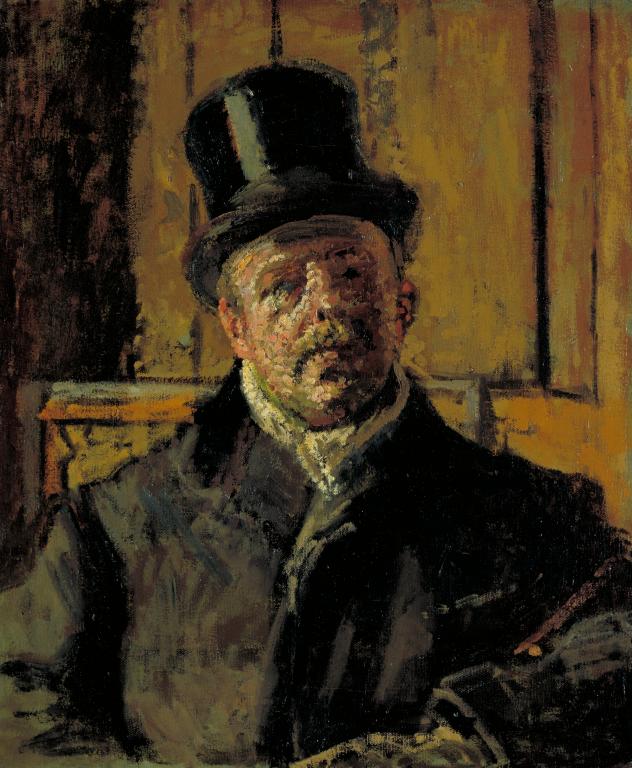

Walter Richard Sickert Jacques-Emile Blanche c.1910

Walter Richard Sickert,

Jacques-Emile Blanche

c.1910

In 1885 Walter Sickert met the French painter Jacques-Émile Blanche, whose patronage and social influence contributed to his early successes. Rendered in a pointillist manner, Blanche’s facial features contrast with the depiction of the smooth, dark fabric of his overcoat. The back of a stretched canvas is visible leaning against a wall in the background, which, together with his slightly tipped hat, evokes a bohemian unconventionality.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Jacques-Émile Blanche

c.1910

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 508 mm

Purchased (Clarke Fund) 1938

N04912

c.1910

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 508 mm

Purchased (Clarke Fund) 1938

N04912

Ownership history

Acquired from the artist by Miss Hilda Trevelyan, from whom purchased by Tate Gallery 1938.

Exhibition history

1912

Forty-Seventh Exhibition of Modern Pictures by the New English Art Club, Royal Society of British Artists, London, May–June 1912 (163, as ‘Portrait of Mr. Jacques Blanche’).

1944–5

Camden Town Group, (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts tour), Wakefield Museum and Art Gallery, July 1944, Jordans School, Chalfont St Giles, August 1944, Ferens Art Gallery, Hull, August–September 1944, Shipley Art Gallery, Gateshead, September–October 1944, Atkinson Art Gallery, Southport, October–November 1944, Reading Museum and Art Gallery, December 1944, Hanley Public Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke on Trent, January–February 1945 (36).

1953

Paintings and Drawings by Walter Sickert, Scottish Committee of the Arts Council, Diploma Galleries, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, January 1953 (53).

1968

Fifth Adelaide Festival of Arts: Walter Sickert, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide 1968 (39).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (20, reproduced).

1992

The Dieppe Connection: The Town and its Artists from Turner to Braque, Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, May–June 1992 (79, reproduced).

1996–7

Characters and Conversations: British Art 1900–1930, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1996–April 1997 (32, reproduced).

2004

Walter Richard Sickert: The Human Canvas, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, July–October 2004 (22, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, February–May 2008 (40, reproduced).

References

1937

Jacques-Émile Blanche, Portraits of a Lifetime, 1937, reproduced opposite p.117.

1941

Robert Emmons, The Life and Opinions of Walter Richard Sickert, London 1941, pp.128, 139.

1943

Lillian Browse and Reginald Howard Wilenski, Sickert, London 1943, pp.13, 51, reproduced pl.36.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, p.101.

1960

Wendy Dimson, ‘Four Sickert Exhibitions’, Burlington Magazine, vol.102, no.691, October 1960, pp.442–3.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.627.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, pp.117, 353, no.294, reproduced pl.204.

1976

Denys Sutton, Walter Sickert: A Biography, London 1976, p.138, reproduced fig.12.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, p.390.

