Walter Richard Sickert L'Américaine 1908

Walter Richard Sickert,

L'Américaine

1908

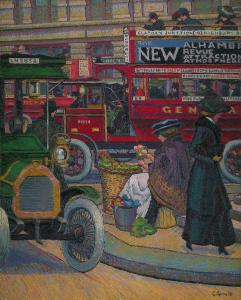

The focal point of this picture is the flat-crowned straw boater hat commonly worn by costermongers, or female street-sellers, during the Edwardian period. This characteristic accessory was known as an ‘American Sailor’ hat, from which the painting’s title is drawn. The figure’s downward gaze and delicately raised hand strike a flirtatious pose, reinforcing the positive stereotype of the working class woman’s attractive vitality. Her cobalt blouse and the strong reds, yellows and oranges of her complexion show the influence of the Camden Town Group’s bright palette on Sickert’s painting at the time.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

L’Américaine

1908

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 406 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert – 1908.’ in red paint bottom right; traces of an obliterated signature in red paint top right.

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05090

1908

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 406 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert – 1908.’ in red paint bottom right; traces of an obliterated signature in red paint top right.

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05090

Ownership history

... ; ?sold Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, 21 June 1909 (4, as ‘The American Sailor Hat’); purchased by Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck (1863–1931), London, from the Goupil Gallery, London, 1925; inherited by his wife, Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, by whom bequeathed to Tate Gallery 1940.

Exhibition history

1909

Vente de 84 Oeuvres de Walter Sickert, Bernheim-Jeune, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, June 1909 (4, as ‘The American Sailor Hat’).

1925

Spring Exhibition, Goupil Gallery, London, March 1925 (71, as ‘L’Américaine’).

1933

Retrospective Exhibition of Pictures by W.R. Sickert, A.R.A., Agnew & Sons Ltd., London, November–December 1933 (24).

1936

A Loan Exhibition of Paintings & Drawings, St John Ambulance Hall, Kendal, April–May 1936 (10).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (7, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (37, reproduced).

References

1955

Anthony Bertram, Sickert, London and New York 1955, reproduced pl.21.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, pp.29, 74, 101, reproduced pl.54.

1960

Wendy Dimson, ‘Four Sickert Exhibitions’, Burlington Magazine, vol.102, no.691, October 1960, p.442.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, p.630.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, pp.107, 348, no.266, reproduced pl.185.

1976

Wendy Baron, Camden Town Recalled, exhibition catalogue, Fine Art Society, London 1976, p.47.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.164, 390.

1992

Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, p.204, reproduced fig.146.

1996

Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: Drawings, Aldershot and Vermont 1996, p.26.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.205.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.349, reproduced.

Technique and condition

For L’Américaine Walter Sickert bought a pre-primed canvas from Percy Young, which was similar to that purchased from the same artists’ colourmen for La Hollandaise (Tate T03548). He clearly chose the canvas for its strong texture: the cloth is made of a mixture of thick hemp fibres and thinner flax [linen] fibres producing a coarse heavy canvas with a pronounced plain open weave. The canvas is attached to a four-member stretcher with widely spaced, zinc-coated tacks. It has been sized with glue and fully primed with a thin layer of lead white and chalk over a thicker more transparent layer of chalk, zinc white and lead white.1

The artist applied a thin wash of grey-brown paint over the commercial priming as an ‘imprimatura’ or toning layer. He then drew his composition in paint onto this layer apparently without any other preliminary underdrawing. He worked over the entire painting on more than one occasion, modifying and reworking areas. It is likely that he allowed time for the paint to dry between applications but it is not clear how many campaigns took place. The paint was brushed in a reasonably viscous state so that it bounced across the surface and was partly rejected by the dry underlayer, reinforcing the texture of the canvas. His touch was probably quite light on the face and in detailed areas he used less paint, employing fine diagonal hatching and touches in the face. Dabs of impasto appear throughout and in some darker and less important areas there is a heavier accumulation of paint where he has loaded his brush and pushed the paint across the surface. There is some wet-in-wet mixing on the painting but this is confined to local areas and is probably largely incidental. The entire surface has been covered with paint leaving no white priming visible and little imprimatura. Some small patches of white paint have been applied as highlights, evidence that he has used a mid/dark ground technique.

The palette is quite strong for Sickert: as well as the usual blacks, browns, greys and dull greens he has used strong reds, oranges, yellows and blues; for example, a small patch of pure blue, possibly cobalt, can be seen in the earlier form of the blue blouse. This departure from his usual palette may reflect Spencer Gore’s influence since, in comparison with the younger Camden Town Group artists, Sickert remained reluctant to employ pure colour unmixed with black or contrasting colours, and there is much reworking of the colours in this painting.

