The Urban Observer

Deborah Longworth

The urban scenes of the Camden Town Group form part of a long tradition of observing London. Deborah Longworth reconsiders the figure of the artist-flâneur in the light of this tradition. She also examines the role of the woman observer, exemplified in Dorothy Richardson’s thirteen-volume novel Pilgrimage (1915–67).

In January 1801 the essayist Charles Lamb wrote to his friend William Wordsworth to decline an invitation to Cumberland, admitting that he could not bring himself to give up the daily rush of the city for the tranquillity of the Lakes. ‘Separate from the pleasure of your company,’ he wrote politely but firmly to his friend, ‘I don’t much care if I never see a mountain in my life’:

I have passed all my days in London, until I have formed as many and intense local attachments as any of you mountaineers can have done with dead nature. The lighted shops of the Strand and Fleet Street; the innumerable trades, tradesmen, and customers; coaches, wagons, playhouses; all the bustle and wickedness round about Covent Garden; the very women of the town; the watchmen, drunken scenes, rattles; life awake, if you awake, at all hours of the night; the impossibility of being dull in Fleet Street; the crowds, the very dirt and mud, the sun shining upon houses and pavements; the print-shops, the old-book stalls, parsons cheapening books; coffee-houses, steams of soups from kitchens; the pantomimes, London itself a pantomime and a masquerade, – all these things work themselves into my mind, and feed me without a power of satiating me. The wonder of these sights impels me into night-walks about her crowded streets, and I often shed tears in the motley Strand from fulness of joy at so much life. All these emotions must be strange to you; so are your rural emotions to me.1

‘In Lamb London found its one poet’, the impressionist poet Arthur Symons, quoting this letter, declared in 1906.2 As Symons recognised, Lamb’s account of his aesthetic response to the city is a paradigm of the sentiments and proclivities of the flâneur, the strolling, leisured observer of urban life who was fast becoming a characteristic figure within early nineteenth-century London and Paris. If, as Lamb acknowledges, such enthusiasm for the city was anathema to Wordsworth, for whom creative energy was to be found amidst the natural grandeur of mountains and lakes, so, in turn, the flâneur finds no inspiration in what Lamb describes as ‘dead nature’, requiring the crush and variety of the city’s seething streets if he is not, as he wrote the following year, to ‘mope and pine away’.3

With a penchant for abandoning himself to the bustle and variety of the urban crowd, and never happier than with the façades of buildings as his walls and the sky as his ceiling, the flâneur found his ideal habitat in the busy thoroughfares, shopping arcades and coffee shops of the burgeoning metropolis. Wordsworth could find beauty in London, and only a year later, when viewing the city in the early morning, empty and at rest, was inspired to write the sonnet ‘Lines Composed Upon Westminster Bridge’ (1802), in which he declares that ‘Earth has not anything to show more fair’ as London’s ‘[s]hips, towers, domes, theatres, and temples ... All bright and glittering in the smokeless air’.4

Yet the poet’s eye could only rarely assume the kind of ordered, panoramic perspective offered by Westminster Bridge in the early morning, and Wordsworth’s more common response to the city was that of his recollection of his brief residence in the capital in the early 1790s in Book Seven of The Prelude (1805), in which he recoils from the city as a ‘monstrous ant-hill on the plain / Of a too busy world!’.5 In contrast to Lamb, who rejoices in the ‘motley’ of the Strand and Fleet Street as the very life-force of London, Wordsworth perceives the same ‘quick dance / Of colours, lights, and forms; the Babel din; / The endless stream of men, and moving things’ in the manner of a nightmare.6 His mind overwhelmed by the rush and variety of sensory stimuli bombarding his perception, for Wordsworth the city is a grotesque spectacle, while its multitude, ‘Living amid the same perpetual whirl / Of trivial objects, melted and reduced / To one identity’, seems blank and alienating.7 ‘The face of everyone that passes by me is a mystery!’, the poet exclaims to himself.8 While Wordsworth was repelled by the anonymity of city life, however, Lamb remained enamoured of London until his death. ‘London streets and faces cheer me inexpressibly,’ he wrote to Wordsworth in 1833, ‘though of the latter not one known one were remaining’.9

The population of London in 1801 was already one million. By 1840 it had doubled in size, and by 1900 had exploded to six and a half million. As Wordsworth had found, the sheer size of London’s populace prevented connection between one man and his neighbour, at least in a traditional rural or small-town sense. An attitude of reserve and indifference was characteristic of the urban experience, the sociologist Georg Simmel noted in his essay ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’ (1903), as social contacts were too numerous and too fleeting to enable the extended interaction and trust developed in small-town communities. The social conditions of the modern city, Simmel believed, resulted in the evolution of a certain kind of urban mentality, better able to respond to the speed and diversity of urban life. ‘The psychological basis of the metropolitan type of individuality consists in the intensification of nervous stimulation which results from the swift and uninterrupted change of outer and inner stimuli,’ he argued, ‘the rapid crowding of changing images, the sharp discontinuity in the grasp of a single glance, and the unexpectedness of onrushing impressions’.10 The metropolitan mind, Simmel argued, is characterised by ‘a heightened awareness’, attuned to the range of stimuli it needs to process. ‘With each crossing of the street, with the tempo and multiplicity of economic, occupational and social life, the city sets up a deep contrast with small town and rural life with reference to the sensory foundations of psychic life,’ he observes:

The metropolis exacts from man as a discriminating creature a different amount of consciousness than does rural life. Here the rhythm of life and sensory mental imagery flows more slowly, more habitually, and more evenly. Precisely in this connection the sophisticated character of metropolitan psychic life becomes understandable.11

It was exactly the rushing, crowding sensations of the city that Lamb could not get enough of, and that yet overwhelmed Wordsworth, their contrasting responses demonstrating the differing influence of the urban and rural scene on the creative sensibility. While, for Wordsworth, rural surroundings enabled a mental space for reflection and a poetry that ‘takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity’,12 for the burgeoning urban poet-artist, the fast pace of city life acted as an equally powerful and transformative force on the imagination.

