Charles Ginner Piccadilly Circus 1912

Charles Ginner,

Piccadilly Circus

1912

The central focus of this painting of Piccadilly Circus is a ‘coster girl’, or flower-seller, sitting in the centre of this famous London junction. The flower-seller’s stillness contrasts with the hustle and bustle around her – the hurrying figure of the smartly dressed woman, the taxi barrelling into the foreground and the two buses with their busy route boards and advertisements.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Piccadilly Circus

1912

Oil paint on canvas

813 x 660 mm

Inscribed ‘C. GINNER’ in green oil paint bottom right, and various notices on the vehicles and buildings.

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1980

T03096

1912

Oil paint on canvas

813 x 660 mm

Inscribed ‘C. GINNER’ in green oil paint bottom right, and various notices on the vehicles and buildings.

Purchased (Grant-in-Aid) 1980

T03096

Ownership history

Sold by the artist with a group of his paintings to T.W. Spurr and Son, Southport, 1934; ... ; H. Holdsworth, Halifax, who sold it at Christie’s, London, 15 July 1938 (100), for 2 guineas; bought by Webberley Gallery, Toronto (the Webberley Gallery moved to Chicago in 1942); ... ; anonymous sale at Christie’s, London, 1 March 1974 (114, reproduced), 8,500 guineas bought by Edward Garrett; bought by Anthony d’Offay Ltd, London, 1980, by whom sold to Tate Gallery.

Exhibition history

1912

The Third Exhibition of the Camden Town Group, Carfax Gallery, London, December 1912 (24).

1913

Fitzroy Street Group display, 19 Fitzroy Street, London, early 1913.

1913

Société des artistes indépendants, Quai d’Orsay, Paris, March–May 1913 (1281, as ‘Piccadilly Circus (Londres)’).

1913–14

Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others, Public Art Galleries, Brighton, December 1913–January 1914 (29, £35).

1914

An Exhibition of Paintings by Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner, Goupil Gallery, London, April–May 1914 (19).

1938–45

Galleries of three department stores, Eatons, Toronto, Hudsons, Detroit, and Marshall Fields, Chicago, 1938–45 (no catalogues).

1979

Paintings of London by Members of the Camden Town Group, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London, October–November 1979 (13).

1987

British Art in the Twentieth Century: The Modern Movement, Royal Academy, London, January–April 1987 (18, reproduced).

1994

La Ville: Visions urbaines, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, February–May 1994, Centre de Cultura Contemporania, Barcelona, June–October 1994 (no number, reproduced p.224).

1998

Masterpieces of British Art from the Tate Gallery, (British Council tour), Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, January–March 1998, Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Kobe, April–June 1998 (84, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (25, reproduced).

References

1912

G.R.H., ‘Gallery and Studio’, Pall Mall Gazette, 12 December 1912, p.7.

1912

W.R., ‘Round the Galleries. The Camden Town Group’, Sunday Times, 29 December 1912, p.6.

1976

Wendy Baron, Camden Town Recalled, exhibition catalogue, Fine Art Society, London 1976, pp.27–8.

1979

Charles Harrison, ‘The Camden Town Group’, Art Monthly, no.31, November 1979, p.8.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, p.311, reproduced p.313.

1982

Richard Cork, ‘The Cave of the Golden Calf’, Artforum, vol.21, no.4, December 1982, p.68, n.20.

1984

The Tate Gallery, Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1980–82, London 1984, pp.100–1, reproduced p.100.

1985

Richard Cork, Art Beyond the Gallery in Early 20th Century England, London 1985, p.303, n.80.

1987

Susan Compton (ed.), British Art in the 20th Century: The Modern Movement, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1987, p.66.

1987

Celina Fox, Londoners, London 1987, pp.166–7, reproduced p.167.

1988

Francis Farmar, The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988, p.150.

1990

Simon Wilson, Tate Gallery: An Illustrated Companion, London 1990, p.128, reproduced p.127.

1994

Eric Shanes, Impressionist London, New York and London 1994, pp.153–7, reproduced fig.127.

1997

James Malpas, Realism, London 1997, p.19, reproduced fig.8.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, pp.51, 120, 151, 175, reproduced pl.54.