The work is signed at the bottom right-hand corner in red paint, but there are traces of what appear to be an overpainted signature in the top right-hand corner in the same paint.

Stephen Hackney

July 2004

Notes

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', July 2004, in Nicola Moorby, ‘L’Américaine 1908 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, March 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

The title of Sickert’s painting, L’Américaine, refers not to the nationality of the sitter but to her distinctive ‘American Sailor’ hat, a flat-crowned straw boater which was commonly worn during the Edwardian period and was a characteristic feature of the costume of the female London street-sellers known as costermongers. It is one of a number of images by the artist dating from 1908–11 which depict one or more models wearing this particular type of hat. In a letter to Mrs Hugh Hammersley, speculatively dated December 1907, Sickert wrote that he was currently working from ‘two coster girls in the hats called “American sailors” between whom my progress is as transparent & embarrassed as Garrick’s between the two muses’.1 The painting was first exhibited in Paris in 1909 as The American Sailor Hat, but by the time it was shown at the Goupil Gallery in London in 1925 it had acquired the more misleading label, L’Américaine. This perhaps reflects a tendency by Sickert to bestow French titles suggestive of nationality upon pictures of anonymous women, for example, La Jolie Veneitienne 1903–4 (private collection),2 La Belle Sicilienne c.1905 (David Fullen),3 La Belle Rousse 1905 (private collection),4 Les Petites Belges 1906 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston),5 The Belgian Cocotte 1906 (Arts Council Collection, London),6 and La Hollandaise c.1906 (Tate T03548).

A sketch of L’Américaine appears in an undated letter to his friends Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson in which Sickert reported that he was:

deep in two divine coster girls – one with sunlight on her indoors. You know the trompe l’oeil hat all the coster girls wear here with a crown fitting to the head inside & expanded outside to immense proportions. It is called an “American Sailor” (hat).7

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The New Home 1908

Oil paint on canvas

495 x 390 mm

Private collection, Ivor Braka Ltd

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ivor Braka Ltd, London

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

The New Home 1908

Private collection, Ivor Braka Ltd

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ivor Braka Ltd, London

Coster-girls were a source of visual fascination for other artists and writers besides Sickert.14 The tradition of depicting street traders had been established as early as the sixteenth century through a genre of art known as ‘Cries’, romanticised images of individual urban characters identified with a particular trade or product.15 Produced by artists for patrons higher up the social scale, popular print series such as Marcellus Laroon’s The Cryes of the City of London Drawne after the Life 1688, Paul Sandby’s Twelve Cries of London 1760, and Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London 1790s, catalogued an array of national working class types, each peddling their various wares. These images portrayed an idealised, sanitised view of the lower classes which ignored the privations and drudgery of the social reality, and female street hawkers, in particular, such as the milkmaid or the flower seller, were often sentimentalised and aestheticised. The pink-cheeked protagonist of William Hogarth’s The Shrimp Girl c.1745 (National Gallery, London),16 for example, epitomises an appealingly robust type of femininity.17 The art historian Ysanne Holt has discussed how this tradition was perpetuated in the late nineteenth century by images of working class women which displaced contemporary middle class anxieties about urban degeneracy and decline.18 Paintings such as William Rothenstein’s The Coster Girls 1894 (Sheffield City Art Galleries) and William Nicholson’s series of wood-engravings, London Types 1898, isolated certain physical and emotional qualities popularly associated with the cockney woman, such as comely well-being, saucy insolence and heroic resilience.19 This type found ultimate expression in the Covent Garden flower girl, Eliza Doolittle, the pert heroine of George Bernard Shaw’s play, Pygmalion, published in 1913.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Two Women c.1911

Oil paint on canvas

508 x 406 mm

Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Two Women c.1911

Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston

Nicola Moorby

March 2009

Notes

Quoted in Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, p.368. The letter is dated by an unknown hand December 1907.

Ibid., no.350.6; reproduced in British and Irish Traditionalist and Modernist Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, Christie’s, London, 3 March 1989 (lot 309).

Drawings by Walter Sickert, exhibition catalogue, Carfax Gallery, London 1911 (32), Tate Archive. Reproduced in Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: Drawings, Aldershot and Vermont 1996, p.89.

Reproduced in Ruth Bromberg, Walter Sickert Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London 2000, no.126.

See Mark Hallett and Christine Riding, Hogarth, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2006, pp.121, 124–7.

Reproduced at the National Gallery, London, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/william-hogarth-the-shrimp-girl , accessed March 2011.

See Nicola Moorby, ‘Portrait / Figure / Type’, in Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008, p.97.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Walter Richard Sickert, ‘The Study of Drawing’ The New Age, 16 June 1910, pp.156–7.

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘L’Américaine 1908 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, March 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www