The Camden Town Group: Then and Now

Ysanne Holt

The character and achievements of the Camden Town Group have been interpreted in different ways over the last century by critics and art historians. Ysanne Holt explores the history of the group and discusses problems of definition and interpretation that continue to shape understanding of Camden Town painting today.

First appearing at the Carfax Gallery in London’s St James’s in June 1911, the newly formed Camden Town Group, headed by Walter Sickert with an inner circle of Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman, Charles Ginner and Robert Bevan, received widespread critical attention and support. In the ferment of new exhibiting societies, cliques and rival formations that emerged in the capital in the years leading up to the Great War, the Camden Town Group was quickly recognised by contemporaries for its commitment to truthful observation and for what the literary critic and historian Samuel Hynes has termed its ‘fidelity to the present’.1 As the art critic Charles Marriott remarked in his review entitled ‘Here and Now’ of the second Carfax show of December 1911, ‘whatever else these young artists may or may not be doing, they are treating art as if it had something to do with contemporary life. They paint music halls, hansom cabs, coster girls, back gardens and even back bedrooms.’2 Negotiating a course between the more overtly radical factions of the period and what was by then perceived as the growing conservatism of existing societies like the once Francophile New English Art Club (NEAC), the group’s core membership created works whose distinctive character is of enormous value in our assessment of an extraordinary era of rapid social and cultural transformation.

By the early twentieth century London was the largest, most socially diverse and cosmopolitan city in Europe and capital of the world’s largest empire.3 With an inner-city population of over 4,500,000 in 1901, the year of Queen Victoria’s death, the city was characterised by new forms of leisure and consumption, shifting class and gender relations, new spatial geographies and enhanced mobility, evolving modes of publicity – including the writing about, display and consumption of art – as well as an ever more rapid circulation of images. It is within this dynamic social and cultural context that Sickert reasserted his belief, first declared in his 1889 introduction to an exhibition at the Goupil Gallery of paintings by the ‘London Impressionists’, ‘that for those who live in the most wonderful and complex city in the world, the most fruitful course of study lies in a persistent effort to render the magic and the poetry which they daily see around them’.4 Sickert’s statement epitomised the ambitions of those late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists concerned with the conditions and experience of everyday life in the metropolis. Indeed, it underlines his own particular taste for the shabbier music halls of the north London suburb of Camden Town, sites like the Old Bedford, where, as the cultural historian Peter Brooker records, ‘English vaudeville and French exoticism combined in an idiom of “doubles entendres”’.5

Any outline of the evolution of the Camden Town Group and the importance of Sickert’s work to its members is profoundly indebted to the scholarship of Wendy Baron.6 Baron has examined in close detail the period of Sickert’s initial membership of the NEAC where, in 1888, he showed his painting of the performer Katie Lawrence on stage at Gatti’s Hungerford Palace of Varieties in Charing Cross. That same show included Philip Wilson Steer’s equally technically advanced beach scene A Summer’s Evening 1888–9 (private collection). Both works revealed the marked influence of Edgar Degas and Claude Monet respectively, at a time when many critics were largely hostile to the effects of recent French painting on younger British artists. Sickert’s painting demonstrated overtly the impact of his 1883 and 1885 meetings in France with Degas and the subsequent decline in his affinity for the American-born painter and early mentor James Abbott McNeill Whistler, whose works he would come to regard as excessively tasteful – a sensibility which he declared was ‘the death of the painter’.7 Whistler’s refined washes of paint and his alla prima technique were increasingly replaced in Sickert’s estimation by the working practices of Degas, shown in his compositional devices and unusual perspectives as well as his choice of subjects – the café life and entertainment scenes associated with contemporary Parisian society.8 Sickert’s attempt in 1889 at an ‘impressionist clique’ takeover of the NEAC has been regarded as his bid to establish an equivalent representation of the specifically characteristic forms of London life.9 As the critic Charles Marriot observed, Sickert ‘translates absinthe into beer’.10

However, by the following decade, in a period of wider cultural conservatism, Sickert’s aspirations to form a dominating clique faltered. This, alongside the end of his first marriage to Ellen Cobden, accounted for his departure in 1898 for Dieppe and later for Venice. For the next seven years he produced topographical subjects and landscapes as well as the type of interior nudes and double figure compositions he would restage within drab Camden Town interiors after his return to London in 1905.11

That return was prompted by his visitors in Dieppe in 1904: Albert Rutherston, younger brother of painter and Carfax Gallery advisor William Rothenstein, and Spencer Gore, a former student of the Slade, the most advanced art school of the period, where his tutors included Steer, Henry Tonks and Fred Brown, all dominating figures at the NEAC. To Rutherston, looking back nostalgically following Sickert’s death in 1942,