Raymond Williams writes in his classic study The Country and the City (1973) that ‘the perception of the new qualities of the modern city was associated, from the beginning, with a man walking, as if alone, in its streets’.13 The significance of the urban observer within twentieth- and twenty-first-century thinking on the city and its representation owes much to the work of the German cultural theorist Walter Benjamin on the flâneur, his essays on Charles Baudelaire, and his large, unfinished study of Paris in the nineteenth century, the Arcades Project.14 The flâneur has become the iconic personification of the highly developed perceptive skills of the urban observer, a connoisseur of metropolitan life, skilled at folding himself anonymously into the city streets, and priding himself in his ability to delineate the different types that made up the seemingly faceless urban crowd. For many critics, he is also a marker of the social and gender dynamics of the urban environment, and a metaphor for the way in which the city is read and understood. Yet the artist-flâneur typically combines varying degrees of social interest in everyday city life with an increasingly subjective, impressionist fascination with metropolitan modernity.

In this essay I offer an outline of the urban aesthetic imagination as it developed from Lamb across the nineteenth and into the early twentieth centuries. Examining the urban sketch as it was developed between the 1830s and 1890s by the writers Charles Dickens, Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Symons, I explore the essential tension in the figure of the flâneur, between an attitude of detached, rationalising control over the urban landscape, and an often simultaneous desire to plunge into the randomness and variety of urban life. In the final section of the essay I challenge the assumption that walking and observing the city was a necessarily male privilege, arguing for the increasing presence by the turn of the century of a female urban observer or flâneuse.

Amateur vagrancy

Despite Benjamin’s claim that ‘Paris created the type of the flâneur’, the phenomenon of the leisured urban observer was never an exclusively Parisian figure.15 Lamb’s London was already providing the conditions conducive to the flâneur’s habit of aimless wandering and fascinated voyeurism, its own gaslit streets and shopping arcades predating those of Paris by some decades, and its crowd vastly outnumbering that of the French capital. Moreover, London had witnessed a tradition of urban reportage similar to that of the feuilleton, the regular column or review section in Paris newspapers devoted to light sketches of urban life with which Benjamin associated the professional flâneur, from the early eighteenth century, when Joseph Addison and Richard Steele founded The Spectator (1711–14). Aimed at an emerging middle class audience, and circulating to an estimated audience of sixty thousand via London’s public coffee houses, this daily periodical focused its attention on the culture and manners of urban life, as observed through the eyes of its narrator ‘Mr. Spectator’, a wealthy and educated man of the world with a passion for city life, frequenting London’s ‘most publick Places’, and admitting that ‘where-ever I see a Cluster of People, I always mix with them’.16 The persona of an expert guide to the social and intellectual life of the city that he assumes in the paper is yet one of a man who is both at one with and separate from the urban crowd. ‘I live in the World, rather as a Spectator of Mankind, than as one of the Species,’ he asserts in the introduction to the first issue, ‘I have acted in all the parts of my Life as a Looker-on.’17 The trope of the urban writer as a detached observer rather than an engaged participant in city life would become one of the defining features of the burgeoning genre of writing concerned with reading the metropolitan environment in the nineteenth century.

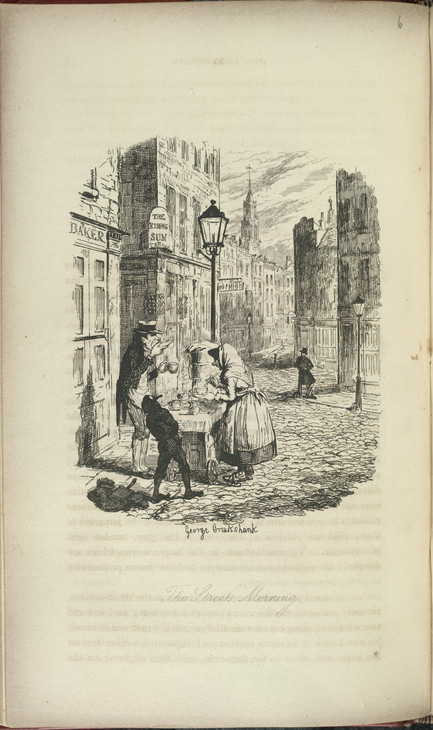

Archetypal examples of this new genre of imaginative urban reportage were Charles Dickens’s vignettes of London life, which he described as ‘street sketches’, published under the pseudonym ‘Boz’, to much popular acclaim in the Monthly Magazine and Morning and Evening Chronicle between 1833 and 1835, and revised and collected in Sketches by Boz (1836).18 Boz describes himself as a ‘speculative pedestrian’, intimately acquainted with the social and geographic map of early nineteenth-century London; from the City and Westminster at its centre, extending to the South bank, Limehouse and Whitechapel in the east, and the new suburbs of the ‘clerk population’, Camden, Pentonville and Islington, to the north. ‘We have an extraordinary partiality for lounging about the streets,’ he declares in an early version of ‘The Prisoners Van’, ‘Whenever we have an hour or two to spare, there is nothing we enjoy more than a little amateur vagrancy.’19

George Cruikshank 1792–1868

The Streets, Morning 1839 from 'Sketches by Boz'

British Library, London

Photo © British Library, London

Fig.1

George Cruikshank

The Streets, Morning 1839 from 'Sketches by Boz'

British Library, London

Photo © British Library, London

‘Amateur vagrancy’ seems to have been part of the lifeblood of Dickens the writer, who undertook long walks through the city almost every night. In a letter from Switzerland in August 1846, for example, he complained of the difficulty he found in trying to write when distanced from London’s vast crowd:

I suppose this is partly the effect ... of the absence of streets and numbers of figures. I can’t express how much I want these. It seems as if they supplied something to my brain, which it cannot bear, when busy, to lose. ... a day in London sets me up again and starts me. But the toil and labour of writing without that magic lantern is IMMENSE!! ... My figures seem disposed to stagnate without crowds about them.21