1992

Maureen Connett, Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group, Newton Abbott 1992, reproduced p.25.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.205.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.269, reproduced.

Technique and condition

Jacques-Émile Blanche is painted on a relatively coarse canvas that was purchased in France. The canvas has been stretched by the artist onto a four-member stretcher with the stretcher back to front. It may have been sized but appears to have no commercial priming. Instead, Sickert has applied at least two layers of dull grey oil paint, consisting of lead white, chalk and bone black, across the front surface of the canvas to act as an optical ground. There is no visible evidence of drawing. The composition is brushed in black paint and toned with reds, blacks, browns and greys, and then details were applied with thicker impasto by dabbing the paint onto the canvas with a loaded brush. Sickert then brushed broken dabs and broader strokes of paint to depict impressions of the forms. Strong orange and reds are evident with some green, but otherwise blacks and greys dominate and the general tones of the colours are lowered by painting over a grey ground. The artist’s palette contained Indian red, Mars brown, a yellow, lead white, bone black and ultramarine and the complex mix of pigments suggests considerable mixing on the palette before painting. The painting is varnished, but this appears to have been applied later since it has penetrated cracks to the reverse of the canvas; it is not known whether an earlier varnish was originally applied by the artist.

Stephen Hackney

June 2004

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', June 2004, in Robert Upstone, ‘Jacques-Émile Blanche c.1910 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Born in Paris, the son of a society neurologist, Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861–1942) was a French painter of portraits and landscapes. He enjoyed fashionable success during his lifetime. From 1884 he visited England almost every year, where he regularly submitted work for exhibition. Blanche’s parents kept a house at Dieppe which was a centre for the town’s social scene, as was Blanche’s studio there at Le Bas Fort Blanc. In Dieppe in the mid-1880s Blanche encountered a cross-section of artists and cultural critics, including George Moore, Arthur Symons, Aubrey Beardsley and Charles Conder, as well as Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Paul Helleu and André Gide.1 When he visited Dieppe in 1885 Walter Sickert visited Blanche, although it seems likely they had met for the first time earlier the same year in London. Blanche’s memoirs suggest this first meeting took place when he visited his friend, Mrs Edwin Edwards, who with her husband was on friendly terms with the painter Henri Fantin-Latour. Sickert had been dispatched there by Whistler to try to persuade Fantin-Latour to visit the American artist’s studio.2 It was in Blanche’s Dieppe house in 1885 that Sickert refreshed his acquaintance with Degas.3

Sickert and Blanche became close friends at this time, and the art historian Wendy Baron has written:

The significance of the role played by Jacques-Émile Blanche in Sickert’s life can hardly be stressed too strongly. Sickert himself treated Blanche rather casually in later life. Their friendship cooled towards the end of the first decade of the twentieth century when Sickert gradually dismissed Blanche as a fussy, rather gloomy and lightweight personality. This change of attitude was typical ... and did not do justice to Blanche’s gifts nor to the help he had given Sickert in his early years.4

In 1909 Sickert wrote to Mrs Hammersley, the wife of one of his patrons, making plain his feelings about Blanche:

You may not, probably do not know that in a sense I have treated Blanche who is a very old friend very badly ... The peculiar angle of his somewhat gossipy mind, and ... pushing character of his art politics, which happen to be diametrically opposed to mine decided me that it was absolutely necessary for my peace & comfort to avoid him & his friends as much as I could. He is a little too officious, kindly officious, but too inconvenient & too compromising. Fortunately the reality of my incessant occupation has enabled me to avoid many people I used constantly to see, without apparent unkindness ... I have even written displeasing things about Blanche’s work in my articles.5

But Blanche appears to have been central to Sickert’s early success. He used his influence with the Paris dealers Durand-Ruel and Bernheim-Jeune to get them to exhibit Sickert’s work, and obtained commissions for him from private clients and election to the Salon d’Automne. He purchased a large number of Sickert’s paintings himself, far more than any other single owner, and through such generosity was evidently deliberately subsidising his friend. Many of these pictures were given away to friends, and the large number remaining was bequeathed to the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rouen.6

