Sylvia Gosse Walter Richard Sickert 1923-5

© The estate of Laura Sylvia Gosse. All Rights Reserved 2023 / Bridgeman Images

Sylvia Gosse,

Walter Richard Sickert

1923-5

© The estate of Laura Sylvia Gosse. All Rights Reserved 2023 / Bridgeman Images

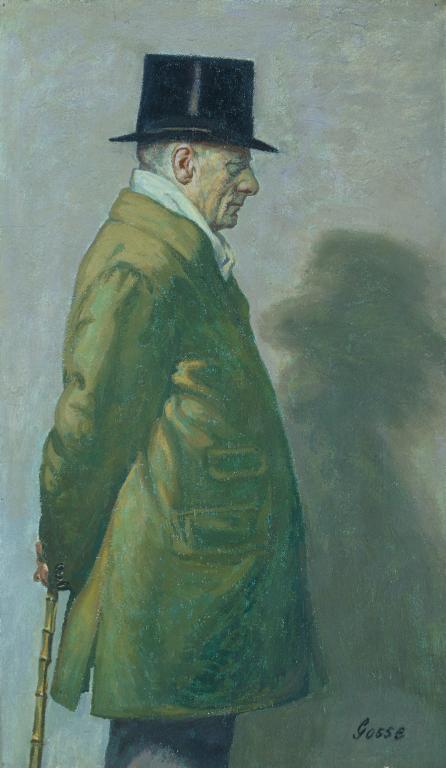

Sylvia Gosse’s three-quarter-length profile portrait of a distinguished Walter Sickert was painted from a photograph, taken in Edinburgh in 1923. A devoted friend of Sickert, and over twenty years his junior, Gosse cared for and supported the elder artist in his later years. Gosse’s use of a photographic source for this painting pre-dates Sickert’s own adoption of the practice by several years.

Sylvia Gosse 1881–1968

Walter Richard Sickert

1923–5

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 305 mm

Inscribed by the artist in black paint ‘Gosse’ bottom right

Presented anonymously 1927

N04364

1923–5

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 305 mm

Inscribed by the artist in black paint ‘Gosse’ bottom right

Presented anonymously 1927

N04364

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist by ?Siegfried Sassoon through the Goupil Gallery, London, March 1925, and presented anonymously to Tate Gallery 1927.

Exhibition history

1925

Recent Paintings by Sylvia Gosse, A.R.E., Goupil Gallery, London, March–April 1925 (12, as ‘Portrait’).

1927

Exhibition of Paintings by Sylvia Gosse A.R.E., Arthur Tooth & Sons Gallery, London, November 1927 (3, as ‘Mr. Richard Sickert’).

1978

Sylvia Gosse: Painter and Etcher 1881–1968, Hastings Museum and Art Gallery, May–July 1978 (15, as ‘Portrait of W.R. Sickert’).

1996–7

Characters and Conversations: British Art 1900–1930, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1996–April 1997 (13, reproduced).

References

1927

Manchester Evening News, 13 December 1927.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, pp.250–1.

1975

Kathleen Fisher, Conversations with Sylvia: Sylvia Gosse, Painter 1881–1968, London and Edinburgh 1975, p.141.

1985

Anne Thwaite, Edmund Gosse: A Literary Landscape 1849–1928, Oxford and New York 1985, p.369.

2004

Alicia Foster, Tate Women Artists, London 2004, p.109, reproduced.

Technique and condition

Walter Richard Sickert is painted in artists’ oil paints on a primed, stretched canvas prepared by the artists’ colourmen John B. Smith, who had premises on the Hampstead Road and was used by a number of Camden Town Group artists. The canvas is one piece of primed, plain-weave linen attached to a four-member pine stretcher with rusted, steel tacks in their original positions. The colourmen’s priming appears to consist of an animal glue sizing applied to the canvas with an off-white oil priming. The evenly applied priming covers all the cloth, retaining its texture. The painting technique from squaring-up to finishing demonstrates that Gosse was familiar with helping Walter Sickert with the preliminary stages of his painting. His use of a substantial ‘camaieu’ or dead-colouring in a restricted colour range (see, for example, Tate N05288 and N04651) is reflected in Gosse’s almost monochrome underpainting. Sickert describes the manner of developing this underpainting before applying the ‘last skin of colour’ in several of his letters to pupils:

[I] put on the canvas still always in camaïeu the bit I have just drawn & observed while it is fresh ... These blond shadows ... being nearly all white dry & dry the more you repaint them the better. Then when the whole thing is absolutely complete in light & shade & drawing you just slip the last skin of colour on. In that way also you guide the effect more surely in pure line & light & shade.1

The image has been transferred to the canvas from a photographic source using a system of squaring up. Drawing pins remain around the edges at intervals of two inches. They were used to string black cotton thread to form a grid across the face of the canvas. Remnants of this cotton remain around the pins and there are faint ridges in the paint from its presence during painting. Many details, such as Sickert’s features and his clothing, are realised in the development of the blue-green underpainting before application of the final colours. The last colouring is applied in a wide variety of dabbed, drawn and scumbled brushstrokes of opaque colours to create a vibrant, broken surface with shallow impastos. The near grille (grisaille) underpainting and occasionally the white of the priming remain visible in many areas. The darks of the underpainting enhance the luminosity of the shadows while the light tints and white priming give liveliness to the lit surfaces. Scumbles of paint appear to have been applied over touch-dry paint as with the last, warm grey wispy touches to the wall. A thin surface film was rubbed onto the paint surface, giving a slightly uneven gloss to the surface, which is dulled around the matte black signature at the bottom right.

Roy Perry

November 2003

Notes

How to cite

Roy Perry, 'Technique and Condition', November 2003, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Walter Richard Sickert 1923–5 by Sylvia Gosse’, catalogue entry, April 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Walter Richard Sickert had an extraordinary facility for acquiring a loyal following of students and disciples, particularly younger women, who not only assimilated his teachings on art but provided a constant support network for the erratic, dominating, often demanding, but nevertheless charming artist. These admirers, whom the Parkin Gallery described in an exhibition of 1974 as the ‘Sickert women and Sickert girls’, included, in addition to Sylvia Gosse, who was the eldest, Thérèse Lessore (1884–1945, who married Sickert as his third wife in 1926), Wendela Boreel (1895–1985), Marjorie Lilly (1891–1980) and Christina Cutter (1893–1969). Boreel recalled how Sickert singled her out one day from the other students at the Slade in around 1911: ‘“Your drawing is far too good for here. I’ll install you in a studio in Mornington Crescent where you will paint each morning and then come to me in the afternoons”. So I became Sickert’s “petit nègre” [literally, little negro, meaning servant], to do all, and to be at his beck and call.’1 The most devoted of all of Sickert’s pupils was Gosse, whom Sickert’s first biographer Robert Emmons described in 1941 as the painter’s ‘firm friend and guardian angel’.2

Gosse first met Sickert in about 1908 at her family home in London. Her father was the eminent poet, author and critic Sir Edmund Gosse (1849–1928), and Sickert was one of a number of distinguished figures who frequented the house in Hanover Terrace, Regent’s Park. Sylvia Gosse hero-worshipped Sickert, who was twenty years her senior and already a well-established artist. In turn he was genuinely impressed by the quality of Gosse’s painting and took an interest in her development, encouraging her to study etching and eventually inviting her into partnership with him at his art school at Rowlandson House. For the rest of his life she supported him practically, emotionally, artistically and at times even financially, purchasing his work anonymously when he was especially short of funds. Whether he was working in Camden Town, Bath or Dieppe she chose to live close to him. In 1920 she helped to nurse Sickert’s frail wife, Christine, and after the latter’s death she bore the brunt of Sickert’s grief and depression. In later years she was one of the organising members of a fund to alleviate Sickert’s financial distress, and she helped Thérèse Lessore to look after the ageing artist until his death in 1942. She very often assisted in the studio, and prepared Sickert’s canvases, transferring the design from sketches or photographs and laying in the ‘camaieu’ under-painting in two or three shades of a single colour.

