery of Victoria’s Modernity 1959–68’, Art Bulletin of Victoria, vol.46, 2006, pp.37–49.

2011

Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011 (full-size plaster reproduced pp.88–9).

Technique and condition

This bronze sculpture depicts a woman reclining on a bronze rectangular base. She leans on her right hip while her legs, which are bent at the knee, extend to her left. Her head faces forward and her eyes are represented by deeply inset holes, whereas the nose and mouth are barely visible as small projections on an otherwise planar surface. Much of her weight is supported on her almost vertical right arm, while her left hand rests gently on her left hip. She wears a robe that is draped over her body in deep folds and wrinkles. The sculpture is coloured a deep variegated green.

The mould from which this sculpture was cast in bronze would have been taken from a full-size model made of plaster. To make a plaster sculpture of this size Moore would have first built an armature, possibly using a combination of wood, chicken wire and scrim, which served as a supportive skeleton onto which successive layers of wet plaster were applied to slowly build up the form. Moore used a number of tools to model the surface of his plaster sculptures, and in the case of this work differentiated between the textures of flesh, hair and fabric using different techniques. For example, the arms, legs and neck are marked with numerous fine striations, perhaps made using a combination of chisels, gouges and graters, whereas the figure’s hair is deeply chiseled (fig.1). Moore probably created the folds on the woman’s dress by draping fabric soaked in wet plaster over the form of the figure. He could then arrange the fabric before it set and build plaster over it until he was satisfied with how it looked. Spatula marks testifying to this process can be seen on the front of the figure (fig.2), while the fabric depicted across the woman’s back has a smoother surface.

Detail of hair and neck of Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (rear view)

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of hair and neck of Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (rear view)

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of fabric folds on front of Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of fabric folds on front of Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Plasters of this size would usually be cut into sections at the foundry and individual moulds would be taken of each part to make the casting process more manageable. The cast bronze sections would then be welded together to make the completed sculpture. Weld joins would be carefully filed down and textured with a series of special punches to blend with the surrounding area. This process is called chasing and is the method by which repairs and joins on a bronze are disguised after casting. Draped Reclining Woman was cast at the Noack Foundry in West Berlin in an edition of six plus one artist’s copy. It is not possible to determine exactly which casting method was used to fabricate this sculpture, but the high level of surface detail suggests that it was cast using the lost wax process.

Apart from having been chased and cleaned no other post-cast finishing was undertaken on the sculpture. It was artificially patinated by applying chemical solutions to the bronze, either with or without heat, which reacted with the surface to form various coloured compounds. This sculpture has a deep variegated green patina with brown tints in the recesses. Bronzes displayed outdoors tend to develop a green patina due to chemical compounds in the atmosphere, so it is difficult to ascertain the original colour of this sculpture, although it is possible that it was brown with an overlying green patina that has intensified through exposure to the elements.

After it had been patinated this sculpture would have been given a coating of wax to protect it. Wax can be tinted to enhance the patina and close examination of the sculpture suggests that a brown wax has been used in the past. As part of Tate’s ongoing conservation programme for all its outdoor sculptures a clear conservation-grade wax is now applied on an annual basis. The bronze is also examined to check for any signs of degradation and its surface washed to remove bird lime and dirt. These measures help to ensure that it remains in good condition.