Rather like the persona of ‘Boz’, Dickens’s writing depends on the diverse stimuli of city life, and certainly his novels draw upon and develop the visual scenes and character portraits that typify his early newspaper sketches. One of the more insightful of early reviewers, Walter Bagehot, commenting on Dickens’s ‘marvellous power of observation’, wrote that in his books, ‘London is like a newspaper. Everything is there and everything is disconnected. There is every kind of person in some houses; but there is not more connection between the houses than between the lists of neighbours in the lists of “births, marriages, and deaths”.’22 Others were more critical of what they regarded as Dickens’s unrealistic portraits of human life. George Henry Lewes, for example, writing in the Fortnightly Review in 1872, complained that Dickens’s characters were not rounded identities but rather ‘personified characteristics; caricatures and distortions of human nature’, while George Eliot, although willing to admit that Dickens was ‘gifted with the utmost power of rendering the external traits of our town population’, similarly regretted that he seemed unable to render ‘their psychological character – their conceptions of life, and their emotions – with the same truth as their idiom and manners’.23

The eye of the flâneur is ultimately concerned with the external scene of the city, his skill the interpretation of the visual characteristics of the urban population, and this can lead to the representation of physiologies rather than individual human beings. Yet it is exactly through this focus on what Raymond Williams describes as the ‘hurrying seemingly random passing of men and women, each heard in some fixed phrase, seen in some fixed expression’, that Dickens’s sketches and novels capture the quality of experience of metropolitan life, and articulate the indifference of urban dwellers later identified by Simmel.24 As Boz observes at the start of his essay ‘Thoughts about People’:

’Tis strange with how little notice, good, bad or indifferent, a man may live or die in London. He awakens no sympathy in the breast of any single person; his existence is a matter of interest to no one save himself.25

In his urban scenes and caricatures Dickens captured the visual preoccupation of the metropolitan imagination and, as Williams argues, created a new mode of urban writing, ‘a way of seeing men and women that belongs to the street’.26

The man of the crowd

In June 1836 Sketches by Boz was reviewed by Edgar Allan Poe.27 Poe’s subsequent short story, ‘The Man of the Crowd’ (1840), owes much to Dickens not only in its setting (central London at dusk and evening), but also in the narrative device of the fascinated yet detached urban observer, hypersensitive to the identifiable features of the different groups that make up the urban crowd, and the development of a genre of urban writing that explores ways of reading the city. Poe, however, foregrounds the atmosphere of the uncanny that largely remains an undertone in Dickens’s quasi-realist depiction of the London scene.

Poe’s anonymous narrator has been convalescing in London after a lengthy illness, and begins his tale at the end of an afternoon that he has spent reading and people-watching from the window seat of a coffee house near Piccadilly. Peter Cunningham’s Hand-Book of London for 1850, which included a section on ‘COFFEE, &c., IN LONDON’, noted that at the best establishments the price of one shilling entitled the customer to ‘a cup of coffee and cigar, and the privileges of the room, the newspapers, chess, &c’.28 The narrator can thus be assumed to be enjoying a comfortable afternoon, in a leisured, male environment. His mindset as he surveys the scene both inside and out, is yet not one of simple idle curiosity, but rather of a heightened alertness and keen attention to surrounding life. ‘I felt a calm but inquisitive interest in every thing,’ he comments:

With a cigar in my mouth and a newspaper in my lap, I had been amusing myself for the greater part of the afternoon, now in poring over advertisements, now in observing the promiscuous company in the room, and now in peering through the smoky panes into the street.29

The coffeehouse is located on ‘one of the principal thoroughfares of the city’, and as it is now dusk, the time of day when the city is at its busiest, the narrator’s attention is soon entirely turned towards ‘the tumultuous sea of human heads’ that hurry past.30 At first, he admits, his observation ‘took an abstract and generalizing turn’, but he quickly becomes absorbed in a more detailed study of the passers-by, ‘regard[ing] with minute interest the innumerable varieties of figure, dress, air, gait, visage, and expression of countenance’.31 Through a process of astute observation and popular physiology, he demonstrates a remarkable ability to deduce the differing social groups and class levels of metropolitan life, remarking the ‘noblemen’, merchants and lawyers, the ‘tribe of clerks’, gamblers, pickpockets, street pedlars, beggars, seamstresses, ‘women of the town’, drunkards and more in a Boz-like taxonomy of early nineteenth-century London.

Yet despite the narrator’s extraordinary powers of observation, the city ultimately refuses his pretension to an encyclopaedic knowledge of the urban crowd, as suggested by the German saying with which the story opens: ‘er lasst sich nicht lessen’ (it does not permit itself to be read). For as the evening continues, there appears an old man whose strange appearance and fiendish expression even the narrator’s analytic observational skills fail to place. The man is thin and his clothes ‘filthy and ragged’, although of good cut and texture. Through a tear in his cloak, the narrator catches sight of a diamond and a dagger. Filled with an obsessive curiosity by this enigmatic figure, the narrator follows the old man as he weaves his way through the city streets, noting the way in which his movements become hesitant and increasingly frantic and erratic in relatively quiet or deserted areas, but steadier and more purposeful once immersed within large groups of people. Together they move through the streets, the narrator compulsively stalking his eccentric prey through the fog of the London night, until they come face to face at daybreak outside the original coffee-shop where the narrator’s increasingly wild chase had begun hours before. It is only now that the narrator is able to apply a category to this man, one defined by his very elusiveness, and the implicit threat of his ability to confound surveillance. ‘The old man is the type and the genius of deep crime,’ the narrator declares, ‘He refuses to be alone. He is the man of the crowd.’32

Constantin Guys 1802–1892

Carriages and Promenaders on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées

Watercolour on paper

Musée Carnavalet, Paris

Photo © Musée de la Ville de Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, France/ Giraudon/ The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.2

Constantin Guys

Carriages and Promenaders on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées

Musée Carnavalet, Paris

Photo © Musée de la Ville de Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, France/ Giraudon/ The Bridgeman Art Library