Technique and condition

Piccadilly Circus is painted in artists’ oil paints on primed stretched canvas. The original stretcher has been replaced and the canvas has been lined. The original cloth appears to be of a similar type to that used for Victoria Embankment Gardens (Tate T03841). It is a plain, coarsely woven jute cloth with a heavy tooth, which has probably been sized and also appears to have the same off-white double priming. This type of canvas is prone to embrittlement with age and its weakest points, the tacking edges, would have been put under extra strain by the weight of the substantial paint film, causing them to split and eventually break away.

No initial drawing remains visible. Outlines that delineate form are applied at all stages of painting, being revised or reinforced as required. The paint thickness is in excess of 2 mm deep in most areas. Brushes up to 6 mm wide were used to apply the paint in short linear strokes often modelling the contours of the forms. In order to attain several millimetres thickness and tightly control the application, the paint would have had to be a particular viscosity. Ginner may not have used paint direct from the tube but may have mixed it on his palette to achieve the desired consistency. It has been suggested that he used ‘stand oil’, which would be consistent with the quality of the paint,1 and added this to colourman’s tube paints (see also Tate N05695). Brushwork is laid on both wet-on-dry and wet-in-wet but the relatively stiff paints seldom merge, each retaining its hue, tone and texture. Broken strokes leave underlying layers in contrasting colours visible, creating a sparkling sense of light. And small gaps and crevices are deliberately left between shapes, where brushstrokes are laid next to but not over the outline.

Open ductile cracks developed during shrinkage of the paint, and as it hardened with age, brittle cracks continued to develop through the paint and priming. The cracks are typically at right angles to the brush marking, forming interconnecting patterns in the worst affected areas such as the greens. The islands of paint formed by the interconnecting cracks would have cupped a little. Cracked and cupping paint was secured and flattened during the lining process. This type of cracking, varying in its extent, was found on all of Ginner’s paintings and is primarily due to the thickness and related drying properties of the paint film.

Roy Perry

June 2004

Notes

How to cite

Roy Perry, 'Technique and Condition', June 2004, in David Fraser Jenkins, ‘Piccadilly Circus 1912 by Charles Ginner’, catalogue entry, May 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Subject

Ginner’s view of Piccadilly Circus in central London shows at the right the island pavement around the base of Alfred Gilbert’s statue of Eros, where a coster woman is seated on a stool selling flowers from two baskets. A smartly dressed woman in a large hat walks past, while a man to the left is partly hidden by a taxi. The taxi, two buses and a car driving around the island are shown in detail, complete with their advertisements and route signs, but their forms are difficult to make out exactly as they overlap. The viewpoint looks south towards the Criterion Grill Room and the building to its east, although the architecture in the background, which is not much of a feature of the painting, is simplified and not quite accurate in detail.1

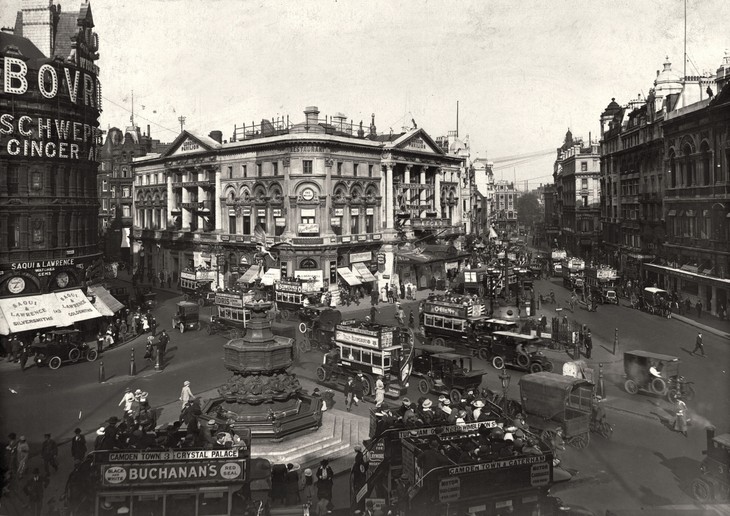

To see this view, Ginner must have placed himself on the pavement near the Regent Street quadrant, or, more likely, within the traffic between a row of bollards that were then dividing the road into separate lanes. A photograph of Piccadilly Circus taken from an upper window in 1910 shows a flower-seller sitting in the same spot (fig.1). In this photograph several smart-looking people are walking by briskly, as in the painting, using the island as a shortcut between Regent Street and Leicester Square. The painting is larger than usual for Ginner, and is focused on the figure of the flower-seller, whose mauve scarf stands out, and who is placed beside the strongest colours in the picture, her red flowers (which are possibly anemones and chrysanthemums).