Sickert seemed to become at once our natural leader, possibly because he lived more intimately with us than gods of longer standing, in spite of their friendly hospitality ... His methods of work, his way of life, his wit, brought a fresh and inspiring atmosphere. Above all he seemed the perfect cosmopolitan figure who had worked alongside Degas, who knew France intimately and had won our admiration by his work of Dieppe and Venice together with that of the earlier London of the 1890s.12

The attentions of a younger generation renewed Sickert’s interest in the possibilities for modern art in London. As Baron records, in 1906 he rejoined the NEAC showing his view up into the gods at the Middlesex Music Hall, Noctes Ambrosianae 1906 (fig.1). Sickert’s music hall paintings along with the contre-jour studies of nudes he painted in his new north London studio in Mornington Crescent in 1906–7 were to be especially influential to Gore and the latter, too, to another ex-Slade student, Harold Gilman.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 762 mm

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

Lucien Pissarro 1863–1944

April, Epping 1894

Oil paint on canvas

support: 603 x 730 mm

Tate N04747

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1934

© Tate

Fig.2

Lucien Pissarro

April, Epping 1894

Tate N04747

© Tate

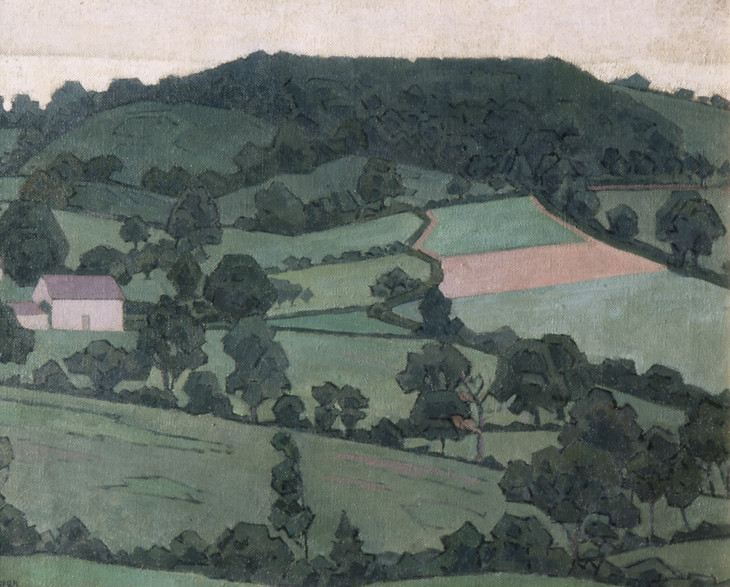

Sickert continued to show in Paris throughout these years, while in London he rapidly established an alternative network to the NEAC. The core membership of the Camden Town Group in fact was to evolve from a coterie of artists who from autumn 1907 were attending informal Saturday afternoon ‘At Home’ receptions for artists, critics and potential buyers at a rented Bloomsbury studio on the first floor of 19 Fitzroy Street, near Sickert’s existing studio at number 8. In addition to Gore and Gilman, what became the Fitzroy Street Group in 1907 was to include the American-born artists Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson, as well as Malcolm Drummond, a Slade student between 1903 and 1907 and, from 1908, one of Sickert’s evening school pupils at Westminster School of Art. Members also included Robert Bevan, who after training at the Académie Julian in Paris in 1890–1 visited Brittany and painted with the Pont-Aven group; Charles Ginner, who moved permanently to London from Paris after meeting Gore and Gilman at the Allied Artists’ Association (AAA) in 1910; and Walter Bayes, briefly a Westminster student whose works were also shown at the AAA.13 The AAA, which was a British version of the French Salon des Indépendants, was set up in 1908 by the art critic Frank Rutter and was open to all, with no jury. Approved by Sickert as a democratic exercise, the AAA held its first exhibition at the Albert Hall displaying over 3,000 works. Another key Fitzroy Street figure was Lucien Pissarro, son of Camille, who had settled in London in 1890 and was the closest in age to Sickert himself, having been included in the final impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1886. Sickert was acquainted already with Lucien, and Spencer Gore rapidly responded to the handling of light and colour in such works as April, Epping 1894 (Tate N04747, fig.2).