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

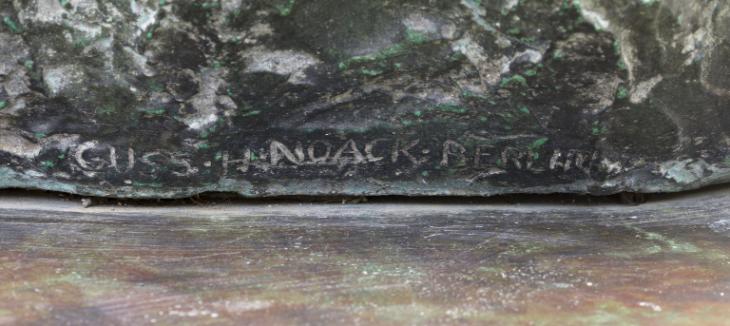

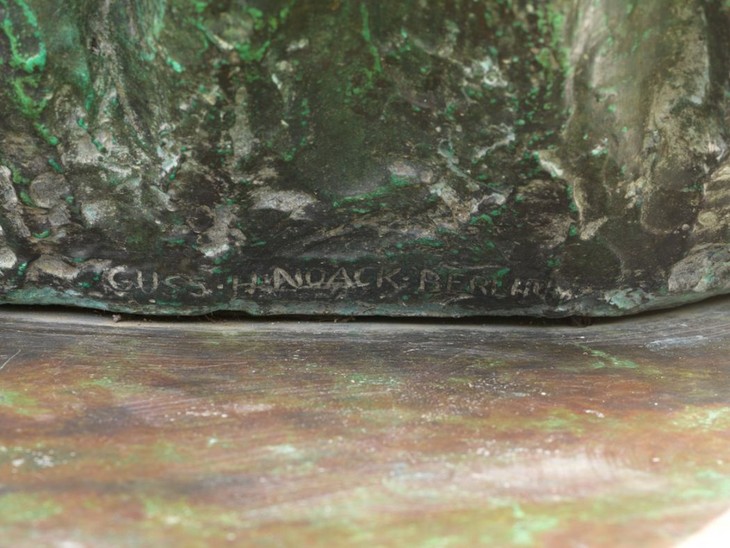

Detail of foundry stamp on Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of foundry stamp on Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The sculpture is signed ‘Moore 2/6’ at the rear, close to where it meets the base (fig.3) and has been inscribed with the foundry mark ‘GUSS.H.NOACK.BERLIN’ (fig.4) to the right of this. On each of the two long sides of the base are two large slot-headed screws set flush with the surface. These are inserted to cover threaded holes that can be used as attachment points to help install the bronze on its base using slings and lifting equipment. When on display at Glyndebourne the base rests on a low concrete plinth.

Lyndsey Morgan

January 2014

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', January 2014, in Alice Correia, ‘Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 is a larger than life-size bronze sculpture of a reclining female figure whose bulky torso sits upright, facing forwards, while her legs extend horizontally to her left (fig.1). The figure is proportioned irregularly, possessing a small head relative to the size of her body and unnaturally long legs. Much of her weight is placed on her almost vertical right arm, her buttocks and her right thigh, all of which rest on the base, while her left arm rests gently on top of her left thigh. The woman wears a sleeveless, knee length dress, which appears to cling to her body, creating crinkles and ripples across her chest while deeper grooves and ridges traverse her legs and dip between her thighs.

Detail of face of Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of face of Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of hair and neck of Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (rear view)

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of hair and neck of Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (rear view)

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

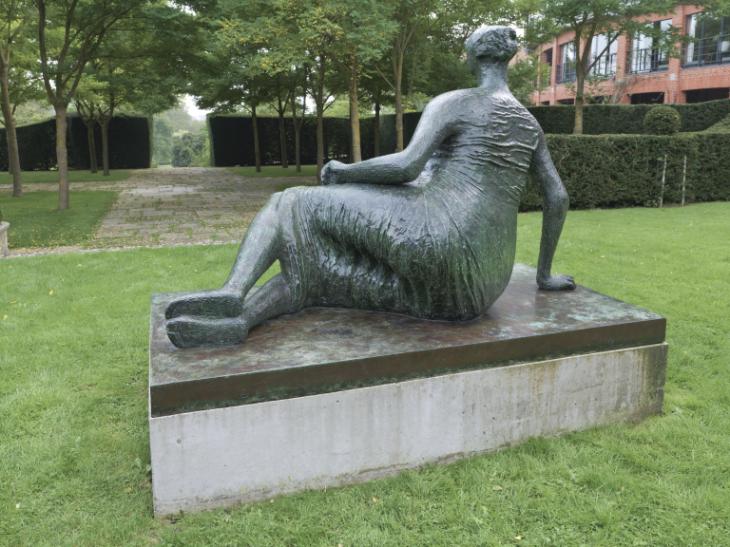

Two evenly spaced circular depressions on the figure’s face denote eyes, in between which a slight notch delineates the tip of her nose (fig.2). The figure has a high forehead and her hair has been rendered through a series of overlapping craggy masses at the rear of the head (fig.3). When seen from the rear it is evident that the woman has a very broad torso and large buttocks (fig.4). From this angle the shape of the right thigh can be seen beneath the fabric of the skirt, which has been pulled taught, indicating that the legs are slightly parted. Her bare knees, shins and feet are placed almost horizontally and there is a gap between her two calves. Her ankles have little definition and the inner edge of the left foot balances on top of the right (fig.5).