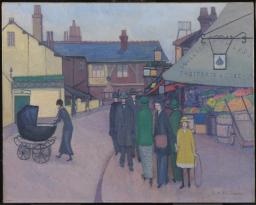

The notices on the buses are prominent and seem to be recorded accurately. The bus in the centre of the painting has the route boards, ‘CLAPHAM JUNCTION (19) HIGHBURY B[...]’ and ‘BATTERSEA BR[IDGE] KINGS Rd SLOANE (19) PICCADILLY TOTTENH[AM] | BLOOMSBURY ANGEL ISLING[TON] | HYDE PAR[K S]HAFTESB[URY]’. It carries an advertisement for the theatre ‘THE | NEW | ALHAMBR[A] | REVUE | ATTRACTION | ATMOSPHERE’. These details link some of Ginner’s favourite places. Performances at the Alhambra Theatre were a particular subject of Spencer Gore, and Ginner himself included its exterior in his Leicester Square 1912 (fig.2).

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Leicester Square 1912

Oil paint on canvas

642 x 559 mm

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Fig.2

Charles Ginner

Leicester Square 1912

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

The Sunlit Square, Victoria Station 1913

Oil paint on canvas

43 x 51 cm

Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

Fig.3

Charles Ginner

The Sunlit Square, Victoria Station 1913

Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © Atkinson Art Galley, Southport, Sefton M.B.C.

The vehicle with the registration number ‘LN 5834’ on the left is a taxi. The ‘GENERAL’ on the sides of the two buses shows that both were owned or operated by the London General Omnibus Company. The small plate on the nearer bus inscribed ‘B5’ indicates that it was based at Battersea Garage. ‘B type’ buses were introduced in 1910.2 ‘B1218’, the nearer of the two buses seen in the picture, appears to have an illuminated box at the front for the route number. If so, and it is not at all clear, Ginner was up to date, as this light was first installed in the summer of 1912.3 He liked crowded scenes and overlapping details, and in his picture of the forecourt of Victoria Station, The Sunlit Square, Victoria Station 1913 (fig.3), he again included details of buses, showing them in a sharply receding perspective.

John Thomson 1837–1921

Covent Garden Flower Women, from 'Street Life in London' 1877–8

Photograph, Woodburytype

109 x 84 mm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.4

John Thomson

Covent Garden Flower Women, from 'Street Life in London' 1877–8

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

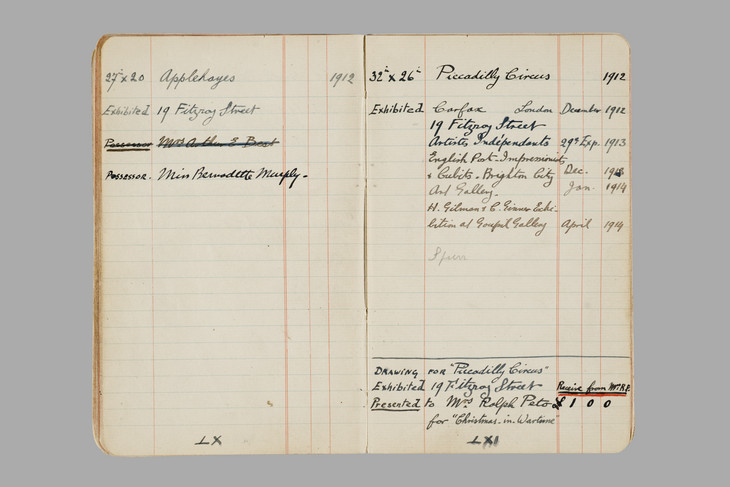

Fig.5

Charles Ginner

List of Paintings, Drawings, Etc. of Charles Ginner. Book I 1910–18

Tate Archive TGA 9319/1

Other depictions

Several artists had painted Piccadilly Circus early in the century, including an impressionist view by the German painter Joseph Oppenheimer in 1900.10 Pictures of the new street lights already existed. In 1910 Muirhead Bone exhibited his drawing of Piccadilly Circus by night that he had made in 1907,11 with this note in the catalogue:

