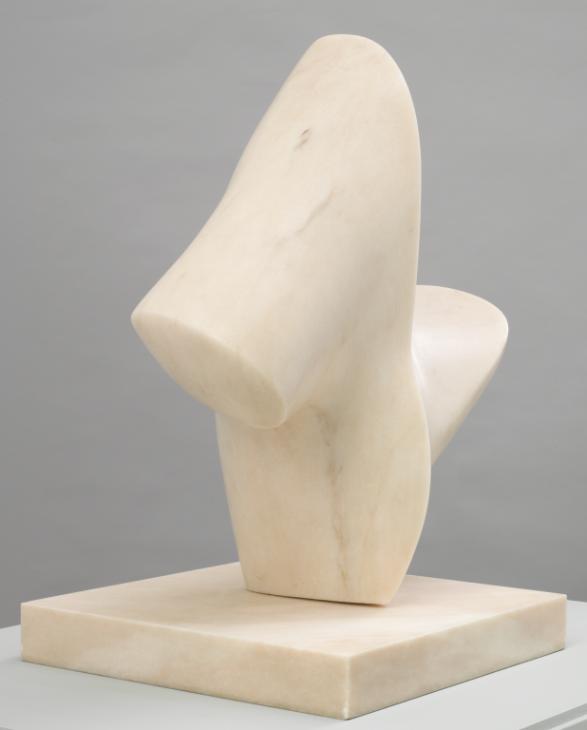

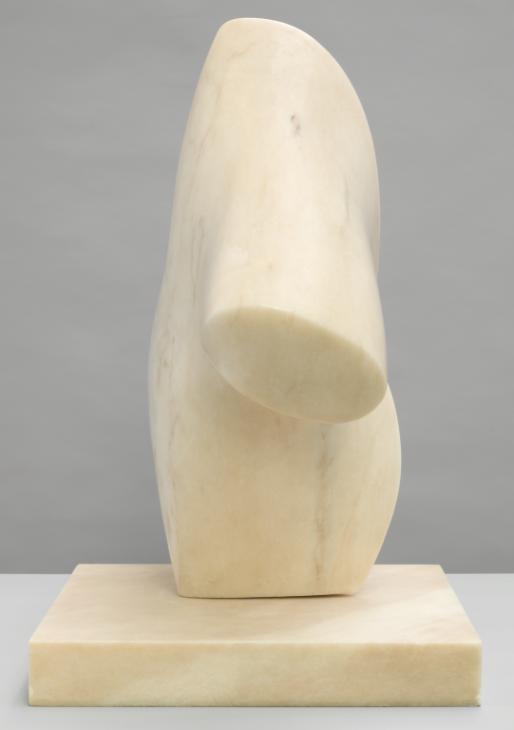

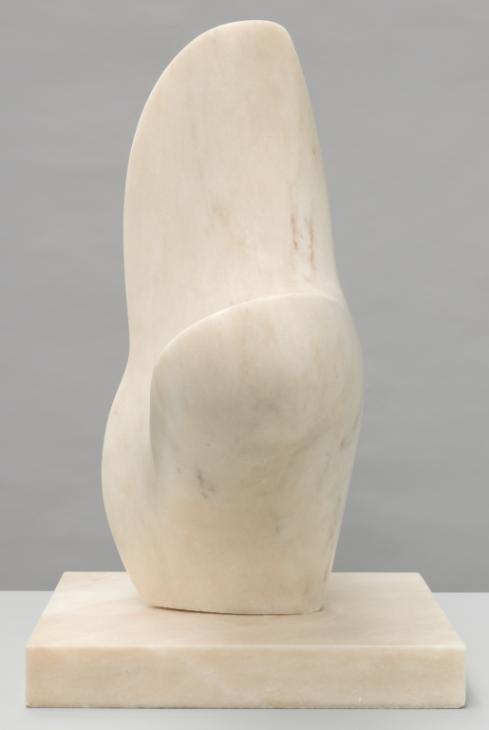

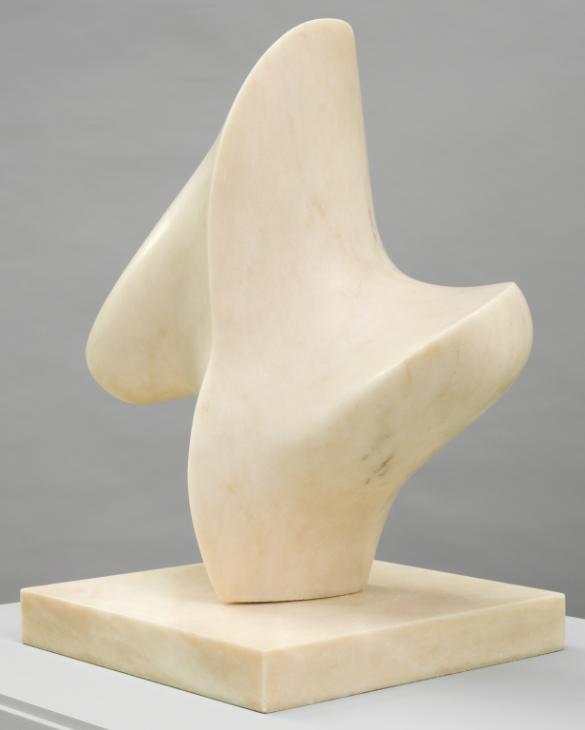

Henry Moore OM, CH Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966

Image 1 of 13

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Upright Form: Knife Edge

1966

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966 was carved in Italy from a single block of marble and was donated by Moore to Tate in 1970 in memory of his friend, the critic Herbert Read. The sculpture’s dynamic, sharp-edged forms are illustrative of Moore’s re-engagement with abstraction in the 1960s.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Upright Form: Knife Edge

1966

Portuguese Rosa Aurora marble

660 x 585 x 410 mm

Presented by the artist 1970

T01172

Upright Form: Knife Edge

1966

Portuguese Rosa Aurora marble

660 x 585 x 410 mm

Presented by the artist 1970

T01172

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1970 in memory of Sir Herbert Read.

Exhibition history

1970

Herbert Read Memorial Exhibition, Tate Gallery, March 1970, no number.

1973

Henry Moore to Gilbert & George: Modern British Art from the Tate Gallery, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, September–November 1973, no.44.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983, no number.

2001

Breaking the Mould: 20th Century British Sculpture from Tate, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich, July–September 2001, no.9.

2012

Henry Moore at the Kremlin, Moscow Kremlin Museum, Moscow, February–May 2012.

References

1967

Henry Moore Carvings 1923–1966, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1967 (white marble version reproduced).

1968

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo 1968 (white marble version reproduced no.119).

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, pp.118–25.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.209 (white marble version reproduced pl.224).

1970

Henry Moore: Carvings 1961–70, Bronzes 1961–70, exhibition catalogue, M. Knoedler & Co., New York 1970 (white marble version reproduced p.15).

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973 (white marble version reproduced pl.151).

1973

Henry Moore to Gilbert & George: Modern British Art from the Tate Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels 1973, reproduced p.53.

