Henry Moore and the Values of Business

Alex J. Taylor

Moore was one of the most financially successful artists of the post-war era. This essay explores the strategies and contexts that sustained this worldwide commercial success.

As post-war art followed the path of capitalism, organising its production and distribution to suit the demands of a global market, its cultural values became increasingly linked to its status as a financial instrument. The rising value of modernist art became a leitmotif of public discussions about art from the late 1950s, and one in which the name of Henry Moore was omnipresent.1 In 1959 the Economist, for example, noted that art ‘was better than equities’, citing Pick’s World Currency to report that Moore’s values had increased by 100% in the previous year alone.2 An article also published in 1959 ‘Appreciating Moore’ explored the phenomenon further, claiming that Moore’s ‘works have appreciated tenfold or more during the last decade and essential for them is still rising faster than supply.’3 Moore’s dealers, it reported, were maintaining waiting lists of collectors keen to get hold of works as soon as they became available. ‘Even when a new model comes forward,’ the business journal noted, borrowing its terms from the world of commodities in which these objects were patently entangled, ‘there is a time-lag before the casts are available.’

The representation of Moore’s work in financial terms was central to the ‘growth potential’ that his art promised.4 The Wall Street Journal dubbed Moore a ‘blue chip’ investment, which ‘as on the stock exchange’ offered ‘not necessarily bargains but that very attractive element of relative safety.’5 A Moore bronze acquired in 1957 for $650 by a collector in Canada, it reported, had been bought by a dealer for ‘20 times the original purchase price’, who had in turn already sold the work at ‘a very comfortable profit’.6 Such speculation-fuelled rises could be difficult to keep up with. According to one anecdote, when a Henry Moore Family Group was sold for £6,500 at auction in 1964, an art dealer rushed from the room to telephone to his gallery in order to ask his colleagues to hide an identical bronze that they had priced at merely £900.7 In the United States Moore was foremost among the artists that investors chose to capitalise on in this bullish art market. As the Dow Jones & Company financial newspaper Barron’s reported, the New York-based Growth Arts Corporation – whose investors included Sir John Rothenstein, the former director of the Tate Gallery – selected Moore for its portfolio in 1969, one of several instances where investors joined forces to ‘purchase and sell for profit works of fine art or recognisable value for both short-term as well as long-term capital growth through speculative investment.’8

It is easy to dismiss the absorption of Moore’s art into this sphere of speculation as a matter that tells us little about his art. But the monetisation of his work was not just something that happened after his creations left his studio. The post-war values of business were entangled in the practices and processes of sculptors in this period around the world, and Moore was no exception. This essay will explore the conditions that enabled Moore to become Britain’s most financially successful artist of the twentieth century. The power of his art itself is certainly chief among the reasons for his riches, but I shall focus here on Moore’s interconnected practices of standardisation and reproduction as they functioned as strategies for growth from the 1950s through to the 1970s. Finally, I shall address the mechanisms of wealth accumulation and protection, including tax minimisation and estate planning, by which Moore’s wealth was consolidated and then directed to the creation of a registered charity in 1977 to ‘encourage public appreciation of the visual arts, and in particular the works of Henry Moore’.9 In different ways, each of these practices left their mark on Moore’s art and how it came to be understood.

Standardisation and reproduction

Henry Moore

Time-Life Screen 1952–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Errol Jackson

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Time-Life Screen 1952–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Errol Jackson

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Standardisation is what I take to be the key trait that differentiates the sculpture of Moore’s late career from his earlier work, the shift that enabled the expanded production, reproduction and global distribution on which the spectacular success of his monumental bronzes depended. As he began to attract major commissions for both civic and corporate sites, Moore became decreasingly inclined to cater to the demands of individual patrons. Ignoring the thematic interests of each buyer, Moore’s commissions became generic rather than bespoke, rescaled and sited to fit their contexts, but based substantively on existing models. This shift towards what I call standardisation is suggested by Moore’s two contributions to London’s Time-Life Building: the monumental Time-Life Screen 1952–3 (fig.1), the idiosyncratic form of which responded closely to the architectural and iconographic requirements of his client, and his freestanding Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3 (fig.2), which was commissioned for the building’s private terrace but primarily inspired by the artist’s own wishes and ideas. Although the Screen was the more high profile of these commissions, it was the Draped Reclining Figure that pointed the way forward for Moore’s future success. Not the least because of the comparatively labour intensive requirements of such monumental carvings and the requirements to work with a predetermined architectural context, Moore increasingly preferred to take advantage of the flexible scale and reproducibility of cast sculpture, drawing on an inventory of existing forms and models.

Henry Moore

Sundial 1966

The Adler Planetarium and Astronomical Museum, Chicago

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Sundial 1966

The Adler Planetarium and Astronomical Museum, Chicago

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore’s statements about his artistic autonomy helped to ensure that his patrons were not offended by his generic responses to their requests and may well have struck a chord with those who supported unregulated, free enterprise. Moore’s drive towards standardisation paradoxically supported the public presentation of his art as expressive of the values of individuality and humanism, values which chimed with the ideals of almost any patron of the arts. As the art historian Pauline Rose has shown in her 2014 study of Moore’s phenomenal success in America, his work ‘was adaptable to various civic and corporate ambitions’, offering an affirmative modernism that was ‘viewed as expressing intrinsically humane qualities’.13 Appearing to stand separate from the specific interests of his public and private clients, the standardisation of Moore’s art ensured its almost infinite communicative flexibility.