If Baudelaire here associates the modern artist’s fascinated perception of urban life with the keen appreciation of Poe’s convalescent narrator, he also seems to identify his desire for mingling with the multitude with that of the mysterious ‘man of the crowd’. Indeed, Baudelaire’s apparent collapsing of the principal characters in Poe’s story highlights their implicit identity as strange doubles of each other; the old man addicted to being within the crowd, and the narrator, feverishly exhilarated by the stimuli of the world around him and himself soon plunging into the busy streets. For far from seeking to remain separate from the crowd, Baudelaire’s modern artist desires to lose himself within it. ‘The crowd is his element’, he writes. Baudelaire’s urban artist is not a detached observer, objectively and authoritatively categorising the scene around him with a dispassionate eye. Rather, ‘His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite.’35 What Baudelaire articulates in his account of the modern artist who at once desires to be surrounded by the crowd and ‘rejoices in his incognito’, his ability ‘to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world’, is that it is exactly when one is amidst the crowd that one experiences a truly subjective solitude.36

City aspects

Baudelaire’s artist-flâneur, in his fascination with the transience and contingency of modernity, adds a new dimension to the urban observer, one predicated on aesthetic impressions rather than social phenomena. This focus on the aesthetic qualities of ‘the fugitive, fleeting beauty of present-day life’, begun with Lamb and Poe, returned to the London scene through the chief conduits of nineteenth-century French art and thought in Britain, Arthur Symons and Walter Sickert.37 Sickert’s apprenticeship with James Abbott McNeill Whistler, his friendship with Edgar Degas, and his own Degas-inspired pictures of London’s music halls as spaces of modern everyday life made him the principal advocate of impressionism in British art in the 1890s. Yet his definition of impressionism is far more evocative of the subjective imagination of Poe and Baudelaire than of simply the representation of the social scenes of modern urban life. ‘Essentially and firstly it is not realism’, he wrote in his introduction to the catalogue for the London Impressionists exhibition held at the Goupil Gallery in 1889:

It has no wish to record anything merely because it exists ... It accepts, as the aim of the picture, what Edgar Allan Poe asserts to be the sole legitimate province of the poem, beauty ... It is ... strong in the belief that for those who live in the most wonderful and complex city in the world, the most fruitful course of study lies in a persistent effort to render the magic and the poetry which they daily see around them.38

Symons too found in Poe and Baudelaire the origins of an impressionist and symbolist method that he would define as the central aesthetic principle of a ‘decadent movement’ in literature; a search for la vérité vraie, ‘the truth of appearances to the senses, of the visible world to the eyes that see it; and the truth of spiritual things to the spiritual vision’.39 The poetry of impressionism, he writes, ‘is the poetry of sensation, of evocation; poetry which paints as well as sings, and which paints as Whistler paints, seeming to think the colours and outlines upon the canvas, to think them only, and they are there’.40 ‘To fix the last fine shade,’ he continues, ‘the quintessence of things; to fix it fleetingly; to be a disembodied voice, and yet the voice of a human soul: that is the ideal of Decadence.’41 However, no English poet, he complained, had done for London what Baudelaire and other French poets had done for Paris; rendered the magic and poetry of modern life, and made the city ‘vital, a part of themselves, a form of creative literature’.42

Identifying himself with both Lamb and Baudelaire, Symons was an avid flâneur, recalling in London: A Book of Aspects (1909) that ‘London was for a long time my supreme sensation, and to roam in the streets, especially after the lamps were lighted, my chief pleasure’.43 ‘I don’t know whether you have heard of our wanderings by night, our studies of the ins and outs of London’, he wrote to a female friend, Katherine Willard, in 1891:

I have no interest in what is proper, regular, conventionally virtuous. I am attracted by everything that is unusual, Bohemian, eccentric: I like to go to queer places, to know strange people. And I like contrast, variety.44

The poetic sketches of the London scene that resulted from these walks, collected in Silhouettes (1892) and London Nights (1895), bear the influence of both the subject matter and style of the French poet in their concentration on the sensory and impressionist aspects of the city, and their evocation of the symbolic and often erotic quality of the fleeting moment. It is the artifice of the city that provides Symons’s muse, from the effects of gas-lamps on a wet pavement, accentuating ‘The magic and mystery that are night’s’, to the titillation of the painted faces of actresses and young dancers, ‘The charm of rouge on fragile cheeks’, and the potential promise in the glance and smile of a woman passed in the street.45 ‘Your fleeting Leonardo face, / Parisian Mona Lisa, dreams / Elusively’, he writes of the young woman observed ‘In an Omnibus’, questioning whether it is simply thoughts of fashion or something else, some invitation perhaps, that causes the ‘faint and fluctuating glint’ in her eyes.46

By the first decade of the twentieth century, however, Symons was bemoaning the increased mechanisation and materialism of the city, and the loss of the leisured and gendered privileges of the traditional flâneur. ‘What a huge futility it all seems, this human ant-heap, this crawling and hurrying and sweating and building and bearing burdens’, he observes in London: A Book of Aspects, with a sentiment closer to that of Wordsworth than Lamb, ‘After the fields and the sky London seems trivial, a thing artificially made, in which people work at senseless toils, for idle and imaginary ends’:

Charles Lamb could not live in this mechanical city, out of which everything old and human has been driven by wheels and hammers and the fluids of noise and speed. When will his affectionate phrase, ‘the sweet security of streets,’ ever be used again of London? No one will take a walk down Fleet Street any more, no one will shed tears of joy in the ‘motley Strand,’ no one will be leisurable any more, or turn over old books at a stall, or talk with friends at the street corner.47

Ernest Dudley Heath 1867–1945

Piccadilly Circus at Night 1893

Oil paint on canvas

Museum of London

© Museum of London and the Heath Family

Photo © Museum of London

Fig.3

Ernest Dudley Heath

Piccadilly Circus at Night 1893

Museum of London

© Museum of London and the Heath Family

Photo © Museum of London

The loss of the streets is a frequent lament within urban writing across the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries. Perhaps what Symons most regrets, however, is the loss of the fleeting erotic encounter that the city could promise the (always) male flâneur, that potential invitation in the passing glance from a woman on the street (fig.3). A few decades before, ‘[e]very morning promised an adventure; something or someone might be waiting at the corner of the next street’, he notes, but ‘the roads are too noisy now for any charm of expression to be seen on the pavement. The women are shouting to each other, straining their ears to hear. They want to get their shopping done and to get into a motor-car.’50 As we will go on to consider in the latter part of this essay, the female streetwalker was an increasingly independent woman, as much an urban observer and consumer in her own right as a spectacle for the gaze of the leisured male onlooker.

