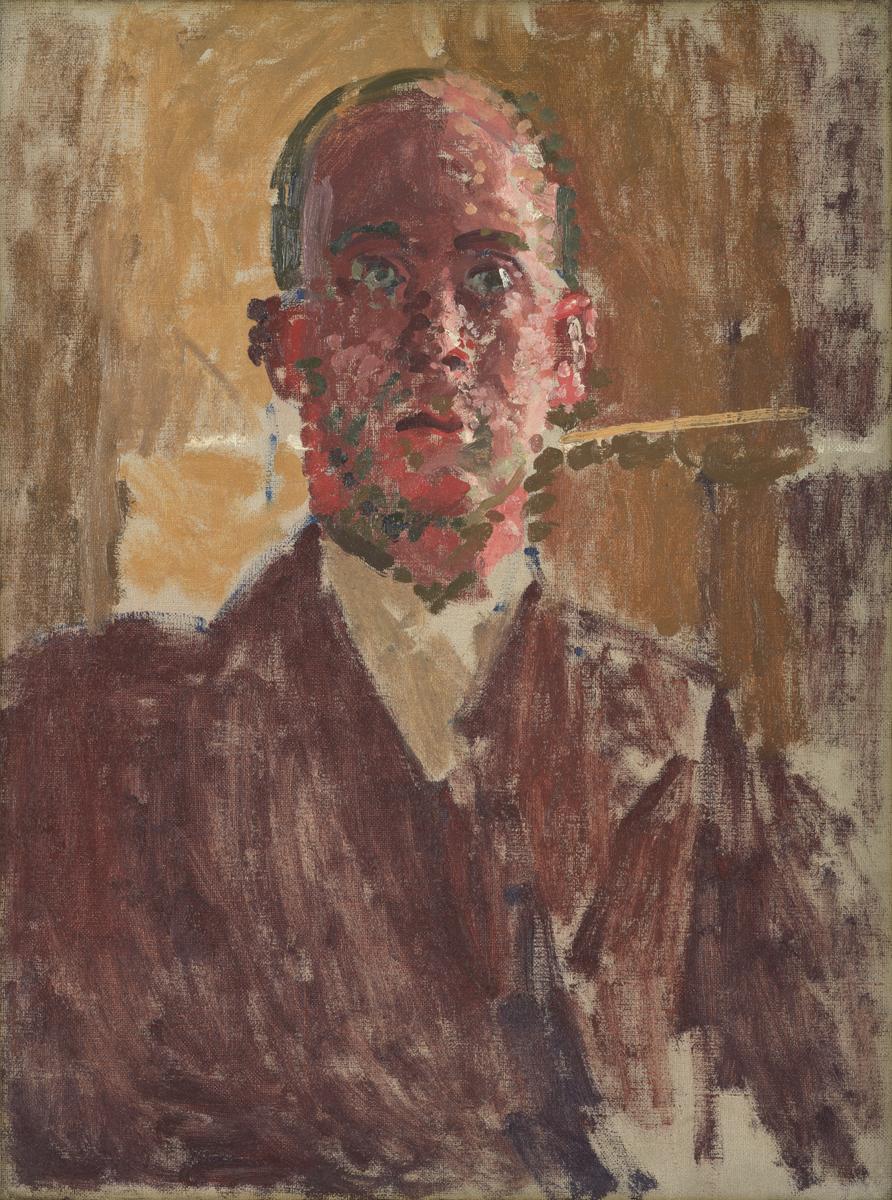

Walter Richard Sickert Harold Gilman c.1912

Walter Richard Sickert,

Harold Gilman

c.1912

This portrait of Harold Gilman was probably painted in Walter Sickert’s Fitzroy Street studio. Gilman’s jacket is rendered in thin, rusty coloured strokes, which contrast with the bright spots and dashes of pinks, whites and blacks that capture the almost visionary expression of the face. The use of dark browns and blacks might have irritated or amused Gilman, whose style strayed from Sickert’s influence, eventually causing the two to fall out.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Harold Gilman

c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 457 mm

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1957

T00164

c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 457 mm

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1957

T00164

Ownership history

Purchased from Mrs Sylvia Gilman, the sitter’s widow, by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest and presented to Tate Gallery 1957.