The enormous increase recently in the amount and variety of artificial lighting has greatly added to the pictorial effect of London by night. The stucco and Portland stone, of which much of central London is built are specially good reflectors, and at present the Strand and Piccadilly Circus afford us, nightly, strange dramas of competing lights, seen against the soft dun opaqueness of the city night sky, which the artist so marvellously relieves of its black monotony.12

Bone’s drawing was a detailed topographical study of buildings and lighting, and shows that in 1907, just a few years before the painting by Ginner, there were no motor cars or buses (or if there were, Bone ignored them).

Arthur Hacker 1858–1919

A Wet Night at Piccadilly Circus 1910

Oil paint on canvas

710 x 915 mm

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London

Fig.6

Arthur Hacker

A Wet Night at Piccadilly Circus 1910

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London

William Logsdail 1859–1944

St Martin-in-the-Fields 1888

Oil on canvas

support: 1435 x 1181 mm; frame: 1588 x 1388 x 106 mm, 47 kg

Tate N01621

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1888

© The estate of William Logsdail. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.7

William Logsdail

St Martin-in-the-Fields 1888

Tate N01621

© The estate of William Logsdail. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

At the Royal Academy exhibitions in 1910–12 paintings of central London were rare, with the striking exception of an artist a generation older, Arthur Hacker (fig.6). Hacker was elected a Royal Academician in 1910 and, suddenly, having been a portrait and figure painter all his life, sent four paintings of Piccadilly Circus and the area nearby, including the interior of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, to the Academy for exhibition in 1911. The reason for this change of subject is not known, but the pictures are dark, Whistlerian scenes of the evening by artificial light. They may have depended on the striking effect of improved street lighting. Ginner’s kind of insistent close focus on people and their surroundings had hardly been attempted since William Logsdail’s elaborate views of Victorian London with crowds of people, including portraits of his friends, as in for example St Martin-in-the-Fields 1888 (Tate N01621, fig.7).

London as a subject for modern art had been revealed with the 1904 exhibition in Paris of Claude Monet’s recent paintings of the city.13 When the German art critic Julius Meier-Graefe’s Modern Art was published in English translation in 1908, readers of the authoritative volumes found, following his scorn for British painting, an exhortation to the modern artist to paint London not in the misty, Whistler fashion, but ‘using luminous colour to render the London atmosphere, in which the essential element is not the dust, but the colour’.14 This was in a section on Monet, which he explained was written before he had seen Monet’s series of paintings of the Thames. Admiration for these works led the same dealer who had commissioned them, Ambroise Vollard, to ask André Derain for a group of London paintings. Derain painted his during and after two visits in the winters of 1906 and 1907. Many of them are of the Thames and all are in strident fauvist colours.15 Derain’s paintings of bridges and barges were not shown prominently in Paris, but two of them, of the London Embankment and of the river with St Paul’s Cathedral,16 were displayed in the Modern French Art exhibition at the Brighton Public Art Gallery in the summer of 1910. The art critic Frank Rutter reviewed them favourably and at length in August 1910.17 There is no record of any interest Ginner had in Derain, but he knew Rutter well, and this exhibition at least gave an idea of what a modern French artist working in London could do. Along with Meier-Graefe’s suggestion, Derain’s paintings set precedents for Ginner’s use of strong colour,18 and for his central London paintings as a group (and, in the case of Victoria Embankment Gardens [Tate T03841], for one of the subjects).