Blanche painted Sickert a number of times, notably the picture from 1898 that is in the National Portrait Gallery.7 The Tate portrait of Blanche, however, appears to be the only painting Sickert made of his friend, although he made a pen and ink drawing in 1890 that was published in the Whirlwind.8 According to Sickert’s student and biographer Robert Emmons, the Tate portrait was painted at Rowlandson House which Sickert rented in about 1910 (see Tate N05088).9 However, when it was reproduced in Blanche’s autobiography Portraits of a Lifetime (1937), he himself gave it the date 1906, which would preclude it from having been made in Rowlandson House. That it was painted in a studio is confirmed by the presence of a stretched canvas, with its back facing outwards, glimpsed behind Blanche’s shoulders. Blanche may perhaps have misremembered the date, but it has also been said that the portrait was made to celebrate his election to a gentlemen’s club in St James’s.10

Blanche painted Sickert a number of times, notably the picture from 1898 that is in the National Portrait Gallery.7 The Tate portrait of Blanche, however, appears to be the only painting Sickert made of his friend, although he made a pen and ink drawing in 1890 that was published in the Whirlwind.8 According to Sickert’s student and biographer Robert Emmons, the Tate portrait was painted at Rowlandson House which Sickert rented in about 1910 (see Tate N05088).9 However, when it was reproduced in Blanche’s autobiography Portraits of a Lifetime (1937), he himself gave it the date 1906, which would preclude it from having been made in Rowlandson House. That it was painted in a studio is confirmed by the presence of a stretched canvas, with its back facing outwards, glimpsed behind Blanche’s shoulders. Blanche may perhaps have misremembered the date, but it has also been said that the portrait was made to celebrate his election to a gentlemen’s club in St James’s.10

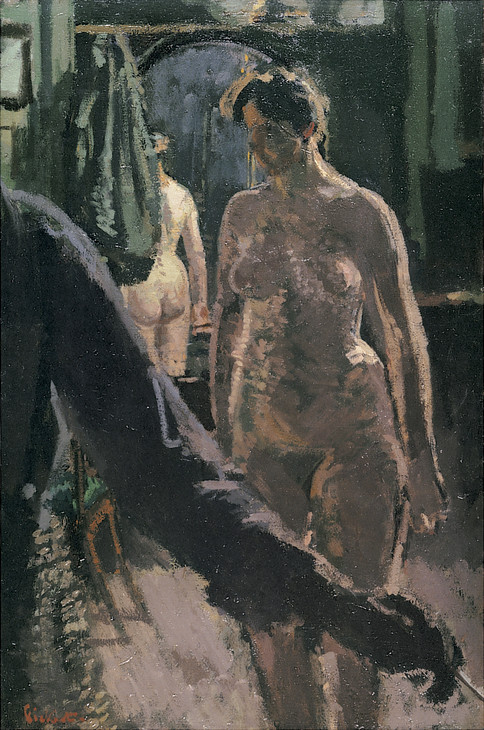

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Studio: The Painting of a Nude 1906

Oil paint on canvas

750 x 495 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Courtesy of Browse & Darby

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

The Studio: The Painting of a Nude 1906

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Courtesy of Browse & Darby

With its Whistlerian lack of foreground and placing of the figure against a wall Sickert creates a very direct confrontation with the sitter. Blanche immediately becomes part of the viewer’s space, and there is no recession or perspective in the composition. His dress is that of a gentleman about town – the combination of overcoat, white scarf and silk hat denoting a man of social standing and position. Like Sickert, Blanche enjoyed the creativity or dandyism that different clothing allowed. Here his conservative costume is partly an assertion that the painter is suited to the higher echelons of social position, but this was of course the position Blanche actually held. His father, Émile, was a noted and fashionable neural specialist, whose large clinic and grounds at Auteuil were painted by Sickert as L’Hotel de Lamballe, La Maison de Dr Blanche (private collection).12 However, Blanche’s wearing of a hat indoors, tipped back slightly on his head, strikes a note of bohemian unconventionality, at odds with the conservatism of the portrait’s ‘head and shoulders’ format.

The first owner of the portrait was Hildegard ‘Hilda’ Trevelyan (died 1948), daughter of the baronet Sir Alfred William Trevelyan of Nettlecombe, a descendent of the nineteenth-century historian George Trevelyan. An amateur painter, she was a close friend of Blanche, and also of Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson, and through them would have been on familiar terms with Sickert.13

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Jacques-Émile Blanche, Portraits of a Lifetime, London 1937, p.45; Wendy Baron, Sickert, London 1973, pp.16, 20 n.4; Tate has in its collection Fantin-Latour’s Portrait of Mr and Mrs Edwin Edwards 1875 (Tate N01952).

Walter Sickert, letter to Mrs Hamersley, 1909; quoted in Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.269.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Jacques-Émile Blanche c.1910 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www