At Fitzroy Street, as one of the specially invited buyers, Louis Fergusson, later recalled, ‘There was an appetising smell of tea and pigment as you ascended to a glorious afternoon of pictures and of talk’.14 As with the AAA, Sickert’s ambition was to provide wider professional and exhibition opportunities for younger artists.15 In direct opposition to the common tendency of artists to paint up to a scale suitable for large venues like the Royal Academy, the concern instead was to encourage the production of ‘Little Pictures for Little Patrons’.16 In a letter to Nan Hudson, Sickert spoke of the need to, ‘Accustom people weekly to see work in a different notation from the current English one. Make it clear that we all have work for sale at prices that people of moderate means could afford. (That a picture costs less than a supper at the Savoy.)’17

To extend their public visibility beyond Fitzroy Street, eventual plans for a larger exhibition society were discussed, resulting in the formation of the Camden Town Group one evening over dinner at Gatti’s restaurant in spring 1911, after which Sickert, the ‘grand seigneur’, ‘waved his arm exclaiming “We have just made history”’.18

The Camden Town Group at its inception comprised sixteen members. Gore was elected president and Fitzroy Street frequenter and ex-Académie Julian student James Bolivar Manson was made its secretary. In addition were Sickert himself, Bevan, Drummond, Gilman, Ginner, Pissarro, Bayes, John Doman Turner (a pupil of Spencer Gore), and William Ratcliffe (a designer and wood-engraver who on Gilman’s advice had attended the Slade for a brief period in 1910). Alongside these were the Welsh ex-Slade painters Augustus John and James Dickson Innes who, like the Australian-born British painter Henry Lamb who had trained in Paris at the Académie de la Palette, worked in a decorative, at times symbolist style producing landscapes or romantic scenes of gypsy life that were quite at odds with the character of the works produced by the rest of the group. An initial member, too, was the future vorticist painter Wyndham Lewis, a Slade contemporary of Gore and his companion on a visit to Madrid in 1902. Another was the ex-Slade artist Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot who departed after the group’s first exhibition, to be replaced briefly by the Bloomsbury painter Duncan Grant, friend of Roger Fry and Vanessa Bell. Distinctly absent from membership were any of the women artists closely involved with the wider circle, notably Sands and Hudson as well as Sylvia Gosse, a friend and pupil of Sickert and later collaborator at his Rowlandson House art school. Sickert’s report of the group’s decision in this respect was succinct: ‘There are lots of 2 sex clubs, & several one sex clubs, & this is one of them.’19

Rutherston’s account of Sickert’s dominance underplays the already extensive travels and experience of the younger artists in the new group and their awareness of recent developments in modern European art.20 In the context of observations by the art historian Andrew Stephenson, such accounts can be viewed as a prime example of how the history of modern has been perceived in terms of a lineage of master–pupil relationships.21 A survey of contemporary reviews from the group’s three exhibitions at the Carfax indeed reveals a far less than decisive public view of obvious leadership, with instead a sense that there was no ‘dominating theory to exploit’.22 Pissarro was widely praised in the press for his ‘luminism’ and ‘jewelled impressionism’.23 There was much recognition for John’s two Welsh landscapes at the first exhibition, and Lewis’s semi-abstract Danse at the second was noted for its ‘frank imitation of the cubist conventions, with a touch of Futurist ferocity about the strenuousness of its lines’.24

Press reviews demonstrate much confusion over the distinct character of the group. With memory still of Fry’s, to many, shocking exhibition of works by Gauguin, van Gogh and Cézanne at the Grafton Gallery, Charles Marriott writing in the Evening Standard and St James’s Gazette appeared relieved: ‘About the whole exhibition there is an engaging atmosphere of common-sense.’25 Reassured reviewers were also swift to point out that most of the pictures on display were not of Camden Town, or even of urban themes, and many of the painters had no connection with that ‘peculiarly inartistic’ north London inner suburb.26

