When my sister Rebecca and I went to Bolton Landing we were not simply visiting our father, we were leaping into a magical world of formation and transformation. The sculpture Dida’s Circle on a Fungus 1961 came out of one such day when we took a walk in the woods to look for interesting discoveries. In this case the subject was wild mushrooms, huge things we called ‘tree ears’ – a fungus up to the size of a very large man’s hand, growing on the trees like an ear, positioned sideways. We took sticks and scraped the underside of the mushroom, leaving dark sepia lines. I drew a pattern suitable to be hidden in the forest. Apparently, one of these fungus ‘drawings’ was the impetus for the sculpture.

During these walks my father liked to tell stories about his ancestry, and they were always different. I think it pleased him to reinvent himself constantly. There was one about being descended from Native Americans, and all of us walked through the forest as if we were. His sculptures were, in many ways, a response to the outdoors. He even wrote that at one point he found himself using the colours of the garden, of crazy wildflowers. Dida’s Circle is also a kind of crazy wildflower.

We used to make art together in the drawing studio. Not welding, of course, because it wasn’t safe – we were too young – but wooden sculptures and lots of drawings and paintings with spray paint or oils.

He often said that, as he was an older father when we were born, he might not live to see us grow up, but he would write a greeting for me and Rebecca on his sculptures, so that they could greet us when we saw them. For example, if you look at Wagon II 1964, which belongs to Tate, he has inscribed ‘Hi Candida’ on one of the wheels. Whether the works were in a museum or at home, he could still speak to us, although he was no longer there. I thought that was a very friendly thing to do. He created a bond between himself, his art and his children. My curatorial work, the talks I give and the writing I have done are my ways of keeping faith with my father.

The smell of spray paint, grinding cold steel and the sizzle and spit of the welding torch are very cosy and comfortable to me – they are my version of the memory of the smell of chocolate-chip cookies in the oven. The wonder was that he let us into his unconscious in a way that very few children experience. There in his sculptures was his imagination, layered out in the fields at Bolton Landing: aspects of his identity, proclaiming their nature bold on the mountain top. He allowed us to climb the biggest, strongest sculptures and bang on them when we wanted to make music. I can still hear the sounds we made. It was the music of the fields.

Everything my father did was as an artist, so making art was not an activity, but rather the way he lived. The first thing he did every day when he got up at Bolton Landing was to look from the terrace to see the deer or foxes and the light on the sculptures.

We talked very easily. We would tell him what we liked or didn’t like, and whether painted pieces that evolved over time, such as Dida’s Circle, were improving or not. At the end of one summer, when we were going back to Washington, he asked if there was anything I wanted to take with me. I pointed to a big sculpture that I really loved. But we were living in the inner city and had no place for such a thing. However, about a month later a miniature of Three Planes 1961 arrived.

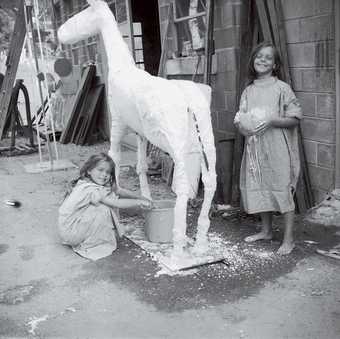

I remember Rebecca made him a horse picture cut out of lined paper. She had glued on the tail, the head and the two legs, some on one side of the paper and some on the other, and he was fascinated by her choices and shapes. He made a replica out of silver with a golden eye. We still own that piece. It was the basis for the magnificent Becca 1965, owned by the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

My father’s work influenced my own process of becoming a choreographer. After he was gone, in my early years, I would sit out in the fields among his sculptures and feel as if I was in his presence. I would sit and think about what was real and about loss, and about what was worth doing. In the end, I stood up and wanted to be a dancer. There was a very strong theatrical dance element to his sculptures in how they related to each other.

I grew up thinking abstract art was normal. It was years after my father died before I was able to figure out why anyone would make a painting that actually looked like something in the real world. It’s all a matter of where you begin. From my perspective, the level of ideation was so much more vivid and exciting and unencumbered. So I think I was looking to live my life in an abstract way, and dance is the perfect metaphysical activity. Dance takes abstraction further. It has no physical form. It comes from what the dancers do, what the lighting is, what the costumes are, the tempo, the sense of weight and space defined within the dance, but it has no objective reality. You can at no point say to me ‘that is the dance’. You can’t buy it, and you can’t sell it. Its reality is virtual, not physical.

The sculptures were the acts of my father’s days, my father’s will, his identity. The 78 or so works in the fields recorded his struggles, thoughts, humour, his personal Battle of Being. I ask myself if these sculptures were my siblings – they were born of my father and were companions of my childhood, were they not?