Beyond matters of artistic freedom, Moore’s freestanding sculptures also offered his clients certain advantages. In the case of the Time-Life project, the company had briefly considered cancelling their commission for the Draped Reclining Figure once he had agreed to produce the fixed exterior screen for the same building. But as the architect and design consultant Hugh Casson reminded executives, the company could move the freestanding bronze as they wished (by contrast, the attachment of the screen to the exterior of the building meant that its ownership lay with Pearl Assurance, the developer of the building). ‘Financially speaking’, Casson noted, ‘Time-Life is acquiring for itself a Moore sculpture at a very reasonable price, which it can later move to a new position or dispose of, should they so wish.’14 Moore’s freestanding sculptures complied with the desire of patrons for buildings and chattels – sculptures no less than office partitions – to be flexible to changing corporate requirements.

Conscious of the potential value of Draped Reclining Figure Time Incorporated sought to clarify its status once it had been cast. Although initial correspondence had left the decision of whether the work should be made in stone or bronze to the artist, the commercial ramifications of Moore’s decision to cast it in metal became a matter of some significance.15 In 1953 the company told Moore that he could cast only one ‘second copy of this figure’, which he could ‘sell to any interested organisation – art museum, university or similar public institution – with the stipulation that this same second cast will not be sold in England or in Europe.’16 Being in the business of mass circulation themselves, Time Incorporated understood such commercial dynamics, and sought to ensure competitive advantage by limiting the sale of a second cast to a non-commercial entity, and even then, only in a market outside of their own. Further, they sought to distinguish their own sculpture – to the extent that it was possible with a bronze cast – as the authentic version of the work. ‘If you make such a sale ... the corporation would appreciate your recommendation to the purchaser that recognition be made of the fact that the original edition [sic] rests on the terrace of the Time & Life Building, London.’17

These were demands that Moore would quickly breach. In 1954, contrary to the request that a second cast should not be sold in Europe, he sold the sculpture to a museum in Cologne. Less than a year later, he wrote to request permission to make a third cast.18 The company responded disapprovingly. ‘I must tell you that we don’t welcome the idea of a third cast in Europe,’ Francis Brennan wrote. ‘Actually, we don’t much like the idea of a second cast in Europe. However what’s done is done and we shan’t ask you to undo it.’19 Judging by this letter, Moore may have insinuated that additional casts of the bronze would have been in the interests of the company. Brennan was unpersuaded. ‘While the problem of exclusivity is of course different between painting and sculpture, it is difficult to see how the existence of several copies of a fine work of art can enhance the original’, he wrote. ‘The monetary history of almost any work of art tends to prove that the value of that works runs in direct parallel to its rarity.’20 Perhaps hoping to avoid any further discussions of such a forthright nature, the artist had the collector Joseph Hirshhorn contact Time Incorporated directly to secure its permission for an additional cast. Mining magnates were evidently difficult to refuse, and with the company’s agreement there were eventually four examples of this editioned work.21

In the late 1950s Moore would come to offer the owners of unique pieces payment (in cash or in kind through additional sculptures) if they allowed him to recall a work and cast from it an edition of new works.22 Moore often agreed a relatively low price for public commissions as a philanthropic gesture (and one that increased his profile). The loss of income, however, could be more than recouped by making additional casts, which in turn could be seen as a legitimate recompense for the reduced price of the first work. Of Family Group 1948–9 made for the Barclay Secondary School at Stevenage, for example, he produced a further four casts, three of which went to customers in the United States. Decades later, Moore had a sixth and final cast of this sculpture made.23 Moore, however, did not always push his patrons to agree such steps. When the collector George Ablah asked Moore in 1985 to make new casts of older works, the artist refused to ask the current owners of the works for the necessary permission.24 However, he did make casts for himself when he could, and these sometimes made their way on to the market. The making of additional casts, beyond the edition, was and remains something of a grey area in sculptural practice.

Moore himself was well aware of the occasionally problematic nature of commercial exploitation of bronze sculpture’s reproducibility. ‘At one time I used to destroy these because of what happened to someone like Rodin,’ Moore explained of his plaster casts on the occasion of the opening of the Henry Moore Sculpture Centre in Toronto. ‘I remember Curt Valentin telling me once that there were something like eight casts for one particular Rodin sculpture, most of them made after Rodin died. To prevent this ... a sculptor will break the original terracotta or plaster.’25 ‘This was my practice until about ten years ago’, he added, claiming that the shift was motivated by the effort to preserve sculptural qualities in the ‘original’ work that might otherwise be lost in its cast.26 But this philosophical shift also allowed for a more flexible approach to production, increasing his saleable stock of work, both old and new, without requiring a substantial increase in artistic productivity.