Busy traffic in central London, including motor cars, buses and pedestrians passing by the Shaftesbury Memorial in its original position in the middle of Piccadilly Circus 1911

© British Pathé

Perhaps because ‘it is only in a machine that you can escape the machines’, Symons states that he now sees London best from the top of an omnibus, when ‘coming in from the Marble Arch, that long line of Oxford Street seems a surprising and delightful thing, full of picturesque irregularities, and Piccadilly Circus seems incredibly alive and central’.51 The period of temporary respite from the noise and speed of the twentieth-century city seems to reinvigorate his sensory capacity for stimulation, and he finds himself as keenly aware of the impressions of the urban scene as Baudelaire’s artist of modern life. Consider, for example, his description of Piccadilly at dusk:

The Circus is like a whirlpool, streams pour steadily outward from the centre, where the fountain stands for a symbol. The lights glitter outside theatres and music-halls and restaurants; lights coruscate, flash from the walls, dart from the vehicles; a dark tangle of roofs and horses knots itself together and swiftly separates at every moment; all the pavements are aswarm with people hurrying.52

As the evening draws in, moreover, and the theatres and restaurants start to close their doors, the gendered dichotomy of urban space is reasserted: ‘In half an hour all this outflow will have subsided, and then one distinguishes the slow and melancholy walk of women and men, as if on some kind of penitential duty, round and round the Circus and along Piccadilly’, Symons observes with voyeuristic fascination:

the steady procession coils backward and forward, thickening and slackening as it rounds the Circus, where innocent people wait uncomfortably for omnibuses, standing close to the edge of the pavement. Men stand watchfully at all the corners, with their backs to the road; you hear piping voices, shrill laughter; you observe that all the women’s eyes are turned sideways, never straight in front of them; and that they seem often to hesitate, as if they were not sure of the way, though they have walked in that procession night after night, and know every stone of the pavement and every moulding on the brass rims of the shop-windows.53

Symons is no social commentator, however, and his aesthetic gaze differs from both that of the more sympathetic social eye of ‘Boz’, and the social-scientific observations of Poe’s narrator. The former, for example, in no doubt of the social status of the woman in ‘The Pawnbroker’s Shop’, ‘whose attire, miserably poor but extremely gaudy ... too plainly bespeaks her station in life’, notes in her fixed smile ‘a wretched mockery of the misery of the heart’, and observes with pity the shy young girl who is being pressed by her mother to give up a gold chain and ring, asking himself, ‘Who shall say how soon these women may change places?’54 The latter remarks upon the different categories to be observed among ‘women of the town of all kinds and of all ages’:

the unequivocal beauty in the prime of her womanhood, putting one in mind of the statue in Lucian, with the surface of Parthian marble, and the interior filled with filth – the loathsome and utterly lost leper in rags – the wrinkled, bejewelled, and paint-begrimed beldame, making a last effort at youth – the mere child of immature form, yet, from long association, an adept in the dreadful coquetries of her trade, and burning with a rabid ambition to be ranked the equal of her elders in vice.55

Symons’s concern, by contrast, is not with the instability of economic circumstance in the city, or the wretchedness or alienation of the fallen woman, nor with the range of types of moral depravity that the prostitute can embody. The men and women he observes are not individuals, of whose emotions or existence he gains a momentary glimpse, and their purpose for loitering is never made explicit. Instead, he evokes the atmosphere of illicit sexuality that pervades the landscape of Piccadilly Circus at night, an impersonal nocturne or impressionist ‘aspect’ of the city’s secrets.

The flâneuse

Across the nineteenth century the archetypal urban observer has been, as Raymond Williams has noted, ‘a man walking, as if alone, in its streets’.56 To loiter anonymously within the city streets of the nineteenth-century metropolis was an all but exclusively male luxury. The existence of a female urban observer, or flâneuse, was anathema to the social and gender configurations of the nineteenth- and turn-of-the-century city. The term ‘streetwalker’ when applied to a man may denote the flâneur, but when applied to a woman it refers to the prostitute. The exclusion of the female observer from the city, of course, raises questions about the representation in both literature and art of the period. ‘The literature of modernity describes the experience of men’, the cultural theorist Janet Wolff writes. Respectable women could not pursue the same private freedom in public space as men enjoyed; they could not visit restaurants or coffee houses alone, wander the streets day or night, or loiter in street corners catching the glance of passersby. Any female equivalent of the flâneur, she argues, was thus ‘rendered impossible by the sexual divisions of the nineteenth century’.57 Art historian Griselda Pollock agrees that ‘there is no female equivalent of the quintessential masculine figure, the flâneur: there is not and could not be a female flâneuse’.58

Neither Wolff nor Pollock deny the existence of women in the streets of the metropolis; indeed, they note their significant presence among the working classes, as prostitutes, and, in London in 1888, murder victims. What they do emphasise is women’s lack of power as observers of the urban scene. Pollock notes, for example, that ‘[w]omen did not enjoy the freedom of incognito in the crowd’, and that ‘women do not look. They are positioned as the object of the flâneur’s gaze.’59 Yet as I have argued elsewhere, by the last decades of the nineteenth century women were increasingly claiming a legitimate place within the public spaces of the city as employees, journalists, shoppers and tourists, activities that frequently brought them into the position of leisured observation of the city streets. Sidney Starr’s The City Atlas 1889 (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa),60 for example, one of the paintings exhibited at the London Impressionists exhibition at the Goupil Gallery, depicts a young, unchaperoned, yet respectably dressed young woman, travelling through a busy London suburban street on the top of an omnibus. She has possibly been shopping as she carries a large bunch of flowers, and the time of day is probably early evening, judging by the sunset in the distance and the lamps that are beginning to illuminate the street and the other vehicles. The perspective of the painting is an unusual one, moreover, with the viewer positioned behind the woman and thus observing the back of her head as she looks down the street in front of her. The woman in Starr’s picture is not positioned as an object for the gaze of male observers (indeed, her seat on the top of the omnibus places her in a position of authority above the shadowy male figure who can be glimpsed standing on the pavement just above her right shoulder), but rather as an urban observer in her own right. Starr’s painting provides both visual documentation and a useful metaphor for the presence of the female urban observer in London in the 1890s and 1900s.