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (rear view)

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (rear view)

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (side view)

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (side view)

Tate T06825

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From plaster to bronze

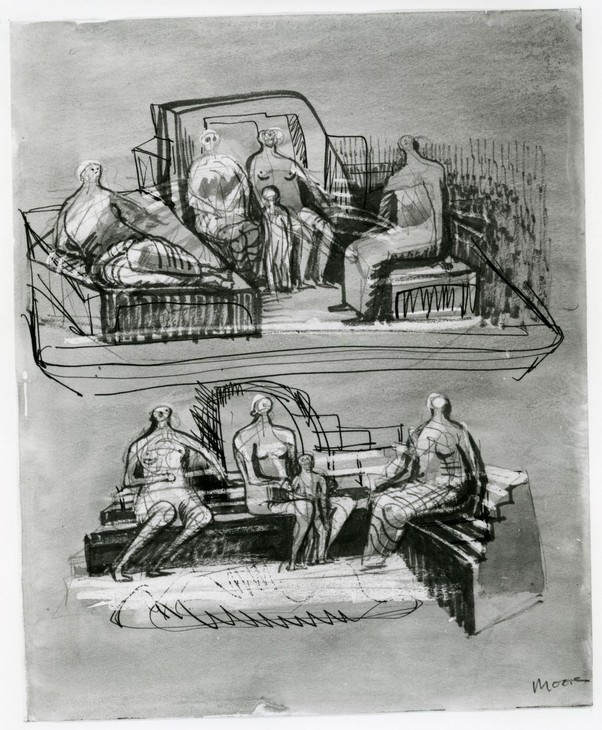

Henry Moore

Figures on Steps 1956

Graphite, wax crayon, watercolour wash, felt-tipped pen, pen and ink on paper

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Figures on Steps 1956

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Fragment Figure 1957

Plaster

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Fragment Figure 1957

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Having decided to proceed with the sculpture, Moore would then have created a plaster model at full size. Using the working model as a guide, an armature, probably made of wood and wire netting, was constructed, over which Moore and his assistants would have draped layers of scrim soaked in plaster. Scrim is a bandage-like fabric with a loose weave that allows plaster to soak into the layers easily. Once the plaster and scrim had hardened to form a shell, layers of thicker plaster could then be applied with trowels and spatulas until the sculpture started to gain mass and form. This work would have been carried out in the White Studio at Hoglands, or if the weather was fine, outside on the terrace. Moore would have allocated the bulk of this work to his studio assistants, who between 1957 and 1958 included Geoffrey Harris, Anthony Hatwell, Daryll Hill, Maurice Lowe and Stephen Rich.

After the final form had been arrived at Moore would have taken over and worked on the sculpture’s surface texture. Using an array of tools, including chisels, files and sandpaper, Moore could create different types of textures according to how wet or dry the plaster was. When asked by the critic David Sylvester in 1963 whether the surface textures of his sculptures were planned at the initial maquette stage, Moore replied:

No. No, the surface comes about from the way you do it. You can’t possibly imitate the surface on a six-inch maquette ... you foresee it a little bit, but you don’t foresee entirely because the doing of a thing always changes ... this business of surface and texture should be, in my opinion, the outcome of how you do a thing and what degree of refinement, of shape you want to get.3

In 1955 Moore discussed the ways in which he modelled drapery, explaining, ‘gradually I evolved a treatment that exploited the fluidity of plaster. The treatment of drapery in my stone carvings was a matter of large, simple creases and folds but the modelling technique enabled me to build up large forms with a host of small crinklings and rucklings of the fabric’.4 Cast directly from the plaster, the resulting bronze sculpture replicated these different surface textures accurately.

Once Moore was satisfied with the surface finish of the sculpture and was sure that he wanted to proceed with the casting process, the full-size plaster was sent to the Noack Foundry in West Berlin to be cast in bronze. Seven versions of Draped Reclining Woman exist, of which this is number two. The edition number and Moore’s signature can be found on the lower rear of the sculpture, as can the foundry stamp.