These were dynamics that collectors understood, and which were absorbed into the public discourse concerning the value of Moore’s art. ‘If you buy a Henry Moore,’ one connoisseur of classical art explained to Time magazine, ‘you know at least half a dozen copies of the same sculpture will be cast and sold. With an ancient piece, there is only one – the original.’27 Catering to such hierarchies, Moore himself appears to have promoted his carvings for their manifest uniqueness. Writing to Moore about a proposed acquisition, banker David Rockefeller conceded, ‘I feel that the price of £6000 for the marble carving is quite fair, and understand what you mean about the alternate way of selling several bronze casts. Naturally we are very pleased to have something unique.’28

Moore’s willingness to alter edition sizes and renumber individual casts was not invisible to his patrons either. When architect Gordon Bunshaft decided not to buy one particular bronze he had been considering, his correspondence indicates his understanding of such complexities. ‘I guess you will have to change back to 0 of 9,’ he reminded Moore, indicating that this particular work should pass from the edition, numbered from 1 to 9, and become an artist proof as designated by the number 0.29 In a letter to Bunshaft about the sale of a carving, Moore reminded his client of the singular status of the stone sculpture. He explained that the gallery price for the work would normally be £20,000, of which he would receive £15,000, but that he was willing to let Bunshaft have it at less than half its price, that is, at £9,000, and reminded him that the work’s singularity represented a further sacrifice of profit: if it ‘had been in bronze, with an edition of six casts, the financial return to me would be much larger’.30

Henry Moore

Mother and Child: Egg Form 1977

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Mother and Child: Egg Form 1977

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966

Marble

overall: 660 x 585 x 410 mm

Tate T01172

Presented by the artist 1970

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore OM, CH

Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966

Tate T01172

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The commercial significance of sculptural replication was brought into sharp relief by the rise of the museum reproduction business in the 1970s. A pioneer in the field was politician and art collector Nelson Rockefeller, who in 1968 had his curator write to Moore to request that the artist ‘confirm that reproduction rights passed with ownership of the work’:

It has come to my attention that, in order to follow the recent laws of New York State, we should have from every vendor of a work of art, a release for reproduction rights ... In view of the above it is the Governor’s wish that all purchases of art be accompanied by a written instrument transferring to him the rights of reproduction thereof signed by the person owning such rights.34

Although delivered in the guise of an administrative fait accompli, Rockefeller’s request foreshadowed the art reproduction business he would launch upon his exit from politics ten years later. Sold by mail order and through the high-end department store Neiman Marcus, the Nelson Rockefeller Collection, as it was branded, reproduced some hundred works from his private collection. While the estates of Picasso, Giacometti, Nadelman and Lachaise provided licensing permission, most sculptors, including Moore, refused to cooperate.35 ‘This is an attempt to take over the last area of our culture unaffected by mass production’, blasted minimalist sculptor Carl Andre. ‘All I can wish to Nelson Rockefeller is that he fail.’36 As a result, the majority of three-dimensional reproductions marketed by Rockefeller’s new business were works of anonymous creation: artworks ranging from Benin bronzes and Japanese carvings to American folk art, were reproduced without any need to trace authorship or pay royalties.

Rockefeller’s request to Moore was not the first nor last time the artist would field requests concerning the production of three-dimensional reproductions of his work. In 1977 the retail division of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery asked Moore if it could reproduce Oval With Points 1968 – on a different scale and preferably smaller – for sale in the gallery shop.37 Moore’s response indicates his firm, if politely expressed, views on the topic. ‘I am rather taken aback by your request’, he wrote. ‘I have never agreed to this on any previous occasion – although I have had many requests to do this.’38 One of Moore’s reasons for rejecting such requests concerned the impact of reproductions on the value of his ‘original’ sculptures. ‘I think that these replicas confuse people in knowing the difference between originals and copies – and replicas cheapen the original.’39

Eva Zeisel

Pepper Pot 1947–1956

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.6

Eva Zeisel

Pepper Pot 1947–1956

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Henry Moore

Two Forms 1934

Pyinkado wood

279 x 546 x 308 mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Two Forms 1934

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Charles and Ray Eames

Full-Scale Model of Chaise Longue (La Chaise) 1948

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Fig.8

Charles and Ray Eames

Full-Scale Model of Chaise Longue (La Chaise) 1948

Museum of Modern Art, New York

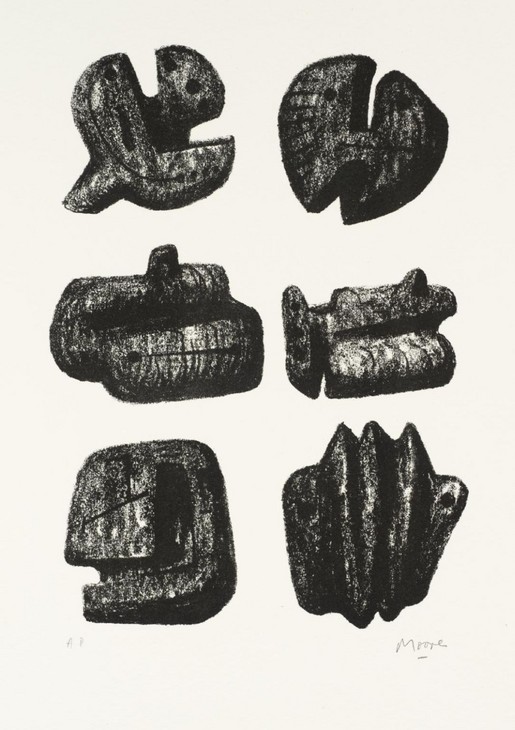

Moore himself would come to contribute directly to this field through his escalating production of graphics from the 1970s onwards. The majority of Moore’s over 700 editioned prints, an output that both propelled and sustained his commercial success, date from this period.43 These prints were typically produced with all the trappings of collectability. But occasionally Moore’s graphic work could also veer into the more straightforwardly commercial sphere – such as his 1964 wine label for Mouton Rothschild or a 1973 lithograph grid of tooled units, appearing more like machine parts than stones, published to commemorate the opening of the British Olivetti training centre in Haslemere (fig.9), or a 1983 ‘mother and child’ silk scarf design produced in an edition of 250 by Art Foulard.44 As the art world discovered the potential of multiples to market modernism to consumer market segments hitherto unimagined as within the reach of the avant-garde, Moore – in his own way – also participated in an artistic sphere cautiously enchanted by the possibilities of mass production.