By the 1900s it is possible to witness a female equivalent, and in some cases indeed deliberate rewriting, of the nineteenth-century tradition of the masculine urban observer.61 One amusing example of this conscious reshaping of what was by now a canonically male-authored urbanism is Baroness Orczy’s ‘Old Man in the Corner’ detective stories, which appeared between 1901 and 1904 in the Royal Magazine. Here the all-male coffee house of Poe’s ‘The Man of the Crowd’ is substituted for an ABC teashop, one of two chains of self-service eateries pioneered by the Aerated Bread Company and Lyons and Co., and in the 1890s a prominent feature of the central London landscape, serving a varied clientele from lower middle class workers to wealthier shoppers and tourists. Orczy’s tea shop is located on the Strand and frequented by a young ‘Lady Journalist’, finally named in the collected edition as ‘Miss Polly Burton’. Introduced in the opening tale, ‘The Fenchurch Street Mystery’, Polly is a financially independent ‘New Woman’, who likes to take her lunch while reading the daily newspaper and watching the people who pass on the street:

Now this particular corner, this very same table, that special view of the magnificent marble hall – known as the Norfolk Street branch of the Aërated Bread Company’s depôts – were Polly’s own corner, table, and view. Here she had partaken of eleven pennyworth of luncheon and one pennyworth of daily information ever since that glorious never-to-be-forgotten day when she was enrolled on the staff of the Evening Observer (we’ll call it that, if you please), and became a member of that illustrious and world-famed organization known as the British Press.62

Like the narrator of Poe’s ‘Man of the Crowd’, she is interrupted from her reading of the Daily Telegraph (where she is engrossed in the latest crime reports) by a thin, strangely dressed, fidgety old man who visits the teashop for milk and cheesecake, and proceeds to regale her with the solution to a famous unsolved crime, before disappearing suddenly into the street, only to return the next day to unravel another mystery. Alternating between arrogant sarcasm at Polly’s obtuseness, and fevered excitement at his own supreme powers of deduction, all the time he compulsively knots and unknots a piece of string. At once irritated and fascinated by this mysterious stranger, Polly finds herself drawn back again and again to the restaurant, an eager student of his process of shrewd observation and deductive reasoning. Unlike Poe’s hyper-observant narrator, however, for all her fascination with crime stories, Polly has not herself developed powers of immediate observation, as the old man explains to his protégée when she fails to recall the appearance of a man who had been sat next to her earlier in the day:

you are a journalist – call yourself one, at least – and it should be part of your business to notice and describe people ... the average Englishman, say, of the middle classes, who is neither very tall nor very short, who wears a moustache which is neither fair nor dark, but which masks his mouth, and a top hat which hides the shape of his head and brow, a man, in fact, who dresses like hundreds of his fellow-creatures, moves like them, speaks like them, has no peculiarity.63

Polly, however, is a quick student, and it does not take her long to realise that the criminal in the final case of the collection, whom he excitedly describes as ‘one of the most ingenious men of the age’, and whose defining feature is that he leaves behind him a piece of string tied with knots, is in fact the old man himself. Orczy’s man in the corner is a knowing recreation of Poe’s ‘man of the crowd’, ‘the type and the genius of deep crime’.64 For Poe’s leisured male protagonist and quasi-detective, however, she substitutes a perceptive young female journalist.

Perhaps one of the most extended articulations of the figure of the flâneuse in the tradition of the impressionist urban observer, however, is to be found in Dorothy Richardson’s thirteen-volume novel Pilgrimage (1915–67), a semi-fictionalised autobiographical account of her own life in London two decades before, first during a brief period in 1892 as a teacher at a small school in the newly built northern suburb of Finsbury Park, and then from 1896 as a dental secretary, living in a boardinghouse in Bloomsbury.65 Walking in London was as much a necessity for Richardson as it had been for Lamb, Dickens and Symons, both to and from work during the day, but also a more leisured roaming of the city at night. ‘Soon after sunset a message would reach even the most stifling attic’, she later recalled, ‘brought by the evening air stealing in at its open window’; she would swap the solitude of her small room for the companionship of the Bloomsbury squares, where ‘giant trees mingled their breath with mine, their being with my own’.66 The impoverished yet entrancing London years form the landscape of the middle volumes of Pilgrimage, odes to the city written in continuous interior monologue, in which the bond between the autobiographical protagonist Miriam Henderson and the city streets persists beyond the otherwise brief acquaintances or transient friendships of her urban life.67

For the purposes of this essay, and for comparison with Symons’s contemporaneous recollection of walking in London in the 1890s, I want to explore two lengthy journeys that Miriam makes through the city, the first on the top of an omnibus following her interview for the teaching post in Banbury Park (Richardson’s fictionalised version of Finsbury Park), a journey which takes her from north London, down the length of Seven Sisters and Camden Roads until she eventually reaches Euston Road, Regent Street and Piccadilly, where the bus then turns along Hyde Park on its way to the family home in Putney, and the second a circuitous walk that she takes late at night through Bond Street, Piccadilly Circus and Shaftesbury Avenue to Bloomsbury. Both scenes, the first over ten pages in length, the second near to fifty, present Miriam as a hyper-sensitive impressionist observer of the London landscape, extraordinarily attune to the subjective effects of different streets and areas. While the younger Miriam responds most directly to the social scene surrounding her, however, the later walk demonstrates an aesthetic perspective alive to the magic and poetry of the city.