Photography

William Drummond Young (c.1850–c.1925) and Edward Drummond Young (c.1877–c.1946)

Portrait Photograph of Walter Richard Sickert 1923

Islington Local History Centre, London

© Estate of Edward Drummond Young

Photo © Islington Local History Centre

Fig.1

William Drummond Young (c.1850–c.1925) and Edward Drummond Young (c.1877–c.1946)

Portrait Photograph of Walter Richard Sickert 1923

Islington Local History Centre, London

© Estate of Edward Drummond Young

Photo © Islington Local History Centre

The photograph used by Gosse was taken in 1923 when Sickert was going through rather a difficult and unhappy period. He had returned from Dieppe in 1922 and was living as something of a recluse in London after the death of his second wife Christine in October 1920. In January 1923 he was persuaded to visit Edinburgh to deliver a series of lectures at several of the city’s art institutions and stayed there with some friends, William and Mary Price. According to Denys Sutton, on Sickert’s arrival, his hostess was horrified by the artist’s scruffy appearance, dressed like the Dickensian criminal ‘Bill Sykes’, with a peaked cap and a red handkerchief tied around his neck.9 He was immediately persuaded to buy some respectable new clothes and it seems to be these that he was wearing when he had his portrait photograph taken. He wrote to his sister-in-law Mrs Ronald Schweder that the Edinburgh visit was, ‘Such an amusing success ... I have been photographed “by request” for the window in Frederick Street in a silk hat like a writer to the Signet’.10

The professional photographer’s studio in Frederick Street to which Sickert was taken belonged to W. & E. Drummond Young, an established and successful father and son business specialising in portrait photographs. Both William Drummond Young (c.1850–c.1925) and his son, Edward Drummond Young (c.1877–c.1946), had studied painting as well as photography, and the work they produced seems to have been more creative and less conventional than many other studios of the period.11 Edward Drummond Young, in particular, was interested in the advancement of portrait photography as an art form. He delivered a number of lectures on the subject to the Edinburgh Photographic Society and taught drawing and photography at the College of Art. In 1929 he published a book, The Art of the Photographer, in which he established his theories on composition, lighting, background and the posing and treatment of sitters. The profile photograph of Sickert was obviously one which pleased Drummond Young and it is reproduced twice in The Art of the Photographer, as the frontispiece and again within the text.

In his book Drummond Young argues that photography and art have much in common and that one can be used in service of the other. He states that ‘the use of photography may be a great help in painting, but the artist should learn to handle the camera and keep his own view intact’. He believed that artists who dismissed the notion of photography as an art form were ‘overlooking the fact that a fine pictorial photograph is the result of trained control of the apparatus’.12 He also emphasises the importance for photographers of the understanding and appreciation of drawing, ‘for it makes one see form’.13 These are views which are very close to those upheld by Sickert and by association, presumably, by his protégée Sylvia Gosse.

The relationship between art and photography underwent a transformation in Sickert’s mind over the course of his career. During the 1890s he had been vociferous in his opposition to the practice of drawing from photographs, maintaining that ‘as a painter or a draughtsman works from photographs, so is he sapping his powers of observation and of expression. It is much as if a swimmer practised in a cork jacket, or a pianist by turning a barrel-organ.’14 He himself regarded drawing as the principal preparation for any painting and amassed a huge stock of his own sketches to which he could refer for inspiration. His canvases were carefully squared-up from drawn designs. This advice was drummed into all of his pupils and consequently was the technique adopted by Gosse throughout her life. However, in the later stages of his career, from around 1927, Sickert increasingly eschewed drawings and relied on photographs taken by himself or his wife, or on documentary images lifted from newspapers as the primary source material for his paintings. This practice earned him much adverse criticism and the assumption from many quarters that his artistic powers were waning. He defended his methods in print declaring that the camera ‘is the infallible, disinterested, and instantaneous witness’,15 and to ‘forbid the artist the use of available documents of which the photograph is the most valuable, is to deny to a historian the study of contemporary shorthand reports’.16 Like his studio photographer Drummond Young, however, he believed that when utilising photographic material, artists should not be ruled by the camera but should maintain their own creative vision and impulses, using it as a catalyst to recreate the image as something more powerful. In a lecture of 1934 he advised with regard to photographs:

You must be careful only to use them as a nucleus and not to study them without a proper visual angle. Let the line run away with you. You are more likely if you let the line run away from you to get it correct than if you are in a funk about it. Be careful that you know what you are doing and why you do it and that you do it on the proper scale of vision.17

Like Sickert, Gosse also adopted the use of photographic material in place of preparatory drawings for her paintings. Madrid Crowd 1931 (private collection),18 for example, is based upon a press clipping and is stylistically very close to Sickert’s later paintings with broad flat areas of colour applied in indistinct patches. Interestingly, although Gosse followed Sickert’s lead in so many respects, her use of a photograph as a basis for this 1923 portrait of Sickert seems to pre-date his own general adoption of the practice by a few years.

Description

Both the photograph and the painted portrait show the sixty-three-year-old Sickert in three-quarter length, right-hand profile, attired in a smart green overcoat and white scarf with gloved hands clasped behind his back, holding a walking cane. He stands in front of a light background against which is cast his looming shadow. Sickert often wore a beard but at the time of the photograph he was clean shaven and the hair visible beneath his shiny top hat is cut short. This choice of an uncompromising profile pose does little to disguise the signs of ageing apparent in Sickert’s heavy jowled face and slightly overweight figure. However, Edward Drummond Young believed that ‘while character is wanted in portraiture, caricature is to be avoided; and personal defects should not be exaggerated’.19 The photographic portrait of Sickert and the oil painting based upon it are serious and dignified likenesses, with the artist dressed in the attire of gentleman as befitted a person of success and achievement. Sickert’s meditative stance, concentrated expression and total disengagement from the viewer convey an impression of intellect and focused professionalism. The only part of the picture to throw suspicion upon this view is the slightly sinister shadow cast behind the figure of the artist.

Drummond Young recorded that when photographing Sickert the lighting was carefully projected from a single large source onto a background that had been turned to an oblique angle from the camera. This created a smaller, softer, diffused cast shadow behind the figure of the artist which is ‘not too definite or important & is free from any suggestion of caricaturing the subject’.20 In her painting, Gosse sharpened the outline of the shadow and painted it as a more solid mass in green-grey tones, very similar to those used in Sickert’s coat. The effect of this is rather more ominous than in the photograph. Gosse applied the paint in patches, building up the structure of Sickert’s figure through layers of colour. For example, in the treatment of the coat, an initial base colour of blue-green has been overlaid with a khaki green and traces of brown to denote the folds and highlights of the material.

Walter Richard Sickert offers an interesting insight into the friendship between Gosse and Sickert, over twenty years her senior. Gosse chose to paint a portrait where there is no direct interaction between the sitter and herself as artist/viewer. Considering Gosse’s legendary devotion to her teacher and that, when the portrait was painted in 1923, the two artists had been colleagues and friends for around fifteen years, the work reveals remarkably little indication of intimacy or shared experience between two equals. Instead, the painting portrays Sickert as a somewhat remote upright elderly figure, dignified by his professional success, whom the viewer respects and looks up to. It is interesting to compare Walter Richard Sickert to another portrait painted by Gosse, that of her father, Edmund Gosse (private collection), exhibited at the Summer Exhibition of the Royal Academy in 1912 and also repeated as an etching (British Museum).21 This image depicts Sir Edmund Gosse seated at the desk in his study at Hanover Terrace, surrounded by books and furniture and absorbed in his work. Like Sickert, he is portrayed in profile facing to the right and displays no awareness of the viewer. He is seen as a professional, successful and important man but he is unassailable within his working environment and there is little sense of emotion or filial affection which might be expected in a daughter’s portrait of her father. Throughout her life, Sylvia had in fact been frequently in the company of older, important and distinguished men, for example her aunt’s husband, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912), and her father’s many friends and contemporaries, who included such eminent figures as Henry James (1843–1916) and Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936). Gosse herself was always a shy, unassuming character about whom Thomas Hardy (1840–1928) reported, ‘I simply cannot get a word out of her’.22