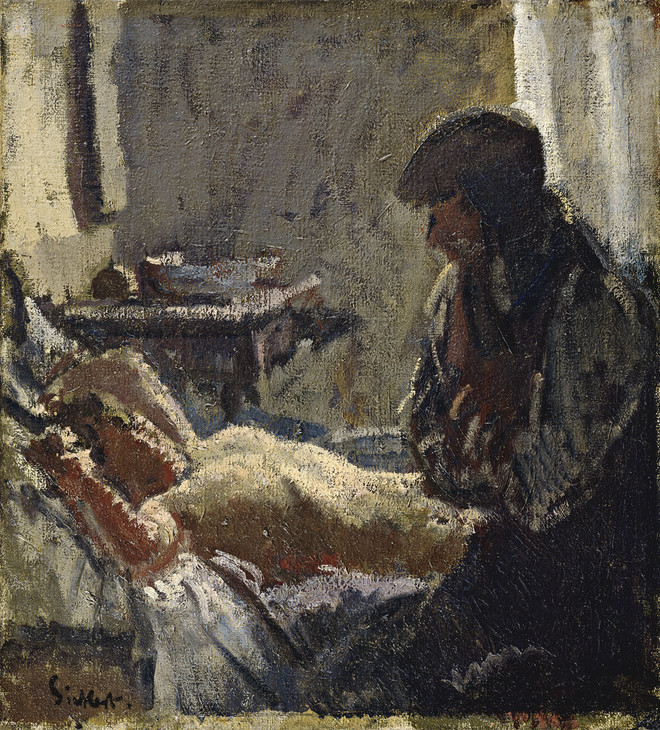

Only Sickert, familiar with the music halls from earlier years, Gore and for a time Gilman lived and regularly painted in the district that gave the group its title, Bayes recalling that, ‘It was Sickert who invented the name Camden Town Group, averring that that district had been so watered with his tears that something important must sooner or later spring from its soil.’27 Stretching from King’s Cross to Hampstead, Camden had been a middle class residential area until the late nineteenth century when, following the construction of new railway lines, once affluent family houses were divided into cheap lodgings for urban workers. A sign of Sickert’s sharp instinct for publicity, the choice of title followed the widely reported murder of part-time prostitute Emily Dimmock in 1907. This was a strategic move to benefit from scandalous associations, and Sickert contributed two works to the first Carfax exhibition entitled The Camden Town Murder Series (figs.3 and 4), one of which was also known as What Shall We Do for the Rent?.28 The origin of the series derived from the artist’s previous studies of prostitutes in Venice, but the group’s title is suggestive too of the wider exoticising fascination from the 1890s with the sordid nature of working class London lives – as dissected in novels such as Arthur Morrison’s Tales of Mean Streets (1894) and Somerset Maugham’s Liza of Lambeth (1897).

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Camden Town Murder c.1907–8

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 406 mm

Daniel Katz Family Trust

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Daniel Katz Family Trust

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

The Camden Town Murder c.1907–8

Daniel Katz Family Trust

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Daniel Katz Family Trust

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Summer Afternoon or What Shall We Do for the Rent? c.1907–9

Oil paint on canvas

515 x 410 mm

Fife Council Libraries & Museums: Kirkcaldy Museum & Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Antonia Reeve

Fig.4

Walter Richard Sickert

Summer Afternoon or What Shall We Do for the Rent? c.1907–9

Fife Council Libraries & Museums: Kirkcaldy Museum & Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Antonia Reeve

Intense and lurid press coverage had followed Dimmock’s murder. As a consequence, as several contemporary reviews reveal, some critics were relatively undisturbed by Sickert’s Camden Town Murder Series. The Commentator, for instance, found them ‘disappointingly unsensational after the columns of the halfpenny press. Our gladiatorialised senses demand much gruesome detail. There is no blood to be seen, and any sense of horror there may be is severely restrained.’29 Several reviewers perceived instead the transformative capacities of the artist’s particular rendering of the scene. Frank Rutter’s journal the Art News could claim therefore that, ‘Mr. Sickert finds in the sordid surroundings of a tawdry tragedy a fascinating problem of colour, design, and suggestion of form. So completely does the artistic presentment of the subject minimize the gruesomeness of the theme chosen that the rhythm of the design and the charm of colour prevents the spectator from feeling any special sense of horror.’30 The artist’s hand, the manipulation of his paint, transforms the literal wretchedness of the scene. In his own art criticism published in the widely circulated New Age, Sickert himself advocated such a strategy, later deeming Spencer Gore ‘A Perfect Modern’ for his ability to bring beauty to everyday scenes of ‘dreariness and hopelessness’; the true artist he perceived as one who ‘can take a piece of flint and wring out of it drops of attar of roses’.31

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Interior with Nude Washing 1907

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 457 mm

Leeds Museums and Galleries (Leeds Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK/The Bridgeman ArtLibrary

Fig.5

Spencer Gore

Interior with Nude Washing 1907

Leeds Museums and Galleries (Leeds Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK/The Bridgeman ArtLibrary

The marked variation in style between the core Camden Town Group painters was already evident from the time of the Fitzroy Street Group. Indeed, as the art historian Wendy Baron has argued, the ‘heyday’ of what could be described as a Camden Town style had passed before the group actually formed.36 Certainly by the third Carfax exhibition in December 1912 the dominant tendencies and divergences were quite clear. Sickert’s paintings remained generally characterised by a low-toned palette accentuated by dabs of white and coloured highlights observed in the shadows and in the play of light in dusty interiors, whereas the younger artists – Gore, Gilman and Ginner in particular – had more readily assimilated the intense colours and decorative, often rhythmic effects of the post-impressionist painters Gauguin, Cézanne and van Gogh. Nevertheless, the group’s continued bond, as noted in the Athenæum that same year, was ‘social, consisting in the common possession, for instance, of a taste for low-class surroundings – for unpretentious subjects, which in no circumstances could yield an imposing exhibition picture’.37