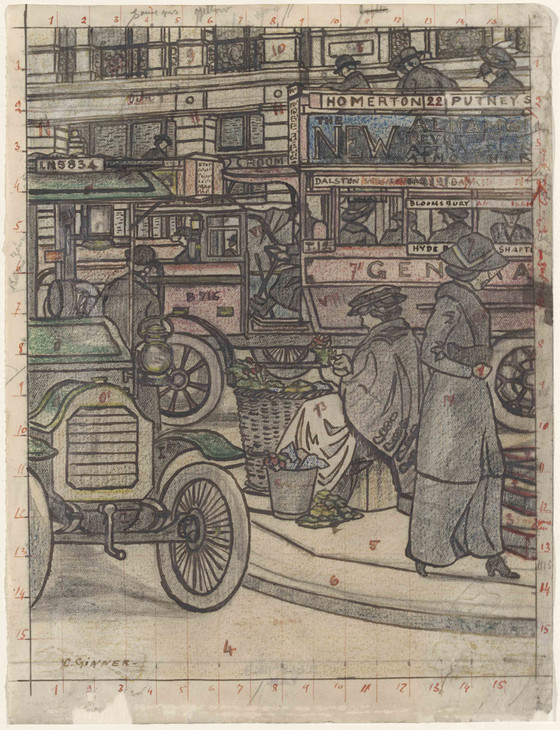

Style and reception

There is no record of Ginner making paintings from photographs, and the art historian Malcolm Easton asserted that ‘Ginner himself never used a camera’.19 It is therefore likely that Ginner made sketches on the spot for the picture, but he must have drawn the vehicles when they were stationary. The same notebook page on which he lists the oil also cites a drawing for the painting as having been displayed at 19 Fitzroy Street and then presented to Mrs Ralph Peto for ‘Christmas-in-Wartime’.20 This may have been a charity sale, though Ginner also notes that he received £1 for it from Mrs Peto. There is a completed study for the painting, drawn on thin paper, which is almost exactly the same (fig.8). This drawing is too untidy to have been intended for exhibition, although it is signed, and is presumably the design which was transferred to the painting as there are numbered squares in the margins (in fact they are not squares but rectangles, as the drawing is more tall than wide, yet the numbers are from 1 to 15 on the sides and the top and bottom). The one difference is that in the drawing the bus at the right is a number 22, the route between Homerton and Putney. This carries different route notices from the bus in the painting, but the advertisement for the Alhambra is the same, though the canopy above the driver is different and it is not certain that it includes the new kind of box for the route number. In addition, the design is altered slightly, as Ginner made the bus in the painting almost parallel to the edges, but in the drawing it is at more of an angle. In addition to colour notes and numbers marking the squares, Ginner wrote on the drawing a sequence of numbers from 0 to 11, with also some Roman numerals and smaller numbers. The purpose of these is not known, but might be the order in which he planned to put on the colours.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Study for 'Piccadilly Circus' 1912

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.8

Charles Ginner

Study for 'Piccadilly Circus' 1912

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Of Mr Ginner’s exhibits, Piccadilly Circus (24) is by far the most interesting. It is interesting, however, from a technical standpoint and will appeal to his fellow painters rather than to those who are concerned with pictures apart altogether from the question of paint and its manipulation.21

The art critic of the Pall Mall Gazette thought its qualities were intentionally negative, being to convey the effect of modern traffic: ‘Piccadilly Circus both in its crude tones and jumbled composition, happily suggests the noise and confusion of that busy thoroughfare.’22

No critic at the time, so far as is known, linked the painting with the work of the Italian futurists, but this plunging into traffic and movement remained unusual for Ginner, who might have been encouraged to take it on as a response to similar futurist subjects.23 The first international futurist exhibition had travelled from the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris in February 1912 to the Sackville Gallery in London in March. In his notebooks Ginner listed a drawing for a large poster titled Piccadilly Circus also of 1912 as a ‘Cubist design’.24 This was one of two posters measuring 7 by 4½ feet (c.213 x 137 cm) for the Cave of the Golden Calf nightclub, both painted in ‘distemper’. The club opened in June 1912, and these were presumably large decorative pictures with lettering, and may, as the art historian Richard Cork suggests, ‘have been displayed near the entrance as an overture for the far larger decorations beyond’.25 An illustration of the poster, seen also by Malcolm Easton, was noted by the art historian Hazel Williamson.26 She describes Piccadilly Circus as ‘clearly indebted to the Futurists’ preoccupation with modernity, machinery and noise’.27 A reproduction of a poster depicting Piccadilly Circus in the French newspaper L’Actualité on 10 November 1912 is most probably Ginner’s work (fig.9).28