In her portrait of Sickert, Gosse seems to be equating her view of him with that of a Victorian father figure, a person who is much loved and admired but with whom an unequal relationship exists, based on respect and deference, although perhaps with an awareness of vulnerability due to advancing old age. Her notion of the dominant, complex and impressive father figure may also have been formulated by her father’s extremely popular and highly acclaimed book, Father and Son. First published in 1907, the book is ‘the record of a struggle between two temperaments, two consciences and almost two epochs’,23 and is an account of Edmund Gosse’s troubled relationship with his caring but strict and religiously devout father, the eminent zoologist Philip Henry Gosse (1810–1888). Although Sylvia’s relations with her father were apparently always most affectionate and happy, his enormous professional success and charismatic personality were a forceful presence in her life, and his pride in her work was tempered by his inability to understand her lack of ambition.24 The complex emotions and pressures of the father-daughter relationship were to an extent repeated in Gosse and Sickert’s mentor-pupil friendship, a connection which is made evident in the painting, Walter Richard Sickert. Sadly, there is no record of what Sickert himself thought of Gosse’s portrait of him.

Ownership

The portrait was displayed by Gosse at a solo exhibition of her work at William Marchant’s Goupil Gallery in 1925, from where it was purchased and subsequently donated anonymously to the Tate Gallery a couple of years later. The art critic of the Evening Standard wrote: ‘I am glad to hear that Miss Sylvia Gosse’s portrait of Mr. Walter Sickert is to go to the Tate Gallery. It is an attractive solemn portrait, three-quarter length on a small canvas. When it was shown recently in Bond Street many of its admirers wondered if there might not be a fashion for portraits on the same scale.’25 Ann Thwaite, the biographer of Edmund Gosse, believes the mystery benefactor to have been the poet Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967).26 Sassoon, who lived close to the Tate Gallery and was a regular visitor, was on very friendly terms with the Gosse family. His mother, Teresa Sassoon (née Thornycroft), was an old school friend of Gosse’s mother Nellie. Sassoon himself had been friendly with Edmund Gosse since 1908 and had received much useful criticism from him, particularly during 1926–7 when Sassoon was writing Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man, first published in 1928. During frequent visits to Hanover Terrace he naturally also became friendly with the members of Gosse’s family, and following a visit in March 1925 recorded in his diary: ‘Sylvia was a great relief. She has such a sense of humour, and a keen eye for her father’s idiosyncrasies’.27 Sassoon was evidently able to penetrate her reserve, and through the Gosse family, he also became acquainted with Sickert, whose ‘terse and witty’ stories he relished and whom he observed with some interest and care in 1924:

S. [Sickert], shaven, bare-headed and pale, looks like a distinguished French actor ... Rather a high-pitched voice, fine diction, eyes tired and rather screwed-up. Trick of rounding off a story or pointed remark by throwing up his head and laughing with his mouth a wry hole in his face, rather as if he were going to whistle. Eyes rounded also, heavy eyebrows, but fine arch of brow. Upper part of face beautiful. Mouth and chin not so good – a little meagre and peevish.28

It is not known what Sassoon thought of Gosse’s painting but perhaps his decision to purchase her portrait of Sickert reminded him of his encounters with the famous painter. His generous gesture of donating the work to the Tate Gallery in November 1927 was possibly a compliment directed as much to his old friend Sir Edmund Gosse who died the following year, as to his fellow writer’s youngest daughter.

Nicola Moorby

April 2003

Notes

National Portrait Gallery NPG 3775. Reproduced at National Portrait Gallery, London, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/largerimage.php?firstRun=true&sText=sylvia+gosse+lansbury&search=sp&rNo=0 , accessed 18 February 2011.

Information on William and Edward Drummond Young supplied by Peter Stubbs, April 2003, http://www.edinphoto.org.uk/ , accessed April 2003.

Walter Sickert, ‘Is the Camera The Friend or Foe of Art?’, Studio Magazine, July 1893, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford and New York 2000, p.97.

Walter Sickert, ‘Black and White Illustration’, Lecture, 30 November 1934, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.665.

Reproduced in Sylvia Gosse 1881–1968: Paintings and Prints, exhibition catalogue, Michael Parkin Gallery, London 1989 (20).

Related biographies

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Walter Richard Sickert 1923–5 by Sylvia Gosse’, catalogue entry, April 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www