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

St James's Park 1912

Oil paint on canvas

725 x 900 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.6

Malcolm Drummond

St James's Park 1912

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Nude on a Bed c.1911–12

Oil on canvas

614 x 467 mm

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Photo © Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Fig.7

Harold Gilman

Nude on a Bed c.1911–12

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Photo © Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Ennui c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1524 x 1124 mm; frame: 1741 x 1340 x 110 mm

Tate N03846

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

© Tate

Fig.8

Walter Richard Sickert

Ennui c.1914

Tate N03846

© Tate

Yet the second tendency also figures in the painters’ expressions of metropolitan modernity – sites of fashionability, leisure and consumption – as found in Gore’s many depictions of the glittering Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, such as Rule Britannia 1910 (Tate T06521, fig.9), which show the intense colour and light effects of the bizarre ballet and exotic musical acts staged there, or in Ginner’s vibrant depiction of the bustle of encircling traffic and strident advertising in Piccadilly Circus 1912 (Tate T03096, fig.10). In a review of the third Carfax exhibition the Pall Mall Gazette maintained that, ‘Mr. C. Ginner’s “Piccadilly Circus,” both in its crude tones and jumbled composition, happily suggests the noise and confusion of that busy thoroughfare’.39

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Rule Britannia 1910

Oil paint on canvas

unconfirmed: 762 x 635 mm; frame: 970 x 845 x 115 mm

Tate T06521

Presented by the Patrons of British Art through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1992

Fig.9

Spencer Gore

Rule Britannia 1910

Tate T06521

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 813 x 660 mm; frame: 939 x 786 x 65 mm

Tate T03096

Purchased 1980

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.10

Charles Ginner

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Tate T03096

© The estate of Charles Ginner

In contrast to these works, however, Gore’s paintings of suburban parks and gardens, like The Fig Tree 1912 (Tate T00028, fig.11), might be read as scenes of tranquillity, of nature in small pockets. Indeed, Gore’s paintings nuance for us some of the more sharply polarised distinctions between the city and the country inherited from the later nineteenth century and still much in evidence among the nostalgic, melancholic landscapes displayed at Royal Academy exhibitions. Despite the title, landscapes were an important feature at Camden Town Group exhibitions; the third show containing, for example, Gore’s Letchworth Common, Bevan’s A Devonshire Farm and Ginner’s North Devon – the particular semi-rural and rural sites especially favoured by these artists. In Bevan’s landscapes, as in his depictions of London streets and cab-yard scenes, as Frank Rutter later remarked, the artist ‘ever progressed from complexity to simplicity, from a penchant for atmospheric effects to a passion for clean definition and clear-ringing design’ (fig.12).40 Essentially, Camden Town painters provide a modern vision of an ancient landscape.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Fig Tree c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 635 x 760 mm

Tate T00028

Bequeathed by J.W. Freshfield 1955

Fig.11

Spencer Gore

The Fig Tree c.1912

Tate T00028

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

Rosemary, La Vallée 1916

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 493 x 615 mm

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove H1988.14

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Fig.12

Robert Bevan

Rosemary, La Vallée 1916

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove H1988.14

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

As divisions in the London art world increased – fuelled by the appearance of futurism in 1912, the impact of Roger Fry’s second post-impressionist exhibition at the Grafton that October, Rutter’s Post-Impressionist and Futurist show the following October at the Doré Galleries, and the formation of Wyndham Lewis’s Rebel Art Centre, also in 1913 – tensions between members of the group inevitably grew and there was a move to expand, to join with the larger Fitzroy Street circle and to take in a more diverse selection of painters, including women, as well as the sculptors Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Jacob Epstein. By March 1914 the artists were showing at William Marchant’s Goupil Gallery as the renamed London Group, but with the notable absence of both Sickert and Pissarro.41 In the general spirit of the era, smaller groupings emerged too, a ‘Neo-Realist’ manifesto was produced by Ginner and Gilman in early 1914 – resulting in a prickly falling out with Sickert in the columns of the New Age – and the Cumberland Market Group was organised by Bevan in 1914.42 The death of Gore, that most diplomatic and conciliatory of artists, following a bout of pneumonia in spring of that year, provides for us the clearest sense of the formal end of the Camden Town Group, even if key figures were to maintain its principles in their work for some time to come.