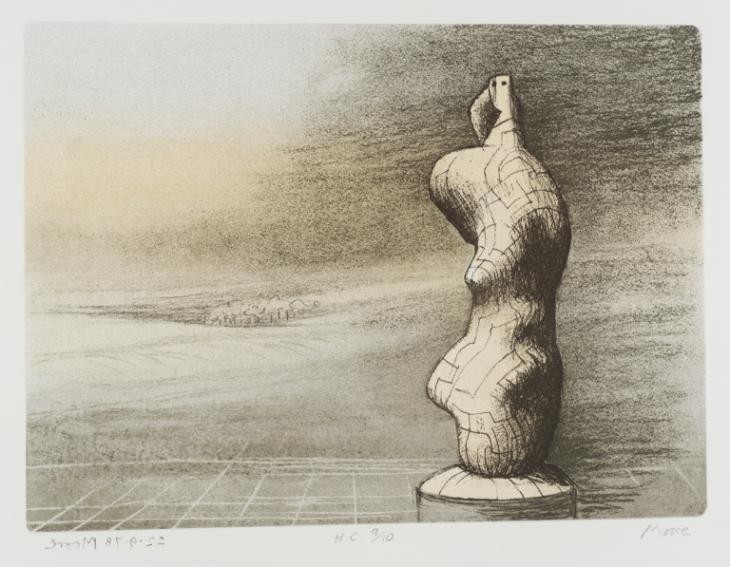

Henry Moore

Standing Figure Storm Sky 1978

Tate P02652

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Standing Figure Storm Sky 1978

Tate P02652

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Moore’s more liberal attitude to two-dimensional reproduction extended to his permissive approach to the work of photographers, whose images considerably expanded the circulation of his art. His collaboration with David Finn, the co-founder of the public relations firm Ruder & Finn, was especially significant in this field of mutual commercial interest. Finn was a significant collector of Moore’s works, and as the art historian Pauline Rose has shown, a central player in Moore’s ‘collaboration with mass media in developing himself into a household name’.46 Finn could also cast Moore in sometimes straightforwardly promotional roles. Moore was repeatedly included in Ruder & Finn’s series of Conference Room Quotations, a set of self-promotional posters featuring works of art and inspirational quotations.

Ruder & Finn also included Moore’s work in its promotional exhibition Mother and Child in Modern Art, developed for the Clairol brand of their client Bristol-Myers Squibb and toured in the early 1960s by the American Federation of Arts.47 The exhibition’s wholesome and occasionally biblical subject matter served the client’s strategic objective of counteracting the licentious reputation of dyed hair. Another minor commercial opportunity arose for Moore when Finn’s firm was retained in 1979 to handle the publicity for the new Pritzker Prize in architecture, funded by the owners of the Hyatt Hotel chain. Finn proposed that the winners of the $100,000 prize be given a sculpture as their award statuette and Moore agreed to provide an edition of nine casts of the maquette of Two Piece Reclining Figure: Cut, thereafter retitled Architectural Prize, for this purpose.48

Although typically produced in small editions of four, Moore’s monumental sculptures were also entangled in commercial strategies of multiplication. Moore and his studio used a range of theatrical illusions by which large sculptures could be produced for consideration by patrons without going to the expense of actually making them in bronze. In what David Mitchinson of the Henry Moore Foundation described as ‘a subtle piece of subterfuge’, Moore once presented Three Piece Sculpture: Vertibrae 1969 as a bronze, when, in fact, it was made from fibreglass and had been painted to resemble the green and golden-brown patination of his monumental bronzes.49 For his unrealised proposal that Double Oval 1966 should be used for the forecourt of the Chase Manhattan Bank, New York, Moore used large flat cardboard cut-outs of his design, inspecting the suitability of his proposal in situ with the art committee responsible for approving the sculptural commission.50

Moore’s decision to make use of polystyrene in his sculptural enlargements can also be seen within a range of practices that sought to produce and reproduce his work in the most cost-effective way possible. Introduced to Moore by former assistant Derek Howarth, this cheap and lightweight material substantially affected the formal possibilities of Moore’s work, suiting broad curvilinear planes and lumpen shapes, but precluding the cantilevered protrusions that had added such tension to earlier works built in plaster over an armature. Purchased in standard block sizes, the material itself reiterated the gridded methods used by Moore’s assistants to scale-up sculptures from the artist’s maquettes.51

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Reclining Figure 1951

Plaster and string

object: 1054 x 2273 x 892 mm, 271 kg

Tate T02270

Presented by the artist 1978

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore OM, CH

Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Three-Quarter Mother and Reclining Figure 1977

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Three-Quarter Mother and Reclining Figure 1977