Ownership

The notebooks show that Ginner exhibited Piccadilly Circus five times up to 1914 without finding a buyer, and eventually sold it in 1934 to T.W. Spurr.29 Spurr, an art dealer in Stockport, bought a quantity of Ginner’s work, evidently when these early paintings were unpopular and cheap, but when the artist was glad to have the money. After being sold for two guineas at Christie’s in 1938 at the lowest point of Ginner’s market, the picture was bought, unusually, by a gallery in Toronto (which later moved to Chicago) and was shown in picture galleries in department stores in Canada and America. It was effectively rediscovered at a sale at Christie’s in 1974, when the Tate Gallery tried to buy it. The reversal in the fortunes of the painting was completed when it was included in 1998 in a tour to Japan of ‘masterpieces’ from the Tate collection.

David Fraser Jenkins

May 2005

Notes

At this time the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain was in the centre of the junction some distance from the Criterion; it was not until the 1980s that the statue was moved to its current site at the south-western corner of Piccadilly Circus, close to the Criterion.

Information from G.W.B. Lacey, Science Museum, letter to Richard Morphet, 15 December 1982, Tate Catalogue file.

Information from Oliver Green, Curator, London Transport Museum, letter to Richard Morphet, 11 January 1983, Tate Catalogue file.

See, for example, Thomas Burke, Out and About: A Note-Book of London in War-Time, London 1919, pp.81–3.

P.F. William Ryan, ‘London’s Flower Girls’, in George R. Sims (ed.), Living London, vol.2, London 1906, p.50.

Reproduced in British Drawings and Watercolours 1890–1940, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1982 (29).

Reproduced in Impressionism in Britain, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1995 (156).

Sylvie Patin, ‘The Return of Whistler and Monet to the Thames’, in Turner Whistler Monet, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2004, p.189.

Julius Meier-Graefe, Modern Art: Being a Contribution to a New System of Aesthetics, vol.2, translated by Florence Simmonds and George W. Chrystal, London 1908, p.303.

Remi Labrusse and Jacqueline Munck, ‘André Derain in London (1906–07): Letters and a Sketchbook’, Burlington Magazine, vol.146, no.1213, April 2004, pp.243–50.

There are several paintings by Derain of the Thames embankment, see Michel Kellermann, André Derain, catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, vol.1, Paris 1992, nos.93, 94 and 95. The view of St Paul’s must have been Londres: La cathédrale Saint Paul vue de la Tamise, reproduced ibid., no.103, now at Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

See Anna Gruetzner Robins, Modern Art in Britain 1910–1914, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1997, p.197, n.2.

See Richard Cork, Art Beyond the Gallery in Early 20th Century England, London 1985, p.303, and Hazel R. Williamson, The Theory and Practice of Neo-Realism in the Work of Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner, unpublished Ph.D thesis, University of Leicester 1992, pp.133–43.

Easton 1970, p.206; listed in Ginner’s first notebook as being reproduced in Lady’s Realm, April 1912; see Tate Archive TGA 9319/1, p.CXXXV.

Related biographies

Related essays

- City Visions: The Urban Scene in Camden Town Group and Ashcan School Painting David Peters Corbett

- Empire and the City: Early Films of London Maurizio Cinquegrani

- London’s Fashion Culture and the Camden Town Group Painters Christopher Breward

- The Evolution of Painting Technique among Camden Town Group Artists Stephen Hackney

- Sex and the City: The Metropolitan New Woman Meaghan Clarke

- The Urban Observer Deborah Longworth

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- G.R.H., ‘Gallery and Studio. The Camden Town Group’ Pall Mall Gazette, 12 December 1912, p.7.

- W.R., ‘Round the Galleries’ Sunday Times, 29 December 1912, p.6.

Related audio

-

Marie Lloyd 1870–1922 performs 'Piccadilly Trot' recorded November 1912© Windyridge Music Hall CDs

Related film

-

Busy traffic in central London, including motor cars, buses and pedestrians passing by the Shaftesbury Memorial in its original position in the middle of Piccadilly Circus 1911© British Pathé

How to cite

David Fraser Jenkins, ‘Piccadilly Circus 1912 by Charles Ginner’, catalogue entry, May 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www