Reminiscences appeared at subsequent retrospectives, anniversary and loan exhibitions but the group was rather neglected by scholars following the pioneering studies by Wendy Baron in the 1970s and Simon Watney’s and Charles Harrison’s valuable short surveys in 1980 and 1981.43 That neglect has been largely shaped by art historical over-preoccupation with avant-garde formations. While the importance of Sickert was and is continually recognised, and his relation to Whistler and Degas frequently underlined, the wider circle of Camden Town Group painters has been relatively under-researched; their works often perceived in terms of a belated and derivative post-impressionism or subsumed into conventional categories of ‘Englishness’, often perceived in terms of an eclectic, anti-intellectual conservatism. In this respect a marked interest in frequently uneventful suburban lives, so much a focus of Camden Town paintings, has come to negatively characterise the group itself. By contrast, contemporaries such as artists in the Bloomsbury Group alongside the more overtly radical vorticists and English futurists have clearly dominated influential ‘survey’ histories of early twentieth-century British art.44 Such a view was perpetuated to some degree by the legacy of once significant figures like the British art historian and devotee of Picasso, Douglas Cooper, for whom art in Britain was inevitably measured against a canon of European, most typically Parisian art, and valued as second rate.45

More recent studies, however, have articulated a broader definition of modernism, one not preoccupied with formal innovations beginning with Manet and running through the development of mid-twentieth-century abstraction, but concerned, as David Peters Corbett observes, with the ‘transformations ... in the cities, suburban and sub-rural spaces and the contested areas of representation thrown up by the new conditions of experience in modernity’. This is modernist art responding to modern conditions.46 Others, notably art historian Lisa Tickner, have called for considerations of the ‘local formation of particular modernisms’, giving close attention to the historical specificity of cultural production and consumption. With a reduced focus on universal ‘modernism’ and linear histories, diverse engagements with modernity assume a far greater importance, yielding richer accounts of the complex interrelations between an artist’s works and ‘the technical, social, pictorial, institutional, discursive and autobiographical urges and constraints [which propel and shape] them’.47 Tickner follows Michael Baxandall’s view of fifteenth-century Italy in seeing British paintings between 1860 and 1914 as ‘the deposit of a social relationship’,48 and expands very usefully on the value of the account given by the philosopher and sociologist Pierre Bourdieu of the ‘field of cultural production’, the particular space within which individuals and institutions operate, and the necessary study of the ‘social and psychic formations of subjects’ therein.49

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Nearing Euston Station 1911

Oil on canvas

498 x 600 mm

King’s College, Cambridge, on loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum

Photo © The Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge

Fig.13

Spencer Gore

Nearing Euston Station 1911

King’s College, Cambridge, on loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum

Photo © The Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge

Within the terms outlined in these examples of recent studies, works by members of the Camden Town Group clearly re-emerge as a fascinating area of interest, focusing our attention on the complex evolution of modernism, on questions of group and individual identities, generation and periodisation in an era uneasily located between more conventional perceptions of the late Victorian period and modernism. In the context, as we have seen, of a group of artists who no longer shared common stylistic characteristics by the time they had officially formed, and whose genesis can be traced back to developing tendencies in the 1880s, to specify strict dates for our attention is unhelpful at best. Similarly, to ignore works produced by the women associates who were not actual members is patently ludicrous and would seriously undermine our ability to assess the group’s active role in the construction and contestation of gendered and sexual stereotypes at a time when conventional attitudes were being decisively challenged by Suffrage societies and the emergence of the ‘New’ or modern woman. Renewed attention to women artists like Bevan’s wife Stanislawa de Karlowska and Sickert’s friends Ethel Sands, Nan Hudson and Sylvia Gosse further underlines the complex attitudes and identities within the group itself, as does consideration of relations between, for example, their paintings of interior genre subjects and those by male artists then perceived as more conventional and conservative, like Henry Tonks and Walter Russell.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 406 mm; frame: 808 x 605 x 93 mm

Tate N05317

Purchased 1942

Fig.14

Harold Gilman

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917

Tate N05317

If, fundamentally, there is an underlying ‘problem’ of Camden Town Group painting, it has always been a question of definition. Returning to Samuel Hynes’s identification, it is certainly the case that what unites these painters is their preoccupation with the present, with the direct recording of everyday experience and the specific character of modern life as it evolved and transformed around them. To that extent, the particular type of urban realism that Sickert, his friends and his followers stood for has had an afterlife at various moments throughout the following decades: in the ethos of William Coldstream’s Euston Road School in the 1930s, in the post-war impulse of ‘kitchen-sink’ painters John Bratby and Jack Smith, in the thickly worked surfaces of ‘School of London’ artist Frank Auerbach and, in relation to Sickert in particular, paintings of the nude by both Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon. That legacy has evolved across generations in relation to their unique social and cultural conditions. A final word therefore might go to Ginner writing in the New Age in 1914:

Each age has its landscape, its atmosphere, its cities, its people. Realism, loving Life, loving its Age, interprets its Epoch by extracting from it the very essence of all it contains of great or of weak, of beautiful or of sordid, according to the individual temperament. Realism is thus not only a present intimate revelation of its own time, but becomes a document for future ages. It attaches itself to history.53

Notes

Samuel Hynes, ‘Camden Town and its Literary Context’, Arts Magazine, vol.55, no.1, September 1980, p.133.