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

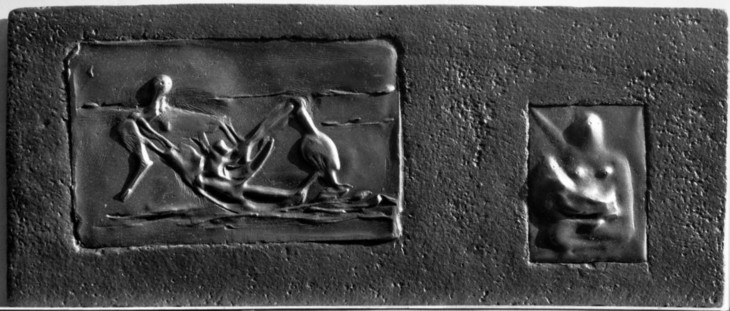

But unlike the registration of such underlying grids in the surface designs of, for example, Reclining Figure 1951 (fig.11), the appearance of figural segmentation and measurement that were essential to his studio processes was generally thoroughly concealed in their cast form.52 Only occasionally did Moore’s use of non-traditional materials seep into the final form of his works. In his shallow reliefs of the late 1970s (fig.12), small rectangular reliefs with figures appear to have been embedded in slabs of polystyrene before casting, thereby enlarging their size in the same way perhaps that Andy Warhol’s monochrome ‘blanks’ increased the surface area, and thus value, of his paintings.53 Several of Moore’s reliefs retain the surface texture of small compressed beads imprinted by the polystyrene background.54 But where artists ranging from Carl Andre to Jean Dubuffet embraced the aesthetics of polystyrene in their finished works, Moore’s use of this low-grade material would largely subsume the material’s mass-produced disposability within the timeless patinas of cast bronze.55

It was in Moore’s tense relations with the main fabricator of his monumental bronzes, Herman Noack Bildgiesserei, that the commercial pressures of his expanding practice would become most apparent. In the mid-1970s Moore all but threatened to pull his business from Noack when the founder warned that he might increase his prices. ‘My English casting costs are less than half what I have to pay you, without considering transport costs. So I am hoping that you won’t have to raise your casting costs or there will come a time when I won’t dare to risk such a big investment.’56 As Noack’s anxious reply indicates, their commercial relation was one of mutual reliance. ‘In the course of our intensive cooperation during the past 15 years I was forced more and more each year to adjust my works in accordance with your wishes.’ He concluded by making clear the ramifications of Moore’s veiled threat. ‘A large part of my firm is busy exclusively with your works. If ... there should be a reduction in the number of orders I regret having to say that I would be forced to give notice to some of my staff.’57 The commercial success of Moore’s business depended on his productive supplier relationships and, as Noack suggests, vice versa.

The fluctuations of the currency markets became a critical matter for the success of Moore’s international business. According to the Economist, for every one of Moore’s works bought in the U.K., twenty were sent abroad, notably to America where ‘prices are rather higher’.58 (Freight costs were considerable too: unlike Alexander Calder’s stabiles, which could be shipped flat for reconstruction on site, Moore’s unwieldy bronzes were hardly designed with shipping containers in mind.) In the mid-1970s both Moore and Noack were agreed that the most pressing problem for their business relationship was the ‘sharp devaluation of the Pound Sterling’.59 As Moore complained, ‘Two years ago there were nine DM’s to the pound, now there are only five, so this has nearly doubled what I pay to you.’60 Moore added a final remark in this letter that further illuminates the global nature of his late-career enterprise. ‘It is only because most of my sales are either in America, Europe and the Far East and none of them are in England that I am able to afford your casting costs.’61

One strategy to smooth Moore’s relations with Noack was the speculative casting of sculptures, building up an inventory of works available for sale to future, as yet unidentified, buyers. ‘Often I have paid you before I have found anyone who wants to buy it’, Moore emphasised to Noack, ‘and so with such huge expenses I am taking a very great risk.’62 But by building up such a stock in trade, Moore reduced the delay in fulfilling orders for monumental bronzes. As a letter from Noack to Moore’s dealer indicates, the delay in producing such works was an ongoing problem:

Since December of last year we have shipped sculptures and commenced some which have a value of DM 300,000. If we keep this speed we will have a balance of DM 1.2 million this year. You are therefore not very grateful if you say we work and deliver slow, especially since we try very hard to complete big sculptures as quickly as possible and on very short notice ... I do not think you will find another company who do the work as quickly as we do.63

In this instance, and no doubt in others, the growth of Moore’s enterprise had profound impacts throughout his supply chain. Noack had employed more staff in order to keep up with the demand for Moore’s art. ‘In spite of the continuous work on big sculpture we also do small and medium sized casts’, work, which Noack explained, did not slow down the monumental sculptures as ‘not every worker can work exclusively on big casts’.64

Accumulation and protection

Managing the vicissitudes of standardisation and reproduction, Moore’s art became inextricably implicated in capital accumulation and wealth protection at a scale as grand as his art. His largest patrons bought work voraciously. Joseph Hirschhorn owned more than fifty artworks by Moore when he gave his collection to found a new public museum in Washington D.C. This was more than he owned of any other artist he had collected in the years which, as the New York Times put it, marked the ‘speculator’s transfiguration into a national asset.’65 Even more spectacularly, Kansan real estate developer and Koch Industries partner, George Ablah, acquired more than one hundred Moore sculptures in the late 1970s before selling many of them to a Japanese buyer at considerable profit. Such patrons may not have collected art as an investment first and foremost but they were careful to ensure that their ownership of artworks helped rather than hindered their portfolio as a whole. Their practices were ones which Moore himself would come to imitate.