Exhibition history

1950

Camden Town Group, Alex Reid and Lefevre, London, November 1950 (45).

1951

The Camden Town Group: Festival of Britain Exhibition, by Arrangement with the Arts Council of Great Britain, Southampton Art Gallery, June–July 1951 (115, reproduced).

1953

Paintings and Drawings by Walter Sickert, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, January 1953 (24, as ‘Portrait of Harold Gilman’).

1953

The Camden Town Group, Arts Council, London 1953 (41).

1956–7

British Portraits, Royal Academy, London, Winter 1956–7 (804).

1958

One Hundred and Nineteenth Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts, Royal Academy, London, May–August 1958 (78).

1965

Decade 1910–20, (Arts Council tour), City Art Gallery, Leeds, May 1965, Art Gallery, Reading, May–June 1965, City Art Gallery, Manchester, July 1965, Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, July–August 1965, Museum and Art Gallery, Leicester, September 1965 (29).

1976

Camden Town Recalled, Fine Art Society, London, October–November 1976, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, November–December 1976 (147, reproduced).

1980

The Camden Town Group, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, April–June 1980 (86, reproduced).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (10, reproduced).

1996–7

Characters and Conversations: British Art 1900–1930, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1996–April 1997 (35, reproduced).

1998

Two British Impressionists: Walter Sickert and Philip Wilson Steer, Norwich Castle Museum, January–April 1998 (24, reproduced).

2004

Walter Richard Sickert: The Human Canvas, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, July–October 2004 (23, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (7, reproduced).

References

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, p.101.

1964

Cambridge Opinion, vol.37, January 1964, reproduced p.5.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.639.

1971

Marjorie Lilly, Sickert: The Painter and his Circle, London 1971, pp.31, 54, reproduced pl.12.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London 1973, pp.117, 354, no.299, reproduced pl.207.

1974

Charles Harrison, ‘The Origins of Modernism in England’, Studio International, vol.88, no.969, September 1974, reproduced p.77.

1976

Denys Sutton, Walter Sickert: A Biography, London 1976, reproduced fig.30.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.108, 390, reproduced p.109 and frontispiece.

1980

Simon Watney, English Post-Impressionism, London 1980, p.58, reproduced fig.39.

1992

Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, p.174.

1994

Charles Harrison, English Art and Modernism 1900–1939, New Haven and London 1994, reproduced fig.10.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.205.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.385, reproduced.

Technique and condition

Sickert purchased a pre-primed canvas from the artists’ colourman John B. Smith, who had premises close to Sickert’s studio on Hampstead Road, NW1. He chose a fine tightly woven canvas prepared with sizing and thin off-white priming, providing a finely grained preparatory surface. The artist appears to have brushed a further layer of thinned grey paint onto the ground to form a cold grey ‘imprimatura’ or priming. He may have executed the work truly alla prima, in one sitting (see also Tate N03182): it exhibits some wet-in-wet mixing in the impasto and appears to have been painted quickly, with little preparation, in the manner of an oil sketch painted from life, with brush hairs caught in the paint where he worked most vigorously.

Sickert established the portrait drawing roughly in paint and then coarsely brushed in browns and ochres with a 4 mm hogshair brush to block in the body, background and shadows on the face. By not painting up to the colour boundaries he left significant areas of the imprimatura exposed throughout the composition. He painted the face in an impressionist technique using a loaded brush with little further working or modification of the paint, creating thick raised impasto with dabs of colour in red, pink and green forming peaks up to 2 mm high on the face. Sickert left it unvarnished in the dusty studio for some time, where the paint absorbed dust as it dried. He may never have intended to varnish it, although a thin layer was at some time applied, perhaps by a dealer.