For an excellent discussion disputing notions of cultural isolation in this period, see Andrew Stephenson, ‘Edwardian Cosmopolitanism, ca.1901–1912’, in Morna O’Neill and Michael Hatt (eds.), The Edwardian Sense: Art, Design and Performance in Britain, 1901–1910, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2010, pp.251–84.

Walter Sickert, ‘Impressionism’, in A Collection of Paintings by the London Impressionists, exhibition catalogue, Goupil Gallery, London 1889, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.60.

Peter Brooker, Bohemia in London: The Social Scene of Early Modernism, Palgrave Macmillan, London 2007, p.30. Brooker’s focus is on Sickert’s acquaintance, the poet and ‘cosmopolitan wanderer’ Arthur Symons, another devotee of the music halls who claimed that ‘to become modern, poetry must respond to the experience of the city’ (p.29).

Baron’s writings include Sickert, Phaidon, London 1973, Camden Town Recalled, exhibition catalogue, Fine Art Society, London 1976, The Camden Town Group, Scolar Press, London 1979, revised as Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Ashgate, Aldershot 2000, and Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2006.

Walter Sickert, ‘The New Life of Whistler’, Fortnightly Review, December 1908, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.185.

On Sickert’s relationship with Degas, see also Anna Gruetzner Robins and Richard Thomson (eds.), Degas, Sickert and Toulouse-Lautrec, London and Paris, 1870–1910, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2005.

On Sickert and the London Impressionists, see Anna Gruetzner Robins, ‘The London Impressionists at the Goupil Gallery: Modernist Strategies and Modern Life’, in Kenneth McConkey (ed.), Impressionism in Britain, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1995, pp.87–96. Other members of the London Impressionists included Philip Wilson Steer, Sydney Starr, Theodore Roussel and Paul Maitland.

Charles Marriott, Modern Movements in Painting, Chapman and Hall, London 1920; cited in Charles Harrison, English Art and Modernism, 1900–1939, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1994, p.32.

For a recent study of this period, see Robert Upstone, Sickert in Venice, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2009.

Albert Rutherston, ‘From Orpen and Gore to the Camden Town Group’, Burlington Magazine, August 1943, pp.202–5.

Frank Rutter was an influential figure and consistently supported Camden Town Group painting in reviews. He was also author of Revolution in Art in 1910, founder of the Allied Artists’ Association and editor of its publication Art News, and for a time curator of Leeds City Art Gallery, where Gilman and Ginner visited him in April 1912. For further discussion of Rutter, see David Fraser Jenkins, ‘The Response to Camden Town Painting, Then and Now’, in Robert Upstone (ed.), Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008, pp.48–54.

Louis F. Fergusson, ‘Souvenir of Camden Town: A Commemorative Exhibition’, Studio, February 1930, pp.111–19. Other collectors who attended Fitzroy Street gatherings include Judge William Evans, Cyril Butler, Hugh Hammersley and Sir Hugh Lane, all of whom bought from Philip Wilson Steer also.

Although, as Wendy Baron points out, by 1909 the NEAC was becoming increasingly inclusive in its selection processes and Gore, Sickert, Gilman, Pissarro and John were all showing there. For a full account of the evolution of the AAA, Fitzroy Street and Camden Town groups, see her essay ‘Camden Town Recalled’, reproduced at http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/wendy-baron-camden-town-recalled-r1104354 .

Walter Sickert, ‘Little Pictures for Little Patrons’, New Age, 11 August 1910, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.271. See also Wyndham Lewis and Louis F. Fergusson, Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, Chatto & Windus, London 1919, p.19.

Walter Sickert, letter to Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson, 1907, Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.34, quoted in Baron 2000, p.26. On Sickert’s relationship with Sands and Hudson, see Wendy Baron, Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, Peter Owen, London 1977.

Walter Sickert, letter to Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson, June 1911, Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.77, quoted in Baron 2000, p.45.

For Andrew Stephenson’s discussion of this tendency within some of the past scholarship on Sickert, see ‘Buttressing Bohemian Mystiques and Bandaging Masculine Anxieties’, Art History, vol.17, no.2, June 1994, pp.268–78.