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977, no.551, reproduced pls.44–5.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.59.

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983., reproduced p.100.

2001

Breaking the Mould: 20th Century British Sculpture from Tate, exhibition catalogue, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich 2001, p.17.

2013

Alice Correia, ‘A Gift of Sculpture: Henry Moore at Tate’, Tate Etc, Summer 2013, pp.74–5, reproduced p.75.

Technique and condition

This abstract sculpture was carved from a square block of pale pink marble and is mounted on a base made of the same stone. The surfaces, including the base, have been smoothed to a fine satin finish and there are no signs of tool marks. The marble is coloured with some rusty red veining, particularly on one side (fig.1).

In 1965 Henry Moore purchased a holiday cottage with a carving studio in Forte dei Marmi, Italy. This was conveniently placed near a stone company called Henraux in Querceta, which own the Altissimo mountain, a rich source of marble once used by Michelangelo. It was from their stoneyards that Moore chose the block of Portuguese Rosa Aurora marble for this sculpture.

The design for this sculpture was originally modelled in clay on a smaller scale (fig.2). Before carving the full-size final version in marble the shape of the sculpture would be marked out on the square stone block and the larger unwanted parts would be removed using a hammer and point chisel. This tool concentrates the force of the blow onto a small area and breaks off sections of stone quickly. The point chisel is often used to remove stone to within one and three centimetres of the final surface. Once the outline of the shape was roughed out in this way a range of claw chisels would be used to carve the sculpture. These have broad blades with teeth that allow the sculptor to remove stone relatively quickly and refine the form. The next stage of the process would have involved using various sizes of flat chisels to remove the furrows in the surface left by the claw chisels. The contours of the sculpture were then perfected with rasps and files to make the surface more uniform. Finally, the marble would have been smoothed by working through the grades of abrasive from coarse to fine in order to produce a satin finish.