Stephen Hackney

July 2004

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', July 2004, in Robert Upstone, ‘Harold Gilman c.1912 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

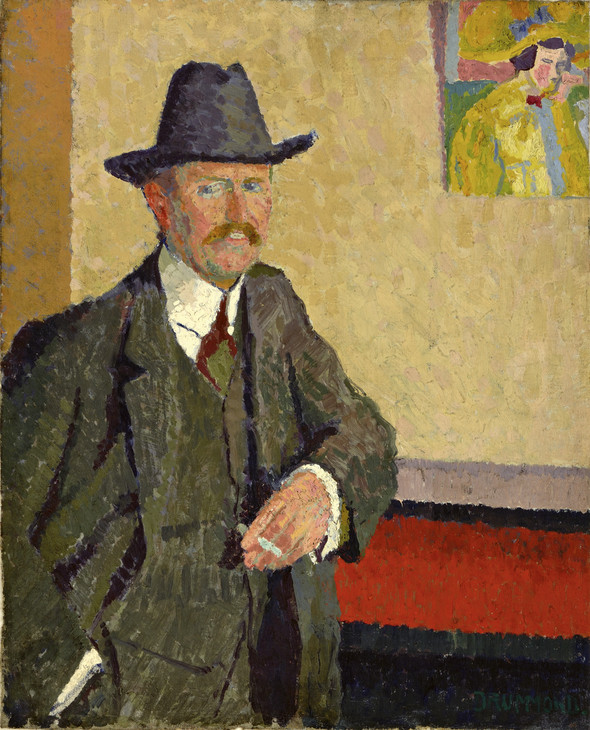

The Camden Town Group made a small but distinguished number of self-portraits and portraits of one another. Malcolm Drummond’s oil of Ginner c.1911 (fig.1) was included in the second Camden Town Group exhibition in December 1911 (41), and Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman both painted portraits of Stanislawa de Karlowska, Robert Bevan’s wife. Drummond also painted the famous group portrait of J.B. Manson, Gore and Charles Ginner considering a painting in 19 Fitzroy Street c.1913–14 (fig.2). Such activities imply a strong sense of self-identity among the group, and to a certain degree a shared desire to monumentalise its principles. In this they recall other artist groups who commemorated themselves, notably the Nazarenes and the Pre-Raphaelites. But portraiture, albeit of a naturalistic, informal, uncommissioned kind, was a recurrent activity in Camden Town painting. Gore painted numerous pictures of his wife (see Tate T03561); Gilman painted a number of his female friends, and notably the sequence of pictures of his landlady Mrs Mounter (see Tate N05317); and Sickert’s arrangements of Hubby and Marie might also be thought of as a kind of assumed domestic portraiture (see Tate N03846).

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

Charles Ginner 1911

Oil paint on canvas

603 x 490 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.1

Malcolm Drummond

Charles Ginner 1911

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Malcom Drummond 1880–1945

19 Fitzroy Street c.1913–14

Oil paint on canvas

710 x 508 mm

Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

Fig.2

Malcom Drummond

19 Fitzroy Street c.1913–14

Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

Sickert painted this portrait of Gilman and presented it to him as a gift. Sylvia Gilman, the artist’s second wife, wrote in a letter to the Tate Gallery in 1958:

The Sickert portrait of Harold Gilman was painted about 1912 – the picture to my knowledge was not exhibited ... As it was given to my husband when finished I do not think that Sickert would have shown it, & I am sure that my late husband would not have done so. I remember being told it was painted at Sickert’s Fitzroy St studio.1

If the portrait was done in 1912, it would have had to be made in the first half of the year, as Gilman was away in Sweden from August to November 1912. This was a difficult time for Gilman as his marriage had broken down and his wife had taken their children away to America. Sickert has painted the image extremely freely, the background and body sketched in thinly with a harmony of browns, beige and black. Gilman’s face has been rendered with broken touches of pure colour, spots and dashes of beige, brown, pink and black spots. There was tension between Sickert and Gilman over their different tastes in colour and it is characteristic of Sickert’s sense of humour that the portrait is dominated by the ‘impure spots’ of black and brown that would irritate or amuse his subject. Looking far into the distance with open, clear eyes, his face and figure rapt and still, Gilman seems to have the character of a visionary.