The omnibus journey takes place in the second book of Pilgrimage, ‘Backwater’ (1916), when Miriam is only eighteen. Finsbury Park was a new suburb in the early 1890s, and the terminus of the tram line. ‘They would soon be down at the corner of Banbury Park where the tram lines ended and the Favourite omnibuses were standing in the muddy road under the shadow of the railway bridge’, Richardson writes, as Miriam and her mother make their way to the bus depot for their journey home; Miriam, like Starr’s young woman, climbs eagerly to the front seat on the top, exclaiming: ‘This is the only place on the top of a bus.’68 Her excitement is soon muted by the monotony of the north London landscape:

They lumbered at last round a corner and out into a wide thoroughfare, drawing up outside a newly-built public-house. Above it rose row upon row of upper windows sunk in masses of ornamental terra-cotta-coloured plaster. Branch roads, laid with tram-lines led off in every direction. Miriam’s eyes followed a dull blue tram with a grubby white-painted seatless roof jingling busily off up a roadway where short trees stood all the way along in the small dim gardens of little grey houses ... The little shock sent her mind feeling out along the road they had just left. She considered its unbroken length, its shops, its treelessness. The wide thoroughfare, up which they now began to rumble, repeated it on a larger scale. The pavements were wide causeways reached from the roadway by stone steps, three deep. The people passing along them were unlike any she knew. There were no ladies, no gentleman, no girls or young men such as she knew. They were all alike. They were ... She could find no word for the strange impression they made. It coloured the whole of the district through which they had come.69

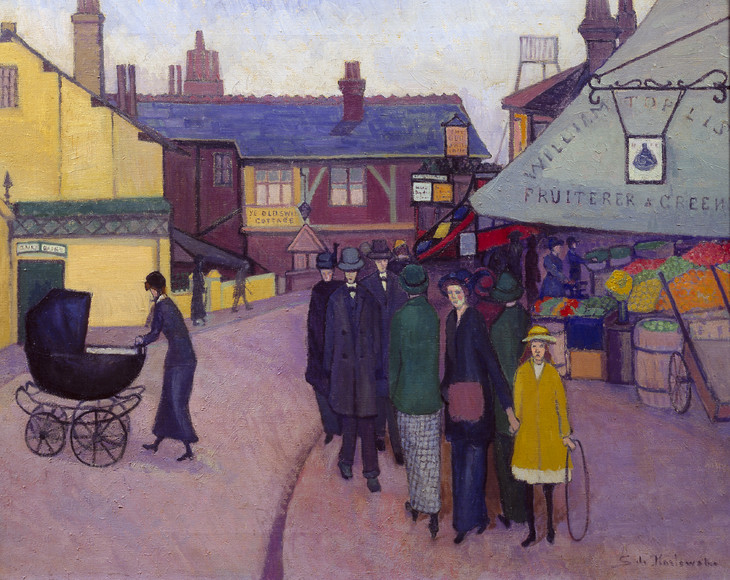

Stanislawa De Karlowska 1876–1952

Swiss Cottage exhibited 1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 762 mm; frame: 788 x 940 x 90 mm

Tate N06239

Presented by the artist's family 1954

© Tate

Fig.4

Stanislawa De Karlowska

Swiss Cottage exhibited 1914

Tate N06239

© Tate

This new secret was shabby, ugly and shabby. The half-perceived something persisted unchanged when the causeways and shops disappeared and long rows of houses streamed by, their close ranks broken only by an occasional cross-road. They were large, high, flat-fronted houses with flights of grey stone steps leading to their porchless doors. They had tiny railed-in front gardens crowded with shrubs. Here and there long narrow strips of garden pushed a row of houses back from the roadway. In these longer plots stood signboards and show-cases. ‘Photographic Studio,’ ‘Commercial College,’ ‘Eye Treatment,’ ‘Academy of Dancing.’ ... She read the announcements with growing disquietude.70

Finally they reach the intersection with Euston Road, which Richardson would always identify as the boundary between London proper and the quiet horror of the suburbs, and the atmosphere of dull oppression lifts, the omnibus now moving through wide streets and balconied houses. Immediately the preoccupation with the social scene subsides, and Miriam’s perceptions focus on the impressionist beauty of the city light, in a description that recalls the vista enjoyed by the young woman of Starr’s painting: ‘The side-streets were feathered with trees and ended mistily ... At the end of the vista the air was like pure saffron-tinted mother-of-pearl. Miriam sat back and drew a deep breath.’71 Like a true flâneur she is invigorated once she is within the bustling, public world of Regent Street and Piccadilly, and excitedly describes the view to her mother in terms that reveal her easy assumption of the role of urban consumer: ‘You’ll see our A B C soon. You know. The one we come to after the Saturday pops ... It’s just round here in Piccadilly. Here it is. Glorious ... We go along the Burlington Arcade too ... It’s simply perfect. Glove shops and fans and a smell of the most exquisite scent everywhere.’72

By the time of the second scene, from the seventh Pilgrimage book, ‘Revolving Lights’ (1923), Miriam has been working and living permanently in London for several years. Leaving a Fabian Society meeting late at night, she welcomes the London pavements that ‘offered themselves freely; the unfailing magic that would give its life to the swing of her long walk home’.73 Absorbed in her own musings she takes a winding route back to Bloomsbury, a flâneuse strolling through the relatively silent city streets, enjoying what she describes as a ‘plebeian dilettantism’.74 Of course, the flâneur’s vision is an essentially moving one, and as she walks the streets and buildings around her ebb and flow, her mind, as Baudelaire had described that of the artist-flâneur a ‘kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness’:

solid lines and arches of pure grey shaping the flow of the pageant, and emerging, then it ebbed away, to stand in their own beauty, conjuring back the vivid tumult to flow in silence, a continuous ghostly garland of moving shapes and colours.75

Highly sensitive to the effect of different streets and places on her perceptions and psyche, she instinctively eschews the more populated and brash modern thoroughfare of Oxford Street for the relative quiet of its surrounding streets:

Oxford Street opened ahead, right and left, a wide empty yellow-lit corridor of large shuttered shop-fronts. It stared indifferently at her outlined fate ... Oxford Street, unless she were sailing through it perched in sunlight on the top of an omnibus lumbering steadily towards the graven stone of the City, always wrought destruction ... Stay here, suggested Bond Street.76

Miriam is no ‘woman of the crowd’, eager to lose herself within its mass, and remains socially detached and fiercely protective of her independence throughout the Pilgrimage novels, embracing the solitude that Simmel identified as so characteristic of metropolitan life:

her untouched self here, free, unseen, and strong, the strong world of London all round her, strong free untouched people, in a dark lit wilderness, happy and miserable in their own way, going about the streets looking at nothing, thinking about no special person or thing, as long as they were there, being in London.77