The sculpture is mounted over a stainless steel rod that rises up through the base. This rod has become slightly bent so the sculpture does not sit flat on the base (fig.3). As a consequence this has put uneven pressure on the lower edge of the sculpture and has led to some chipping (fig.4). The circular white marks around the point where the sculpture is fixed to the base have been caused by abrasion where the sculpture has swivelled on its mounting rod.

Detail of Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966 showing gap above base

Tate T01172

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966 showing gap above base

Tate T01172

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966 Detail of chipping at the foot

Tate T01172

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966 Detail of chipping at the foot

Tate T01172

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Lyndsey Morgan

January 2014

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', January 2014, in Alice Correia, ‘Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Upright Form: Knife Edge is an abstract sculpture carved from Portuguese Rosa Aurora marble, which is pale pink in colour. The sculpture is mounted on a square base of the same material, from which it rises vertically (fig.1). A sharp pointed central spine extends upwards and outwards from the elliptical footprint at the bottom before curving inwards to a fine point at the top. Projecting laterally from either side of this vertical axis are two spurs. One appears to rise outwards from near the base and has a rounded, diagonal underside and an almost horizontal upper surface. The spur on the other side is more cylindrical in form and has an upper side that points at a downward diagonal from the apex and a shorter, near-horizontal underside. While the upwards pointing spur terminates in a curved point, the other appears truncated and ends abruptly in a flat oval face. The sculpture is not positioned centrally on the base and both of the extending spurs project beyond the width of the base below.

The sculpture slots onto a metal pole that runs up through the base. This rod is bent slightly so the sculpture does not sit flush on the base (fig.2). The front edge is slightly raised and there are circular scratches on the upper surface of the base. These suggest that the sculpture has swivelled or rotated, abrading the surface beneath.

Making Upright Form: Knife Edge

Before carving this sculpture in marble Moore first modelled its design in white clay. The small-scale maquette for Upright Form: Knife Edge was made in 1966 in the maquette studio on the grounds of his home, Hoglands, in Perry Green, Hertfordshire, and remains in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation (fig.3). This studio was lined with shelves displaying Moore’s ever growing collection of found bones, shells and flint stones, the shapes of which often served as starting points for Moore’s formal experiments in three dimensions.

Upright Form: Knife Edge was carved in the summer of 1966 while Moore was staying at his holiday home in Forte dei Marmi, Italy. Moore purchased the property the previous year and spent two or three months there every summer until the mid-1970s. Forte dei Marmi is in northern Tuscany near the Carrara mountains, which are

famous for being a rich source of marble. Moore’s cottage was conveniently located near the Société S. Henraux quarry at Querceta, where he had worked during the winter of 1957–8 carving the full-size Unesco Reclining Figure in travertine marble (see Tate T00390). This commission had reinvigorated Moore’s interest in stone carving after a period working in plaster for bronze casting. According to the former Tate curator Michael Compton, Moore wandered around the Société S. Henraux stone yard where he found a piece of Rosa Aurora marble imported from Portugal, and it was from this block that Upright Form: Knife Edge was carved.1

famous for being a rich source of marble. Moore’s cottage was conveniently located near the Société S. Henraux quarry at Querceta, where he had worked during the winter of 1957–8 carving the full-size Unesco Reclining Figure in travertine marble (see Tate T00390). This commission had reinvigorated Moore’s interest in stone carving after a period working in plaster for bronze casting. According to the former Tate curator Michael Compton, Moore wandered around the Société S. Henraux stone yard where he found a piece of Rosa Aurora marble imported from Portugal, and it was from this block that Upright Form: Knife Edge was carved.1