Technicians at the foundry would have cut the plaster sculpture into smaller pieces and then created moulds of each section from which the bronze parts could be cast. It is not known which technique was used to cast this sculpture, but the high level of surface detail on the bronze suggests that the lost wax method was used. Once all the pieces of the sculpture had been cast they were welded together and the casting seams ‘chased’ to render the joins as imperceptible as possible. The finished sculpture was then returned to Moore so that he could check the quality of casting and make decisions about the patina. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the bronze surface, although colours also develop naturally over time on bronze sculptures displayed outside. However, Moore preferred to patinate his sculptures himself to draw out or highlight individual forms. In 1963 he explained to Sylvester that ‘one tries with any patina to help the form of a sculpture rather than to obscure it’.5 Tate’s cast of Draped Reclining Woman has a dark underlying patina, with a mottled green sheen over the top.

Origins and contexts

Moore carved his first reclining figure around 1924, but took up the subject with greater seriousness in 1929 and it became his most frequently recurring subject. In 1947 Moore accounted for his preference for the reclining figure, stating:

There are three fundamental poses of the human figure. One is standing, the other is seated, and the third is lying down ... of the three poses, the reclining figure gives most freedom compositionally and spatially. The seated figure has to have something to sit on. You can’t free it from its pedestal. A reclining figure can recline on any surface. It is free and stable at the same time. It fits in with my belief that sculpture should be permanent, should last for eternity. Also, it has repose, it suits me – if you know what I mean.6

By choosing the subject of the reclining female figure for his sculptures, Moore was free to experiment with sculptural forms, both compositionally (in the position of the body and its limbs) and spatially (in the ways in which the figure’s limbs projected into space and interacted with spatial gaps). In addition to these perceived virtues, Moore also believed that because the subject of the reclining figure was known and understood, he was not tied to creating naturalistic artworks. On the subject of his reclining figures Moore was clear that he did not seek to imbue his sculptures with a specific meaning, but rather to use the motif as a starting-point for formal experiments:

I want to be quite free of having to find a ‘reason’ for doing the Reclining Figures, and freer still of having to find a ‘meaning’ for them. The vital thing for an artist is to have a subject that allows [him] to try out all kinds of formal ideas – things that he doesn’t yet know about for certain but wants to experiment with, as Cézanne did in this ‘Bathers’ series. In my case the reclining figure provides chances of that sort. The subject-matter is given. It’s settled for you, and you know it and like it, so that within it, within the subject that you’ve done a dozen times before, you are free to invent a completely new form-idea.7

Moore’s preference for bulky, weighty bodies, exemplified by Draped Reclining Woman, may have originated from his admiration for the large, fleshy women painted by Paul Cézanne (1839–1906): ‘not young girls but that wide, broad, mature woman. Matronly’.8 These ‘broad, mature’ women may in turn have reminded Moore of what the curator Alan Wilkinson described as one of his ‘earliest and most important tactile sensations ... rubbing his mother’s back with liniment, to ease the pain of her rheumatism’ as a young boy.9 While there is no reason to believe that Moore was directly representing his mother in this sculpture, his particular feeling for the form of broad bodily expanses may have been drawn from his childhood experiences.

In his analysis of Moore’s work the psychologist Erich Neumann related the maternal aspects of Moore’s large women to those of the archetypal ‘Great Mother’.10 Identifying the centrality of this archetype to ancient civilisations, Neumann described the Great Mother as a symbol of ‘nourishment, shelter and security’, and ‘the mistress of life and fertility’.11 Indeed, Neumann posited that as a fundamental trope of human consciousness the archetype, once sublimated, would soon return to prominence:

the sovereign power of motherhood determined the earliest phase of man’s development, and only later, with the growth of consciousness, was it superseded and overlaid by the significance of the father and the patriarchal values connected with the father archetype. Today a new shift of values is beginning, and with the gradual decay of the patriarchal canon we can discern a new emergence of the matriarchal world in the consciousness of Western man.12