‘Wealth beyond the dreams of most men could have come his way had he not disdained all devices for tax avoidance’, wrote John Russell in 1973, a remark that was probably prompted by Moore’s comments to the critic about the amount of tax he had paid to date.66 In the following years the impact of wealth taxes on the careers of leading British artists became a matter of public discussion. The Labour government arrived in office in 1974 with the promise of introducing a wealth tax, a policy that had ensured trade union support during the election.67 ‘Redistribute income and wealth’ read the party manifesto. ‘We shall introduce an annual Wealth Tax on the rich; bring in a new tax on major transfers of personal wealth’ and ‘heavily tax speculation in property’.68 As part of a sweeping program designed to ‘eliminate tax dodging’, the proposal affected individuals whose assets exceeded £100,000. This constituted only 1% of the population and although he was far from the only artist in this category, the scale of Moore’s holdings of his own work meant that the impact of the taxation changes, had they been implemented, would have hit him more than any other living artist in Britain.

The proposal was a subject of considerable ideological division within the arts community. In the House of Lords Sir Kenneth Clark admitted that ‘collecting has now become, like the Stock Exchange, a form of gambling and tax evasion’ but argued against the extension of the wealth tax to works of art because, as the Times paraphrased his speech, it would be ‘hard not to penalize those who had bought or inherited works of art for very different reasons’.69 For art dealer Hugh Leggatt the policy represented nothing less than a conspiracy to confiscate private artworks for the benefit of state collections: ‘Government policy, in connection with its proposal not to exclude works of art from the wealth tax’, he wrote, ‘appears to envisage the passage, by a form of long-term cryptoconfsication, of the large numbers of such works into public possession.’70 The critic Peter Fuller, by contrast, argued that that if art was indeed exempted from the wealth tax, it would become a kind of tax haven for the wealthy, and there would be ‘a decisive movement of capital into canvas, marble, bronze and furniture and prices would soar.’71 The result, he predicted, would cripple the buying power of public museums and ensure that artworks would be even ‘hoarded to the financial advantage of the few’ to an even greater extent.’72 Art historian Denis Mahon pointed out that an increase in the tax burden for British collectors would only be to the advantage of American purchasers who already ‘enjoy tax concessions and a stronger currency’.73

Some artists – including those whose once resolute commitment to socialism might have favoured the principles of wealth redistribution that underpinned the proposal – lobbied hard against the changes. In a letter published in the Times, which was signed by Moore and thirty-three others, it was argued that the increased taxation of art would ‘discourage discriminating patrons from purchasing works’, in turn diminishing sales.74 But, more importantly, the artists claimed that it was a ‘threat of almost unbelievable imbecility’ to tax artists on the works they owned. ‘That the living artist will be liable for tax on his “stock” of unsold works ... can only encourage him either to emigrate or cease working.’75 The letter conceded that there was a perception that art collecting had become primarily a vehicle for investment but the artists insisted, ‘Artistic discrimination is not a matter of money or speculation’.76

Moore’s participation in this lobbying against the eventually abandoned wealth tax was but one of the ways in which he had to grapple with the taxable status his sculpture. In the United States Republican senator Jacob Javits and lawyer and Moore collector R. Sturgis Ingersoll had formed the National Committee to Liberalize the Tariff Laws for Art in 1959. While the more famous case of Brancusi’s Bird in Space being taxed as a ‘manufactured metal implement’ was the group’s prime case study, its lobbying activities also repeatedly used the import taxes assessed on Moore’s art as evidence of the problem with US customs. In a New York Times article in support of their campaign it was reported that Moore’s Two Forms 1936 had been deemed by customs a ‘manufacture of wood’ and had been declared dutiable at 33.3%.77 According to another article, the problem for Moore was compounded by his choice of ‘non-committal titles’ because works of art were required to be ‘representational’ under the regulations (an abstract sculpture could enter the country duty-free if titled Flower or Reclining Figure).78 Moore’s experience with such regulations would become part and parcel of his increasingly global business activities.

When the artist wrote to Margaret Thatcher in 1979, soon after she became Prime Minister, to complain that he had paid a total of £4,350,621 of tax in the ten years leading up to 1977, Moore had already put in place structures to ensure that the next decade would not see the same withering of his income by Inland Revenue.79 He established the Henry Moore Trust in 1972, transferring part of the Hoglands estate to the Trust so that it could be preserved as a sculpture park, and thereby ensuring that it would not have to be sold to pay death duties at the end of his life. The ownership of many works of art had also already been transferred to Moore’s wife and daughter.80 Although the stated aim of the trust was ‘the advancement of education in the fine arts and sculpture in particular’, these adjustments were also patently intended to protect his financial interests.