Henry Moore

Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966

White marble

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Oppositional forces

Upright Form: Knife Edge and its white counterpart are two of four ‘knife edge’ abstract sculptures made by Moore during the 1960s (see also Working Model for Knife Edge Two-Piece 1962, Tate T00603). In 1968 the critic and curator David Sylvester identified Upright Form: Knife Edge as belonging to a group of sculptures in which Moore explored the interplay between ‘hard and soft’ forms.4 Sylvester argued that this interest represented a new development in Moore’s work, and was the direct result of the artist’s earlier decision to make sculptures out of plaster that could then be cast in bronze. Moore found that plaster was a malleable and flexible material from which hard and fine forms could be articulated. According to Sylvester, Moore then transferred his knowledge of the aesthetic potential of plaster to his marble sculptures, although he noted that the ‘soft’ qualities of the Rosa Aurora marble undermined the sharpness of the vertical edge of Upright Form: Knife Edge.5

For Sylvester the development of contrasting hard and soft forms ‘represented a radically new way of thinking for Moore’, one that emphasised dynamic rather than static qualities.6 To support this interpretation, Sylvester cited Moore at length:

This is, perhaps, what makes me interested in bones as much as flesh, because the bone is the inner structure of all living form. It’s the bone that pushes out from the inside; as you bend your leg the knee gets tautness over it, and it’s there that the movement and energy come from. If you clench a knuckle, you clench a fist, you get in that sense the bones, the knuckles, pushing through, giving a force that, if you open your hand and just have it relaxed, you don’t feel. And so the knee, the shoulder, the skull, the forehead, the part where from inside you get a sense of pressure of the bone outwards – these for me are the key points.7

For Sylvester, it was the contrast between the sense of movement and the stillness of sculptures such as Upright Form: Knife Edge that illustrated the evolution of Moore’s artistic thinking. However, these may not have been entirely new concerns for Moore, whose statements from the 1930s, when he was preoccupied with direct carving, express a similar interest in oppositional forces. Indeed, an essay written for the publication Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture in 1934 may also account for the tension between static and dynamic forms in Upright Form: Knife Edge:

When the sculptor understands his material, has a knowledge of its possibilities and its constructive build, it is possible to keep within its limitations and yet turn an inert block into a composition which has a full form-existence, with masses of varied size and section conceived in their air-surrounded entirety, stressing and straining, thrusting and opposing each other in spatial relationship – being static, in the sense that the centre of gravity lies within the base (and does not seem to be falling over or moving off its base) – and yet having an alert dynamic tension between its parts.8

The fact that Moore chose to present Upright Form: Knife Edge to Tate in memory of his friend, the critic Herbert Read, serves to support the connections between this work and Moore’s artistic preoccupations of the 1930s, for it was during that decade that their friendship was closest. Read edited Unit One and described Moore’s statement as ‘excellent + I don’t want you to add to it or alter it in any way’.9 The longevity of their friendship and the convictions they shared led Moore to believe that Read would have approved of the forms and materials of Upright Form: Knife Edge.10

In memory of Herbert Read

From 1965 until his death in 1968 Read had sat on the Board of Trustees of the Tate Gallery, the first professional art historian to do so. Following his death, and with the desire to recognise Read’s unique contribution to the development and promotion of British art, Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Naum Gabo and Ben Nicholson agreed to donate works to Tate in his memory.11 Moore had not previously exhibited the Rosa Aurora version of Upright Form: Knife Edge and for several years it sat on a table in the artist’s living room at Hoglands.

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery June–August 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery June–August 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Alice Correia

March 2014

Notes

See [Michael Compton], ‘Henry Moore, Upright Form (Knife Edge) 1966’, in The Tate Gallery 1968–70, London 1970, p.94. The critic John Russell noted in 1968 that at Henraux, ‘an abundance of fine stone is constantly to hand, and Henraux’s often import exotic rarities in the way of business’. See John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.209.

See Lot 497, Sale 1901, Impressionist And Modern Art Day Sale, Christie’s, New York, 7 November 2007, http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/LotDetailsPrintable.aspx?intObjectID=4984010 , accessed 18 March 2014.

Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, pp.29–30, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, pp.191–2.

See http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibitionseries/henry-moore-display , accessed 17 March 2014.

Related essays

- ‘A stimulation to greater effort of living’: The Importance of Henry Moore’s ‘credible compromise’ to Herbert Read’s Aesthetics and Politics Ben Cranfield

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Henry Moore and Direct Carving: Technique, Concept, Context Sarah Victoria Turner

- Circling Each Other: Henry Moore and Adrian Stokes Richard Read

- Henry Moore and Stone: Methods and Materials Sebastiano Barassi and James Copper

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Upright Form: Knife Edge 1966 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www