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 813 x 660 mm; frame: 939 x 786 x 65 mm

Tate T03096

Purchased 1980

© The estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.5

Charles Ginner

Piccadilly Circus 1912

Tate T03096

© The estate of Charles Ginner

‘I am always charmed to read beautiful poems about nature in the country. Only, personally, I prefer town to country’, Symons wrote in the preface to Silhouettes, echoing the sentiments of Lamb with which I began this essay, ‘and in the town we have to find for ourselves, as best we may, the décor which is the town equivalent of the great natural décor of fields and hills’.80 ‘If anyone sees no beauty in the effects of artificial light, in all the variable, most human, and yet most factitious town landscape,’ he continued, ‘then I can only pity him, and go on my own way’.81 From Lamb through to Dickens, Poe, Baudelaire, Symons and Richardson, the tradition of the urban observer that I have traced through this essay is that of Baudelaire’s ‘perfect flâneur’, the passionate spectator and artist of ideal modern life, focused upon the rendering of the impressions and sensations of urban experience rather than moral or narrative interest, and alive, as Symons wrote of Lamb in a statement that recalls Simmel’s definition of the metropolitan mind, to ‘the simultaneous attack and appeal of contraries, a converging multitude of dreams, memories, thoughts, sensations, without mental preference, or conscious guiding of the preference’.82

Notes

Charles Lamb, letter to William Wordsworth, 30 January 1801, in Alfred Ainger (ed.), The Letters of Charles Lamb, vol.1, Macmillan & Co., London 1888, pp.164–5.

Arthur Symons, ‘Charles Lamb’, Living Age, vol.30, 1906, reprinted in Arthur Symons, Figures of Several Centuries, Constable, London 1916, p.22.

William Wordsworth, ‘Lines Composed Upon Westminster Bridge’, in The Complete Poetical Works, Macmillan and Co., London 1888, http://bartleby.com/ .

Georg Simmel, ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’, in Malcom Miles, Tim Hall, Iain Borden (eds.), The City Cultures Reader, Routledge, London 2000, p.13.

William Wordsworth, ‘Preface to Lyrical Ballads’, in M.H. Abrams (ed.), The Norton Anthology of English Literature, sixth edn, vol.2, W.W. Norton & Company, New York 1993, p.151.

Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism, trans. by Harry Zohn, Verso, London 1983, and The Arcades Project, Rolf Tiedemann (ed.), Harvard University Press, Harvard 1999.

Madeleine House and Graham Storey (eds.), The Letters of Charles Dickens: 1820–1839, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1965, p.55.

Quoted in Dennis Walder, ‘Introduction’, in Charles Dickens, Sketches by Boz, Penguin, London 1995, p.xxi.

Walter Bagehot, ‘Charles Dickens’, National Review, October 1858, pp.458–86, in Philip Collins (ed.), Dickens: The Critical Heritage, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1971, pp.403–11, p.406.

George Eliot, ‘The Natural History of German Life’, Westminster Review, July 1856, p.lxvi, in Collins (ed.) 1971, p.355.

Reprinted in G.R. Thompson(ed.), Edgar Allan Poe: Essays and Reviews, Library of America, New York 1984, pp.104–7.

Edgar Allan Poe, ‘The Man of the Crowd’, in Tales of Mystery and Imagination, Wordsworth, Hertfordshire 1993, p.255.

Charles Baudelaire, ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, in Charles Harrison, Paul Wood and Jason Gaiger (eds.), Art in Theory, 1815–1900, Blackwell, Oxford 1998, p.495.

Walter Sickert, ‘Impressionism’, in A Collection of Paintings by the London Impressionists, exhibition catalogue, Goupil Gallery, London 1889, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.60.

Arthur Symons, ‘The Decadent Movement in Literature’ (1893), reprinted in Arthur Symons, Dramatis Personae, Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis 1923, p.99.

Arthur Symons, letter to Katherine Willard, 20 May 1891, in Karl Beckson and John M. Munrow (ed.) Arthur Symons: Selected Letters, 1880–1935¿, University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 1989, p.79.

Arthur Symons, ‘Nocturne’, Silhouettes, second edn, Leonard Smithers, London 1896, p.63; Arthur Symons, ‘Maquillage’, ibid., p.14.

Janet Woolf, ‘The Invisible Flâneuse: Women and the Literature of Modernity’, Theory, Culture and Society, vol.2, no.3, 1985, p.45.

Griselda Pollock, ‘Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity’, Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art, Routledge, London 1988, p.71.

Reproduced in Degas, Sickert and Toulouse-Lautrec: London and Paris 1870–1910, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2005 (24).

The first eleven books of Pilgrimage were published separately: Pointed Roofs (1915), Backwater (1916), Honeycomb (1917), The Tunnel (February 1919), Interim (December 1919; also serialised in the Little Review, June 1919–May 1920), Deadlock (1921), Revolving Lights (1923), The Trap (1925), Oberland (1927), Dawn’s Left Hand (1931), Clear Horizon (1935). The twelfth, Dimple Hill, was added to the four-volume collected edition Pilgrimage, Dent, London and Knopf, New York 1938. A thirteenth, March Moonlight, which Richardson had been working on up to her death, appeared in the revised edition published by Dent in 1967.

See Dorothy Richardson, ‘The Tunnel’, ‘Interim’, ‘Deadlock’ and ‘Revolving Lights’, in Dorothy Richardson, Pilgrimage, Gillian Hanscombe (ed.), vols.2 and 4, Virago, London 1979.

Dorothy Richardson, ‘Backwater’, Pilgrimage, Gillian Hanscombe (ed.), vol.1, Virago, London 1979, pp.2, 192

Dorothy Richardson, ‘Revolving Lights’, Pilgrimage, Gillian Hanscombe (ed.), vol.3, Virago, London 1979, p.236.

Deborah Longworth is Senior Lecturer in the Department of English at the University of Birmingham.

How to cite

Deborah Longworth, ‘The Urban Observer’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www