Discussing Draped Reclining Woman, Neumann observed that ‘despite the looseness of the body and its easy repose, the sturdy legs, flexed up and lightly splayed, with the heavy loop of skirt hanging between them, suggest a mature woman, fecund, maternal, earthy – a fine breeder with nothing in the least girlish about her’.13

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3

Bronze

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jonty Wilde, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jonty Wilde, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

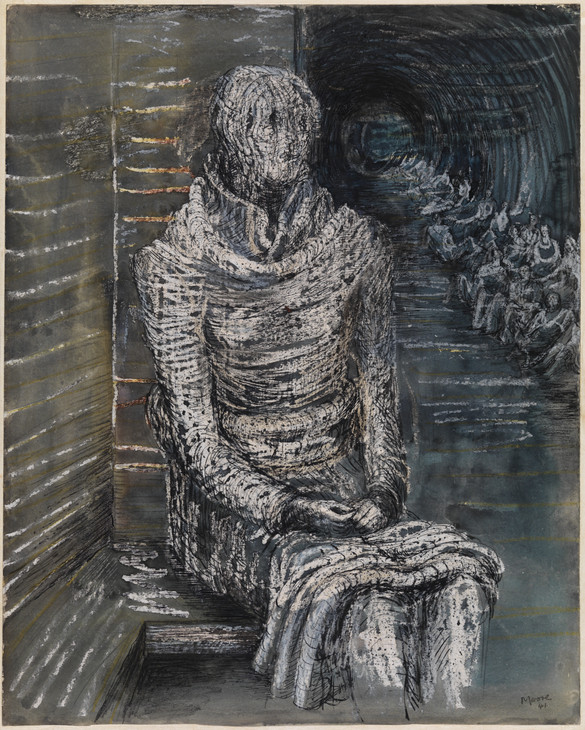

Drapery played a very important part in the shelter drawings I made in 1940 and 1941 and what I began to learn then about its function as form gave me the intention, sometime or other, to use drapery in sculpture in a more realistic way than I had ever tried to use it in my carved sculpture. And my first visit to Greece in 1951 perhaps helped to strengthen this intention ... Drapery can emphasise the tension in figure, for where the form pushes outwards, such as on the shoulders, the thighs, the breasts etc., it can be pulled tight across the form (almost like a bandage), and by contrast with the crumpled slackness of the drapery which lies between the salient points, the pressure from inside is intensified.

Drapery can also, by its direction over the form, make more obvious the section, that is, show shape. It need not be just a decorative addition, but can serve to stress the sculptural idea of the figure.

Also in my mind was to connect the contrast of the size of folds, here small, fine, and delicate, in other places big and heavy, with the form of mountains, which are the crinkled skin of earth.14

Drapery can also, by its direction over the form, make more obvious the section, that is, show shape. It need not be just a decorative addition, but can serve to stress the sculptural idea of the figure.

Also in my mind was to connect the contrast of the size of folds, here small, fine, and delicate, in other places big and heavy, with the form of mountains, which are the crinkled skin of earth.14

Moore was evidently keen to downplay the notion that his use of drapery was decorative, instead proposing that it had a formative role in the presentation of the sculpture in three dimensions. Drapery could convey tension and repose and it could both disguise and emphasise the mass and volume of a sculpture. That Moore described the act of pulling it ‘across the form’ suggests that he identified the relationship between the figure and the drapery in terms of the contrast between stillness and motion. As the critic Ionel Jianou noted of Moore’s draped figures in 1968, ‘the drapery contributes to the quivering life of the sculpture’.15

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Woman Seated in the Underground 1941

Gouache, ink, watercolour and crayon on paper

support: 483 x 381 mm

Tate N05707

Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee 1946

Fig.9

Henry Moore OM, CH

Woman Seated in the Underground 1941

Tate N05707

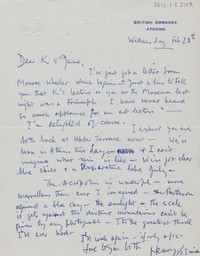

Moore also recognised the importance of his first and only visit to Greece in 1951 as a stimulus for his draped women. Moore travelled there in February 1951 to attend the opening of an exhibition of his work at the Zappeion Gallery, Athens, organised by the British Council, but also took the opportunity to visit the country’s museums and ancient sites. While in Athens he visited the National Museum at least four times and the National Gallery once, as well as the various ancient structures clustered at the top of the Acropolis. In 1960 Moore recounted that:

there was a period when I tried to avoid looking at Greek sculpture of any kind. And Renaissance. When I thought that the Greek and Renaissance were the enemy, and that one had to throw all that over and start again from the beginning of primitive art. It’s only perhaps in the last ten or fifteen years that I began to know how wonderful the Elgin Marbles are.17