In 1977 two new entities of lasting public significance were created. The first was the Henry Moore Foundation, with goals similar to those stated by the existing Trust. Owing to its non-profit status, the Foundation was unable to trade, such that a commercial subsidiary known as Raymond Spencer Ltd, named after Moore’s father, also had to be established. The latter company, of which Moore was Managing Director, paid Moore a salary and owned his new works. The catalogue of Moore’s drawings notes that the artist ‘made all his drawings after 1977 for Raymond Spencer Company, the trading arm of the Henry Moore Foundation, the name of which was changed to HMF Enterprises in 1991’.81 Unlike the partial transfers of property undertaken for the trust, this restructure had more sweeping impact on the ownership of Moore’s assets. As David Mitchinson explained, ‘Moore transferred the resources of his profession – tools, materials and the means of production including his employees – to the company, in return for shares which he gave to the foundation.’82

The complexities arising from these structures have been vividly reconstructed by Mitchinson in his contribution to Celebrating Moore (2006). ‘As the company handled sales, while the Foundation dealt with exhibition requests’, he wrote, ‘a situation soon developed whereby the company was selling works from the foundation while the Foundation was lending items from the company.’83 The fluidity with which assets moved between Moore’s commercial enterprise designed to sell his sculpture and his non-profit entity conceived to do the opposite was exacerbated by the multiple nature of Moore’s cast sculpture, and the potential for the ownership of individual works to be confused or ignored. ‘Moore’s insistence that everything should be credited to the Foundation as the lender even in cases where the Company rather than the Foundation was the owner might have made sense at a time when he was trying to promote the Foundation’s name and identity, but would give rise to serious confusion over the ownership of individual casts for years to come.’84 More problematic still, when it came to sales, Moore continued to treat ‘everything’ at Perry Green as ‘stock in trade’ which ‘could in practice be offered for sale.85

Like the complexities of ownership that characterised the affairs of his commercial patrons, Moore’s own enterprise was reshaped in the image of the financial and legal structures that defined post-war capitalism. But the fact that Moore was trading under such entities could also sometimes cause confusion for his customers. Even those who might have been attuned to the pragmatic aspects of the structures through which Moore sold works sometimes expressed a desire to be buying works from the artist rather than from an incorporated company. ‘I know that these bills could only come from Henry Moore’, complained Gordon Bunshaft, ‘but actually there is no indication that this piece was done by Henry Moore or that the insurance value was done by Henry Moore – so, I would appreciate it if you would sign each of these papers and return them to me.’86 Henry Moore was no longer simply an artist: his enterprise, like his sculpture, had ‘gone public’, and his name was the trading identity around which an operation much larger than one man had been built.

There were limits, however, to Moore’s commercial orientation. The artist refused to allow a computer at his home in Perry Green, for example, on the grounds that its presence would make the operation ‘seem like a business.’87 Such resistance was no doubt generational, but the basis of the prohibition for its potential impact on Moore’s image powerfully suggests the fundamental tensions between art and commerce in Moore’s later career. In the mid-1960s Alfred Barr, Director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a longstanding admirer of Moore’s work, expressed concern that the artist he had once so enthusiastically championed was becoming a ‘businessman’s sculptor’, as a private note in the papers of a colleague records.88

As Moore’s financial success increasingly rubbed up against the discourses of humanism embodied in his sculpture, the question of how the ‘value’ of Moore’s art was to be understood elicited considerable anxiety within the art world. As curator Chris Stephens has put it, as Moore became a ‘global, popular and influential figure, a sense of the ubiquity of his work brought about a backlash’, a fate that was ‘not helped by his eagerness to exploit sculpture’s potential for multiplication.’89 But the tensions between Moore’s status as a symbol of civilisation and humanity and the seemingly contrary aspects of productivity, popularity and profit associated with his late career should not be seen as completely irreconcilable drives, or even rationalised as a path from youthful idealism to late-career pragmatism. Both forces were present in Moore’s art from the beginning, and perhaps, in modernism itself. These are the mutually reliant spheres of culture and commerce that successful artists have always had to negotiate.

To provide a concluding suggestion of such tensions, here is a wholly typical lament of the absorption of art into the shallow world of commodities from the pages of a newspaper. It dates from 1968, and although it could have been written at almost any point in the twentieth century, its anachronistic simile speaks to the power of Moore’s style to appear at once modern and also timeless. ‘The pressure of the market is now upon the artist, like the Philistines upon Sampson,’ wrote David Pryce-Jones at the end of the 1960s. An artist was now forced to ‘produce quickly something which catches the commercial eye,’ and then ‘having captured or created a fashion ... [was] obliged to repeat himself before being overtaken by the next wave.’ But for Pryce-Jones, writing for the audience of the Financial Times, Moore’s art could still appear to represent art’s stand against fashion and popular taste, and serve as an exemplar of ‘the last generation of artists relatively free from commercialisation’.90 For such writers the appeal of Henry Moore depended very much on the belief that his art declared its resistance to the values of late twentieth-century capitalism, even if – no less than slick industrial sculpture or crassly commercial pop – its imperatives were ones in which his art was unavoidably entangled.91

Notes

For a broader account of this phenomenon, and its ripples in an entirely different artistic field, see Sophie Cras, ‘Art as an Investment and Artistic Shareholding Experiments in the 1960s’, American Art, vol.27, no.1, Spring 2013.

J. Richard Elliott, ‘The Monet Game: For Connoisseurs of Art or Plain Investors: A New Market Guide’, Barron's National Business and Financial Weekly, 10 November 1969, p.9. See also Michael White, ‘London Letter’, Guardian, 22 March 1974, p.13.

On these and other projects for specific corporate contexts, see Anita Feldman, Henry Moore and the Challenge of Architecture, Much Hadham 2005.

Pauline Rose, Henry Moore in America: Art, Business and the Special Relationship, London 2014, pp.2, 42.

Hugh Casson, letter to H. Maurice Lancaster, 7 July 1952, p.2, Sir Hugh Casson Archive, Victoria & Albert Museum Archives.