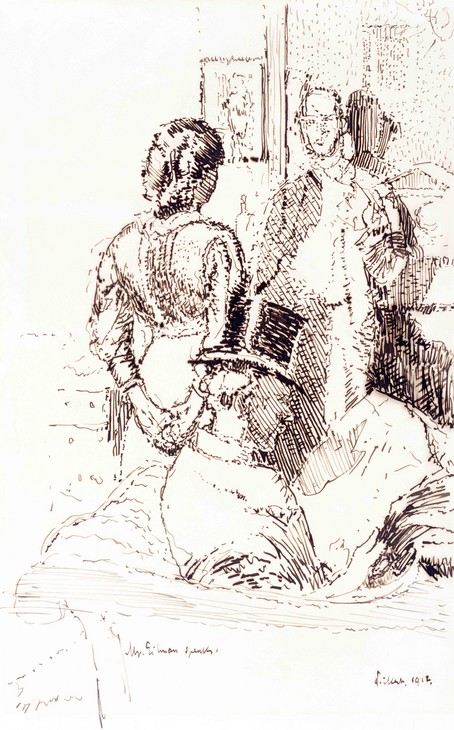

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Mr Gilman Speaks 1912

Ink on paper

305 x 197 mm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

Mr Gilman Speaks 1912

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Sickert made this portrait of Gilman while the two men were still on friendly terms and the Camden Town Group was still in existence, before it dissolved into the London Group. Unfortunately, the making and gift of the portrait probably marked a high point in Sickert and Gilman’s relationship. The London Group was formed in November 1913, with Gilman as its first president, and became an amalgam of the sculptors Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Wyndham Lewis and the vorticists and futurists, and members of the Camden Town Group. They first exhibited together in Brighton in November 1913.4 Although Sickert showed in the exhibition, and gave the opening address, he resigned from the London Group in January 1914, in protest at the work of Lewis and Epstein, considering the latter’s pornographic.5 Sickert and Gilman subsequently quarrelled in 1915 when Sickert, having surrendered his teaching job at Westminster School of Art, reclaimed it, forcing Gilman from the position. Sickert considered Gilman a bad influence on the Westminster pupils because of his support of both the London Group and the brilliant colours of post-impressionism. Gilman was always extremely short of funds, so losing the income from this teaching post was a bitter blow; Sickert was subsequently held in disregard by a number of people in their circle.

However, by this time Gilman and Sickert were already out of sympathy with each other. The accepted contemporary belief was that Sickert’s reclamation of his post was a further sally in a row that had broken out in 1914 over Gilman’s bright palette, pure colour and rough facture, none of which were to Sickert’s taste. Wyndham Lewis wrote:

After [Gilman’s] break of what was more or less discipleship with Walter Sickert and his plunge into the Signac palette and a brighter scheme of things (with a certain amount of noise for such a quiet man), bitumen was anathema for him, and Sickert was bitumen. Sickert’s obstinacy in not adopting the Signac palette he admitted was a source of great perplexity to him. He would look over in the direction of Sickert’s studio, and a slight shudder would convulse him as he thought of the little brown worm of paint that was possibly, even at that moment, wriggling out onto the palette that held no golden chromes, emerald greens, vermilions, only, as it, of course, should do. Sickert’s commerce with these condemned browns was as compromising as intercourse with a proscribed vagrant ... bitumenous [sic] painting, dirty painting, was the mark of the devil ... Mr Sickert’s paintings of Camden Town atrocities, in shuttered rooms, of Gilman himself, built up in, alas, impure spots, his picturesque houses in Dieppe, not so brightly coloured as Gilman would have wished, he shook his head over! But he always retained a great respect for the virtues of his first real master.6

In June 1914 relations between the two declined sharply after Sickert reviewed the New English Art Club exhibition in the New Age. Ignoring Gilman and Ginner totally, Sickert praised Henry Lamb lavishly as a painter who did not lean towards certain artistic practices:

He has never been, for a moment, the dupe of technical pedantries. He knows, for instance, that it is a trivial thing to spend a life-time in an effort after intrinsic brightness of paint. He knows that the brightest colours will fade. He knows that there is a strict limit to the advantages of impasto. He knows that, firstly, excessive impasto is not even durable. He knows that impasto is not in itself a sign of virility. Intentional and rugged impasto ... is a manner of shouting and gesticulating and does not make for expressiveness or lucidity.7

With justification, Gilman felt this was a thinly veiled criticism of his and Ginner’s work. Sickert’s claim that heavy impasto was ‘not even durable’ and that the colours faded struck deeply at Gilman’s ability to sell his work, implying to potential buyers that his paintings would degrade. The next issue of the New Age printed Gilman’s letter of complaint, under the headline ‘The Worst Critic in London’, although this is likely to have been phrased by the journal rather than Gilman. ‘In making a catalogue of all the things that Mr Lamb knows,’ Gilman wrote,

tending to show that that gentleman is not an idiot, seems to imply that there is someone – presumably exhibiting at the NEAC – who does not know those things ... I am not acquainted with any man who thinks there is any merit in thick paint for the sake of thick paint. Mr Sickert has himself painted in both thick and thin paint. This violent paragraph of his may be merely his way of expressing his preference for thin. He will be painting in thick paint in six months. It is in any case, a technical detail, and depends on the questions of brilliance, permanence, covering power, deliberateness of workmanship, etc., impossible to discuss here ... I wonder if this row of teachers of Art is set up by Mr Sickert to be an easier mark for his inevitable cockshies at any society from which he has retired.8

Charles Ginner expressed himself more succinctly, in a letter printed below Gilman’s:

Sir, Paint is thicker than turpentine. In answer to Mr Sickert I have but one statement to make: I shall paint as thick as I damn well please.9

Sickert’s riposte was to imply in a further piece that Gilman and Ginner were pricked by not being mentioned in his NEAC review, and the article was titled, ‘The Thickest Painters in London’, a double-entendre quite clearly intended to heap mockery upon them. ‘They talk a good deal about Cézanne,’ Sickert wrote patronisingly,

I admire what is good in Cézanne perhaps as much as they do. But I think I have looked at him more carefully ...Will they not look at the Gores in the New English Art Club and say whether that skilful, delicate, draughtsmanlike, reticent use of thick paint, that eloquent variety of touch, is not an ideal technique?10

Sickert caused considerable ill feeling in this attack on his former Camden Town colleagues, and others of the circle such as Harold Harrison of Applehayes,11 Hugh Blaker12 and Douglas Fox Pitt wrote in to the New Age. ‘I feel sure Mr Sickert will not be hurt,’ Fox Pitt wrote, ‘when I say that posterity will know him as a great painter and not as an art critic ... People of taste will always be thankful to Mr Sickert for having founded the Camden Town group.’13

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Frank Rutter, ‘The Work of Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore. A Definitive Survey’, Studio, vol.101, no.456, March 1931, p.207.

Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others, Public Art Galleries, Brighton, December 1913–January 1914.

Walter Sickert, ‘The New English Art Club’, New Age, 4 June 1912, p.115, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, pp.374–5.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Charles Ginner, ‘Letters to the Editor. Mr. Sickert and Mr. Poussin’ The New Age, 7 May 1914, p.23.

- Harold Gilman, ‘Letters to the Editor. The Worst Critic in London’ The New Age, 11 June 1914, p.143.

- Harold Gilman, ‘Letters to the Editor. “Sickert and Neo-Realism.”’ The New Age, 25 June 1914, pp.190–1.

- Wyndham Lewis, ‘Harold Gilman’ Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, Chatto & Windus, London 1919, pp.11–15.

- Charles Ginner, ‘Neo-Realism’ The New Age, 1 January 1914, pp.271–2.

- Charles Ginner, ‘Letters to the Editor. Art and Criticism’ The New Age, 11 June 1914, p.143.

- Walter Richard Sickert, ‘Mr. Ginner’s Preface’ The New Age, 30 April 1914, pp.819–20.

- Walter Richard Sickert, ‘The New English Art Club’ New Age, 4 June 1914, pp.114–15.

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Harold Gilman c.1912 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www