Photographs of a Greek classical statue from the Nereid Monument (fig.10), dating from the fourth century BC, were reproduced in the 1981 publication Henry Moore at the British Museum. For this book Moore selected and discussed artworks from the British Museum’s collection that had influenced his work, and stated of the Greek sculpture:

The drapery here is so sensitively carved that it gives the impression of light, flimsy material, wet with spray, being blown against the body by the wind. It shows how drapery can reveal the form more effectively than if the figure were nude because it can emphasise the prominent parts of the body, and falls slackly into the hollows. This is something I learned when I came to do the Shelter drawings, in which all the figures are draped. Before then I avoided using drapery because I wanted to be absolutely explicit about shapes and forms. I so admire the Greek sculptor who had the vision and the ability to make of stone something so apparently flimsy as the drapery on this figure.18

For the critic John Russell, however, Moore’s 1954 statement in fact ‘disposes altogether ... the idea that the draped statues owe anything substantial to Greek art’.19 Highlighting the artist’s reference to the ‘crinkled skin of earth’, Russell proposed that Moore was associating the drapery, and by analogy the female figure, with the landscape and thus developing an area of enquiry that he had already explored in detail, particularly in his pre-war reclining figures. Elaborating on these parallels, Russell claimed that Moore used drapery,

To romantic ends that would have been incomprehensible to the Greeks. The ‘crinkled skin of the earth’ was not something that they would have thought of as a metaphor for the folds of costume, but it was one of the quintessential metaphors for emotional states in the England of the 1940s and 1950s. Look at John Piper or Geoffrey Grigson on the derivations of British Romantic painting and you will find, over and over again, typographical references of this sort: drapery, for Moore, was another way, and a new one, of mediating between landscape and the human body.20

Initial display and reception

A cast of Draped Reclining Woman was exhibited as part of Moore’s solo display at Documenta 2 – a major international exhibition in Kassel, Germany, in the summer of 1959 – and would have undoubtedly brought it to the attention of more critics and collectors. Reviewing the show, the critic for the Times wrote that Moore’s ‘huge lying and seated draped women – not yet exhibited in England – introduce a quality of intense pathos and sensibility into the monumental which renders them both distant and appealing. They are in many ways the high point of this exhaustive and sometimes exhausting display’.21

According to the art historian Christopher Marshall, the success of Moore’s monumental women was due to the way they answered ‘a deep-seated postwar need for an epic, modern, civic art that might help rebuild a shattered Europe through the reinforcement of universal humanist values that reconnected the individual to the landscape, both urban and natural’.22 Indeed, a central tenet of Erich Neumann’s thesis was that Moore’s turn to the archetypal ‘Great Mother’ was not simply a matter of personal choice, but rather an exemplary manifestation of a more widespread tendency of the post-war era, which sought alternatives to the patriarchal ideologies that led to the devastation of the Second World War.23

In 1960 another cast of Draped Reclining Woman was exhibited in Moore’s solo exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London. Curated by Bryan Robertson, the exhibition comprised sculptures made since 1950, and was Moore’s first major exhibition in London for five years. The exhibition was generally well received in the press, although critics were careful to note the divergent figurative and abstract styles on display. With regard to Draped Reclining Woman and Draped Seated Woman 1957 (Tate L01444), critics noted Moore’s debt to ancient Greek art and identified a sense of isolation in both works. The critic David Thompson asserted in the Times that Moore’s sculptures ‘exist in a sort of loneliness and silence, withdrawn from the madding crowd’.24 He concluded that ‘the massive, draped figures of seated women (1957–58) ... seem both calm and monumentally unrelaxed’.25 Writing in the Listener, Keith Sutton noted similarly that ‘the various seated and reclining goddesses are by nature indifferent to our presence, making no concessions to identification. They are as stoic as the river gods of Arcady: in their water-flowing draperies their attention is alerted by more primal echoes’.26