The Westminster Gazette’s 6 December 1911 review, opening with ‘There is a group in Camden Town, Of artists brave and free’, asked: ‘what is the bond of union that unites the Group? It cannot be entirely geographical, for we – perhaps wrongly – have rather associated some of the more prominent members with south-western districts’ [i.e. Chelsea]. And the Morning Post (17 December 1912) commented: ‘A few years ago Camden Town was known chiefly as a place through which ‘buses ran to Hampstead and Highgate. Now a group of artists has taken its name, the reasons why we do not know. Judging by their work they might have hidden their identity quite as well under the name of the Clapham, Hoxton, Kensington Group.’

For further detailed studies of the development of the Camden Town Murder Series, see Anna Greutzner Robins, Walter Sickert: Drawings, Scolar Press, Aldershot 1996 and Lisa Tickner, ‘Walter Sickert: The Camden Town Murder and Tabloid Crime’, Modern Life & Modern Subjects: British Art in the Early Twentieth Century, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2000, pp.11–47, reproduced at http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/lisa-tickner-walter-sickert-the-camden-town-murder-and-tabloid-crime-r1104355 .

See Baron, ‘Camden Town Recalled’, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/wendy-baron-camden-town-recalled-r1104354 .

Frank Rutter, ‘The Art of Robert P. Bevan’, Studio, vol.91, 1926, p.112. For Rutter, Bevan therefore typified the trend of European painting ‘as it passed out of the nineteenth into the twentieth century’.

For a detailed account of the formation of the London Group, see Malcolm Easton, ‘The Camden Town Group into the London Group: Some Intimate Glimpses of the Transition 1911–14’, Art in Britain 1890–1940, exhibition catalogue, University of Hull 1967, pp.60–75, reproduced at http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/malcolm-easton-the-camden-town-group-into-the-london-group-some-intimate-glimpses-of-the-r1104360 , and Baron 1979, pp.55–62.

For discussion of these emerging groups and the rivalry between them, see Simon Watney, English Post-Impressionism, Cassell, London 1980.

See Baron, ‘Camden Town Recalled’, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/wendy-baron-camden-town-recalled-r1104354 . See also the important earlier overview by Malcolm Easton, ‘The Camden Town Group into the London Group: Some Intimate Glimpses of the Transition 1911–14’, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/malcolm-easton-the-camden-town-group-into-the-london-group-some-intimate-glimpses-of-the-r1104360 . Charles Harrison surveyed the group in English Art and Modernism, 1900–1939, Yale University Press, London and New Haven 1981. See also Watney’s account in English Post-Impressionism. For full references to the scholarship on Sickert and the Camden Town Group see the bibliography .

For an interesting discussion of what he perceives as the important continuities rather than ruptures between the Camden Town Group and Wyndham Lewis’s engagement with modernity, see the final chapter of David Peters Corbett’s The World in Paint: Modern Art and Visuality in England 1848–1914, Manchester University Press, Manchester 2004, pp.215–60.

Cooper’s views appeared, for example, in his 1954 Courtauld Collection. They were more widely aired in his dispute in the late 1940s and 1950s with then Tate Gallery director John Rothenstein over the latter’s attempts to build up the British collection at Tate. See Rothenstein’s Brave Day; Hideous Night, vol.2, Hamish Hamilton, London 1966, pp.289–91. For a far more reasoned but still largely hostile view of early twentieth-century British art and associations of ‘Englishness’, see Charles Harrison, ‘“Englishness” and “Modernism” Revisited’, Modernism/Modernity, vol.6, no.1, 1999, pp.75–90.

Introduction to David Peters Corbett and Lara Perry (eds.), English Art 1860–1814: Modern Artists and Identity, Manchester University Press, Manchester 2000, p.2.

Ibid. The reference is to Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1972.

Academic and public awareness of this field was boosted by the survey exhibition held at Tate Britain in 2008, Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, curated by Robert Upstone. This was the first chance to see works by the group brought together for two generations. As well as Robert Upstone, the exhibition catalogue includes contributions from Wendy Baron, Richard Humphreys, David Fraser Jenkins, John Lessore, Nicola Moorby, Lynda Nead, Richard Shone, Matthew Sturgis and a keynote essay by David Peters Corbett.

An excellent example of a study of this kind is Lisa Tickner’s ‘Walter Sickert: The Camden Town Murder and Tabloid Crime’, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/wendy-baron-camden-town-recalled-r1104354 .

Ysanne Holt is Reader in Art History at the University of Northumbria and Academic Advisor to The Camden Town Group in Context.

How to cite

Ysanne Holt, ‘The Camden Town Group: Then and Now’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www