Hugh Casson, letter to Henry Moore, 18 December 1951, p.2, Sir Hugh Casson Archive, Victoria & Albert Museum Archives.

This appears to have been for a private collection in Basel, Switzerland, planned as an eventual museum donation. The letter also mentions a possible cast for São Paulo. See Francis Brennan, letter to Henry Moore, 19 October 1953, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Entry for Family Group 1948–9, Henry Moore Foundation, http://www.henry-moore.org/works-in-public/world/japan/hakone/open-air-museum/family-group-1948-49-lh-269 , accessed 6 August 2014.

Gordon Bunshaft, letter to Henry Moore, 1 December 1970, p.1, Henry Moore Foundation Archive. The work in question seems to be a cast of Square Form, a piece derived from 1930s works and related to the Time-Life Screen. In another instance, two casts of the same work would be inscribed 0/9, signalling an artist copy. See David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.20.

Carole K. Uht, letter to Henry Moore, 8 November 1968, Record 4, Art Series. Nelson A. Rockefeller Papers, Rockefeller Archive Center.

The estates of David Smith and Aristide Maillol also refused. In the case of Rodin and Degas, lapsed copyright enabled their reproduction without permission (or, at least, that appears to be the advice given by Rockefeller’s legal counsel). See Grace Glueck, ‘Rockefeller Calls Parley on Art’, New York Times, 17 January 1979, p.C15.

Quoted in Carole Korzeniowsky, ‘A Rockefeller Art Storm’, Financial Times, 30 December 1978, p.12. This article also lists Moore’s name among artists that turned down Rockefeller’s requests.

Leta K. Stathacos, letter to Henry Moore, 30 December 1977, p.1, Henry Moore Foundation Archive. The work had been donated to the museum by Gordon Bunshaft.

See Brooke Kamin Rapaport and Kevin Stayton, Vital Forms: American Art and Design in the Atomic Age, 1940–1960, New York 2001, p.155.

The name of La Chaise was a deliberate play on the name of sculptor Gaston Lachaise. See Pat Kirkham, Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century, Cambridge, Massachusetts 2001, p.453. Due to high manufacturing costs, the design did not go into production until 1990.

Of the four-volume catalogue of Moore’s graphics, only the first volume deals with works made before 1972.

See Ann Garrould, Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Drawings 1950–76, London 1994–2003, vol.4, p.162; Gerald Cramer, Henry Moore: Catalogue of Graphic Work, Geneva 1973–1986, vol.1, no.57, and vol.2, no.300.

The exhibition included graphics by Henry Moore, Marc Chagall and Henri Matisse from ‘The Clairol Collection, New York’. See Mother and Child 1963–6, American Federation of Arts records, Archives of American Art, box 60.

The inaugural prize was given to Philip Johnson. See Rose 2014, pp.194–7, and David Finn, The Way Forward: My First Fifty Years at Ruder Finn, New York 1998, p.136.

Such processes are recounted in Anne Wagner, ‘Scale in Sculpture: The Sixties and Henry Moore’, Tate Papers, no.15, Spring 2011, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/scale-sculpture-sixties-and-henry-moore , accessed 31 July 2014.

Another work that notably registers the line-work common to the underlying geometries of Moore’s studio processes and an occasionally cartographic drawing style is Three Quarter Figure: Lines 1980.

On Warhol’s use of ‘blanks’ as a strategy to increase the value of his paintings, see Benjamin Buchloh, Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, Cambridge 2000, p.492.

See, for example, Relief: Two Seated Mother and Child 1979 in Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 5: Complete Sculpture 1974–80, London 1988, no.774.

Hermann Noack undated, letter to Harry Fischer, Marlborough Fine Art, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Vivien Haynor, ‘Joseph Hirshhorn’s Mine of Modern Art’, New York Times Magazine, 27 November 1966, p.69.

Howard Glennerster, ‘A Wealth Tax Abandoned: The Role of the UK Treasury 1974–6’, CASEpapers, 2011, no.147.

Peter Fuller, ‘Why a Wealth Tax Could Bring Private Collections into the Open’, Times, 10 May 1975, p.14.

Dennis Mahon, ‘A Wealth Tax on Works of Art: Will the Minister Be Asked to Think Again?’, Times, 9 June 1975, p.14.

‘Wealth Tax and the Living Artist’, Times, 10 September 1975, p.15. Other signatories included Kenneth Armitage, Francis Bacon, Reg Butler, Richard Hamilton, Allen Jones, Bernard Meadows, John Piper and Joe Tilson.

Ibid. A further letter on the matter, signed by Moore and seven of the original signatories, was published later the next month. See Richard Hamilton, ‘Wealth Tax and the Living Artist’, Times, 31 October 1975, p.15.

‘But Is It Art or Colored Glass’, New York Times, 9 August 1959, p.SM28. As the article admitted, the regulations had been relaxed by 1959 such that Moore’s sculpture could enter the United States as ‘art not specially provided for’ at 10% duty – an additional cost for those collectors who purchased directly from the sculptor rather than his New York representative.

‘Chase: Don’t Use AHB’s Name!’, handwritten note, undated, box 14, folder 4, Dorothy Miller Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Alex J. Taylor is the Terra Foundation Research Fellow in American Art at Tate.

How to cite

Alex J. Taylor, ‘Henry Moore and the Values of Business’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www