The Kahnweiler Gift

Draped Reclining Woman was presented to Tate by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler.27 In the 1950s and 1960s the Kahnweilers were among the few art collectors in the United Kingdom who actively supported the work of European modern artists and they amassed a large collection of paintings and sculptures by artists including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Fernand Léger. Partly as a result of their friendship with the Tate director Sir John Rothenstein and with his successor Sir Norman Reid they decided to leave their entire art collection to the gallery after their deaths. A Trust Deed was signed in 1974, immediately after which a group of works were passed over to Tate. Gustav died in 1989 and the remaining works, including Draped Reclining Woman, were accessioned into the Tate’s collection in 1994 following Elly’s death in 1991.

It is not known how or when the Kahnweilers first met Henry Moore, but they may have become familiar with his work in the late 1930s when Moore exhibited at the Mayor Gallery in London, one of the few commercial galleries that actively exhibited and supported the work of modern artists working in Britain and continental Europe. Nonetheless, by the 1950s the Kahnweilers, Moore and Moore’s wife Irina shared a warm friendship. As well as purchasing works by Moore for their own collection, Gustav acted occasionally as an agent in the sale of Moore’s sculptures. For example, in 1952 he negotiated the sale of Moore’s sculpture to the Kunstmuseum in Basel. The Kahnweilers acquired Draped Reclining Woman directly from Moore shortly after it was cast. An undated note written in Moore’s sales book records that the Kahnweilers were promised a cast as soon as one was available.28 The sculpture was displayed in the grounds of their home in Buckinghamshire until it entered Tate’s collection.

When he died Gustav left detailed instructions regarding the Tate’s gift, and following Elly’s death a total of fifty-five artworks entered the Tate’s collection, including works by Braque, Paul Klee, Henri Laurens, André Masson and Picasso. Along with Draped Reclining Woman, four other sculptures by Henry Moore were included in the Kahnweiler Gift: Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956 (Tate T06824), Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961 (Tate T06826), Maquette for Standing Figure 1950 (Tate T06827), and Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956 (Tate T06828).

One of the stipulations of the Kahnweiler Gift was that Draped Reclining Woman be placed on long-term long at Glyndebourne in East Sussex, where it would be seen by visitors to the famous opera festival that takes place there every year. During their lifetimes the Kahnweilers greatly enjoyed attending performances at Glyndebourne, but the terms of the agreement note that Tate may remove the sculpture should the quality of the opera programme fall below the standards the Kahnweilers had come to expect.

Other casts of Draped Reclining Woman are held in the collection of the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norwich; the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich; the Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart; and the Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena.29 Two casts are believed to be in private collections in the USA. The full-size plaster original is in the Henry Moore Sculpture Center, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Alice Correia

December 2013

Notes

Alan Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.179.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, broadcast BBC Radio, 14 July 1963, pp.8–9, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Henry Moore, ‘Sculpture in the Open Air: A Talk by Henry Moore on his Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites’, 1955, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.280.

Henry Moore cited in J.D. Morse, ‘Henry Moore Comes to America’, Magazine of Art, vol.40, no.3, March 1947, pp.97–101, reprinted in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.264.

Henry Moore cited in Hew Wheldon (ed.), Monitor: An Anthology, London 1962, pp.21–2, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.147.

Henry Moore quoted in Sculpture in the Open Air, exhibition catalogue, Holland Park, London 1954, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.280.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeney, Henry Moore, New York 1946, reprinted in James 1966, p.42.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in James 1966, pp.47–8.

Christopher Marshall, ‘Between Beauty and Power: Henry Moore’s Draped Seated Woman as an Emblem of the National Gallery of Victoria’s Modernity 1959–68’, Art Bulletin of Victoria, vol.46, 2006, p.41.

For a full account of the Kahnweiler Gift see Jennifer Mundy (ed.), Cubism and its Legacy: The Gift of Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2004.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and the Values of Business Alex J. Taylor

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore and the Welfare State Dawn Pereira

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

- ‘Worthy of the great tradition’: Kenneth Clark on Henry Moore Chris Stephens

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www